3.3 Dietary Recommendations According to Age and Developmental Level

Dietary Guidelines

Nurses teach clients about healthy food choices based on current dietary guidelines. The Dietary Guidelines from the US Department of Agriculture provide four overarching guidelines that encourage healthy eating patterns at each stage of life, while also recognizing that most individuals will need to make shifts in their food and beverage choices to achieve a healthy pattern. The four guidelines include the following[1]:

- Follow a healthy dietary pattern at every life stage

- Customize and enjoy nutrient-dense food and beverage choices to reflect personal preferences, cultural beliefs, and budgetary considerations

- Focus on meeting food group needs with nutrient-dense foods and beverages, and stay within calorie limits

- Limit foods and beverages higher in added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium, and limit alcoholic beverages

An underlying premise of the 2020-2025 Dietary Guidelines is that nutritional needs should be met primarily from foods and beverages, specifically, nutrient-dense foods and beverages. Nutrient-dense foods provide vitamins, minerals, and other health-promoting components and have little or no added sugars, saturated fat, and sodium. A healthy dietary pattern consists of nutrient-dense forms of foods and beverages across all food groups, in recommended amounts, and within calorie limits.[2]

The core elements that make up a healthy diet include the following[3]:

- Vegetables of all types

- Fruits

- Grains, at least half of which are whole grain

- Dairy, including fat-free or low-fat milk, yogurt, cheese, and fortified soy beverages (Although soy beverages are not dairy products, they are nutritionally similar.)

- Proteins, including lean meats, poultry, eggs, seafood, beans, peas, lentils, nuts, seeds, and soy products

- Oils in food, such as in seafood and nuts

Foods high in added sugars, saturated fat, or sodium should be limited to the following amounts[4]:

- Added sugars: Less than 10 percent of calories per day starting at age two. For children younger than two, foods and beverages with added sugars should be avoided.

- Saturated fat: Less than 10 percent of calories per day starting at age two.

- Sodium: Less than 2,300 milligrams per day and even less for children younger than age 14.

- Alcoholic beverages: Those who drink alcohol should do so in moderation. Men should limit intake to two drinks or fewer per day, and women should limit intake to one drink or less per day. Some adults should not drink alcohol, such as women who are pregnant.

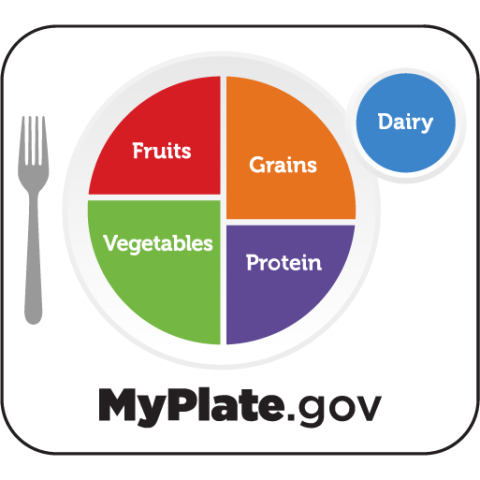

USDA MyPlate

USDA MyPlate is a tool to help people visualize how to achieve a healthy diet based on these dietary guidelines. When making food choices, clients should fill half of their plate with fruits and vegetables and the other half with grains and protein. Fruit and vegetable choices should be whole fruits and vegetables rather than juices. At least half of daily grain intake should be whole grain. Protein choices include lean meats, poultry, eggs, seafood, beans, peas, lentils, nuts, seeds, and soy products. Low-fat dairy beverages should be selected to supply calcium, vitamin B12, vitamin D, and other nutrients.[5] See Figure 3.4[6] for an illustration of the USDA MyPlate guidelines.

Read more about the USDA MyPlate guidelines.

The following subsections will further discuss dietary recommendations specific to various age groups and developmental levels.

Dietary Recommendations for Newborns and Infants

Teaching parents about good nutrition is critical because significant growth and development happens in the first year. Exclusive breastfeeding is recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics for the first six months of life and combined with food until one year of age.[7] While the frequency of feedings may vary, breastfeeding should occur on average every two to four hours or 8 to 12 times per day. See Figure 3.5[8] for an image of a mother breastfeeding her infant.

Human milk contains an array of bioactive compounds that keep newborns and young infants healthy. Bioactive compounds also help develop a healthy gut microbiome and immune system that can last a lifetime. There are three major groups of bioactive compounds in human milk called immunoglobulins, antimicrobials from protein, and oligosaccharides. Lipids deliver the antimicrobials to the newborn via human milk.[9] Research shows that breastfeeding is one of the best things a mother can do to protect her infant’s health. Human milk protects the infant against infection and inflammation, while providing optimal nutrition.[10]

Successful breastfeeding requires learning by the mother and the newborn. Nurses provide teaching to new mothers about breastfeeding, and certified lactation consultants provide specialized guidance.[11] A certified lactation consultant is a health professional who specializes in teaching about breastfeeding and offering human milk to infants. Clients can visit a lactation consultant while they are pregnant, right after giving birth, or several months into breastfeeding.[12]

Read more about lactation consultants on Cleveland Clinic’s website.[13]

Babies who are exclusively fed human milk or who receive both human milk and infant formula require vitamin D supplementation starting shortly after birth. Health care providers prescribe vitamin D drops, or the drops can also be purchased over the counter.[14]

If breastfeeding is not an option, expressed mother’s milk, pasteurized human milk from a donor, or infant formula may be used. The only infant formula approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) should be fed to infants up to 12 months of age. The FDA regulates commercial infant formulas to ensure they meet minimum nutritional and safety requirements. Iron-fortified infant formulas are recommended for most infants. Homemade, non-FDA approved formulas or toddler formulas should not be used. Most newborns will drink one to two ounces of infant formula about 8 to 12 times over 24 hours. The amount consumed and the amount of time between feedings increases as the baby grows, typically drinking 8 ounces every three to four hours by six months of age. After six months, the infant should be fed when showing signs of hunger, typically about five to six times over 24 hours. At 12 months of age, the infant can be transitioned to plain whole cow’s milk or fortified unsweetened soy beverage.[15]

Read more about breastfeeding in the “Applying the Nursing Process and Clinical Judgment Model to Newborn Care” section of the “Healthy Newborn” chapter.

The Dietary Guidelines for Americans and the American Academy of Pediatrics recommend children should be introduced to foods other than human milk or infant formula when they are about six months old and developmentally ready. Between age six and twelve months, infants should continue human milk or formula, along with solid foods, because human milk is still the most important source of nutrition.[16] The following criteria can be used to establish developmental readiness[17]:

- Sits up alone or with support

- Is able to control their head and neck

- Opens the mouth when food is offered

- Swallows food rather than pushes it back out onto the chin

- Brings objects to the mouth

- Tries to grasp small objects, such as toys or food

- Transfers food from the front to the back of the tongue to swallow

Foods should be introduced one type at a time, with three to five days between each new food, to monitor for food sensitivities. Potentially allergenic foods such as cow’s milk products, eggs, fish, shellfish, tree nuts, peanuts, wheat, soy, and sesame should be introduced as other foods are introduced.[18] Additionally, honey should not be given to infants less than one year of age due to the increased risk of botulism related to an immature gut.[19]

Initially, foods should be mashed, pureed, or strained and very smooth in texture. When initially eating their first foods, infants may cough, gag, or spit up, but as their oral skills develop, thicker and lumpier foods can be introduced.

Some foods are potential choking hazards, so it is important to feed infants foods that are the correct texture based on their development. To prevent choking, foods should be prepared that can be easily dissolved with saliva and do not require chewing. Small portions should be fed, and the infant should be encouraged to eat slowly. The child should always be supervised while eating in case choking occurs that requires rapid intervention.

Parents can modify foods for children under the age of four in the following ways to decrease the chance of choking while eating[20]:

- Cut round food, cheese, and hot dogs into pieces smaller than ½ inch

- Slice foods into small pieces or slices

- Remove seeds, pits, and tough skin

- Remove bones from meat or fish

- Grind tough meat or poultry

- Cook or steam hard foods such as vegetables until fork-tender

- Avoid sticky or hard food, including gum, candy, popcorn, ice cubes, and thick nut butter

Read more information on the CDC website about choking hazards for infants.

Dietary Recommendations for Children and Adolescents

Healthy dietary habits formed in childhood through adolescence help prevent obesity, cardiovascular disease, diabetes mellitus, and other chronic diseases later in life. Providing children with a variety of different foods prepared in different ways also increases their likelihood of accepting and growing accustomed to many foods. It is common for children to become picky in their food choices or decide to only eat one or a few different food items over a period of time. Allowing children to help select and prepare food can increase their acceptance of different food choices.[21] See Figure 3.6[22] for an image of a child with healthy food choices at a meal served at school.

See Table 3.3a for an overview of nutritional considerations for toddler, school-age, and adolescents.

Table 3.3a. Child and Adolescent Nutrition[23]

| Toddler/Preschool | School-Age/Pre-Pubescent | Adolescent | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Growth and Development Related to Nutrition |

|

|

|

| Teaching Topics for Parents |

|

|

|

| Selected Micronutrient Needs |

|

|

|

The role of a parent or a caregiver in feeding children and adolescents includes the following components[26]:

- Selecting and preparing food

- Providing regular meals and snacks

- Making mealtimes pleasant

- Teaching children about mealtime behavior

Childhood Obesity

Children need adequate intake of calories for growth, but regularly exceeding caloric requirements can lead to childhood obesity, which has become a major problem globally. Nearly one of three US children and adolescents is overweight or obese. Children with obesity are more likely to become overweight or obese adults. Obesity has a profound effect on self-esteem, energy, and activity level. Even more importantly, it is a major risk factor for a number of diseases later in life, including cardiovascular disease, type 2 diabetes, stroke, hypertension, and certain cancers.[27]

There are several factors underlying childhood obesity, including the following[28]:

- Larger portion sizes

- Limited access to nutrient-rich foods

- Increased access to fast foods and vending machines

- Lack of breastfeeding support

- Declining physical education programs in schools

- Insufficient physical activity

- Media messages encouraging the consumption of unhealthy foods

- Added sugars in foods

A major factor to childhood obesity is the consumption of added sugars. According to the National Center for Health Statistics, young children and adolescents consume an average of 322 calories per day from added sugars, or about 16 percent of daily calories. This does not include sugars that occur naturally in foods, such as the lactose in milk or the fructose in fruits. Added sugars refer to sugar added to food during a meal, as well as ingredients added to items such as bread, cookies, cakes, pies, jams, and soft drinks. Added sugar in store-bought items may be listed on the label as white sugar, brown sugar, high-fructose corn syrup, honey, malt syrup, maple syrup, molasses, anhydrous dextrose, crystal dextrose, and concentrated fruit juice. Sugars are also “hidden” in condiments and dressings, such as ketchup and salad dressing.[29]

Programs to address childhood obesity can include behavior modification, exercise counseling, psychological support or therapy, family counseling, and family meal-planning advice. For most children, the goal is not weight loss, but rather allowing height to catch up with weight as the child continues to grow. Rapid weight loss is not recommended for preteens or younger children due to the risk of deficiencies and stunted growth.[30]

To prevent or address childhood obesity, parents and caregivers can do the following[31]:

- Eat at the kitchen table as a family instead of in front of a television to monitor what and how much a child eats.

- Offer a child healthy portions. The size of a toddler’s fist is an appropriate serving size.

- Plan time for physical activity, about 60 minutes or more per day. Toddlers should have no more than 60 minutes of sedentary activity, such as watching television, per day.

- Avoid added sugars in food choices.

Dietary Recommendations for Adults

The adult life stage is from age 19 through 64. Poor nutritional habits early in life can contribute to unhealthy diet choices in adulthood. Unhealthy diet habits can be difficult to change due to food preferences and lack of knowledge about proper nutrition. Nurses provide teaching according to current dietary guidelines to help improve health and prevent chronic disease in adult clients.[32]

Dietary Recommendations During Pregnancy and Lactation

Good nutrition is vital during pregnancy and lactation, not only for the mother to remain healthy, but also for the health and development of the baby. During pregnancy, a woman’s needs increase for certain nutrients more than for others. If these nutritional needs are not met, infants could suffer from low birth weight (a birth weight less than 5.5 pounds or 2,500 grams) or other developmental problems. Therefore, it is crucial for pregnant women to make healthy dietary choices.[33]

During the first trimester, a pregnant woman has the same energy requirements and should consume the same number of calories as usual. However, as the pregnancy progresses, a woman must increase her caloric intake by an additional 340 kcal per day during the second trimester, and an additional 450 kcal per day during the third trimester. These increases are required for healthy fetal development, as well as increased metabolism during pregnancy. A woman can easily meet these increased needs by consuming more nutrient-dense foods.[34]

Extra protein is needed for the synthesis of new maternal and fetal tissues. Protein builds muscle and other tissues, enzymes, antibodies, and hormones in both the mother and the unborn baby. Additional protein also supports increased blood volume and the production of amniotic fluid. Protein should be derived from healthy sources, such as lean red meat, poultry, legumes, nuts, seeds, eggs, and fish. Low-fat milk and other dairy products also provide protein, along with calcium and other nutrients.[35]

The recommended amount of carbohydrates during pregnancy is about 175 to 265 grams per day to fuel fetal brain development, including an extra three mg/day of fiber. These foods also help to build the placenta and supply energy for the growth of the fetus.[36]

It is recommended to increase the amount of essential fatty acids (omega-3 and omega-6) because they are incorporated into the placenta and fetal tissues. Fats should make up 25-35% of daily kcal and should come from healthy sources, such as avocados, nuts and nut butters, and olives and olive oils. It is not recommended for pregnant women to be on a very low-fat diet because it would be difficult to meet the needs of essential fatty acids and fat-soluble vitamins. Fatty acids are important during pregnancy because they support the baby’s brain and eye development.[37]

Pregnant women should drink at least 2.3 liters (about ten cups) of liquids per day to provide enough fluid for blood production, with additional liquids during physical activity or when it is hot to replace fluids lost via perspiration. The combination of a high-fiber diet and lots of liquids also helps to eliminate waste.[38]

The daily requirements of vitamins and minerals for nonpregnant women change with the onset of a pregnancy. Taking a daily prenatal supplement or multivitamin helps to meet many nutritional needs. However, most of these requirements should be fulfilled with a healthy diet. Table 3.3b compares the nonpregnant levels of required vitamins and minerals to the levels needed during pregnancy. For pregnant women, the recommended daily allowance (RDA) of nearly all vitamins and minerals increases.[39]

Table 3.3b. Comparison of Recommended Vitamins and Minerals for Nonpregnant and Pregnant Women[40]

| Nutrient | Non-Pregnant Women | Pregnant Women |

|---|---|---|

| Vitamin A (mcg) | 700 | 770 |

| Thiamin (mg) | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| Riboflavin (mg) | 1.1 | 1.4 |

| Niacin (mg) | 14 | 18 |

| Vitamin B6 (mg) | 1.3 | 1.9 |

| Folate (mcg) | 400 | 600 |

| Vitamin B12 (mcg) |

2.4 | 2.6 |

| Vitamin C (mg) | 75 | 85 |

| Vitamin D (mcg) | 15 | 15 |

| Vitamin E (mg) | 15 | 15 |

| Calcium (mg) | 1,000 | 1,000 |

| Iron (mg) | 18 | 27 |

| Magnesium (mg) | 310 (age 19 – 30 years)

320 (age 31 – 50 years) |

350 (age 19 – 30 years)

360 (age 31-50 years) |

| Phosphorus (mg) | 700 | 700 |

| Zinc (mg) | 8 | 11 |

Folic acid is necessary during pregnancy to prevent neural tube defects such as spina bifida or brain abnormalities in the fetus during the first trimester of pregnancy. All women of childbearing age should take folic acid supplements of 400-800 mcg daily in case of unintended pregnancy due to the need for folate early in the pregnancy.[41] Increased iron is also needed during pregnancy to support fetal development and prevent maternal anemia.[42] Even if a woman consumes a healthy diet, an iron supplement is needed to meet the daily recommended amounts.[43]

The micronutrients involved with building bones (vitamin D and calcium) are crucial during pregnancy to support fetal bone development. Although the recommended levels are the same as those for nonpregnant women, many women do not typically consume adequate amounts and should make an extra effort to meet those needs. There is also an increased need for all B vitamins during pregnancy. Adequate vitamin B6 supports the metabolism of amino acids, while more vitamin B12 is needed for the synthesis of red blood cells and DNA. Additional zinc is crucial for cell development and protein synthesis.[44]

Foods to Avoid During Pregnancy

Many substances can harm a growing fetus and should be avoided during pregnancy. Some substances are so detrimental that a woman should avoid them if she suspects that she might be pregnant. For example, consumption of alcoholic beverages can cause a range of abnormalities that fall under the umbrella term of Fetal Alcohol Spectrum Disorders, including learning and attention deficits, heart defects, and abnormal facial features. Alcohol enters the unborn baby via the umbilical cord and can slow fetal growth, damage the brain, or even result in miscarriage. The effects of alcohol are most severe in the first trimester, when the organs are developing. As a result, there is no safe amount of alcohol that a pregnant woman can consume.[45]

Pregnant women should also limit caffeine intake, which is found not only in coffee, but also tea, colas, cocoa, chocolate, and some over-the-counter painkillers. Some studies suggest that very high amounts of caffeine have been linked to babies born with low birth weights. Most experts agree that small amounts of caffeine each day are safe, meaning approximately 200 mg/day (about 2 cups of coffee).[46]

Food-borne illness can cause major health problems in the mother and fetus. For example, the food-borne illness caused by the bacteria Listeria monocytogenes can cause spontaneous abortion or fetal or newborn meningitis. Pregnant women are ten times more likely to become infected with this disease than nonpregnant, healthy adults. Foods that may contain the bacteria and that should be avoided include unpasteurized dairy products, especially soft cheeses, smoked seafood, hot dogs, pâté, cold cuts, and uncooked meats.[47]

Pregnant women can eat fish, ideally 8 to 12 ounces of different types per week. Expectant mothers are able to eat cooked shellfish such as shrimp, farm-raised fish such as salmon, and a maximum of 6 ounces of albacore or white tuna. However, they should avoid fish with high methylmercury levels, such as shark, swordfish, and king mackerel. Pregnant women should also avoid consuming raw fish to avoid food-borne illness.[48]

Dietary Recommendations for Older Adults

Older adults aged 65 years and older have lower calorie needs than younger people, though they still require nutrient-dense foods. Caloric needs decrease due to decreased activity, decreased metabolic rates, and decreased muscle mass. Additionally, chronic disease and medications can cause decreased nutrient absorption. Protein is necessary to prevent loss of muscle mass, but protein is commonly underconsumed in older adults. Vitamin B12 deficiency is a common problem for older adults because absorption of vitamin B12 decreases with age and is also impacted with certain medications. Loneliness and poverty can also impact dietary intake in older adults.[49] The ability to chew and swallow food can also significantly impact an older adult’s ability to eat and enjoy food. Teaching about different textures of foods may help clients with these difficulties.[50]

Adequate hydration is also a concern for older adults because feelings of thirst decrease with age, leading to poor fluid intake. Older adults may also experience urinary incontinence, so they may consciously limit fluid intake to prevent incontinence.[51] They may also limit fluids in the evening to prevent frequent awakenings due to the need to urinate at night.

Nurses can support older adults in improving their food intake in several ways. First, the client’s food preferences and cultural/religious beliefs must be considered. Clients are more likely to eat foods they enjoy. The environment should also be considered. Eating is commonly a social activity, so opportunities to share mealtimes with others should be encouraged. Meals on Wheels, local senior centers, and other community programs can provide socialization and well-balanced meals to older adults.[52] See Figure 3.7[53] for an image of older adults socializing at mealtime during a community food pantry.

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/ ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/ ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/ ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/ ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/ ↵

- “MyPlate” by U.S. Department of Agriculture is in the Public Domain. ↵

- American Academy of Pediatrics. (n.d.). Breastfeeding. https://www.healthychildren.org/English/ages-stages/baby/breastfeeding/Pages/default.aspx ↵

- “Breastfeeding a Newborn Child” by Vyacheslav Argenberg is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Zempleni, S. (2020). Nutrition through the life cycle. https://pressbooks.nebraska.edu/nutr251/ ↵

- Camacho-Morales, A., Caba, M., García-Juárez, M., Caba-Flores, M. D., Viveros-Contreras, R., & Martínez-Valenzuela, C. (2021). Breastfeeding contributes to physiological immune programming in the newborn. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 9(744104). https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2021.744104 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Nutrition. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/ ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2024). Lactation consultant. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/22106-lactation-consultant ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2024). Lactation consultant. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/22106-lactation-consultant ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Nutrition. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Nutrition. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022). How much and how often to breastfeed. https://www.cdc.gov/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Nutrition. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Nutrition. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Foods and drinks to avoid or limit. https://www.cdc.gov/ ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture. (2020). Reducing the risk of choking in young children at mealtimes. [PDF]. https://wicworks.fns.usda.gov/sites/default/files/media/document/English_ReducingRiskofChokinginYoungChildren.pdf ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/ ↵

- “7042900703_67a6561b04_4k” by unknown author at the U.S. Department of Agriculture is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Titchenal, A., Hara, S., Caacbay, N. A., Yang, Y.-Y., Revilla, M. K. F., Draper, J., Langfelder, G., Gibby, C., Chun, C. N., Calabrese, A., & Young, C. G. L. (2020). Toddler Years. In: Human Nutrition 2020 Edition. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program and Human Nutrition Program. https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition2/chapter/13-toddler-years/ ↵

- Office of Dietary Supplements. (2024). Vitamin B12. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminB12-HealthProfessional/ ↵

- Office of Dietary Supplements. (2021). Vitamin K. https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminK-HealthProfessional/ ↵

- Titchenal, A., Hara, S., Caacbay, N. A., Yang, Y.-Y., Revilla, M. K. F., Draper, J., Langfelder, G., Gibby, C., Chun, C. N., Calabrese, A., & Young, C. G. L. (2020). Toddler Years. In: Human Nutrition 2020 Edition. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program and Human Nutrition Program. https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition2/chapter/13-toddler-years/ ↵

- Titchenal, A., Hara, S., Caacbay, N. A., Yang, Y.-Y., Revilla, M. K. F., Draper, J., Langfelder, G., Gibby, C., Chun, C. N., Calabrese, A., & Young, C. G. L. (2020). Toddler Years. In: Human Nutrition 2020 Edition. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program and Human Nutrition Program. https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition2/chapter/13-toddler-years/ ↵

- Titchenal, A., Hara, S., Caacbay, N. A., Yang, Y.-Y., Revilla, M. K. F., Draper, J., Langfelder, G., Gibby, C., Chun, C. N., Calabrese, A., & Young, C. G. L. (2020). Toddler Years. In: Human Nutrition 2020 Edition. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program and Human Nutrition Program. https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition2/chapter/13-toddler-years/ ↵

- Titchenal, A., Hara, S., Caacbay, N. A., Yang, Y.-Y., Revilla, M. K. F., Draper, J., Langfelder, G., Gibby, C., Chun, C. N., Calabrese, A., & Young, C. G. L. (2020). Toddler Years. In: Human Nutrition 2020 Edition. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program and Human Nutrition Program. https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition2/chapter/13-toddler-years/ ↵

- Titchenal, A., Hara, S., Caacbay, N. A., Yang, Y.-Y., Revilla, M. K. F., Draper, J., Langfelder, G., Gibby, C., Chun, C. N., Calabrese, A., & Young, C. G. L. (2020). Toddler Years. In: Human Nutrition 2020 Edition. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program and Human Nutrition Program. https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition2/chapter/13-toddler-years/ ↵

- Titchenal, A., Hara, S., Caacbay, N. A., Yang, Y.-Y., Revilla, M. K. F., Draper, J., Langfelder, G., Gibby, C., Chun, C. N., Calabrese, A., & Young, C. G. L. (2020). Toddler Years. In: Human Nutrition 2020 Edition. University of Hawai‘i at Mānoa Food Science and Human Nutrition Program and Human Nutrition Program. https://pressbooks.oer.hawaii.edu/humannutrition2/chapter/13-toddler-years/ ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/ ↵

- Riggs, K. (2024). Clinical nutrition. Nova Scotia Community College. https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/clinicalnutrition/ ↵

- Riggs, K. (2024). Clinical nutrition. Nova Scotia Community College. https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/clinicalnutrition/ ↵

- Riggs, K. (2024). Clinical nutrition. Nova Scotia Community College. https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/clinicalnutrition/ ↵

- Riggs, K. (2024). Clinical nutrition. Nova Scotia Community College. https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/clinicalnutrition/ ↵

- Riggs, K. (2024). Clinical nutrition. Nova Scotia Community College. https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/clinicalnutrition/ ↵

- Riggs, K. (2024). Clinical nutrition. Nova Scotia Community College. https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/clinicalnutrition/ ↵

- Riggs, K. (2024). Clinical nutrition. Nova Scotia Community College. https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/clinicalnutrition/ ↵

- Riggs, K. (2024). Clinical nutrition. Nova Scotia Community College. https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/clinicalnutrition/ ↵

- Anderson-Villaluz, D., & Quam, J. (2022). Nutrition during pregnancy to support a healthy mom and baby. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. https://health.gov/news/202202/nutrition-during-pregnancy-support-healthy-mom-and-baby ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/ ↵

- Riggs, K. (2024). Clinical nutrition. Nova Scotia Community College. https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/clinicalnutrition/ ↵

- Riggs, K. (2024). Clinical nutrition. Nova Scotia Community College. https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/clinicalnutrition/ ↵

- Riggs, K. (2024). Clinical nutrition. Nova Scotia Community College. https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/clinicalnutrition/ ↵

- Riggs, K. (2024). Clinical nutrition. Nova Scotia Community College. https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/clinicalnutrition/. ↵

- Riggs, K. (2024). Clinical nutrition. Nova Scotia Community College. https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/clinicalnutrition/ ↵

- Riggs, K. (2024). Clinical nutrition. Nova Scotia Community College. https://pressbooks.nscc.ca/clinicalnutrition/ ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/ ↵

- DeSilva, D., & Anderson-Villaluz, D. (2021). Nutrition as we age: Healthy eating with the dietary guidelines. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. https://health.gov/news/202107/nutrition-we-age-healthy-eating-dietary-guidelines#:~:text=Eating%20more%20fruits%2C%20vegetables%2C%20whole,%2C%20saturated%20fat%2C%20and%20sodium ↵

- U.S. Department of Agriculture and U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (2020). Dietary guidelines for Americans, 2020-2025 (9th ed.). https://www.dietaryguidelines.gov/ ↵

- DeSilva, D., & Anderson-Villaluz, D. (2021). Nutrition as we age: Healthy eating with the dietary guidelines. Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotion. https://health.gov/news/202107/nutrition-we-age-healthy-eating-dietary-guidelines#:~:text=Eating%20more%20fruits%2C%20vegetables%2C%20whole,%2C%20saturated%20fat%2C%20and%20sodium ↵

- “42830964240_144653038a_o” by unknown author at the U.S. Department of Agriculture is in the Public Domain. ↵

A health professional who specializes in breastfeeding and in offering human milk to infants.

Severe birth defects of the brain and spine that occur when the neural tube, an embryonic structure that develops into the spinal cord and brain, doesn't close completely during pregnancy.