12.5 Applying the Nursing Process and Clinical Judgment Model to Newborn Care

This section will apply the nursing process and NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model to providing normal newborn care. The steps of the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model are included in parentheses after the steps of the nursing process.

Assessment (Recognize Cues)

Physical assessment of the newborn begins at the time of birth to evaluate their transition from the intrauterine environment to the extrauterine environment.

Apgar Scores

A quick assessment is performed at one and five minutes of life to provide an Apgar score. The Apgar score is a tool used to evaluate how well the newborn is tolerating the transition from fetal to neonatal circulation. The test is usually performed by the nurse or health care provider who is responsible for examining the newborn immediately after delivery. The assessment focuses on five areas, including heart rate, breathing effort, muscle tone, reflexes, and skin color. Each of the five areas is assigned a score from 0 to 2, depending on the assessment. The pulse is the most important indicator and is assessed using a stethoscope.[1] See a summary of Apgar scoring in Table 12.5a.

Table 12.5a. Apgar Scoring

| Indicator | 0 Points | 1 Point | 2 Points | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Activity (muscle tone) | Absent, loose, flaccid without activity; flappy tone | Arms and legs flexed with little movement | Spontaneous, active motion with flexed muscle tone resisting extension |

| P | Pulse | Absent | Less than 100 beats per minute | Greater than 100 beats per minute |

| G | Grimace (reflex or irritability in response to stimulation) | Zero response to stimulation | Limited response to stimulation | Crying, movement, pulling away upon stimulation |

| A | Appearance (skin color) | Pale or blue | Pink, but extremities are blue | Entirely pink |

| R | Respirations | Not breathing | Slow and irregular, weak or gasping | Crying vigorously |

The scores are added to give a total score out of a possible 10 points. A score of 7-10 is normal and a sign that the newborn is in good health. However, a score of ten is very unusual because almost all newborns lose one point for blue hands and feet (i.e., acrocyanosis), which is normal after birth. Any score lower than seven is a sign that the infant needs medical attention. The lower the score, the more medical assistance the infant requires to adjust to life outside the mother’s womb. A low Apgar score is often caused by a difficult birth, C-section, or fluid in the baby’s airway. An infant with a low Apgar score may require oxygen and clearing out the airway to help with breathing, physical stimulation to stimulate the heart beating at a healthy rate, or more extensive resuscitation efforts.[2] Medical interventions based on Apgar score are described in Table 12.5b.

Table 12.5b. Newborn Resuscitation Efforts Based on Apgar Score

| APGAR Score | Resuscitation Efforts |

|---|---|

| 7-10 | Routine post-delivery care |

| 4-6 | Some resuscitation (oxygen, suction, stimulate baby, rub back) |

| 0-3 | Full resuscitation |

View a supplementary YouTube video[3] from RegisteredNurseRN on performing an Apgar score: APGAR Newborn Assessment Score Scale Test Made Easy w/ NCLEX Practice Questions.

Ballard Score

The Ballard Score, also known as the Ballard Maturational Assessment, is a tool used to determine a newborn’s gestational age. The score is calculated by adding together scores from six physical signs and six neuromuscular signs of maturity, with each sign scoring between -1 and 5. The total score ranges from -10 to 50, with higher scores indicating a more mature gestational age and lower scores indicating a less mature gestational age.[4]

Visit perinatology.com’s web page to view the Ballard Score calculator.

Routine Newborn Assessment

After it is determined the newborn is transitioning well using Apgar scoring, a thorough head-to-toe assessment is performed by the nurse after the mother and newborn have had the opportunity to bond because skin-to-skin contact is recommended during the first hours of life. Ongoing assessments are routinely performed by the nurse according to facility policy. Most of the physical assessment can be obtained while the newborn remains with the mother.

Normal assessment findings for a healthy newborn differ from those of the adult. Nurses must be familiar with normal findings and promptly report abnormal findings to the health care provider that warrant action. Normal assessment findings for a healthy, term newborn are described by body system in the following subsections.

Vital Signs, Weight, Length, and Head Circumference

Normal ranges for newborn vital signs, weight, length, and head circumference at 40 weeks’ gestation are summarized in Table 12.5c.[5]

Table 12.5c. Normal Newborn Vital Signs[6]

| Vital Sign | Normal Range |

|---|---|

| Heart rate | 120-160 beats per minute |

| Respiratory rate | 40-60 breaths per minute |

| Systolic blood pressure | 60 to 90 mmHg |

| Temperature | 99.7-99.5 F (35.6 – 37.5 C) |

| Weight | Females 3.5 kg (7 lb 12 oz) Range 2.8 to 4.8 kg (6 lb 3 oz to 8 lb 14 oz)

Males 3.6 kg (8 lb) Range 2.9 to 4.2 kg (6 lb 7 oz to 9 lb 5 oz) |

| Length | 20 in (51 cm) Range 19 -21 in (48 to 53 cm) |

| Head circumference | 14 in (35 cm) Range 13-15 in (33 to 37cm) |

Head

Assessment of the newborn’s head includes assessing its size, shape, and symmetry. Nurses measure and document the circumference of the newborn’s head above the eyebrows and ears, which should range from 13 to 15 inches (33-37 cm).[7]

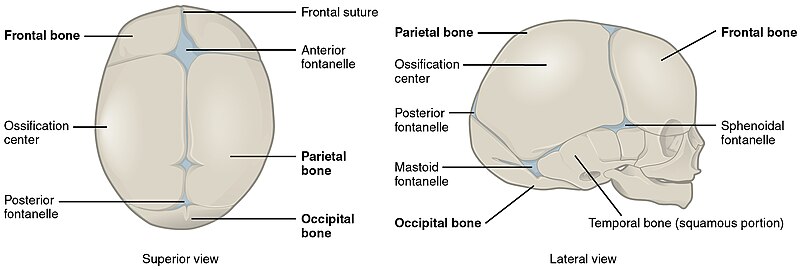

With the newborn in an upright position, the fontanelles should be palpated gently to assess for bulging or depression. Normally, the fontanelles are soft and flat. Bulging fontanelles may indicate increased intracranial pressure, and depression of the fontanelle may indicate dehydration. The anterior fontanelle is diamond-shaped, approximately 3 to 6 cm in diameter, while the posterior fontanelle is much smaller and only about 1 to 1.5 cm in diameter.[8] The anterior fontanelle closes between 13 and 24 months, while the posterior fontanelle closes six to eight weeks after birth.[9]

While palpating the fontanelles, the sutures can also be assessed. Sutures or suture lines are the borders where the bony plates of the skull intersect. The plates allow for the movement of the skull as the newborn goes through the birth canal. It is not unusual to see overlap of the bony plates in the immediate newborn period, as pressure from birth compresses the head. Following delivery, the head is relieved of pressure, and over the next few days, the head expands, allowing the plates to meet edge-to-edge.[10]

See Figure 12.9[11] for an illustration of a newborn skull.

Assessment of the head may reveal the newborn has caput succedaneum, a cephalohematoma, or other lesions. Caput succedaneum is edema of the scalp that occurs due to pressure exerted on the head during delivery. This swelling may cross the suture lines and is often noted shortly after birth, particularly in vacuum or forceps-assisted deliveries and in newborns born to first-time mothers. Parents may express concern about the “cone” shape of the newborn’s head due to the swelling but should be reassured that the edema usually resolves within 48 hours.[12]

Cephalohematoma differs from caput succedaneum in that it is limited by the suture lines and may worsen rather than improve in the first 48 hours of life. A cephalohematoma is swelling caused by an accumulation of blood under the scalp due to rupture of blood vessels during a prolonged, difficult, or assisted birth. Bruising may be noted in the area of swelling, which will usually increase in size in the days following delivery and then take several weeks to months to fully resolve. Newborns with a large cephalohematoma should be observed for infection, jaundice, and anemia, as blood is taken from the circulatory system. Newborns who develop a cephalohematoma are at increased risk for jaundice as there is an increase in the breakdown of red blood cells in the area.[13]

During assessment, the nurse may observe a lesion on the newborn’s scalp as a result of trauma from a scalp electrode placed during delivery. This finding should be documented, and the nurse should ensure the area is kept clean to prevent the development of an infection. Facial bruising may also be noted in the newborn who is large or experienced a rapid or difficult delivery. It is important to distinguish bruising from cyanosis by comparing the color of the face to other areas of the body.

See Stanford Medicine’s image of a newborn with facial bruising.

Eyes, Ears, Nose, and Mouth

Assessment of the eyes should include position, symmetry, and appearance of the conjunctiva, sclera, and eyelids. Both the sclera and conjunctiva should be clear and free of signs of infection. Subconjunctival hemorrhage, or broken blood vessels, may be noted due to the pressure of delivery; however, they are benign and should resolve in the days and weeks following birth. Swelling of the eyelids may be observed but should also resolve within days.[14]

The ears are observed for size, shape, and position. Ears should not appear low set and should be free of preauricular pits or tags. Ears are considered low set when the top of the ear sits lower than the outer corners of the eyes. Low-set ears may be a sign of congenital abnormality.[15]

Preauricular pits or tags may be noted in front of the ear and should be documented as they may be associated with some genetic conditions. A pit is a pocket or fistula, and a tag is a small bump of skin or cartilage.[16]

See Stanford Medicine’s image of a newborn with low-set ears.

See Stanford Medicine’s image of a newborn with preauricular tag.

Patency of the nose should be assessed through observation. Further evaluation may be warranted if choanal atresia is suspected, in which one or both of the nasal airways are blocked or narrowed. Some nasal congestion may be noted in the newborn; however, there should be no nasal flaring or increased work of breathing.

Milia, tiny white bumps or cysts, may be noted on the newborn, especially on their face. Milia are benign findings of dead skin cells trapped in the skin. Parents should be reassured that milia resolve in the first weeks of life. See Figure 12.10[17] for an image of milia on a newborn’s nose.

The palate of the mouth can be assessed through observation and palpation to ensure it is intact, as a cleft lip and palate are the most common anomalies seen in the head and neck of the newborn. Cleft lip and palate are further described in the “Congenital Conditions” section of this chapter.

Epstein pearls, which are white cystic vesicles similar to milia, may be seen in the newborn’s mouth. Like milia, they will resolve on their own. The tongue should move freely and symmetrically. The lingual frenulum, which normally separates before birth, should be assessed because a tight or short frenulum, known as ankyloglossia or tongue tie, may impact the newborn’s ability to effectively breastfeed.[18]

See Stanford Medicine’s image of a newborn with a tight, short lingual frenulum.

Neck and Clavicles

The newborn’s neck is short, but it should appear symmetrical with full range of motion from side to side. The clavicles should be assessed for fracture by palpating for edema or crepitus, a cracking or popping sensation noted with movement. A newborn with a fractured clavicle will often appear fussy, cry with movement of the affected arm, or limit movement of the arm. Suspicion of a fractured clavicle should be reported to the provider so additional testing can be performed.[19]

Chest

The newborn’s chest should be observed for symmetry and contour. Measurement of the chest is usually performed to determine a baseline, with the average diameter being 32 cm. The position of the nipples are normally near the midclavicular line. Supernumerary nipples may be occasionally noted, along with a protruding xiphoid process, which is a benign finding. Breast buds will appear smaller in the preterm infant. The nurse should observe the skin for color and any lesions or marks.[20]

Respiratory System

The breathing effort of the newborn should be easy. Clear and equal lung sounds should be auscultated in all fields, with a respiratory rate of 40 to 60 breaths per minute. The cry of the newborn should be lusty and vigorous.[21] When asleep, their respiratory rate may drop to as low as 30 to 40 breaths per minute. The rhythm of respirations in the newborn is often irregular with rapid breathing for a few seconds, followed by a pause for up to ten seconds, and then a resumption of breaths. This type of breathing is called periodic breathing and is a normal finding in the healthy newborn. Due to the irregularity of breathing, respirations should be counted for a full minute to ensure an accurate assessment. Periods of apnea or pauses in breathing that last longer than 20 seconds should be reported, as they may indicate respiratory problems.[22]

Transient tachypnea of the newborn (TTN) may be observed when there is a delay in clearing fluid from the lungs after birth. This delay may be more commonly seen in newborns delivered by cesarean section because they do not experience squeezing that normally occurs during delivery through the birth canal. An increased respiratory rate and crackles may be heard in the first hours of life as fluid is removed from the lungs.[23]

Nurses observe for signs of respiratory distress, including nasal flaring, grunting, intercostal retractions, tachycardia, or cyanosis.

Cardiovascular System

The normal heart rate for the newborn is 120-160 beats per minute (bpm). With activity, stress, or crying, the heart rate may rise to up to 180 bpm, but during sleep, it may drop to as low as 80 bpm. The point of maximal impulse on the newborn is at the third to fourth intercostal space of the left midclavicular line. Heart sounds should be auscultated for rate, rhythm, and quality. Benign murmurs are common in the first hours of life as fetal circulation transitions to neonatal circulation. Acrocyanosis, a bluish color of the hands and feet, is a normal finding in the first 24-48 hours as the newborn transitions to extrauterine life.

See Stanford Medicine’s image of a newborn with acrocyanosis.

Perioral cyanosis, bluish discoloration around the mouth, may be seen in the hours after birth. However, cyanosis observed in other areas, such as the chest or mucous membranes, indicates central cyanosis and requires emergency medical assistance.

See Stanford Medicine’s image of a newborn with perioral cyanosis.

Gastrointestinal System

A newborn’s abdomen is typically slightly protuberant but should be soft and free of masses. The abdomen should be observed for asymmetry, hernia, distention, or a scaphoid appearance. Distention of the abdomen may indicate an obstruction, while a scaphoid appearance may be a sign of a congenital diaphragmatic hernia, in which there is a hole in the diaphragm, allowing the organs of the abdomen to move into the newborn’s chest. A diaphragmatic hernia is an emergent finding that requires surgical intervention.[24]

Bowel sounds should be auscultated and heard in all four quadrants. The umbilical stump, which is normally white with a gelatinous appearance known as Wharton’s jelly, should be assessed for signs of infection and bleeding. The stump should also be assessed for the presence of two umbilical arteries and one vein.[25]

Diastasis recti, caused by a weakening between the two rectus abdominis muscles, may be observed but typically resolves on its own.[26] See Figure 12.11[27] for an image of diastasis recti.

Nurses assess and document the bowel and bladder function of the newborn. Normal voiding and stooling patterns are further discussed in the “Health Teaching” subsection of “Applying the Nursing Process” below. The frequency and consistency of bowel movements and voids are monitored and documented as an evaluation of feeding effectiveness, particularly in the breastfed newborn.

Musculoskeletal System

Assessment of the musculoskeletal system includes observing for symmetry of the newborn’s movement and tone in all extremities. Newborns who experienced prolonged delivery or shoulder dystocia, in which the shoulder of the newborn becomes stuck on the mother’s pubic symphysis, may exhibit signs of injury, including limited movement and expressions of pain. The extremities should move with ease and symmetry.[28]

Normally, the normal resting tone of the newborn will include flexion in their elbows and knees and adduction of their extremities to the trunk. The tightness of the adduction to the trunk decreases gradually after the first couple days of life. Tone can also be assessed while handling the newborn; they should not feel limp or floppy when held. It is important to support the head when holding newborns because they have limited strength to support and control the weight of their heads. Hypotonia, a decrease in tone, should be reported to the health care provider because it may indicate other conditions.[29]

See Stanford Medicine’s image of a newborn with hypotonia.

Newborns who were in a breech position in utero, where their buttocks enter the pelvis first instead of the head, may default to that position for the first few days.

See Stanford Medicine’s image of a newborn defaulting to the breech position during the first few days of life.

The hands and feet of newborns should be assessed for syndactyly (webbing of the toes or fingers), polydactyly (an excessive number of fingers or toes), and hip dysplasia (when the hip socket doesn’t fully cover the ball of the femur, which can cause the hip joint to partially or completely dislocate). Hip dysplasia is evaluated by a health care provider, but the nurse may notice, and report associated signs such as a difference in the length of the legs, one hip that moves differently than the other, or uneven gluteal folds.[30] See Figure 12.12[31] for an image of an infant with uneven gluteal folds indicating possible hip dysplasia.

Genitourinary System

In the term female newborn, the labia majora is prominent. A small amount of whitish discharge or blood may be noted in response to maternal hormones. It is helpful to explain this as a normal finding to parents to alleviate any concerns. The whitish discharge or blood does not need to be removed.[32]

The newborn male’s penis and scrotal sac are observed for normal development and presentation. The penis should be inspected for hypospadias (urethral placement on the underside of the penis rather than the tip). The scrotal sac is typically more pigmented than the surrounding skin and can vary greatly depending on ethnicity. Rugae, the creases over the surface of the scrotum, become more numerous and defined the closer the newborn is to term.[33]

See Stanford Medicine’s image of a newborn with hyperpigmented genitalia.

Testes should be palpated to evaluate whether they have descended into the scrotal sac and to assess for other conditions such as an inguinal hernia or hydrocele. An inguinal hernia occurs when an opening allows the bowel to extend into the scrotum and may require surgical intervention. A hydrocele is when an opening permits passage of fluid into the scrotum, but this condition typically resolves the first one to two years of life.[34]

See Stanford Medicine’s image of a newborn with a hydrocele.

If the newborn male undergoes circumcision, post-circumcision assessments are performed and documented by the nurse, including bleeding, signs of infection, and ability to urinate. These assessments are further described in the “Health Teaching” subsection below.

Neurological System

Several reflexes are present at birth that can be assessed as part of the neurologic assessment. Unless there are neurologic concerns about the newborn, assessment of a few reflexes is enough to determine neurologic status. The most commonly assessed reflexes include the rooting, suck, grasp, and Moro reflexes. Other reflexes will be discussed briefly in this section but may not be included in the assessment of the healthy newborn based on agency policy.[35]

View a supplementary YouTube video[36] from RegisteredNurseRN on newborn reflexes: Newborn Reflexes Assessment (Infant) Nursing Pediatric NLCEX Review.

Rooting Reflex

The rooting reflex helps the newborn prepare for feeding and is elicited by stroking the newborn’s cheek with a finger or nipple. The newborn should respond by turning its head toward the side that was stroked and opening its mouth. This reflex is normally present until about four months of age.[37]

Suck Reflex

The suck reflex is critical for effective feeding. It begins to be developed at 32 weeks’ gestation and is not completely intact until about 36 weeks of gestation. This reflex can be tested by putting a gloved finger or pacifier in the newborn’s mouth and assessing the strength and coordination of the suck. In the term newborn, the suck should feel rhythmic and strong, as the nurse feels resistance to removing the pacifier or finger from the mouth. Preterm infants may have difficulty feeding effectively until the reflex is fully developed around 36 weeks’ gestation.[38]

Palmar and Plantar Grasp Reflexes

The palmar grasp reflex can be observed when an object, such as a finger, is placed in the palm of the newborn’s hand, eliciting a response of flexion and grasping of the fingers. This reflex usually disappears around five to six months of age. See Figure 12.13[39] for an image of palmar grasp reflex.

The plantar grasp reflex is similar to the palmar grasp reflex, except the toes curl under when the plantar surface of the foot is pressed. The Babinski reflex is a normal reflex in infants and children up to two years old and occurs when the sole of the foot is firmly stroked from the heel to the toes, causing the big toe to bend back toward the top of the foot and the other toes to fan out. The reflex may disappear as early as 12 months.[40]

View a supplementary Open RN YouTube video[41] demonstrating the palmar grasp: ARISE Newborn Hand Grasp Reflex – Newborn Nursing Level 1.

Moro Reflex

The Moro reflex, also known as the startle reflex, occurs when the newborn is startled by a loud sound or sudden movement and responds by extending its fingers, arms, and legs. To elicit the reflex, the nurse can pull up gently on the arms of the newborn and then suddenly let go. The reflex is a response to the stimuli and may result in the newborn crying, as well as extending its arms and legs. This reflex is observed in the newborn until about two months of age.[42] See Figure 12.14[43] for an image of the Moro reflex.

View a supplementary YouTube video[44] on the Moro reflex from RegisteredNurseRN: Moro Reflex Newborn Test | Startle Reflex | Pediatric Nursing Assessment.

Stepping Reflex

Although infrequently assessed, the stepping reflex is observed when holding the newborn under the arms while letting the soles of the feet touch a surface. In response, the newborn will put one foot in front of the other as though walking. This reflex will reappear near the end of the first year as the infant prepares to learn to walk.[45]

View a supplementary Open RN video[46] of the stepping reflex: ARISE Newborn Stepping Reflex – Newborn Nursing Level 1 – 731.

Tonic Neck Reflex

The tonic neck reflex, also referred to as the fencing position, is initiated when the head of the newborn is turned to one side. In response, the arm and leg on the same side will stretch out while the arm and leg on the opposite side bends at the elbow. This reflex lasts until about five to seven months of age. See Figure 12.15[47] for an image of the tonic neck reflex.

Integumentary System

There are several integumentary findings that are specific to the newborn. Nurses should identify normal newborn findings and recognize those that require reporting to the health care provider for further evaluation.

Immediately after delivery, the skin color of the newborn is assessed as part of Apgar scoring at one minute and five minutes. Typically, the skin color is pink with cyanosis of the extremities, known as acrocyanosis, as they transition from fetal circulation to neonatal circulation. Explaining acrocyanosis to the parents can help alleviate concerns they may have regarding this normal finding in the first couple days of life. If the newborn’s skin color is pale or cyanotic in central areas of the body, actions should be taken to improve oxygenation and perfusion.[48]

Bruising or petechiae may be noted in the newborn as a result of pressure exerted during delivery. Their location and size should be documented to monitor for changes.

Vernix caseosa, often simply referred to as vernix, is a cheese-like substance that covers the skin of the newborn and protects their sensitive skin in utero from prolonged exposure to amniotic fluid. The coating of vernix assists with in-utero thermoregulation and acts as a lubricant during a vaginal birth. Delaying the newborn’s first bath allows the vernix to continue to protect the skin by keeping it hydrated.[49] See Figure 12.16[50] for an image of vernix.

Soft, fine hair known as lanugo may be observed on the newborn’s scalp, back, shoulders, forehead, and face. This hair helps to protect and keep the fetus warm in utero and usually disappears during the first weeks of life. The amount of lanugo may be more pronounced in premature infants.[51] See Figure 12.17[52] for an image of lanugo.

Erythema toxicum is a common rash of flesh-colored papules that contain eosinophils. The rash is often distributed on the newborn’s face and trunk, appearing in the first days following delivery and resolving within the first week of life.

See Stanford Medicine’s image of a newborn with erythema toxicum.

Congenital dermal melanocytosis (CDM), formerly known as Mongolian spots, are bluish discolorations of the skin commonly seen in newborns of African American, Native American, and Hispanic descent. These spots can be up to ten centimeters in diameter, usually fading by the time the child reaches the age of four. Because these spots can be confused with bruising, it is important for nurses to document their presence when observed.[53] See Figure 12.18[54] for an image of CDM.

Nevus simplex, also called salmon patches, are pink-red areas noted as a result of stretching of the capillaries. These spots, often referred to as “stork bites,” are easily blanchable patches seen commonly on the forehead, eyelids, and nape of neck. Parents may notice the spots become darker when the child is crying. Seen more in Caucasian newborns, these patches usually fade in the first couple years of life.[55]

See Stanford Medicine’s image of a newborn with nevus simplex.

Nevus flammeus, otherwise known as a port wine stain, is a dark purple or red capillary malformation that often darkens with age and persists through life. The birthmark does not require intervention; however, if a large area of the face or neck is involved, laser surgery may be indicated cosmetically to lighten the lesion.[56] See Figure 12.19[57] for an image of nevus flammeus.

Hemangiomas are benign vascular tumors that form as a result of an increase in growth of endothelial cells on the blood vessels. These tumors can be seen at birth or may develop in the first months of life. Most often hemangiomas will decrease in size over time, with about half resolving by age five and nearly all resolved by the age of ten.[58] See Figure 12.20[59] for an image of a hemangioma.

While the integumentary conditions mentioned above are considered normal variations, newborns may also experience skin conditions such as atopic dermatitis (eczema), candidiasis (thrush), or cradle cap. Atopic dermatitis (also known as eczema) is dry itchy skin that develops a rash when it is scratched or rubbed. It is prone to infection and chronic. Atopic dermatitis occurs in clients with a family history of eczema, asthma, or allergies. Environmental irritants such as detergents and allergens, as well as stress, can exacerbate this condition. Nurses can teach parents to avoid allergens, detergents, fragrances, and irritants, including rough fabrics, and to wash clothes in free and clear type detergents or those made specifically for babies. Nurses can also teach parents to apply ointments for skin hydration.[60]

Candidiasis (also known as thrush) can occur in newborns’ mouths, appearing as whitish-grey patches. Candida can naturally occur; however, sometimes newborns’ still-developing immune system cannot prevent the overgrowth of yeast. Infants and mothers can pass it to each other during breastfeeding. On the mother, it appears as red, painful nipples. In the newborn’s diaper area, candidiasis can appear as red, shiny skin and tiny red spots. It may clear up on its own or clients may need antifungal medication. Parents should clean bottle nipples and pacifiers in hot water between uses.[61]

Seborrheic dermatitis (also known as cradle cap) is an oily rash on the head, appearing as thick yellow scales on the scalp and redness on the face, neck, and behind the ears. Parents can treat cradle cap by washing the hair every other day with mild baby shampoo and loosening scales with a baby comb or brush. Parents can apply coconut oil, petroleum jelly, or mineral oil to tough scales and leave in place overnight. Parents should not otherwise pick at the scales because it could cause an infection.[62]

Laboratory and Diagnostic Tests

Newborn Screening Program

Several screening tests are performed during the newborn period to identify severe congenital conditions that can cause disability or death if left untreated. The Newborn Screening Program is a public health program that involves taking a few drops of blood from the baby’s heel shortly after birth, ideally within the first 24 hours of life but no later than three days after delivery. The samples are then sent to newborn screening centers.[63],[64] See Figure 12.21[65] for an image of collecting newborn screening samples.

Screening varies by state. Although there are national recommendations for newborn screening, it is up to each state to decide which tests to include. Nurses are often responsible for performing these screening tests, and they should be familiar with the rationale so health teaching can be provided to the parents. Newborn screenings are completed because clients may be asymptomatic at birth and if untreated, the diseases can cause serious damage. If detected early, the diseases can be treated and potential health problems minimized.

Newborn screening includes tests for the following[66],[67]:

- Metabolic problems: Metabolism converts food into energy the body can use to move, think, and grow. Enzymes are special proteins that help with metabolism by speeding up the chemical reactions in cells. Most metabolic problems happen when certain enzymes are missing or not working as they should, such as phenylketonuria (PKU).

- Hormone problems: Hormone problems in newborn screening may include congenital hypothyroidism and congenital adrenal hyperplasia.

- Hemoglobin problems: Hemoglobin carries oxygen throughout the body. Some of the hemoglobin problems included in newborn screening are sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait, hemoglobin SC disease, and beta thalassemia.

- Other problems: Other rare but serious medical problems that may be included in newborn screening include conditions such as cystic fibrosis, severe combined immunodeficiency (SCID), and spinal muscle atrophy.

Most states also screen for hearing loss and critical congenital heart disease.

Hearing Screening

Hearing screening is typically performed before the newborn is discharged from the hospital. Hearing loss in a young child can significantly impact their development, including their ability to speak and understand language. Approximately three of every 1,000 children born in the US are born with hearing loss in one or both ears.[68] Early detection of hearing loss allows for interventions that can limit the impact of the hearing deficit. In the first days of life, a newborn’s hearing should be tested using either Automated Auditory Brainstem Response (ABR) or Otoacoustic Emissions (OAE) testing equipment. The ABR test involves attaching painless electrodes to the newborn’s head while they wear small earphones to test the auditory nerve and brain stem. The OAE test involves placement of a small earphone into the newborn’s ear canal to measure an echo response to sounds that are played. The nurse performs hearing screening prior to discharge from the hospital based on agency policy. If performed too early after birth, testing can result in false positive results, so it is recommended that screening takes place as close to discharge as possible. See Figure 12.22[69] for an image of a hearing screening using otoacoustic emissions testing equipment. Newborns who do not pass hearing screening tests are referred to an audiologist for follow-up testing.[70]

Critical Congenital Heart Defects Screening

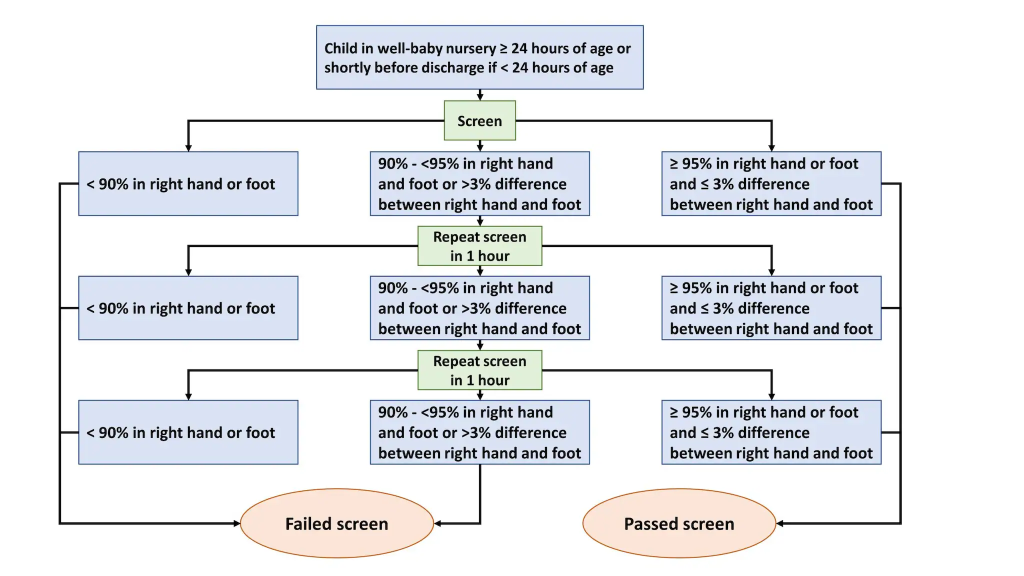

A critical congenital heart defect (critical CHD) causes hypoxia that requires surgery in the first year of life. Examples of critical CHD include coarctation of the aorta or tetralogy of Fallot. Newborns with critical CHD may appear healthy in the first days of life and not exhibit symptoms until after they are discharged home, where they can develop distress requiring emergency care. Critical CHD screening using pulse oximetry reduces early infant deaths from critical CHD by 33%.[71]

Screening for critical CHD is a quick and simple test that can be performed at the newborn’s bedside. Using a pulse oximeter, the nurse monitors the newborn’s oxygen saturation levels in the right hand and right foot and compares the difference between the two readings. If the newborn’s pulse oximeter reading is above 95% and there is less than or equal to 3% difference between the two extremities, the screening test is considered passed. If these criteria are not met, additional screening may be required to determine if the screening has been passed or failed, as outlined in the algorithm in Figure 12.23.[72],[73]

Blood Glucose

Blood glucose testing may be performed for newborns at risk for hypoglycemia, such those born to a mother with preeclampsia or diabetes, or those who are pre-term, small or large for gestational age, not feeding well, or experiencing hypothermia. The capillary blood sample is obtained from the heel of the newborn.[74]

When performing blood glucose testing, the nurse is aware that the newborn typically experiences an asymptomatic drop in blood glucose for a few hours after birth. Early, effective feeding helps stabilize and maintain the blood glucose level in the following hours and days.

Interventions for hypoglycemia are based on agency policy and determined by the age of the newborn, risk factors, blood glucose level, and symptoms. Review information about hypoglycemia in the “Common Complications During the Neonatal Period” section.

Transcutaneous Bilirubin Screening

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, transcutaneous bilirubin levels should be obtained on all newborns between 24 and 48 hours of age prior to discharge from the hospital and for newborns who have jaundice in the first 24 hours of life. The transcutaneous bilirubinometer is a noninvasive, portable, pain-free device that estimates the newborn’s bilirubin level through a probe placed on the forehead or chest. Readings are interpreted using the “BiliTool” discussed under the “Hyperbilirubinemia and Jaundice” subsection of the “Common Complications During the Neonatal Period” section.[75]

Cord Blood Sampling

Obtaining blood from the umbilical cord of the newborn is a noninvasive method of blood testing during the immediate newborn period. Cord blood sampling is commonly used to determine the newborn’s blood type and Rh factor, especially if their mother has Type O or Rh-negative blood.[76]

If an Rh or ABO incompatibility exists with the mother, the cord blood can also be tested for the presence of the mother’s antibodies, called the Coomb’s test. The Coomb’s test can be either direct or indirect. The direct test detects antibodies attached to red blood cells, while the indirect test assesses for antibodies floating in the blood. When a newborn has a positive Coomb’s test, they are at higher risk of developing jaundice requiring treatment. Review information about Rh and ABO incompatibilities under the “Hyperbilirubinemia and Jaundice” subsection of the “Common Complications During the Neonatal Period” section.

Cord blood sampling may also be used to perform a blood culture if an infection is suspected or to obtain a complete blood count (CBC).[77]

Diagnosis (Analyze Cues)

After a newborn assessment is completed, relevant cues are recognized and analyzed, and nursing problems (diagnoses) are identified. See Table 12.5d for common nursing diagnoses related to newborn care.

Table 12.5d. Nursing Diagnoses Related to Newborn Care[78]

| NANDA Nursing Diagnoses | Definition | Selected Defining Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Inadequate Nutritional Intake | Insufficient nutrient consumption to meet metabolic needs |

|

| Readiness for Enhanced Chestfeeding | Pattern of providing human milk to an infant or child, which can be strengthened |

|

| Decreased Neonatal Body Temperature | Unintended drop in the thermal state below the normal diurnal range in individuals up to 28 days of life |

Axillary temperature 36-36.4 C, decreased blood glucose level, decreased peripheral perfusion, increased oxygen demand, pallor, tachycardia, tachypnea, weight gain less than 30 g/day

Axillary temperature 32-35.9 C, acrocyanosis, bradycardia, dyspnea, grunting, inadequate energy to maintain sucking, irritable crying, lethargy, metabolic acidosis, skin cool to touch, slow capillary refill, unaddressed hypoglycemia

Axillary temperature less than 32 C, hypoxia, peripheral vasoconstriction, respiratory distress |

| Neonatal Hyperbilirubinemia | Accumulation of unconjugated bilirubin in the circulation above the 95th percentile for age during the first week of life |

|

| Readiness for Enhanced Childbearing Process | Pattern for preparing for and maintaining a healthy pregnancy, childbirth process, and care of the newborn for ensuring well-being which can be strengthened |

Desires to enhance attachment behavior, baby care techniques, baby feeding techniques, breast care, environmental safety for the baby |

Outcome Identification (Generate Solutions)

Goals for newborn care depend on their identified nursing diagnoses and specific situation. Outcome criteria are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time oriented. Sample SMART goals related to newborn care are as follows:

- The newborn will maintain a core body temperature between 97.7-99.5°F (36.5°- 37.5°C) through the course of the hospital stay.

- Prior to discharge, the newborn will demonstrate adequate intake while breastfeeding.

- The newborn will lose no more than 7% body weight during the first three days of life.

- The newborn will have at least two wet diapers in a 24-hour period and six or more wet diapers daily by Day 5.

- The newborn’s bilirubin level will remain below the level requiring intervention during the course of the hospital stay.

Implementation (Take Action)

Safety

Security of the newborn in a hospital setting is also a priority issue. Security bands are placed immediately after birth on parents and the newborn, and an embedded security alarm is placed on the infant’s umbilical stump or ankle. These security measures prevent accidental switching of newborns and also help prevent abduction from the hospital setting. Visitors may also be screened before admittance to the postpartum unit.

Common Medications and Immunizations

Nursing care in the immediate newborn period includes the administration of routine medications and immunizations to prevent complications.

Vitamin K

Newborns are born with minimal stores of vitamin K in their body, a vitamin integral for the formation of clots to prevent bleeding. A condition known as vitamin K deficiency bleeding (VKDB) can cause excessive bleeding in the newborn that can result in brain damage or death. Additionally, babies who are exclusively breastfed do not receive enough vitamin K through breast milk to reduce the risk of VKDB. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends all newborns receive an injection of vitamin K within the first six hours of life. The intramuscular injection is typically administered using a 25-gauge, 5⁄8” needle in the vastus lateralis site. Nurses must understand the rationale for administering vitamin K so they can educate parents about its importance and the risks of declining administration.[79]

Erythromycin Ointment

Newborns are at risk for a severe infection of the eye, known as gonococcal ophthalmia neonatorum. If an infant is delivered to a woman with gonorrhea, and the infection is left untreated, scarring of the cornea and blindness can occur in as little as 24 hours after birth. Due to increasing rates of gonorrheal infections in the United States, it is recommended that all newborns are treated with 0.5% erythromycin ointment administered to the eyes as soon as possible after delivery and before they are age 24 hours of life.[80],[81]

Hepatitis B

If a mother is unknowingly infected with the hepatitis B virus, it can be passed to the newborn, causing hepatitis B infection that can damage the liver and cause liver cancer. Currently, there is no cure for hepatitis B, so it is recommended that all newborns receive their first dose of the hepatitis B vaccination within the first 24 hours of life. The vaccination is administered through intramuscular injection in the vastus lateralis.

For mothers who are known to be infected with hepatitis B, the newborn will receive their first dose of the hepatitis B vaccination series, as well as the hepatitis B immune globulin (HBIG). The immune globulin provides additional protection to the newborn, allowing them to fight the virus immediately, rather than waiting for the immunity to develop from the vaccination over time.[82]

Nursing Interventions

Nurses provide interventions to term newborns during the first few days of life to facilitate the transition from intrauterine to extrauterine life.

Routine Monitoring

Routine monitoring includes the following[83]:

- Perform Apgar evaluation at one and five minutes after birth.

- Determine gestational age within two hours after birth using the Ballard Scale.

- Monitor temperature and implement interventions as indicated to maintain a core body temperature between 97.7-99.5°F (36.5°- 37.5°C).

- Monitor respiratory rate and breathing pattern. Clear secretions from oral and nasal passages as needed. Promptly report and respond to signs of respiratory distress, such as tachypnea, nasal flaring, grunting, retractions, or adventitious lung sounds.

- Monitor heart rate and skin color. Report a new murmur to the provider.

- Monitor daily weight in grams and calculate percentage of weight loss since birth.

- Monitor umbilical cord for redness and drainage.

- Monitor and document first void and stool.

- Monitor output based on the number of wet diapers and stools over a 24-hour period.

- Monitor the number of feedings over a 24-hour period. If bottle fed, document the number of ounces fed. If breastfed, document the frequency of feedings and the sides of the breasts used.

- If breastfed, assess latch and swallowing. Additional information about breastfeeding is discussed in the “Breastfeeding” subsection.

- Assess for jaundice and monitor transcutaneous bilirubin level every 8-12 hours. Report concerns to the health care provider.

- Obtain capillary blood glucose reading for infants at risk.

Routine Actions

Routine nursing interventions include the following[84]:

- Encourage skin-to-skin contact and breastfeeding as soon as possible after delivery and continue for one to two hours after birth.

- Administer vitamin K injection, erythromycin ointment, and hepatitis B vaccination.

- Perform newborn, hearing, and critical CHD screening tests per agency policy.

- Apply a stockinette cap and instruct parents to keep the newborn’s head covered to prevent heat loss.

- Swaddle the baby in a blanket to prevent heat loss and to promote a sense of security.

- Delay first bath at least 24 hours to prevent heat loss, hypoglycemia, and infant mortality.[85]

- Encourage frequent feedings and frequent diaper changes. Educate parents on stool transition expectations.

- Position newborns on their back or hold them in a reclined position after feeding and for sleeping.

- If male newborn is circumcised, apply petroleum dressing according to agency policy. Monitor for signs of bleeding.

- Make eye contact and talk to the newborn when providing care.

- Promote a quiet, soothing environment.

- Provide health teaching to parents. Health teaching topics are further discussed in the following subsection.

- Safely administer phototherapy if prescribed for jaundice.

Health Teaching

Nurses serve crucial roles to parents as educators. Instructing parents on how to care for the newborn helps to build their confidence and promotes safety for the newborn.

Breastfeeding

The choice to breastfeed is one that is often determined by cultural norms and values of the mother. Breastfeeding may also be called chestfeeding or body feeding to include clients who identify as non-binary or transgender or have a dysphoric relationship with their anatomy.[86] Breastfeeding is the preferred method of infant feeding because it reduces the risk of disease in both the mother and baby. Infants who are fed human milk are at a lower risk of developing ear and gastrointestinal infections, asthma, type 1 diabetes, obesity, and sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Mothers who breastfeed are at lower risk of developing high blood pressure, type 2 diabetes, and ovarian and breast cancer. The American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) recommends infants are exclusively fed human milk for the first six months of life and continue breastfeeding for the first year or longer. A lack of knowledge and skills is among the most common barriers to successful breastfeeding. Nurses caring for healthy newborns help establish early and effective breastfeeding when parents choose this method of feeding.[87]

Breastfeeding Basics

Nurses provide teaching on the basics of breastfeeding, including frequency of feedings, correct positioning, signs of an effective latch, and knowing if the baby is getting enough milk. Due to the small size of the newborn’s stomach and their ability to digest human milk, they need to eat often. On average, the healthy newborn will feed at the breast 8-12 times a day. The mother should be encouraged to watch for newborn feeding cues, which is their way of communicating their readiness to feed. Newborn feeding cues include the following[88]:

- Moving their fists toward their mouth

- Turning their head to look for the breast

- Appearing more alert and active

- Smacking lips or sucking on hands

- Opening and closing of the mouth

While many people think crying is the way an infant expresses hunger, crying is actually a late cue in which the infant is communicating their distress. As the mother and newborn are learning how to breastfeed, it is especially important for the mother to watch for early feeding cues because the infant is likely to be patient as the mother works to establish an effective latch during this time.

Mothers should be encouraged to initiate the feeding on the breast that feels fullest. After the baby releases itself from the nipple, the mother can burp the baby and then offer the other breast while following the lead of the newborn as to whether they are still interested in feeding.

A common concern for new mothers is wondering if their newborn is getting enough to eat. Teaching the signs of the baby being satisfied with their feeding can help alleviate this concern. When the baby is full, they typically release themselves from the breast, turn from the nipple, and appear relaxed with open fists. Indications of breastfeeding effectiveness include the baby seems satisfied after feeding, the mother’s breasts feel softer after feeding, the baby feeds at least 8-12 times in a 24-hour period, and the baby consistently has wet and soiled diapers and is gaining weight.

It is typical for the exclusively breastfed newborn to lose weight in the first days of life. However, the weight loss should not exceed 7% of the newborn’s body weight, and the weight should be regained by the tenth day of life.[89]

Correct Positioning

The nurse assists the new mother in positioning the infant during breastfeeding to ensure a proper latch, to avoid nipple trauma, and to create a comfortable experience for the mother and newborn. The following subsections describe several common breastfeeding positions. While the mother and baby may find the one that is most comfortable for them, varying positions helps prevent nipple trauma and drain most areas of the breasts.[90],[91] Draining most areas of the breasts helps prevent clogged milk ducts, which can be painful and lead to mastitis (infection of the breast’s milk ducts).[92]

Cradle Hold

The cradle hold is the most common position as it allows the mother to be supported while providing support for the newborn as well. For this hold, the mother holds the infant in her arm on the same side as the breast she is using to feed. The head of the infant will rest in the bend of the mother’s elbow. It is helpful in this position to have a chair with arms or pillows to support the mother’s arms, so she is not leaning forward but is relaxed and comfortable for the duration of the feeding. The mother uses her opposite hand to support the breast and guide it to the infant’s mouth. The newborn’s head should be in line with the body, which is facing the mother, and not turned to the side.[93],[94] See Figure 12.24[95] for an image of the cradle hold position.

Cross-Cradle Hold

When the mother feels she needs more control over the newborn’s head, she should use the cross-cradle hold. This position is particularly useful for mothers who are having difficulty obtaining a good latch because it provides for more control and visibility. For this hold, the mother lays the newborn across her abdomen and holds the newborn’s head with the opposite hand of the breast she is feeding on. With the hand on the feeding side, the mother can support the breast and guide it to the newborn’s mouth.[96],[97] See Figure 12.25[98] for an image of the cross-cradle hold.

Laid-Back or Straddle Position

This position works well for newborns and is a good way for mother and baby to get skin-to-skin contact. For this position, the mother should be reclined, but not lying flat, with the newborn laying on her abdomen. The newborn should be supported and allowed to use their instincts to find the nipple and latch.[99],[100] See Figure 12.26[101] for an illustration of the laid-back/straddle position.

Side-Lying Position

This position should be used after breastfeeding is well-established because it limits the mother’s ability to visualize the latch. The mother should be lying on her side, while supporting her back and head. With the newborn facing the breast, the mother can guide the breast to the newborn’s mouth and once latched can use the hand to support the newborn.[102],[103] See Figure 12.27[104] for an illustration of the side-lying position.

Football or Clutch Hold

The football or clutch hold is a good position for clients who are recovering from a C-section as the baby is not lying on the mother’s abdomen. This position also works well for mothers who are breastfeeding twins. In this position the newborn is held at the client’s side with their head and neck supported with the palm of the mother’s hand. The mother will use her opposite hand to support and guide the breast to the newborn’s mouth.[105],[106] See Figure 12.28[107] for an illustration of the football or clutch hold.

Obtaining a Correct Latch

Regardless of the position the mother chooses for feeding, a correct latch is crucial to the transfer of breastmilk and comfort for the mother. The nurse can teach the mother signs to look for that indicate the newborn is latched correctly to the nipple. Signs of a correct latch include the following[108],[109]:

- The latch is comfortable and pain free.

- The baby’s chest and stomach rest against the mother’s body, so the baby’s head is straight, not turned to the side.

- The baby’s chin touches the breast.

- The baby’s mouth opens wide around the areola, not just the nipple.

- The baby’s lips turn out.

- The baby’s tongue cups under the breast.

- You hear or see the baby swallowing.

- The baby’s ears move slightly.

- The baby’s lower lip covers more of the areola than the upper lip, pointing the nipple toward the roof of the newborn’s mouth.

If the mother is experiencing pain with latching, the nurse must intervene early to prevent damage to the nipple, as well as to minimize frustration or fear with breastfeeding. Many birthing facilities employ lactation specialists who work closely with new mothers to help them establish comfortable and effective breastfeeding. Many communities also provide resources to support breastfeeding mothers, such as the La Leche League. The nurse should share information about these types of resources to support the mother and baby in successfully breastfeeding.

Read more about breastfeeding basics from at the WIC Breastfeeding Support web page.

Bottle Feeding

Bottles can be used to feed newborns expressed human milk or infant formula. Ensuring the feeding items are clean is critical to making sure the newborn is fed safety. Bottles should be cleaned after each feeding, paying particular attention to the individual parts of the bottle, including the nipples or rings. If possible, items should be washed in a dishwasher using a heated drying or sanitization setting. When a dishwasher is not available, items can be hand-washed in a basin with hot water and soap. A basin and clean brush should be designated for cleaning bottles and not used to clean other items. The bottle and its parts should be washed and rinsed well and allowed to air dry.[110]

Parents should be instructed on how to correctly prepare infant formula, keeping in mind it may come in ready-to-feed, concentrated, or powdered preparations. Each requires different steps for safe preparation. Parents should follow the instructions provided on the packaging for whatever preparation they use. Using the correct amount of water is vital because using too little water results in a concentrated formula that can harm the newborn’s kidneys and digestive system, and using too much water dilutes the formula and does not provide adequate nutrition. While infant formula does not require warming, many parents warm the formula. Parents should know that expressed human milk and infant formula should never be warmed in the microwave because it can result in uneven heating and potentially burn the newborn’s mouth and throat.

Newborns typically eat one to two ounces of infant formula at each feeding. Similar to breastfed newborns, formula-fed newborns should eat every two to three hours. As the infant grows, they will consume more formula at each feeding and will gradually increase the time between feedings. Parents should be instructed to watch for signs of hunger, as well as signs of fullness, and not force the newborn to finish the contents of a bottle. Allowing the newborn to stop drinking when they indicate they are done helps them learn they can regulate their own intake. This helps them learn a healthy relationship with food, decreasing the chance of childhood obesity and digestive problems. Formula should be prepared in the amount needed for a feeding and consumed within two hours of its preparation. Any leftover formula should be discarded after the feeding because bacteria can grow as a result of the formula mixing with the newborn’s saliva.[111],[112]

Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) is a federally funded nutrition program that provides education on healthy foods, breastfeeding support, and nutrition at no cost. Nurses should be aware of local community resources available to support mothers and infants to ensure adequate nutrition.

Visit the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Food and Nutrition Service web page to learn more: Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC).

Normal Voiding and Stool Patterns

New parents are often concerned about their newborns getting enough to eat. A good way to alleviate this concern is to teach them about the normal voiding and stooling patterns of the newborn. If a newborn is receiving adequate intake, they consistently void and have bowel movements.

The newborn’s first stools are greenish-black and sticky, known as meconium. This first stool typically occurs in the first 24-48 hours of life. In the first few days, newborns usually have one to two stools per day, and by one week of age, they typically have five to ten stools a day and have a bowel movement with each feeding. With consistent feedings, the newborn’s stool will transition from meconium to yellow or yellowish-brown. Breastfed babies tend to have stools that are more yellow in color, look seedy in consistency, or may be runny or pasty. Their stools also tend to be sweeter smelling and less odorous than that of formula-fed newborns. Frequency of stools may decrease as the newborn reaches the end of the first month of life.[113]

View Stanford Medicine’s image of meconium.

Newborns typically void within the first 24 hours of life. In the first days, urine may be orange, pinkish, or chalky, which indicate urate crystals, as the urine is concentrated until the newborn establishes adequate intake. The number of wet diapers will increase each day, and by the fifth day, the newborn should have six to ten wet diapers a day. The parents can be encouraged to keep track of soiled and wet diapers to reassure them the newborn is eating enough and alert them of feeding issues.[114]

View Stanford Medicine’s image of urate crystals.

Bathing

Delaying the newborn’s first bath at least 24 hours has become standard practice in many hospitals in the United States because it has been shown to reduce the risk for hypothermia and increase exclusive breastfeeding rates. There is some debate yet about whether a newborn should be given a sponge bath until their umbilical stump falls off or if an immersion bath is appropriate. Some research shows that immersion bathing does not delay the drying of the umbilical stump and, therefore, is recommended, as it results in less loss of heat in the newborn. Parents are instructed to perform either option based on their health care provider’s recommendation. Nurses should be aware of agency and health care providers’ recommendations to ensure clear and consistent instruction is provided. Nurses also consider religious and cultural preferences of the family because they may have specific beliefs and values about the frequency and timing of bathing.[115]

Bathing is an opportunity for parents to bond with the newborn. Parents are instructed about evidence-based guidelines for bathing newborns. Newborns should not be bathed on a daily basis as this can cause their skin to become dry. The diaper area should be cleaned when soiled, and the skin should be cleansed if the newborn spits up. An infant only requires a full bath every few days with shampooing necessary just once a week. Steps should be taken to ensure the newborn does not lose a significant amount of heat during the bathing process. Having supplies readily available and the water warmed appropriately can limit the bathtime and risk for hypothermia. Due to the potential sensitivity of the newborn’s skin, it is best to use a gentle cleanser, making sure all cleanser is rinsed well from the skin.[116]

When giving the newborn a sponge bath, the nurse should instruct the parents in the following basic steps:

- Use a warm, flat surface such as the kitchen counter or changing table.

- Fill a basin or sink with lukewarm water (around 100 degrees F). Parents should also be instructed to set their water heater below 120 degrees F to reduce the risk for burns.

- Gather all needed supplies prior to the bath, including the basin, washcloths, cleanser, and towels so the newborn is not left unattended.

- Undress the newborn and wrap them in a towel.

- Lay the newborn on a clean, dry towel.

- To reduce heat loss, only expose the body part that is being cleansed.

- Start by cleaning the face without cleanser and wiping the eyelids from inner to outer corner.

- Clean the other areas of the body with soap and water and be sure to rinse the skin well.

- Pay particular attention to folds under the neck, arms, and thighs.

- Save the diaper area for last.

After the newborn’s umbilical stump has fallen off, the newborn can be bathed in a plastic bathtub or sink. When bathing in a tub, the same principles apply relating to the temperature of the water and ensuring supplies are nearby so the newborn is not left unattended.

Umbilical Cord Care

Immediately after delivery, the cord is clamped and then cut, leaving a short stump on the newborn’s umbilicus.

View Stanford Medicine’s image of a clamped umbilical cord stump.

The stump dries and then falls off on its own within one to three weeks of life. See Figure 12.29[117] for an image of a drying umbilical cord in a newborn. Parents should be instructed to keep the stump dry and exposed to air by folding the front of the diaper down during diaper changes. While care of the umbilical stump has changed over the years, current best practice is to allow it to dry and fall off on its own. Parents should be discouraged from applying rubbing alcohol or ointments to the stump and should sponge bathe the newborn or provide a quick submersion bath until the cord falls off. If parents notice blood-tinged or clear drainage from the site, they should be instructed to wipe the area clean with a damp cotton ball and then dry the area. It may be necessary to push down on the skin around the stump or slightly bend the stump to get to the drainage. The stump may change color as it dries, and the parents may notice a small amount of bleeding if the stump gets caught on the diaper or when the stump falls off. Most umbilical stumps dry and fall off with ease; however, parents should be taught when to call the provider. Signs that require provider notification include increased bleeding from the stump or a small amount that continues beyond three days; thick, yellow drainage; a warm, swollen, or reddened area around the umbilicus; or a foul smell from the area. Parents should also contact the provider if the stump has not fallen off by three weeks of age.[118]

Circumcision Care

Circumcision is a surgical procedure in which the foreskin, the layer of skin that covers the head of the penis, is removed. While routine circumcision is not recommended by the American Academy of Pediatrics because it is not essential for well-being, the benefits outweigh the risks to justify having it available. Parents may choose to have their male newborn circumcised due to personal, religious, or cultural preferences. The procedure is often performed in the hospital prior to being discharged home, so nurses instruct parents on how to care for the surgical site.

There are three common techniques for the circumcision procedure, including use of the Mogen clamp, Gomco clamp, or Plastibell device, and post-procedure care is similar for all techniques. Parents should be instructed to clean and apply petroleum-infused gauze on the site with each diaper change. A small amount of yellow fluid may be noted as the site is healing. Parents should be instructed the drainage is a normal sign of healing and should expect the circumcision to be completely healed within seven to ten days.[119]

Parents should be instructed to call the health care provider about the following conditions related to healing of the circumcision site:

- Pain is not relieved with the pain medication provided

- Temperature greater than 101° F

- Bleeding more than a couple drops on the penis or diaper

- Yellow-green drainage or foul odor

- Decreased number of wet diapers

- If a Plastibell ring was used, it falls off prior to three days, stays on more than ten days, or it slips below the head of the penis

- Blue or black color on the head of the penis

Sleep-Related Death Prevention

According to the American Academy of Pediatrics, 3,500 infants die every year due to sleep-related deaths, including sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). Under the umbrella term called sudden unexplained infant death (SUID), SIDS is the death of an infant that cannot be explained through investigation, autopsy, or review of clinical history. The pathophysiology of SIDS is multifactorial; however, several recommendations related to safe sleeping have been shown to decrease the risk[120]:

- Position babies on their backs for sleeping.

- Use a firm, flat, non-inclined sleep surface to reduce the risk of suffocation or wedging/entrapment.

- Feed newborns human milk.

- For the first six months, infants should sleep in their parents’ room close to the bed but on a separate surface designed for infants.

- Soft objects, such as pillows, pillow-like toys, quilts, comforters, mattress toppers, or fur-like materials, and loose bedding, such as blankets and non-fitted sheets, should not be used in the infant’s sleep area to reduce the risk of SIDS, suffocation, entrapment/wedging, and strangulation.

- Offering a pacifier at naptime and bedtime.

- Smoking and nicotine exposure should be avoided by the mother during pregnancy and after birth. Avoid exposing infants to second-hand smoke.[121]

- Alcohol, marijuana, opioids, and illicit drug use should be avoided by the mother during pregnancy and after birth.

- Avoid overheating.

- Infants should be immunized according to current guidelines from the AAP and CDC.

- Home cardiorespiratory monitors should not be used as a strategy to reduce the risk of SIDS.

- Infants should be placed in supervised tummy time while awake for short periods of time to develop their neck, shoulder, and arm muscles and preserve full head shape beginning soon after hospital discharge and increasing incrementally to at least 15 to 30 minutes daily by seven weeks of age.

Nurses should keep up-to-date with current recommendations to prevent SIDS and teach and model these recommendations when providing newborn care.

Car Seat Safety

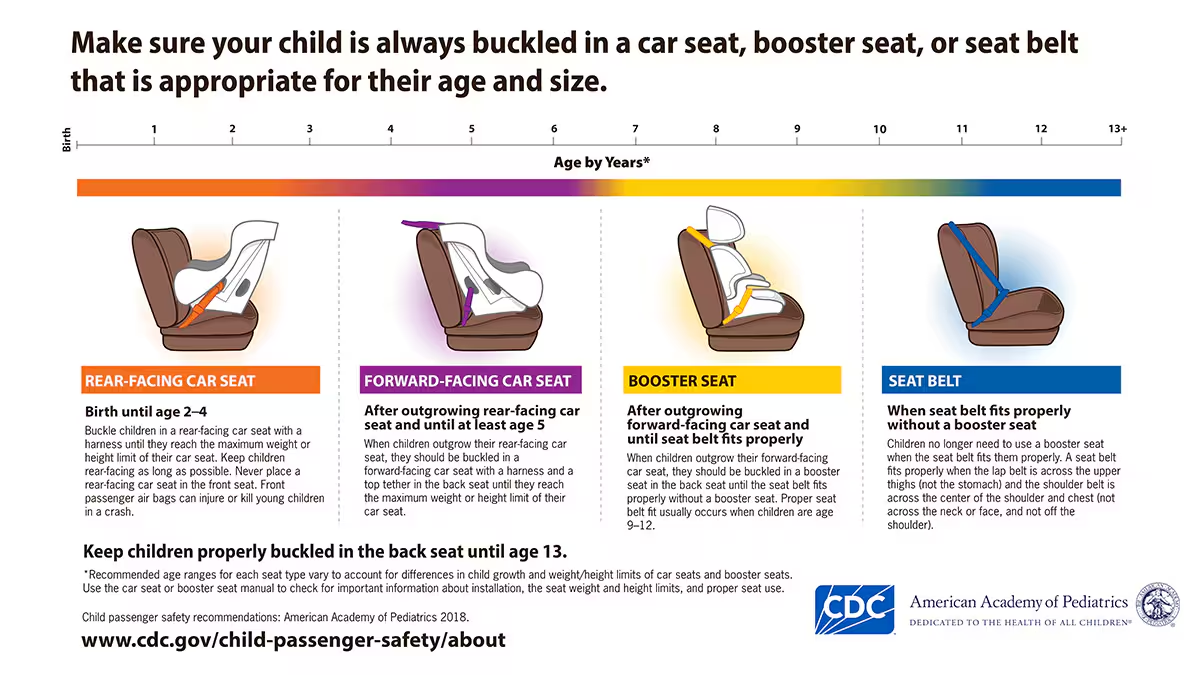

According to the National Highway Transportation and Safety Administration (NHTSA), crashes are the leading cause of death in children from ages 1 to 13.[122] Parents should ensure they have the correct car seat and are using it appropriately to reduce the risk of their child’s death in a car accident. There are a variety of car seats and vehicles, so parents should read the car seat installation instructions and review their owner’s manual for information on car seat installation specific to their vehicle. For example, some vehicles have LATCH anchor systems that can be used in place of the seat belt.

When providing information on car seat safety for a healthy newborn, nurses should educate parents that infants should only be placed in a rear-facing seat for the first year of life. A rear-facing seat provides the needed protection for the infant’s fragile neck and spine. The middle of the back seat is considered the safest position for a car seat, as long as the seat can be secured tightly using the seat belt or anchor system. Nurses can refer parents to Child Passenger Safety Technicians (CPST) in their area who are specifically trained in installing car seats.[123] See Figure 12.30[124] for an illustration about car seat recommendations.

View the NHTSA recommendations PDF about car seat safety.

Soothing a Crying Infant

Infants cry to communicate, and parents can find it distressing when they can’t figure out how to help. Nurses play an important role in helping parents learn to soothe their newborn with the hope the infant will learn to self-soothe eventually by teaching the following information[125]:

- The first step is to teach parents reasons a newborn might cry. They may be hungry, tired, uncomfortable, bored, overstimulated, or have a dirty or wet diaper.

- If it has been two hours since feeding, they may be hungry. Parents can detect hunger cues and feed before the infant starts crying. These hints are fussing, lip smacking, bringing the hand to the mouth, and chewing on hands.

- Babies need to burp while feeding because they swallow air. The air exerts pressure, which can be uncomfortable. If the newborn cries after eating, they may need to burp. Parents can help a baby burp by patting the back, bouncing them in an upright position, or laying the infant in a prone position. While feeding, parents should burp the infant after one breast is emptied or after a formula-fed infant drinks one to one-and-a-half ounces.

- If it has been two hours since sleeping, they may be tired. Cues showing the baby may be tired are red puffy eyes, rubbing eyes, or yawning. If parents can intervene before the baby starts crying, they may be able to fall asleep more easily than if the infant gets agitated.

- Babies may cry if they are bored or overstimulated, and each baby’s response to the environment is different. A baby who cries from boredom might like being in a front-carrier on the parent or participating in activities. On the other hand, some babies find people, lights, and sounds overstimulating. If the baby needs a break from this, they might feel comfort from swaddling and a quiet place.

- Babies may cry if they are too hot or too cold and will need help regulating their temperature with clothing and environmental temperature. In general, babies need one more layer of clothing than adults wear.

Community Resources

Numerous community resources are focused on supporting newborns and families, such as Women, Infants, and Children (WIC); Healthy Start; Early Steps; A Safe Haven for Newborns; La Leche League; and Kelly Mom. These agencies are provided in the following box. Nurses should also familiarize themselves with local community resources available to support the newborn and their family.

Resources

Here are helpful resources for newborns and their families:

- Women, Infants, and Children (WIC): https://www.fns.usda.gov/wic

- Wisconsin WIC: https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/wic/index.htm

- Healthy Start: https://www.nationalhealthystart.org/

- A Safe Haven for Newborns: https://asafehavenfornewborns.com/

- La Leche League: https://llli.org/

- Kelly Mom: https://kellymom.com/

Evaluation (Evaluate Outcomes)

Nurses evaluate the effectiveness of interventions to determine if outcome criteria have been met, partially met, or not met. For example, nurses commonly evaluate the number of wet diapers and stools to assess a newborn’s nutritional intake. The nursing care plan is revised as needed to effectively meet the established outcome criteria.

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. (2022). Apgar score. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003402.htm ↵

- MedlinePlus [Internet]. (2022). Apgar score. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003402.htm ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2016, December 31). APGAR newborn assessment score scale test made easy w/ NCLEX practice questions [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Used with Permission. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cQKaTCMFjwc ↵

- Perinatology.com. (2024). Ballard score calculator. https://www.perinatology.com/calculators/Ballard.htm ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part I. General, head and neck, cardiopulmonary. American Family Physician, 90(5), 289-296. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p289.html ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part I. General, head and neck, cardiopulmonary. American Family Physician, 90(5), 289-296. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p289.html ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part I. General, head and neck, cardiopulmonary. American Family Physician, 90(5), 289-296. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p289.html ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part I. General, head and neck, cardiopulmonary. American Family Physician, 90(5), 289-296. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p289.html ↵

- Lipsett, B. J., Reddy, V., & Steanson, K. (2024). Anatomy, head and neck: Fontanelles. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK542197/ ↵

- Mount Sinai. (2023). Sutures - ridged. https://www.mountsinai.org/health-library/symptoms/sutures-ridged ↵

- “702_Newborn_Skull-01.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Jacob, K. (2023). Caput succedaneum. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK574534/ ↵

- Raines, D. A. (2024). Cephalohematoma. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470192/ ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part I. General, head and neck, cardiopulmonary. American Family Physician, 90(5), 289-296. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p289.html ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part I. General, head and neck, cardiopulmonary. American Family Physician, 90(5), 289-296. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p289.html ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part I. General, head and neck, cardiopulmonary. American Family Physician, 90(5), 289-296. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p289.html ↵

- “baby-784607_1920.jpg” by Tawny Nina Botha from Pixabay is licensed under CC0 ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part I. General, head and neck, cardiopulmonary. American Family Physician, 90(5), 289-296. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p289.html ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part I. General, head and neck, cardiopulmonary. American Family Physician, 90(5), 289-296. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p289.html ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part I. General, head and neck, cardiopulmonary. American Family Physician, 90(5), 289-296. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p289.html ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part I. General, head and neck, cardiopulmonary. American Family Physician, 90(5), 289-296. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p289.html ↵

- Stanford Medicine Children’s Health. (n.d.). Breathing problems. https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=breathing-problems-90-P02666 ↵

- Jha, K. (2023). Transient tachypnea of the newborn. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK537354/ ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part II. Skin, trunk, extremities, neurologic. American Family Physician, 90(5), 297-302. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p297.html ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part II. Skin, trunk, extremities, neurologic. American Family Physician, 90(5), 297-302. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p297.html ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part II. Skin, trunk, extremities, neurologic. American Family Physician, 90(5), 297-302. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p297.html ↵

- “Hernie_ligne_blanche.JPG” by Wikigil is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part II. Skin, trunk, extremities, neurologic. American Family Physician, 90(5), 297-302. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p297.html ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part II. Skin, trunk, extremities, neurologic. American Family Physician, 90(5), 297-302. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p297.html ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part II. Skin, trunk, extremities, neurologic. American Family Physician, 90(5), 297-302. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p297.html ↵

- “1-s2.0-S1875957217302176-gr1_lrg.jpg” by unknown author is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 4.0. Access for free at https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1875957217302176#ack0010. ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part II. Skin, trunk, extremities, neurologic. American Family Physician, 90(5), 297-302. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p297.html ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part II. Skin, trunk, extremities, neurologic. American Family Physician, 90(5), 297-302. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p297.html ↵

- Lewis, M. L. (2014). A comprehensive newborn examination: Part II. Skin, trunk, extremities, neurologic. American Family Physician, 90(5), 297-302. https://www.aafp.org/pubs/afp/issues/2014/0901/p297.html ↵

- Stanford Medicine Children’s Health. (n.d.). Newborn reflexes. https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=newborn-reflexes-90-P02630 ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2020, July 27). Newborn reflexes assessment (Infant) nursing pediatric NLCEX review [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Used with permission. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=rHYk1sYsge0 ↵

- Stanford Medicine Children’s Health. (n.d.). Newborn reflexes. https://www.stanfordchildrens.org/en/topic/default?id=newborn-reflexes-90-P02630 ↵