3.5 Applying the Nursing Process and the Clinical Judgment Model to Healthy Diets

This section will describe how a nurse uses the nursing process and the clinical judgment model to promote healthy diets. Stages of the National Council of State Board of Nursing (NCSBN) Clinical Judgment Model are indicated in parentheses.

Review information about the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Model in the “Applying the Nursing Process and the Clinical Judgment Model to Healthy Diets” chapter.

Assessment (Recognize Cues)

Subjective Assessment

A thorough assessment of a client’s dietary intake and preferences is the first step in developing a plan of care for clients. A nutritional assessment includes gathering information from the client through interviewing, reviewing lab and diagnostic results, and performing a physical examination.

Subjective assessments include questions regarding normal eating patterns and risk factor identification. Subjective assessment data is obtained by interviewing the client as a primary source or a family member or caregiver as a secondary source. While a wealth of subjective data can be obtained through a chart review, it is important to verify this information with either the client or family member because details may be recorded inaccurately or may have changed over time. Subjective information to obtain when completing a nutritional assessment includes age, sex, history of illness or chronic disease, surgeries, dietary intake including a 24-hour diet recall or food diary, food preferences, cultural practices related to diet, normal snack and meal timings, food allergies, special diets, and food shopping or preparation activities.[1]

A detailed nutritional assessment can also provide important clues for identification of risk factors for nutritional deficits or excesses. For example, a history of anorexia or bulimia will put the client at risk for vitamin, mineral, and electrolyte disturbances, as well as potential body image disturbances. Swallowing impairments place the client at risk for decreased intake that may be insufficient to meet metabolic demands. Use of recreational drugs or alcohol places the client at risk for insufficient nutrient intake and impaired nutrient absorption. Use of over-the-counter, unprescribed nutritional supplements places the client at risk for excess nutrient absorption. Recognizing and identifying risks to nutritional status help the nurse anticipate problems that may arise and identify complications as they occur. Information from these subjective assessments can be used, in conjunction with review of lab and diagnostic results and physical examination, to develop a plan of care for the client.[2]

Nutritional Assessment Tools

A variety of tools may be used to obtain information about a client’s food intake patterns. This subsection will provide an overview of common nutritional assessment tools.

24-hour Dietary Recall

A 24-hour dietary recall aims to provide detailed information about food and beverages consumed by a client in the past 24 hours. Clients are interviewed by either trained individuals or by completing an automated interviewing system that gathers information, including the types of foods or drinks consumed, time of consumption, preparation method, and portion size.

Food Record

A food record, also called a food diary, allows the client to record their intake in real-time over a specific period of time. Instructions are provided to the client as to how to use a designated form or record. The client should record all foods and beverages consumed, including type of food, brand names, preparation method, and portion size. Several food tracker apps are also available for download onto smart devices for clients who prefer to record their intake electronically. See Figure 3.10[3] for an image of a sample weekly food record.

Diet History Questionnaire

A diet history questionnaire is used to track consumption of specific foods or beverages over a period of time, such as the last week, month, or year. Use the information in the following box to view the National Cancer Institute’s examples of free, online diet history questionnaires.

View free, online diet history questionnaires from the National Cancer Institute: Diet History Questionnaire III (DHQ III) web page.

Mini Nutritional Assessment

The Nestle Nutritional Institute created a nutritional assessment for clients over the age of 65 called the mini nutritional assessment (MNA). The MNA uses information about food intake, weight loss, mobility, psychological stress, acute disease, neuropsychological problems, and body mass index to assess nutritional status. Based on scoring, clients are categorized as having normal nutritional status, at risk for malnutrition, or malnourished. Recommended interventions are outlined for providers based on the MNA score.

View the Mini Nutritional Assessment PDF from the Nestle Nutritional Institute.

Objective Assessment

Objective assessment data is information derived from direct observation by the nurse and is obtained through inspection, auscultation, and palpation. The nurse should consider nutritional status while performing a physical examination.[4]

The nurse begins the physical examination by making general observations about the client’s status. A well-nourished client has normal skin color and hair texture for their ethnicity, healthy nails, and appears energetic. The nurse also measures and documents the client’s height and weight.[5]

Body Mass Index

Height and weight in adults are often compared to a body mass index (BMI) graph. BMI can also be calculated using the following formulas[6]:

- BMI = weight (kilograms)/height(meters)2

- BMI = weight (pounds) x 703)/height(inches)2

To calculate BMI using a BMI table, the client’s height is plotted on the horizontal axis, and their weight is plotted on the vertical axis. The BMI is measured where the lines intersect. See Figure 3.11[7] for a BMI table for interpreting adult weights. BMI is interpreted using the following ranges[8]:

- Less than 18.5 kg/m2: Underweight

- 18.5-24.9 kg/m2: Desirable range

- 25-29.9 kg/m2: Overweight

- Equal or greater than 30 kg/m2: Obese

It is important for nurses to understand that although BMI is a helpful screening tool, it has limitations. It varies with age, sex, and ethnicity and does not differentiate between body fat and muscle mass, which can lead to misclassification. BMI should be used along with other assessments for an accurate evaluation of a person’s overall health.[9]

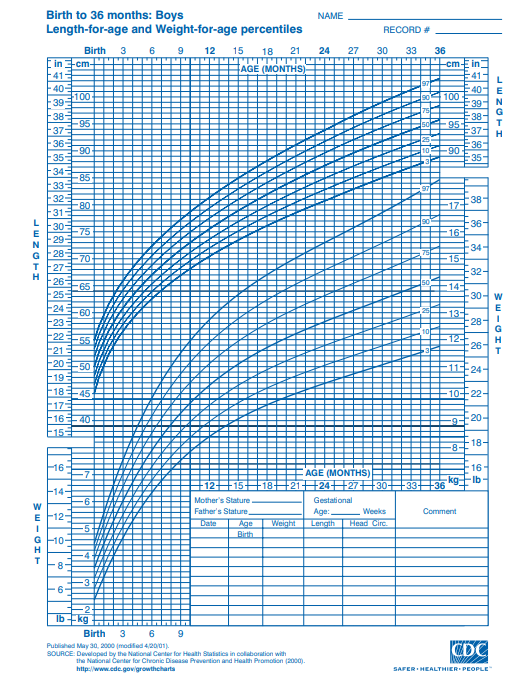

Pediatric Height, Weight, and Growth Charts

Growth charts can be used to monitor nutritional status in children. Height and weight for infants and children are plotted on a growth chart to give a percentile ranking across the United States population.[10]

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) recommends growth charts be used in conjunction with other assessments rather than as a sole measurement of health of a child. Consideration should be given to parental stature, chronic illness, or other special health care needs. The World Health Organization (WHO) charts are recommended for children from birth to two years, and the CDC growth charts are recommended for children from 2-19 years of age.[11] See Figure 3.12[12] for an example of a growth chart for boys from birth to 36 months.

Growth chart training is provided by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).[13] Use the information provided in the following box to view these instructions from the CDC. If growth is not proceeding as expected based on the growth charts, the client is referred for additional evaluation by health care providers.

View Growth Chart Training from the CDC.[14]

Accurate Pediatric Length and Weight Measurement

Accuracy is vital when measuring and documenting pediatric heights and weights. Three critical components for accurate pediatric measuring and weighing for use with the growth charts are technique, equipment, and trained measurers.[15]

When weighing an infant, the scales should be calibrated with precision of 0.01 kg or 1/2 ounce. Infants should be nude; wearing a clean, disposable diaper; and positioned in the center of the scale tray. The weight of the diaper is deducted, and the weight should be documented in grams or to the nearest or 1/2 oz. The infant should be repositioned in the scale, the weight measurement repeated, and the second weight noted in writing. The two weights should agree within 0.1 kg or 1/4 pound; if they don’t meet this standard, the infant should be repositioned and reweighed a third time. An alternative measurement technique may be used if an electronic scale is available. Have the parent stand on the scale, reset the scale to zero, and then have the parent hold the infant and read the infant’s weight. However, many adult scales generally only weigh to the nearest 100 gm.[16]

Length should be measured in the supine position for infants younger than 24 months of age or children aged 24 to 36 months who cannot stand unassisted. Accurate length measurement requires a calibrated length board with a fixed headpiece and a moveable, perpendicular foot piece. Shoes and hair ornaments should be removed. The child should be placed on their back in the center of the length board so that they are lying straight, and their shoulders and buttocks are flat against the measuring surface. The child’s eyes should be looking straight up so their chin is not tucked in against their chest or stretched too far back. Both legs should be fully extended, and the toes should be pointing upward with feet flat against the foot piece. Both legs should be fully extended for an accurate and reproducible length measurement. Correctly positioning the infant for a length measurement generally cannot be accomplished without two measurers. The length should be documented to the nearest 0.1 cm or 1/8 inch, and then the infant should be repositioned, and the length measurement repeated and documented. The length measurements should be compared and agree within 1 cm or 1/4 inch. If they don’t agree within this range, the infant should be repositioned and remeasured a third time.[17]

Common Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

Laboratory and diagnostic tests may be ordered by health care providers to assess a client’s nutritional status. Common lab tests ordered to assess nutritional status include hemoglobin (Hgb), hematocrit (HCT), white blood cells (WBC), albumin, prealbumin, and transferrin.[18] See Table 3.5a for a summary of nursing considerations related to these lab results.

Table 3.5a. Selected Laboratory Tests Related to Nutrition

| Lab | Normal Range | Nursing Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Hemoglobin (Hgb) | Females:

12 – 16 g/dL Males: |

Hemoglobin measures the oxygen-carrying capacity of blood. Decreased levels may occur due to hemorrhage or deficiencies in iron, folate, or B12.

10 – 14: Mild anemia 6 – 10: Moderate anemia Less than 6: Severe anemia |

| Hematocrit (Hct) | 37 – 50% | Hematocrit is normally three times the client’s hemoglobin level during normal fluid status. Increased levels can occur with dehydration or medical conditions, and decreased levels can occur with anemia, fluid overload, or hemorrhage. |

| White blood cells (WBC) | 5,000 – 10,000 mm3 | Increased levels occur due to infection. Decreased levels occur due to prolonged stress, poor nutrition, or deficiency of vitamin C, D, E, or B-complex intake.

Less than 4,000: At risk for infection or sepsis Greater than 11,000: Infection likely |

| Magnesium | 1.6 – 2.6 mEq/L | Decreased levels can occur with poor nutrition or alcohol misuse. Increased levels may occur due to kidney dysfunction.

Critical values can cause cardiac complications: <1.2 mg/dL or >4.9 mg/dL. |

| Potassium | 3.5-5 mmol/L | Increased levels may occur due to health conditions or side effects of medications. Decreased levels may occur due to side effects of medications or insufficient dietary intake of potassium.

Critically abnormal values can cause cardiac complications. |

| Albumin | 3.4 – 5.4 g/dL | Increased levels occur with dehydration. Decreased levels occur due to zinc deficiency, corticosteroid use, protein deficiency over several weeks, or conditions resulting in muscle wasting/muscle loss. |

| Prealbumin | 15 – 36 mg/dL | Increased levels occur due to corticosteroid or contraceptive use. Decreased levels may indicate malnutrition. |

| Transferrin | 250 – 450 mcg/dL | Increased levels may occur due to dehydration or iron deficiency. Decreased levels may occur due to anemia; vitamin B12, folate, or zinc deficiency; protein depletion; or conditions resulting in muscle wasting/muscle loss. |

| 24-hour urine creatinine | Males: 0.8 – 1.8 g/24 hrs

Females: 0.6 – 1.6 g/24 hrs |

Increased levels may occur with renal disease and muscle breakdown. Decreased levels may occur due to malnutrition with muscle atrophy. |

See “Appendix A” for reference ranges of other lab values. As always, refer to agency lab reference ranges when providing client care.

Review additional information about these labs in the “Applying the Nursing Process” section of the “Nutrition” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

Analyzing Data: Expected and Unexpected Findings

After completing the subjective and objective assessment, the nurse analyzes the data for expected and unexpected findings. See Table 3.5b for a comparison of expected versus unexpected assessment findings related to nutritional status.

Table 3.5b. Expected Versus Unexpected Findings in Body Systems Related to Nutritional Status[19]

| Assessment | Expected Findings | Unexpected Findings |

|---|---|---|

| General appearance | Energetic and weight proportional to height | Underweight or overweight; lethargic |

| Eyes | Vision clear and eyes moist | Dry eyes |

| Mouth | Moist mucous membranes, intact oral mucosa, and intact smooth tongue | Dry/sticky mucous membranes, oral ulcerations, glossitis (swollen tongue), coughing while swallowing, inability to swallow, or poor dentition |

| Extremities/Integumentary | Skin tone normal for ethnicity and warm, dry, and intact; hair full and shiny; and nails smooth and intact; skin turgor elastic and supple texture; strong muscles | Tenting (poor skin turgor), dry skin or eyes, mouth sores, bleeding gums, loss of night vision, hair loss, poor wound healing, pallor, muscle weakness, brittle nails, or lack of hair luster |

| Neurological | Sensation and cognition intact | Numbness or tingling, tetany, or acute confusion |

| Cardiac | Regular heart rhythm and rate between 60-100 in adults; capillary refill less than three seconds; pulses strong; normal EKG tracing | Bounding pulses, S3 heart sounds, jugular venous distention, or cardiac arrhythmias |

| Respiratory | Clear lung sounds throughout; regular respiratory rhythm, respiratory rate in adults 12 to 20 breaths per minute; unlabored breathing | Shortness of breath or respiratory distress |

| Gastrointestinal | Normal stool quality and frequency for client, bowel sounds present x 4 quadrants, absence of nausea/vomiting, good appetite, and adequate diet and food intake | Constipation, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, abdominal pain or distension, or excess flatulence |

| Genitourinary | Urine output greater than 30 mL/hr, clear urine, and urine specific gravity 1.000 to 1.030. In females, regular menstrual cycles | Decreased urine output less than 30 mL/hr or less than 0.5 mL/kg/hr, concentrated urine, or amenorrhea in females of child-bearing age |

| Weight | Normal BMI of 18.5-24.9, unintended weight loss less than 5% of weight over six months | BMI less than 18.5 or greater than 25, weight gain or weight loss of greater than 1 kg over 24 hrs, or unintended weight loss more than 10% of weight over six months |

Diagnosis (Analyze Cues)

After a comprehensive nutritional assessment is completed, relevant cues are recognized and analyzed, and nursing problems (diagnoses) are identified. See Table 3.5c for common nursing diagnoses related to nutrition.

Table 3.5c. NANDA Nursing Diagnoses Related to Nutrition[20]

| NANDA Nursing Diagnoses | Definition | Selected Defining Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Nutritional Intake | Insufficient nutrient consumption to meet metabolic needs |

|

| Risk for Inadequate Nutritional Intake | Susceptible to insufficient nutrient consumption to meet metabolic needs |

|

| Ineffective Overweight Self-Management | Unsatisfactory handling of treatment regimen, consequences, and lifestyle changes associated with accumulation of excess fat for age and gender |

|

| Ineffective Underweight Self-Management | Unsatisfactory handling of treatment regimen, consequences, and lifestyle changes associated with having a body weight less than standardized norms for age and gender |

|

| Readiness for Enhanced Nutritional Intake | Pattern of nutrient consumption to meet metabolic needs that can be strengthened |

|

Outcome Identification (Generate Solutions)

Goals for clients experiencing altered nutritional status depend on the selected nursing diagnosis and specific client situation. Typically, goals relate to resolution of the nutritional imbalance and are broad in nature, such as the client’s weight will be within normal range for their height and age. Outcome criteria are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time oriented. Sample SMART goals related to nutritional status are as follows[21]:

-

- The client will select three dietary modifications to meet their long-term nutritional goals using recommended guidelines by discharge.

- The client will achieve a BMI between 18.5 – 24.9 kg/m2 within six months.

Implementation (Take Action)

After SMART outcome criteria are customized to the client’s situation, nursing interventions are planned to help achieve identified outcomes. It is vital to consider the client’s cultural and religious beliefs and encourage clients to make healthy food selections based on their food preferences.

Nutrition Therapy

Interventions are specific to the alteration in nutritional status, current dietary guidelines, and history of existing chronic disease. The box below outlines selected interventions related to nutrition therapy.[22]

Nutrition Therapy[23]

- Monitor food/fluid ingested and calculate daily caloric intake, as appropriate

- Monitor appropriateness of diet orders to meet daily nutritional needs, as appropriate

- Determine in collaboration with the dietician, the number of calories and types of nutrients needed to meet nutritional requirements, as appropriate

- Determine food preferences with consideration of the client’s cultural and religious preferences

- Encourage nutritional supplements, as appropriate

- Provide clients with nutritional deficits high-protein, high-calorie, nutritious finger foods and drinks that can be readily consumed, as appropriate

- Determine need for enteral tube feedings in collaboration with a dietician

- Administer enteral feedings, as prescribed

- Administer parenteral nutrition, as prescribed

- Structure the environment to create a pleasant and relaxing meal atmosphere

- Present food in an attractive, pleasing manner, giving consideration to color, texture, and variety

- Provide oral care before meals

- Assist the client to a sitting position before eating or feeding

- Implement interventions to prevent aspiration in clients receiving enteral nutrition

- Monitor laboratory values, as appropriate

- Instruct the client and family about prescribed diets

- Refer for diet teaching and planning, as appropriate

- Give the client and family written examples of prescribed diet

Promoting Effective Weight Loss

Weight loss is a desired outcome for clients who are overweight or obese and have expressed readiness in doing so. Collaboration with a health care provider is important to ensure interventions are safe when developing a weight loss plan. Safe and effective weight-loss programs should focus on healthy lifestyle habits and not diet alone. Slow, steady weight loss, such as one to two pounds a week, is generally recommended.[24]

Many people are tempted by the marketing of fad diets, which promise quick, easy weight loss. Research shows fad diets do not work, or if people do lose weight, it is often temporary. If a fad diet eliminates entire food groups such as wheat or dairy, important nutrients are missed. Clients should be taught to avoid diets that contain the following[25]:

- A promise of quick, easy weight loss

- Something must be purchased

- Data that is vague or scientific sounding instead of research

- Endorsements from celebrities or influencers

Helping a Child Who is Overweight

Children who are overweight or obese are more likely to be obese as adults.[26] Encouraging healthy lifestyle habits, such as a healthy diet, daily physical activity, limited screen time, and adequate sleep can help overweight children achieve a healthy weight. The health care provider may refer children to a registered dietician to assist in developing a weight-loss plan that is safe for the child. Obese children between the ages of 6 and 11 are generally recommended to lose no more than one pound per month, while older children and adolescents should limit weight loss to two pounds a month. Parents can support their children’s weight loss by modeling healthy behaviors, such as regular exercise and healthy food choices. Healthy eating includes prioritizing fruits and vegetables over processed foods, limiting sweetened beverages, avoiding fast food, serving smaller portion sizes, and eating as a family.[27],[28]

Other Considerations at Mealtime to Promote Appetite

If a client has nutritional deficit, perform nursing interventions prior to mealtime to promote their appetite. For example, if the client has symptoms of pain or nausea, administer medications prior to mealtime to manage these symptoms. Do not perform procedures that may affect the client’s appetite, such as wound dressing changes, immediately prior to mealtime. Manage the environment prior to the food arriving and remove any unpleasant odors or sights. For example, empty the trash can of used dressings or incontinence products. If the client is out of the room when the meal tray arrives and the food becomes cold, reheat the food or order a new meal tray.[29]

When assisting clients to eat, help them to wash their hands and use the restroom if needed. Assist them to sit in a chair or sit in high Fowler’s position in bed. Set the meal tray on an overbed table and open containers as needed. Encourage the client to feed themselves as much as possible to promote independence. If a client has vision impairments, explain the location of the food using the clock method. For example, “Your vegetables are at 9 o’clock, your potatoes are at 12 o’clock, and your meat is at 3 o’clock.” When feeding a client, ask them what food they would like to eat first. Allow them to eat at their own pace with time between bites for thorough chewing and swallowing. If any signs of difficulty swallowing occur, such as coughing or gagging, stop the meal and notify the provider of suspected swallowing difficulties.[30]

Evaluation (Evaluate Outcomes)

Nurses evaluate the effectiveness of the nursing care plan to determine if the outcome criteria have been met, partially met, or not met. For example, sample criteria that may be used to evaluate a client diagnosed with Imbalanced Nutrition: Less than Body Requirements may include the following: stable or increasing weight; sufficient daily calories according to energy expenditure; well-balanced food intake; improved energy; and shiny hair, intact nails, and moist, intact skin.

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals 2E. WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals 2E. WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

- “2254477481” by Elaine Vigneault is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals 2E. WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals 2E. WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Assessing your weight. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/index.html ↵

- “Bmi-chart_colored.gif” by Cbizzy2313 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Assessing your weight. https://www.cdc.gov/healthyweight/assessing/index.html ↵

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine; Health and Medicine Division; Food and Nutrition Board; Roundtable on Obesity Solutions. (2023). Translating knowledge of foundational drivers of obesity into practice: Proceedings of a workshop series. National Academies Press, 10. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK594362/ ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals 2E. WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). Growth charts. https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/index.htm ↵

- This image is derived from “cj41c067.pdf” from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention National Center for Health Statistics and is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.cdc.gov/growthcharts/clinical_charts.htm#Set2 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Growth chart training. https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/index.htm ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Growth chart training. https://www.cdc.gov/nccdphp/dnpao/growthcharts/index.htm ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Why is it important to weigh and measure infants, children and adolescents accurately? https://depts.washington.edu/growth/module5/text/page1a.htm ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Why is it important to weigh and measure infants, children and adolescents accurately? https://depts.washington.edu/growth/module5/text/page1a.htm ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Why is it important to weigh and measure infants, children and adolescents accurately? https://depts.washington.edu/growth/module5/text/page1a.htm ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals 2E. WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals 2E. WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2024-2026 (13th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals 2E. WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals 2E. WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

- Butcher, H., Bulechek, G., Dochterman, J., & Wagner, C. (2018). Nursing interventions classification (NIC). Elsevier, p. 27. ↵

- National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2017). Choosing a safe & successful weight-loss program. National Institutes of Health. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/choosing-a-safe-successful-weight-loss-program ↵

- Williamson, L. (2022). Research says fad diets don’t work. So why are they so popular? American Heart Association. https://www.heart.org/en/news/2022/02/18/research-says-fad-diets-dont-work-so-why-are-they-so-popular ↵

- Drozdz, D., Alvarez-Pitti, J., Wójcik, M., et al. (2021). Obesity and cardiometabolic risk factors: From childhood to adulthood. Nutrients, 13(11), 1–20. https://doi.org/10.3390%2Fnu13114176 ↵

- National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. (2023). Helping your child who is overweight. National Institutes of Health. https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/weight-management/helping-your-child-who-is-overweight#reach ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022). Childhood obesity. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/childhood-obesity/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20354833 ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals 2E. WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing fundamentals 2E. WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/nursingfundamentals/ ↵

Aims to provide detailed information about food and beverages consumed by a client in the past 24 hours.

Also called a food diary, allows the client to record their intake in real-time over a specific period of time.

A nutritional assessment for clients over the age of 65.

The most commonly used assessment of a person’s weight.