20.6 Congenital and Genetic Disorders

Congenital disorders, commonly known as birth defects, are structural or functional abnormalities that exist before birth, whereas a genetic disorder is caused by an chromosomal abnormality. Common, severe congenital disorders are heart defects, gastrointestinal defects, or neural tube defects. Examples of genetic disorders covered in this chapter are Trisomy 21 and Trisomy 18. These disorders may be known or unknown at the time of birth. Congenital and genetic disorders may cause long-term disabilities that significantly impact children and their families.[1],[2]

Congenital Heart Defects

Congenital cardiac defects can be divided into cyanotic defects that shunt blood from the right side of the heart to the left (resulting in oxygen saturations of less than 90 percent) and acyanotic defects that shunt blood from left side of the heart to right (resulting in oxygen saturations of 90 percent and above). Congenital heart disease is one of the most common birth anomalies affecting neonates and one of the most survivable because of surgical and medical management.

Read more details about congenital heart defects in the “Congenital Heart Defects” chapter.

Congenital Defects of the Gastrointestinal System

Common congenital defects of the gastrointestinal system are esophageal atresia, transesophageal fistula, gastroschisis, and omphalocele.

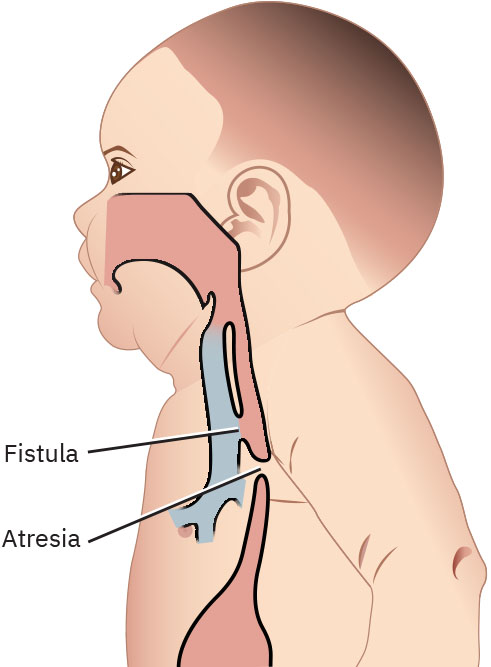

Esophageal Atresia and Tracheoesophageal Fistula

Esophageal atresia (EA) occurs when the fetal esophagus does not develop properly and the esophagus has two separate sections, an upper and lower, that do not connect. An infant with this condition is unable to pass food from the mouth to the stomach. Esophageal atresia often occurs with a tracheoesophageal fistula, where part of the esophagus connects to the trachea. The connection between the trachea and esophagus causes the infant to aspirate oral liquids that cross from the esophagus into the trachea and subsequently into the lungs. See Figure 20.6[3] for an illustration of an esophageal atresia and tracheoesophageal fistula. Nearly half of all babies born with esophageal atresia have one or more additional birth defects. For example, VACTERL syndrome is an acronym that stands for Vertebral defects, Anal atresia, Cardiac defects, TracheoEsophageal fistula, Renal anomalies, and Limb abnormalities.[4],[5]

The most common signs of EA are the “Three Cs” that occur during feeding: Coughing, Choking, and Cyanosis. EA can be diagnosed by attempting to pass an oral or nasal catheter into the infant’s stomach and not being able to reach it. With the catheter in place, chest and abdominal X-rays are performed to confirm the abnormal esophagus.[6]

Treatment includes surgery to connect the esophagus to the stomach and to disconnect the trachea and esophagus if a fistula is present. The neonate is NPO with no oral or gastric feedings or medications, with nutrition provided by parenteral nutrition. Postoperatively, an esophagram is obtained on approximately postoperative Day 5 to evaluate for a leak. If there is no leak after surgical intervention, feedings can be started. Anti-reflux medication is also typically prescribed postoperatively.[7]

Gastroschisis and Omphalocele

Gastroschisis and omphalocele are two types of congenital abdominal wall defects. Gastroschisis is a hole in the abdominal wall beside the umbilicus, often on the right side, resulting in the infant’s intestines extending outside of their body. Sometimes other organs, such as the stomach and liver, can be found outside of the baby’s body. Gastroschisis occurs early during pregnancy, and because the intestines are exposed to the amniotic fluid because they are not covered in a protective sac, they can become irritated and shorten, twist, or swell in utero.[8],[9]

Another type of abdominal wall defect is omphalocele, where the fetal intestines, liver, or other organs stick outside of the abdomen through the umbilicus, and the organs are covered in a thin, nearly transparent sac that usually is intact at birth. During normal fetal development, the fetal intestines normally get longer and push out into the umbilical cord during early pregnancy, but by the eleventh week, the intestines normally recede back into the abdomen. However, if this development does not happen, an omphalocele occurs.[10] The omphalocele can be small, with only some of the intestines outside of the abdomen, or it can be large, with many organs outside of the abdomen. Infants born with an omphalocele may have additional complications. Their abdominal cavity might not grow to its normal size, or an organ might become compressed or twisted, resulting in organ damage from loss of blood flow. Babies born with an omphalocele often have other birth defects, such as heart defects, neural tube defects, and chromosomal abnormalities.[11] See Figure 20.7[12] for an illustration comparing gastroschisis and omphalocele.

Most cases of gastroschisis and omphalocele are diagnosed during pregnancy on routine prenatal ultrasounds. Gastroschisis may be treated prenatally with amnioexchange, where the amniotic fluid is removed and replaced with normal saline because amniotic fluid is inflammatory to the exposed bowels. Another potential treatment is fetoscopic intervention, where the intestines are placed into the abdominal space, and the defect is surgically closed while the fetus is still in utero. A fetus with omphalocele is typically delivered by cesarean section due to risk for sac rupture.[13]

Corrective surgery, if not performed in utero, is performed soon after birth. The neonate with gastroschisis or omphalocele is cared for in a NICU both before and after surgery. After the repair, infants may have problems with digesting food and absorbing nutrients and may require parenteral nutrition.[14]

Neural Tube Defects

Neural tube defects (NTDs) are the most common types of birth defects in the United States, affecting about 1 in 1,000 births.[15] The neural tube is a narrow channel that folds and closes during the third and fourth weeks of pregnancy. As the neural tube forms and closes, the upper part helps form the fetal brain and skull. The lower part of the neural tube helps form the spinal cord and back bones. Neural tube defects refer to problems that occur when the neural tube does not close properly. Risk factors for NTDs include the following[16]:

- Genetic factors

- Low folate (vitamin B9) levels during early pregnancy

- Preexisting health conditions, such as diabetes, that are not well-controlled

- Certain medications, such as antiseizure medications

- Overheating (like getting in a hot tub) or fever

NTDs are typically diagnosed during pregnancy based on serum alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) screening and follow-up testing.

Review information about alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) tests in the “Second Trimester Prenatal Care” section of the “Antepartum Care” chapter.

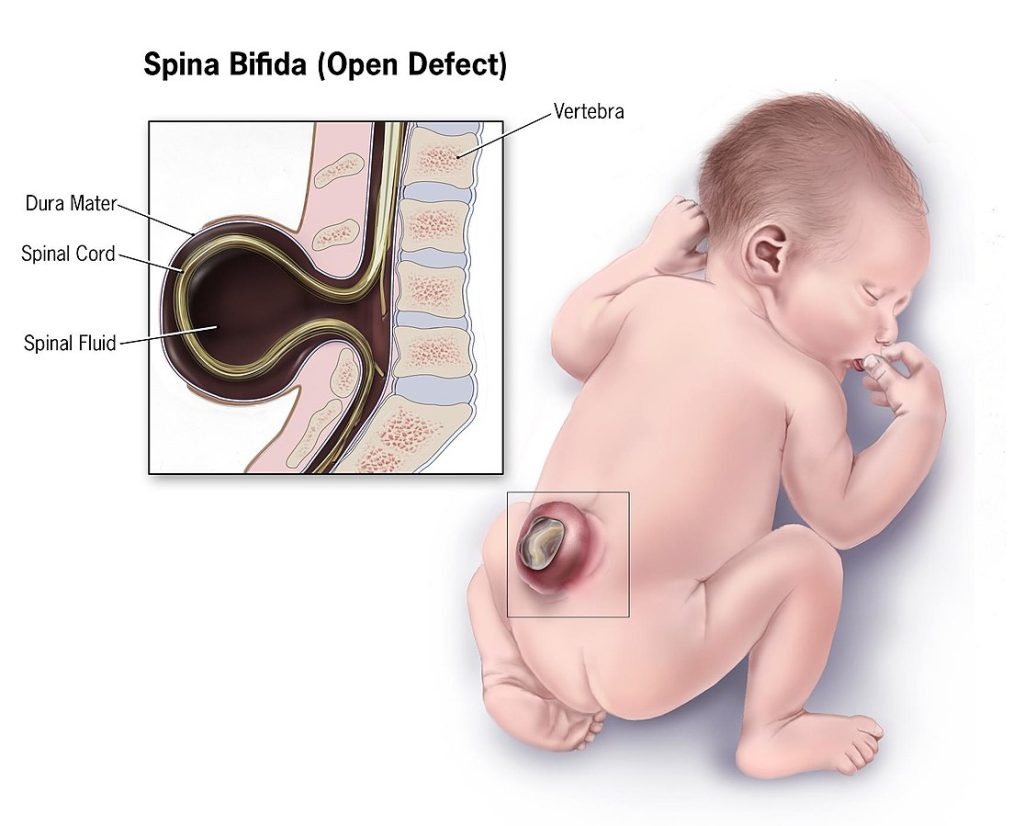

There are three major types of NTDs, including spina bifida, encephalocele, and anencephaly. Spina bifida affects about 1,300 babies a year in the United States.[17] Spina bifida can happen anywhere along the spine when the neural tube does not close all the way. See Figure 20.8[18] for an illustration of spina bifida.

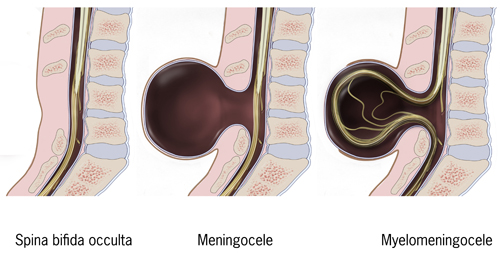

The symptoms of spina bifida are different from person to person, depending on the type and severity of the problems in brain and spinal cord development. There are four types of spina bifida called occulta, closed neural tube defects, meningocele, and myelomeningocele[19]:

- Occulta: Occulta is the mildest and most common type of spina bifida. It happens when one or more vertebrae do not form correctly. Occulta means “hidden” because a layer of skin covers and hides the opening in the spine. Typically, there are no symptoms with occulta, and it is found incidentally on an X-ray performed for another reason.

- Closed neural tube deficit: Closed neural tube defects are a diverse group of disorders that occur when the spine has abnormal forms of fat, bone, or protective layers (called meninges) that cover the spinal cord. Many of these neural tube defects require surgery in childhood. Children with this type of spina bifida may have leg weakness and trouble controlling their bowels and bladder that can worsen as they grow.

- Meningocele: Meningocele happens when the meninges stick out through the spine and expose a sac of spinal fluid on the back. This sac contains no nerves and may or may not be covered by a layer of skin. People with meningocele may have minor symptoms.

- Myelomeningocele: Myelomeningocele is the most severe form of spina bifida that occurs when an opening in the spine exposes part of the spinal cord or nerves through a sac that sticks out from the spinal cord. The meninges may or may not cover the sac. The opening can be closed during surgery performed on the fetus in utero or shortly after the baby is born. Most people born with myelomeningocele experience changes in brain structure, leg weakness, and problems with their bladder and bowels.

See Figure 20.9[20] for an illustration comparing spina bifida occulta, meningocele, and myelomeningocele.

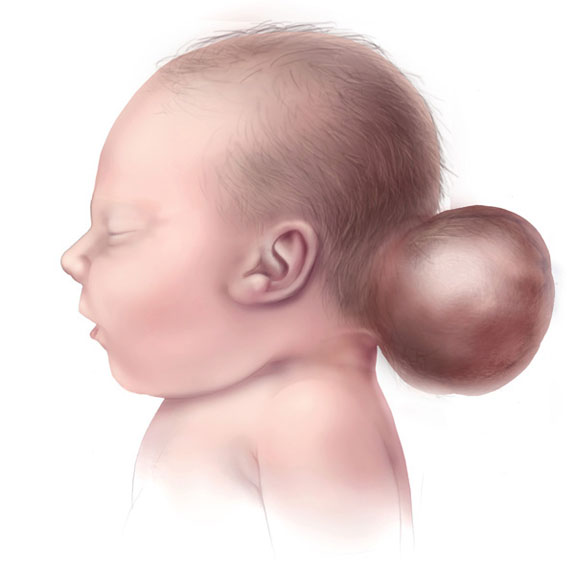

Encephalocele is a rare type of NTD where a sac-like protrusion of brain tissue comes out of an opening in the skull, commonly at the back of the head, the top of the head, or between the forehead and the nose. An encephalocele at the back of the skull is more likely to cause nervous system problems. Multiple surgeries may be required to treat encephalocele and place the protruding part of the brain back into the skull.[21] See Figure 20.10[22] for an illustration of encephalocele.

Anencephaly is a severe, fatal NTD that occurs when the forebrain (front part of the brain) and the cerebrum (thinking and coordinating part of the brain) do not develop during the embryonic period and are missing at birth. Bone or skin does not cover the remaining parts of the brain. There is no treatment for anencephaly and the newborn typically dies shortly after birth.[23] See Figure 20.11[24] for an illustration of anencephaly.

Genetic Disorders

Genetic disorders are an inherited medical condition caused by a DNA abnormality in a chromosome or gene. Examples of genetic disorders are Trisomy 21, Trisomy 18, and Trisomy 13.[25]

Trisomy 21

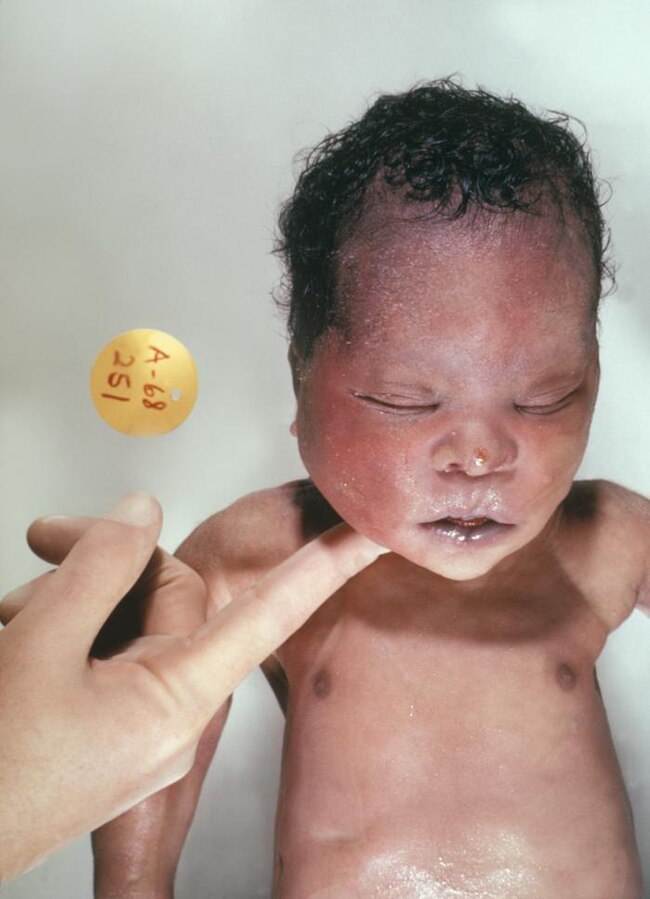

Trisomy 21, often called Down syndrome, is the most commonly occurring chromosomal anomaly, occurring in about 5,700 infants born every year in the United States. It is caused by an error during cell division in the egg or sperm, resulting in an extra chromosome 21 contained in every cell of the individual’s body. Distinct signs of Down syndrome are usually present at birth and become more apparent as the baby grows. See Figure 20.12[26] for an image of a newborn with Down syndrome. Signs of Down syndrome include the following[27]:

- A flattened face, especially the bridge of the nose

- Almond-shaped eyes that slant up

- A tongue that tends to stick out of the mouth

- A short neck

- Small ears, hands, and feet

- A single line across the palm of the hand (palmar crease)

- Small pinky fingers

- Poor muscle tone or loose joints

- Shorter-than-average height

- Developmental delays and cognitive disabilities

Common health problems associated with Down syndrome include congenital heart defects, hearing loss, and obstructive sleep apnea. Signs of Down syndrome are typically discovered on routine prenatal screening tests, such as ultrasound measurements of fetal nuchal translucency. Follow-up diagnostic tests include amniocentesis or chorionic villus sampling with genetic analysis.[28]

Infants born with Trisomy 21 may require multiple levels of care depending upon the disorders that are present. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends an evaluation by a cardiologist early in the infant period.[29]

Trisomy 18 and Trisomy 13 Syndromes

Trisomy 18 and Trisomy 13 are genetically distinct diseases but have similar characteristics with poor survival rates. Pregnancies with these syndromes often end in spontaneous abortion (i.e., miscarriage). Most infants with Trisomy 18 have three copies of Chromosome 18 in all their cells, and infants with Trisomy 13 have three copies of Chromosome 13 in all their cells. If they survive to childbirth, many have severe anomalies that cause death in the first months of life. Children who do survive past infancy often have significant developmental and motor disabilities. Pregnancies with suspected genetic disorders benefit from early diagnosis and multidisciplinary care from geneticists, neonatologists, social workers, and developmental specialists.[30]

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/maternal-newborn-nursing ↵

- World Health Organization. (2023). Congenital disorders. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/birth-defects ↵

- “72fbd758358371e8d9004b201aa5fb4da7c8a4d9” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/maternal-newborn-nursing ↵

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Esophageal atresia. https://www.cdc.gov/birth-defects/about/esophageal-atresia.html#:~:text=What%20it%20is,to%20the%20trachea%2C%20or%20windpipe ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/maternal-newborn-nursing ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/maternal-newborn-nursing ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/maternal-newborn-nursing ↵

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Gastroschisis. https://www.cdc.gov/birth-defects/about/gastroschisis.html#:~:text=What%20it%20is,shorten%2C%20twist%2C%20or%20swell.&text=Gastroschisis%20can%20be%20diagnosed%20prenatally ↵

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Omphalocele. https://www.cdc.gov/birth-defects/about/omphalocele.html#:~:text=Risk%20factors,Pre%2Dpregnancy%20obesity4 ↵

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Omphalocele. https://www.cdc.gov/birth-defects/about/omphalocele.html#:~:text=Risk%20factors,Pre%2Dpregnancy%20obesity4 ↵

- “Gastroschisis and Omphalocele” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/maternal-newborn-nursing ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/maternal-newborn-nursing ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/maternal-newborn-nursing ↵

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Neural tube defects. https://www.cdc.gov/birth-defects/about/neural-tube-defects.html ↵

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Neural tube defects. https://www.cdc.gov/birth-defects/about/neural-tube-defects.html ↵

- “Spina-bifida” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. ↵

- National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke. (2025). Spinal bifida. https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/spina-bifida ↵

- "Typesofspinabifida" by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. ↵

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Neural tube defects. https://www.cdc.gov/birth-defects/about/neural-tube-defects.html ↵

- “Encephalocele-web” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. ↵

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Neural tube defects. https://www.cdc.gov/birth-defects/about/neural-tube-defects.html ↵

- “Anencephaly-web” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Center on Birth Defects and Developmental Disabilities is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/maternal-newborn-nursing ↵

- “Newborn_with_Down_Syndrome” by Dr. Godfrey P. Oakley is in the Public Domain. ↵

- U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Down syndrome. https://www.cdc.gov/birth-defects/about/down-syndrome.html#:~:text=Trisomy%2021,of%20people%20with%20Down%20syndrome ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/maternal-newborn-nursing ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/maternal-newborn-nursing ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/details/books/maternal-newborn-nursing ↵

Conditions present at birth, often due to genetic or environmental factors, affecting the structure or function of organs.

A disorder caused by abnormalities in the DNA, either inherited or occurring spontaneously.

Congenital heart defects that result in reduced oxygenation of blood, causing a bluish tint to the skin (cyanosis).

Congenital heart defects that do not significantly affect oxygenation but may lead to other circulatory problems.

A congenital condition where the esophagus is malformed, often leading to feeding and swallowing difficulties.

A congenital defect where an abnormal connection forms between the trachea and esophagus, often associated with esophageal atresia.

A group of congenital abnormalities, including Vertebral defects, Anal atresia, Cardiac defects, Tracheoesophageal fistula, Esophageal atresia, Renal abnormalities, and Limb defects.

Coughing, Choking, and Cyanosis.

A birth defect where the intestines protrude outside the body through an opening in the abdominal wall.

A congenital defect where the abdominal organs protrude into the umbilical cord, covered by a membrane

A procedure in which amniotic fluid is replaced to treat fetal conditions like polyhydramnios or meconium aspiration.

Severe birth defects of the brain and spine that occur when the neural tube, an embryonic structure that develops into the spinal cord and brain, doesn't close completely during pregnancy.

A narrow channel that folds and closes during the third and fourth weeks of pregnancy.

A neural tube defect where the spinal cord and vertebrae do not fully form, leading to potential paralysis or other neurological impairments.

A less severe form of spina bifida, where the spinal cord is malformed but the neural tube remains intact.

A type of spina bifida where the meninges (protective covering of the brain and spinal cord) protrude through an opening in the vertebrae, without the spinal cord.

A more severe form of spina bifida, where both the meninges and spinal cord protrude through an opening in the spine, causing nerve damage and potential paralysis.

A neural tube defect where brain tissue protrudes through an opening in the skull.

A lethal condition where the fetal brain and skull do not form properly.

A genetic condition where an individual has three copies of chromosome 21, leading to intellectual and developmental delays, and characteristic physical features.

A genetic condition that affects brain and body development due to an extra chromosome number 21.