11.5 Applying the Nursing Process and the Clinical Judgment Model to Postpartum Care

This section will apply the nursing process and the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model (NCJMM) to caring for postpartum clients. The NCJMM steps are included in parentheses after each step of the nursing process.

Assessment (Recognize Cues)

Postpartum assessment begins after the birth of the placenta and continues until the client’s discharge home. The nurse performs postpartum assessments in a systematic manner and observes for progression in healing or signs of complications. Postpartum assessment findings change slightly from the immediate postpartum period over the next 48 hours.[1]

Vital Signs

Postpartum recovery begins immediately after birth. The nurse typically assesses and documents vital signs every 15 minutes during the first hour of postpartum recovery, every 30 minutes to one hour during the second hour, and then every four hours. After the postpartum client is stable, vital sign measurements might change to every eight hours or once per shift according to health care provider orders and agency policy.

Temperature

A slight elevation in the client’s temperature may occur during the first 24 hours due to dehydration and the work of labor. After 24 hours, the client should remain afebrile. A temperature above 100.4º F (38º C) at any time indicates possible infection and should be reported to the health care provider.

Blood Pressure

Blood pressure (BP) obtained during the postpartum period should be compared to the client’s reading from the first trimester, with a spontaneous return to prepregnant normal BPs within the first few days after delivery. Orthostatic hypotension may occur due to cardiovascular changes after childbirth, so the client should be reminded to slowly move from a sitting or lying position to a standing position to prevent dizziness.

A slight increase in BP in the immediate postpartum period may occur due to pain, anxiety, and fluid shifts, resulting in increased cardiac output. However, BP greater than 140/90 mm Hg, especially when associated with headaches or visual changes, should be reported to the health care provider because they can indicate postpartum preeclampsia.

A slight decrease in BP is normal due to expected blood loss during delivery, but BP less than 100/60 mm Hg is associated with hypovolemia, resulting from postpartum hemorrhage. Hypotension should be promptly reported to the health care provider, along with any associated symptoms such as tachycardia, dizziness, and weakness.

Heart Rate

Postpartum bradycardia is common for six to ten days after delivery with rates between 50 to 70 beats per minute. Heart rate may also be elevated above a client’s baseline due to pain or mild dehydration, but a heart rate above 100 beats per minute should be reported to the health care provider. Tachycardia may indicate infection or compensation for hypovolemia, resulting from blood loss.

Respiratory Rate and Pulse Oximetry

Respiratory rate may be slightly increased from pain, but it should remain between the normal range of 12-20 breaths per minute. Abnormal findings such as tachypnea, shortness of breath, chest pain, or restlessness may indicate pulmonary edema or pulmonary emboli and should be promptly reported to the health care provider. Pulse oximetry is used to monitor oxygenation status and should remain above 95%. Hypoxia is treated with supplemental oxygen and titrated per provider orders.

Pain

Pain is considered the fifth vital sign and is assessed and managed throughout the postpartum period. Common sources of pain include uterine cramping, breast discomfort with lactation changes, perineal pain, and incisional pain if a cesarean delivery was performed. Pain is managed by the nurse with nonpharmacological and pharmacological interventions that are further discussed under the “Interventions” subsection.

Focused Postpartum Assessments

Focused postpartum assessments can be memorized using the mnemonic BUBBLE-EE:

- B: Breasts

- U: Uterus

- B: Bladder

- B: Bowels

- L: Lochia

- E: Episiotomy and perineum

- E: Extremities

- E: Emotional Status

Table 11.5a summarizes the BUBBLE-EE assessments. Each category is further discussed in the following subsections, along with health teaching that can be provided during the assessment.

Table 11.5a. BUBBLE-EE Focused Postpartum Assessments[2]

| Category | Assessments |

|---|---|

| B: Breasts |

|

| U: Uterus |

|

| B: Bladder |

|

| B: Bowels |

|

| L: Lochia |

|

| E: Episiotomy and perineum |

|

| E: Extremities |

|

| E: Emotional Status |

|

Breasts and Breastfeeding

When breasts are filling with milk, the nurse will note a slight firmness on assessment. Engorgement is expected at three to five days postpartum, causing the breasts to feel full, firm, and uncomfortable.

If the client is breastfeeding, the nurse assesses the nipples for tenderness, inversion, trauma, cracking, or blisters. The nurse also observes a breastfeeding session to assess latch.

Latch

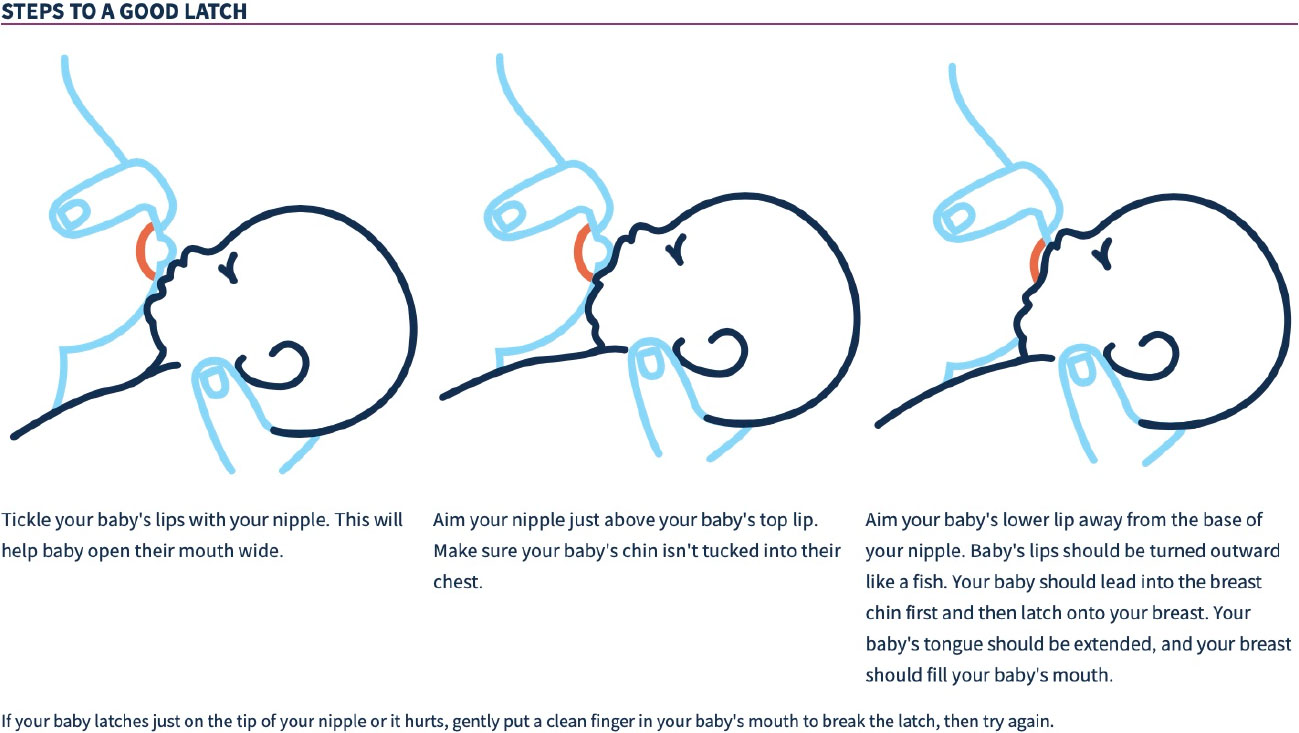

To adequately provide milk, the infant must have an effective latch. Signs of a good latch include the infant’s chest being against the mother’s chest; the infant’s head being straight and not turned to the side; the infant’s mouth being wide prior to latching; and the areola, not just the nipple, in the infant’s mouth. The client should report the nipple feeling comfortable and pain free while breastfeeding. Signs of an inadequate latch include painful, cracked nipples; nipples shaped irregularly after nursing; pain during breastfeeding; and a feeling of lack of emptying of the breast. If the ineffective latch continues, the client will eventually have inadequate milk supply.[3] See Figure 11.14[4] for an illustration of steps to obtain a good latch.

The acronym LATCH can be used to assess key areas of breastfeeding[5],[6]:

L: The infant’s ability to latch onto the breast

A: The presence of audible swallowing by the infant while feeding

T: The mother’s nipple type

C: The mother’s sense of comfort

H: The holding position used by the mother during feeding

The LATCH score helps the nurse determine if the infant is getting a good latch to avoid nipple trauma and an inadequate milk supply. See Table 11.5b for components of the LATCH score with the higher the score, the better the latch. If observations indicate ineffective latch despite health teaching and reinforcement, the nurse makes a referral to a lactation consultant for additional assistance with breastfeeding.

Table 11.5b. LATCH Score[7],[8]

| Score | 0 | 1 | 2 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Latch |

|

|

|

| Audible swallowing |

|

|

|

| Type of nipple |

|

|

|

| Comfort |

|

|

|

| Hold |

|

|

|

Review correct positions for holding the infant during breastfeeding in the “Interventions” subsection of the “Applying the Nursing Process and Clinical Judgment Model to Newborn Care” section of the “Newborn Care” chapter.

Uterus

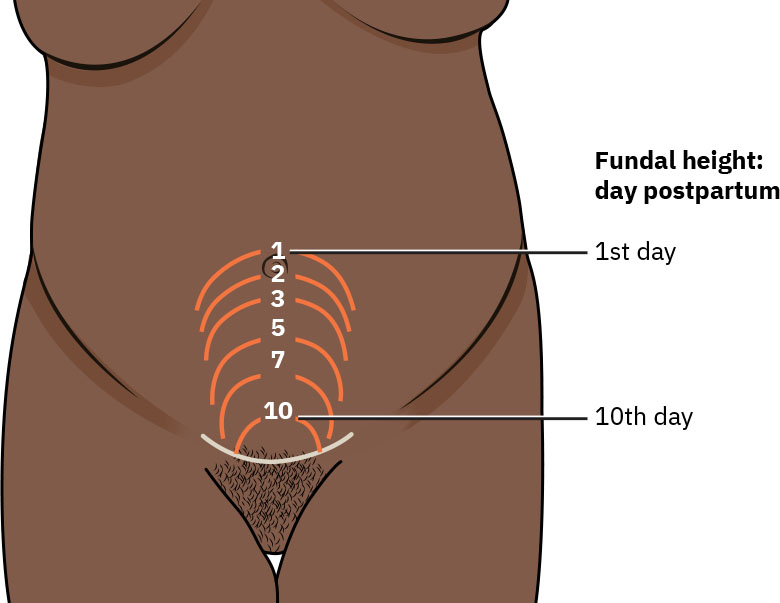

The nurse routinely assesses involution of the uterus during the postpartum period. After birth, the uterus rapidly contracts, and the fundus (top of the uterus) can be palpated in the abdominal area. Involution is the process by which the uterus returns to a nonpregnant state. Subinvolution is failure of the uterus to return to the nonpregnant state and can lead to postpartum hemorrhage. Involution may be inhibited due to several factors, such as a long labor, multiple births, retained placental tissue, or a full bladder. See Figure 11.15[9] for an illustration of subinvolution based on postpartum day.

If the client had a cesarean delivery, the nurse premedicates with an analgesic prior to the fundal assessment. Before performing the assessment, the nurse asks the client to empty their bladder because a full bladder can prevent subinvolution. To perform a fundal assessment, the nurse positions the client in a supine position and then places one hand on the fundus while the other hand supports the uterus near the symphysis pubis. The fundus should be firm, midline, and slightly above or below the umbilicus the first 24 hours after birth and then involute approximately one centimeter daily. If the fundus is boggy, deviated to one side, or elevated, the nurse encourages the client to void because a full bladder can prevent involution. Upon reassessment after voiding, if the fundus remains boggy or deviated to one side, the nurse performs fundal massage and assesses the lochia and for other signs of postpartum hemorrhage.[10]

Review information about postpartum hemorrhage and fundal massage in the “Postpartum Complications” section.

During the fundal assessment, the nurse teaches about intermittent uterine contractions that occur during the process of involution. Clients may describe these contractions as menstrual-like cramping or more severe pain that is similar to contractions during labor. The pain may be severe for the first two to three days after birth, especially for multigravida clients. The pain is also triggered by breastfeeding as oxytocin is released. The nurse explains that while uncomfortable, this pain serves an important purpose as the contractions reduce the size of the uterus to prepregnancy size and prevent excessive bleeding.

If the client had a cesarean delivery, the nurse also assesses the abdominal dressing over the incision to ensure it is clean and dry. After the surgeon removes the initial abdominal dressing, the nurse assesses the incision for approximation and for signs of infection (redness, warmth, tenderness, and drainage).

Lochia

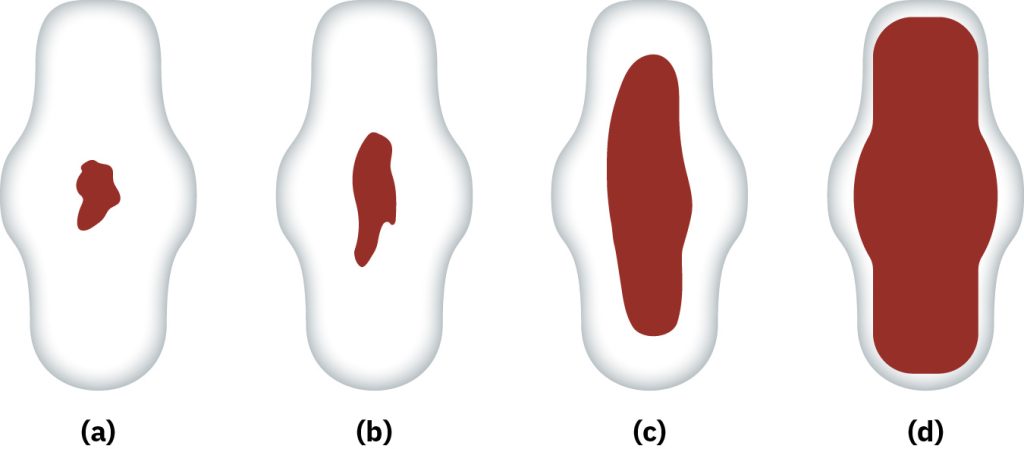

Assessing the lochia is a priority assessment as the nurse monitors for postpartum hemorrhage. Clients are typically requested to leave their used peripads in a specific area of the restroom for the nurse to assess. The nurse asks the client the last time they changed their peripad and documents the amount of lochia on the pad, its color and odor, and the presence of clots. Lochia typically has a musty odor that is normal, but malodorous lochia can indicate infection. A scant amount of lochia on the peripad is equal to or less than a 2.5-centimeter stain of lochia rubra, a small amount is less than a 10-centimeter stain, a moderate amount is equal or greater than a 10-centimeter stain, and a heavy amount saturates a peripad in one hour or includes clots larger than a golf ball. See Figure 11.16[11] for an illustration of lochia amounts. Continuous bleeding that is bright red in color may occur with lacerations but is also associated with postpartum hemorrhage and should be promptly reported to the health care provider.

Some agencies have policies for weighing the peripads for quantification of blood loss as part of their postpartum hemorrhage protocol. Using a calibrated scale, nurses weigh the soiled peripads, underpads, and linen. The dry weight of all clean materials (peripad, underpad, and linen) is subtracted from the soiled weight to obtain the weight of the lochia in grams. The weight of the lochia in grams is converted to milliliters (mL), with 1 gram equivalent to 1 mL.[12]

The nurse teaches clients about the characteristics of lochia during assessment. Table 11.5c summarizes expected findings of lochia during the postpartum period.

11.5c. Expected Lochia Findings During the Postpartum Period

| Types of Lochia | Expected Findings |

|---|---|

| Lochia rubra |

|

| Lochia serosa |

|

| Lochia alba |

|

Bladder

Postpartum diuresis causes increased urine output. However, a client may have decreased bladder tone and decreased sensation to void due to physiologic accommodations made during labor and/or the effects of epidural or spinal anesthesia. Decreased sensation or the inability to void can result in overdistension of the bladder and urinary retention. Signs of a distended bladder include the following:

- Palpation of the bladder above the symphysis pubis

- Frequent voiding of less than 150 mL urine output

- Bladder discomfort

- Fundal height above the anticipated level based on the postpartum day, displacement of the fundus away from midline, a boggy uterus, or excessive lochia

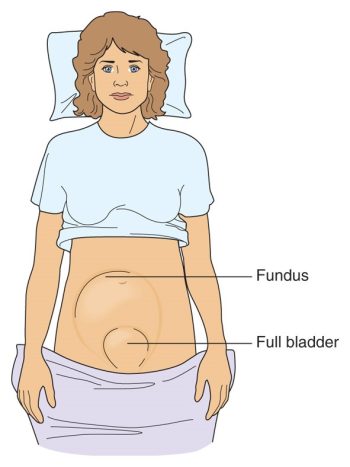

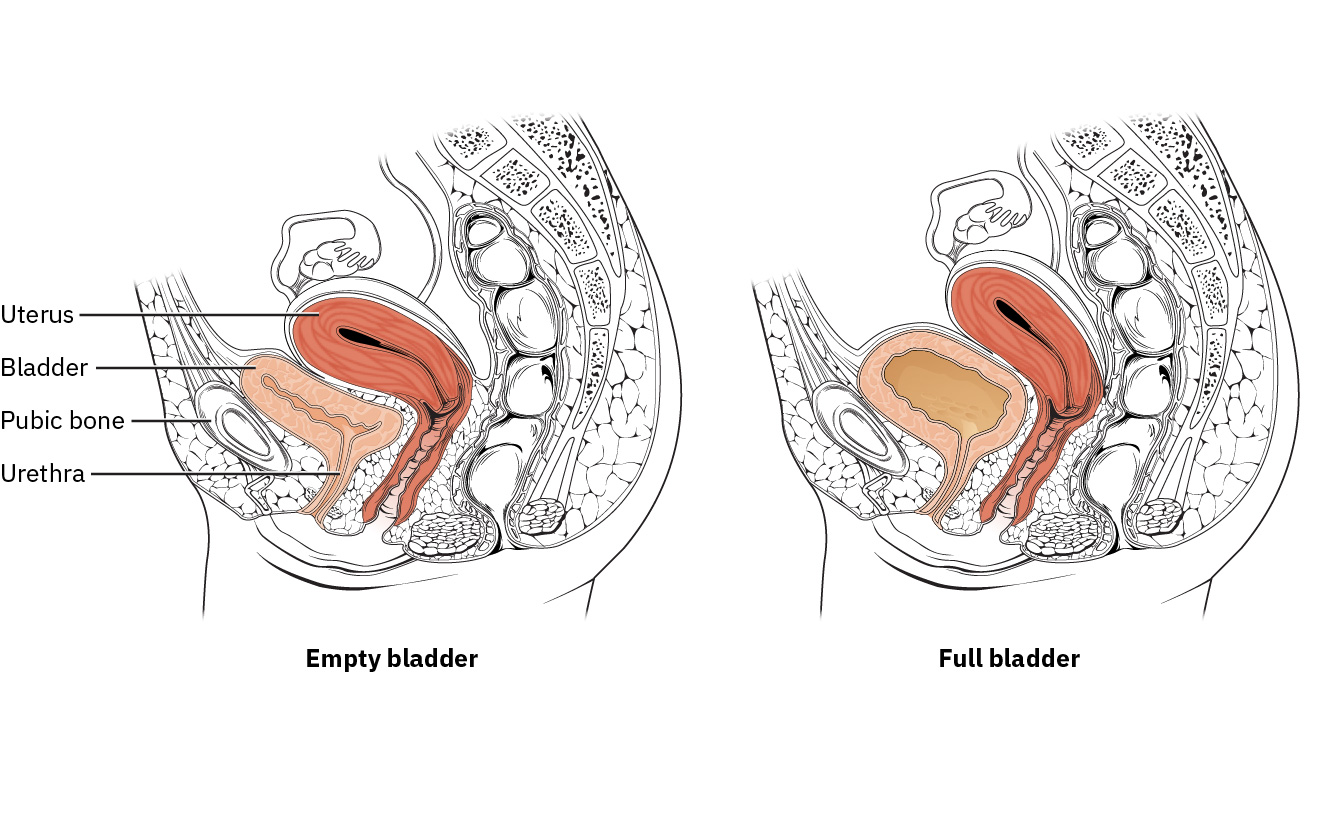

The nurse assesses for bladder distension by palpating the abdomen above the symphysis pubis. See Figure 11.17[13] for an illustration of assessing a full bladder in relation to the client’s fundus.

A distended bladder can displace the uterus to the left or right instead of remaining midline in the abdomen and cause subinvolution. See Figure 11.18[14] for an image of a displaced uterus due to a distended bladder.[15]

Urine output is measured with each void to assess for adequate output. If concerns arise regarding potential urinary retention, a bladder scanner may be used based on agency policy to assess for excessive residual urine after voiding. If excessive residual amounts of urine are present after voiding, the health care provider is notified with anticipated orders for intermittent catheterization to ensure complete bladder emptying and involution of the uterus.

Bowel

The nurse asks the client if they have passed flatus (gas) or had a bowel movement since delivery and documents the date of the last bowel movement in the electronic health record. The nurse assesses for abdominal pain and for any concerns the client may have regarding bowel movements related to perineal pain or hemorrhoids. The abdomen is auscultated for bowel sounds and then palpated. The abdomen should feel soft without firm stools present. Flatulence can cause a distended, taut abdomen and pain.

Perineum

If the client experienced vaginal delivery or labored prior to a cesarean birth, the nurse asks the client about perineal pain. The perineum is easiest to assess by requesting the postpartum client to lay on their side and then lifting one side of their buttocks to assess the perineum.

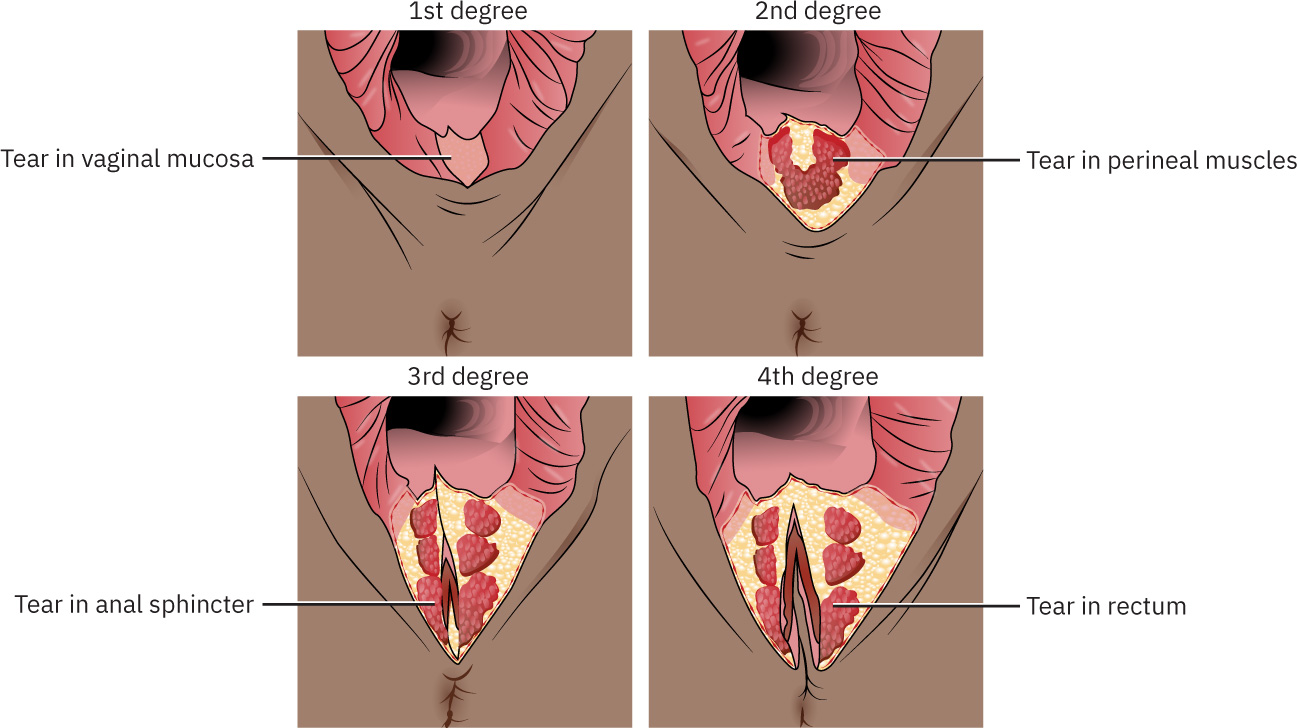

If the client had a vaginal birth, lacerations may be present. See Figure 11.19[16] for an illustration of perineal lacerations. Lacerations are categorized by degrees from first to fourth degree[17]:

- First-degree laceration: Limited to the perineal skin and vaginal mucous membrane.

- Second-degree laceration: Perineal skin, vaginal mucous membrane, underlying fascia, and central tendon of the perineum that lies between the vagina and the anus.

- Third-degree laceration: Areas of the second degree with extension through the anal sphincter that may extend up the anterior wall of the rectum.

- Fourth-degree laceration: Areas of the third degree with extension through the rectal mucosa into the lumen of the rectum.

The mnemonic REEDA (Redness, Edema, Ecchymosis, Discharge, and Approximation) is used when assessing lacerations and incisions related to episiotomy or cesarean births. It has standardized scoring that is used to monitor the healing process and detect signs of infection, poor wound healing, or other complications requiring prompt notification of the health care provider. REEDA includes the following components[18]:

- Redness: Redness surrounding the site can be a sign of inflammation or infection and is measured on a scale from none to severe.

- Edema: Swelling around the incision site may indicate tissue trauma, inflammation, or infection. The degree of edema is assessed on a scale from none to severe.

- Ecchymosis: Bruising or discoloration around the incision area may occur from tissue trauma that gradually resolves during the healing process.

- Discharge: Secretions from the incision site may include wound exudate, blood, or other types of fluid. The amount, color, and odor of the discharge are noted during the assessment.

- Approximation: Approximation refers to the alignment of the edges of the incision as they heal. Good approximation indicates that the incision edges are aligning well, while poor approximation can suggest separation or wound dehiscence.

See Table 11.5d for standardized scoring of the components of the REEDA assessment.

Table 11.5d. REEDA Assessment Scoring[19]

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| R: Redness | None | < 0.25 cm of incision bilaterally | < 0.5 cm of incision bilaterally | > 0.5 cm of incision bilaterally |

| E: Edema | None | < 1 cm from incision | 1–2 cm from incision | > 2 cm from incision |

| E: Ecchymosis | None | < 0.25 cm bilaterally or < 0.5 cm unilaterally | 0.25–1 cm bilaterally or 0.5–2 cm unilaterally | > 1 cm bilaterally or > 2 cm unilaterally |

| D: Discharge | None | Serous | Sero-

sanguineous |

Bloody or purulent |

| A: Approximation | No separation of wound edges | < 3 mm separation of wound edges | Separation of skin and subcutaneous fat | Separation of skin, subcutaneous fat, and fascia |

The REEDA score is interpreted using the following ranges[20]:

- 0-5: Well-healed

- 6-10: Moderate healing

- 11-15: Poor healing

During the perineal assessment, the nurse also assesses for perineal hematoma that appears as a swollen, firm, bluish-purple discoloration between the vagina and anus, indicating a collection of blood beneath the skin. It may feel firm to the touch and cause discomfort if palpated. It can also cause pain when sitting or walking, depending on its location and size. Hematomas should be reported to the health care provider for additional evaluation because they may require medical interventions.

Extremities

The client’s lower extremities are assessed for edema, deep tendon reflexes, clonus, and signs of deep vein thrombosis (DVT). The amount of expected edema varies across clients based on the amount of edema present during their pregnancy, the amount of IV fluids they received during labor and delivery, and if they were previously diagnosed with preeclampsia. Worsening edema should be promptly reported to the health care provider.

Clonus is assessed by dorsiflexing the client’s foot and assessing for rhythmic plantar contractions. Clonus is generally accompanied with hyperreflexia. Deep tendon reflexes are expected to be normal (2+). Clonus and/or hyperreflexia indicate increased risk of seizures and require notification of the health care provider for suspected preeclampsia.

View a supplementary YouTube video[21] on assessing for clonus and hyperreflexia:

Postpartum clients are at increased risk of developing blood clots due to changes in blood flow and other factors related to pregnancy and childbirth. The nurse assesses pedal pulses and capillary refill of the extremities, as well as for signs of a DVT, including unilateral edema, redness, and warmth. When assessing the legs, the nurse exposes both legs from the feet to the thighs to allow for visual comparison of both extremities for differences in size and color, paying particular attention to the calves. The lower limbs are palpated from the calves to the thighs for warmth, edema, and firmness while asking the client if they experience pain or discomfort. If one extremity appears more edematous than the other, both calves are measured and documented. Signs of a DVT are promptly reported to the health care provider for urgent evaluation and treatment. A DVT can dislodge and become a life-threatening pulmonary embolism, causing shortness of breath and chest pain.

To prevent DVTs, nurses encourage early ambulation. If ambulation is restricted, such as the first 12 hours after a cesarean birth, sequential compression devices, TED hose, and anticoagulants (such as enoxaparin or heparin) may be prescribed to prevent blood clots from forming.

Emotional

The postpartum period is a time of change and transition and can be stressful for the client and their support person. The nurse supports the childbearing family and encourages them to talk about their perceptions and feelings surrounding the birth.

The nurse assesses for behaviors related to the common psychological phases of taking-in, taking-hold, and letting-go as the client and partner become adjusted to the parental role:

- Taking-In: During the first one to three postpartum days, the client has a great need to talk about the labor and birth experience and may be preoccupied with her own needs. Sleep and rest are major physiological needs during this phase.

- Taking-Hold: During Days 4-10 and sometimes for several weeks, the client becomes more independent and ready to care for themselves and the newborn. The client and partner begin to display parental roles and attachment behaviors, and new parents may require lots of reassurance. The nurse knows this phase is a good time to provide health teaching about infant care. During this phase, the mother may also begin to experience feelings related to the “baby blues.”

- Letting-Go: The letting-go phase begins several weeks after delivery. The parents establish a new parental role identity with focus on the family unit.

Nurses assess attachment behaviors as the parents and newborn interact by observing them make eye contact, touch, kiss, and hold the infant. During this attachment period, parents may display behaviors such as fingertip exploration, en face positioning, and engrossment. En face positioning is where the parent’s face and infant’s face are approximately eight inches apart. Engrossment by new parents is displayed by intense interest and absorption in the newborn. The nurse may see the parent looking at the infant for prolonged periods of time. Other attachment behaviors include soothing the newborn and being attentive to their needs. Nurses positively influence parental role attainment and secure attachments by listening and answering questions, providing health teaching and anticipatory guidance, and decreasing the time the newborn is apart from the parents.[22]

Nurses are aware that attachment behaviors can be influenced by a number of factors, including cultural beliefs and practices, the parental relationship, the stability of the home environment, and family patterns of communication. Conditions that can affect bonding and secure attachment include insufficient finances, chaotic home environment, lack of family support, the need to quickly return to work, substance misuse, and preterm birth. Postpartum parents who exhibit little eye contact, avoid holding the newborn, and do not find joy in their new role may lack emotional bonding and attachment. If these behaviors are noticed, the nurse notifies the health care provider and initiates a consult with social services.[23]

Review information about parent-newborn attachment in the “Psychosocial Adaptation to Parenthood” section.

Depression

The nurse administers a postpartum depression screening tool to postpartum mothers based on agency policy, such as the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS), and provides health teaching about the baby blues and postpartum depression. The nurse advises the client and her partner to contact the health care provider if depressive mood symptoms last longer than two weeks.

Read more about symptoms of baby blues and postpartum depression in the “Postpartum Complications” section.

Psychosocial Assessment

Nurses assess the client’s anticipated support system for assistance at home. Extended family members and friends often provide emotional and physical support to new parents, such as bringing nutritious food and providing time for them to rest while caring for their newborn. If a support system is not available, the nurse makes appropriate referrals to local community resources.[24]

Nurses perform a cultural assessment to align postpartum care with the cultural values and beliefs of the client. The nurse asks open-ended questions about the client’s cultural and/or religious beliefs, food preferences and restrictions, traditional postpartum practices they would like to follow, their family support system, and if there are any cultural considerations regarding health care decision-making. The nurse is mindful of nonverbal communication and respects the client’s privacy and boundaries while performing a psychosocial assessment. By assessing and advocating for the client’s cultural preferences, a supportive environment is created for the postpartum person to transition into their new parental role.[25]

Review examples of traditional cultural beliefs in the “Cultural Considerations” subsection in the “Psychosocial Adaptation to Parenthood” section.

Analysis of Assessment Findings

The nurse analyzes assessment findings to create or modify the nursing care plan. Some findings require immediate intervention and prompt notification of the health care provider. Table 11.5e summarizes normal and common abnormal postpartum assessment findings, along with suggested nursing interventions.

Table 11.5e. Analyzing Assessment Findings[26]

| Focused

Assessment |

Normal Findings | Abnormal Findings | Nursing Interventions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vital signs |

|

|

|

| Breasts |

|

|

|

| Uterus/

Fundus |

|

|

|

| Lochia |

|

|

|

| Bladder |

|

|

|

| Bowel |

|

|

|

| Perineum |

|

|

|

| Extremities |

|

|

|

| Emotions/

Attachment |

|

|

|

Diagnosis (Analyze Cues)

Nurses establish nursing diagnoses for clients based on assessment findings. Nursing diagnoses may be problem-focused, risk, or health promotion diagnoses.

Examples of problem-focused nursing diagnoses include the following[27]:

- Impaired Comfort related to treatment regimen associated with episiotomy repair

- Disturbed Sleep Pattern related to frequent newborn feeding schedule

- Impaired Breastfeeding related to inadequate parental knowledge regarding breastfeeding techniques

Examples of risk diagnoses include the following[28]:

- Risk for Infection as evidenced by impaired skin integrity associated with cesarean section surgical incision

- Risk for Impaired Attachment as evidenced by parent-child separation in the NICU due to neonatal illness

- Risk for Bleeding as evidenced by pregnancy complication

- Risk for Urinary Retention as evidenced by weakened pelvic floor muscles

- Risk for Ineffective Coping as evidenced by inadequate social support associated with maturational crisis

Examples of health promotion diagnoses include the following[29]:

- Readiness for Enhanced Parenting as manifested by the client’s desire to enhance positive parenting practices

- Readiness for Enhanced Self-Care as evidenced by the client’s desire to enhance self-care behaviors, such as proper nutrition, rest, exercise, and stress management, for optimal postpartum recovery

- Readiness for Enhanced Breastfeeding as manifested by the client’s desire to exclusively breastfeed

- Readiness for Enhanced Knowledge as manifested by the client’s desire to enhance learning about postpartum self-care practices, including wound care, perineal hygiene, nutrition, and exercise

Outcome Identification (Generate Solutions)

Goals for postpartum care depend on the individualized nursing diagnoses and specific circumstances. Outcome criteria are established that are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, and time oriented. Sample SMART goals related to postpartum care are as follows:

- The mother and newborn will demonstrate good latch during breastfeeding with a LATCH score of 8 or higher after the teaching session.

- The amount of the client’s lochia rubra will not saturate a peripad within one hour or less.

- The client will void regularly with less than 250 mL residual volume after voiding during the hospital stay.

Implementation (Take Action)

Pharmacological Interventions

Nurses may administer several classes of medications during the postpartum period. Common medications include the following:

- Analgesics: Acetaminophen and ibuprofen are prescribed for mild to moderate pain, and opioids are prescribed for severe pain, typically after cesarean deliveries.

- Stool Softeners/Laxatives: Docusate, polyethylene glycol, or bisacodyl may be prescribed to prevent and treat constipation.

- Antibiotics: Antibiotics may be prescribed to treat wound infection associated with episiotomy repair, laceration repair, or cesarean section incision.

- Anticoagulants: Heparin or enoxaparin may be prescribed after cesarean section to prevent deep vein thrombosis.

- Hormonal Medications: Birth control pills, patches, or injections may be prescribed for contraception. Progestin-only contraceptives are typically prescribed for women who are breastfeeding.

- Iron Supplements: Iron supplements may be prescribed if the client is diagnosed with anemia due to blood loss during childbirth or iron-deficiency anemia.

- Prenatal Vitamins: Clients who are breastfeeding are typically encouraged to continue to take their prenatal vitamins.

Read more information about these classes of medications in the following sections of Open RN Nursing Pharmacology, 2e: “Nonopioid Analgesics,” “Opioid Analgesics and Antagonists,” “Antidiarrheal Medications and Laxatives,” “Antimicrobials,” “Blood Coagulation Modifiers,” and “Hormonal Contraceptives.”

Read more about iron supplementation in the “Iron-Deficiency Anemia” section in Open RN Health Alterations.

Provide Comfort

Common sources of postpartum pain include perineal pain, hemorrhoids, urinary discomfort, uterine cramping, breast discomfort with lactogenesis, bowel discomfort, and additional discomforts if a cesarean delivery was performed. Pain is managed by the nurse with nonpharmacological and pharmacological interventions.

Perineal and Hemorrhoid Discomfort

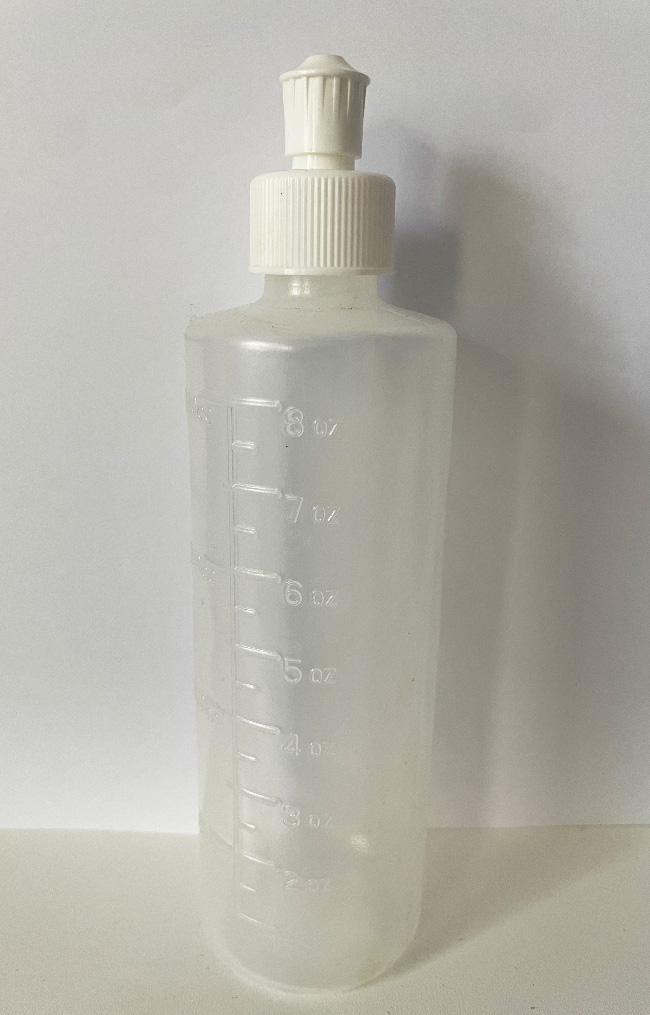

Perineal discomfort and hemorrhoids are common after vaginal delivery. In addition to administering acetaminophen or ibuprofen, nurses encourage several nonpharmacological measures such as ice packs, warm showers or sitz baths (sitting in a warm, shallow bath), peri bottles, topical analgesics such as witch hazel pads and lidocaine, and hemorrhoid cream. Ice packs or cold gel packs reduce swelling and pain and can be applied to the perineum for the first 24 hours (10-20 minutes on and 20 minutes off and repeated as needed). Warm showers and/or sitz baths are encouraged after the first 24 hours to promote vasodilation and healing. Peri bottles are plastic bottles with a spray spout that are filled with warm water and gently sprayed on the perineum for cleansing and comfort after voiding and bowel movements. See Figure 11.20[30] for an image of a peri bottle. Topical analgesics and hemorrhoid cream are applied as prescribed.

The actions and instructions for these nonpharmacological comfort measures are summarized in Table 11.5f.

Table 11.5f. Perineal and Hemorrhoid Comfort Measures[31]

| Comfort Measure | Action | Instructions |

|---|---|---|

| Ice pack | Reduces swelling and numbs the painful area | Apply an ice pack or cold pack to the perineum or hemorrhoids for 10–20 minutes at a time for the first 24 to 72 hours after birth. |

| Warm showers and sitz baths | Speeds healing by increasing blood flow to the injured area, soothes pain, reduces inflammation, or cleans perineum | Prepare a warm bath without soap. A shallow container may be used to only soak the perineum. Soak in water up to three times per day for 10–15 minutes. Gently pat the perineum or hemorrhoids when drying. Some health care providers recommend adding iodine, Epsom salt, or baking soda to the water, but do not do so unless directed by your health care provider. |

| Peri-bottle | Cleans and soothes perineum and hemorrhoids | Fill the peri-bottle with warm water and clean the perineum and rectal area after each void and bowel movement. Pat dry after use. |

| Witch hazel | Reduces swelling, helps repair broken skin, and fights bacteria | Apply witch hazel pads to perineum and hemorrhoids. Place witch hazel pads in refrigerator/freezer for additional comfort from coolness. |

| Lidocaine gel/foam/spray | Numbs the injured area. Some sprays have antimicrobials to fight infection | Spray perineum and rectal area after cleansing with peri-bottle or apply foam/gel to peripad after cleaning perineum and rectal area. Use after voiding and bowel movements. |

| Hemorrhoid cream/suppository with hydrocortisone | Relieves pain and itching and promotes healing | Apply to hemorrhoids or insert in rectum after bowel movements or with pain. |

Urinary Discomfort

Some clients experience lacerations near the urethra during childbirth, and perineal lacerations or episiotomies can cause swelling and dysuria that inhibit voiding. Nurses encourage clients to use the peri-bottle during and after voiding to reduce discomfort.

The client is instructed to void at least every three to four hours to prevent urinary retention. Fluid intake is encouraged for rehydration and to prevent urinary tract infection. The nurse should provide privacy while the client is voiding. If the client is unable to void, the nurse encourages ambulation and to attempt voiding while taking a warm shower. Warm water can help relax muscles and facilitate urination. If urinary retention does not improve, the nurse may perform a bladder scan according to agency policy or contact the health care provider for an order for intermittent catheterization.

Nurses encourage clients to increase their water intake to dilute the urine and decrease dysuria. The nurse also continues to monitor for signs of a urinary tract infection (UTI).

Review information about UTIs in the “Infection” subsection of the “Postpartum Complications” section.

Uterine Cramping

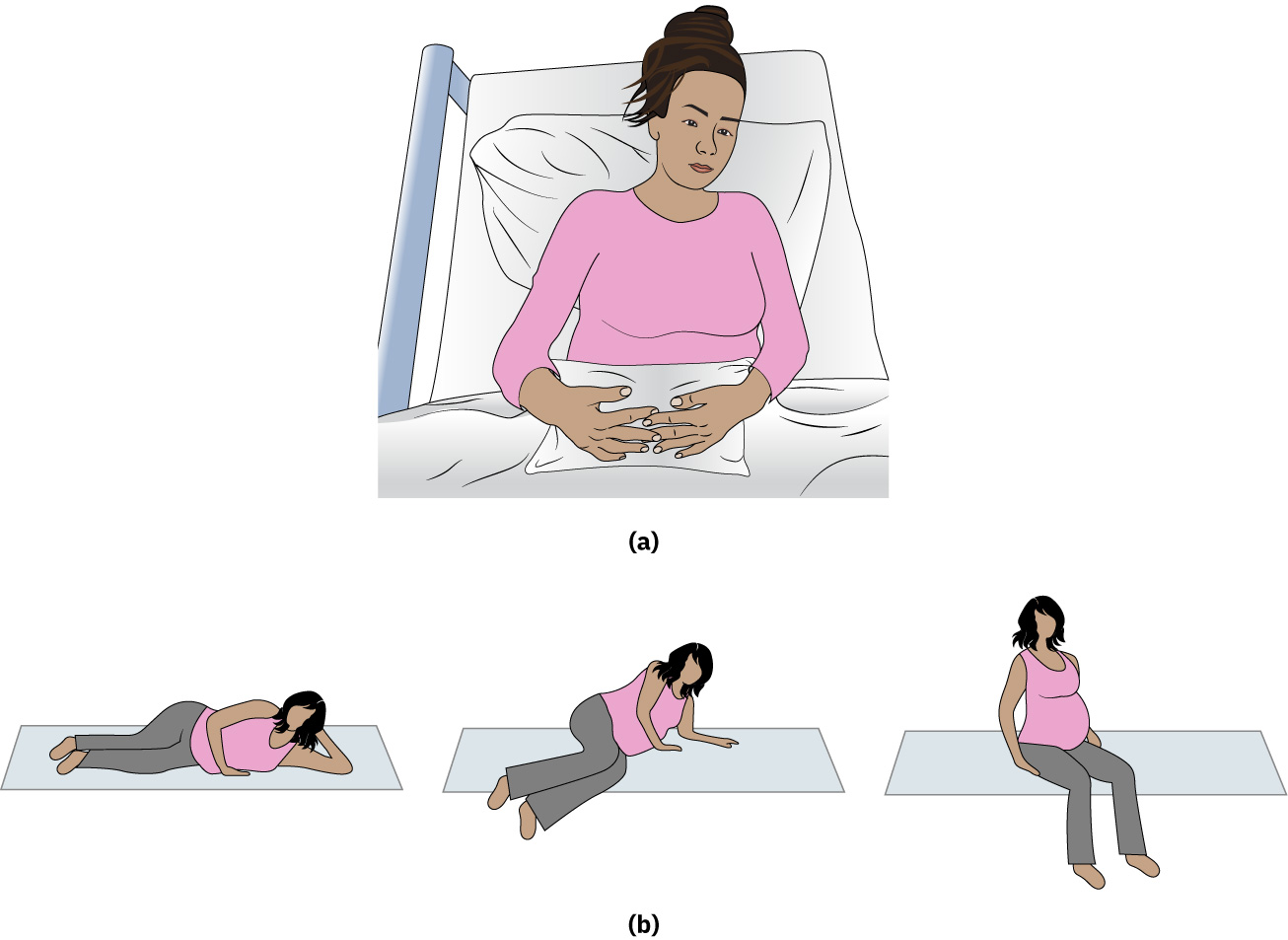

Uterine cramping is part of the uterine involution process and is strong and rhythmic. The cramping continues for two to three days and is typically more painful in multiparous persons. Uterine cramping worsens during breastfeeding because oxytocin is released with milk letdown and causes rhythmic uterine contractions. The nurse educates the client on the causes and benefits of uterine cramping and offers prescribed analgesics such as nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen to decrease the pain. It can also be helpful for the client to lie on their side with a pillow splinting their fundus or application of a warm compress or heating pad to relieve the pain.[32]

Breast Discomfort

Clients who choose to not breastfeed will have engorgement pain when their milk comes in. To decrease the discomfort, they are encouraged to wear a sports bra or support bra to compress the breasts and apply cool packs or cabbage leaves to the breasts. Research indicates that cabbage leaves contain enzymes called flavonoids that are anti-inflammatories and help reduce the swelling associated with engorgement. It is also helpful to avoid breast stimulation, such as facing warm water in the shower, as this can increase milk production.[33]

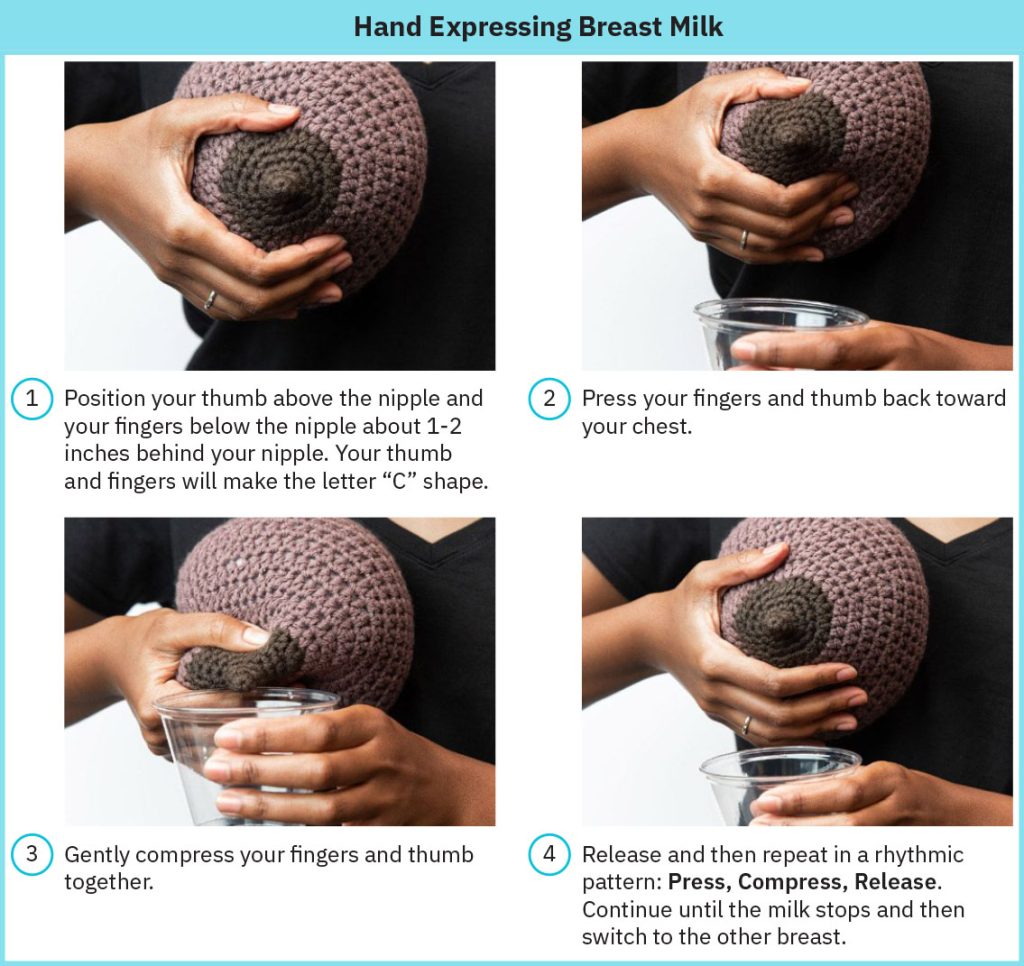

Clients choosing to breastfeed can also experience engorgement pain. Clients are encouraged to use hand expression of breast milk and frequently feed the baby. See Figure 11.21[34] for an image of hand expression of milk. The nurse also educates the client about the importance of regular, frequent feedings (every two to three hours) and checking their breasts for clogged ducts to prevent mastitis.[35]

Nurses offer cold packs or warm compresses based on the client’s preferences to help relieve discomfort from engorgement. Acetaminophen and ibuprofen may be administered for breast discomfort and are safe to take during breastfeeding.

Review information about mastitis under the “Infection” subsection of “Postpartum Complications” section.

Nipple pain may occur due to problems with latching. The nurse assists the client to achieve a good latch, but if unsuccessful, a referral can be made to a lactation consultant to help improve the latch and decrease nipple trauma. Other interventions for reducing nipple discomfort are applying breast milk to the nipple and allowing it to air dry after breastfeeding or applying nipple creams. Soap should not be used on the nipples. Lanolin is commonly used in nipple ointment. It is a thick, waxy substance found in sheep’s wool that is nourishing and protects the nipple. Other nipple creams may include olive oil, beeswax, coconut oil, or cocoa butter as a base. All nipple creams will be ingested by the newborn and should be researched for safety; some creams must be wiped off prior to breastfeeding.[36]

Bowel Discomfort

After delivery, constipation may occur due to decreased fluid intake, decreased activity, and side effects of medications such as iron supplements, opioids, or anesthesia. The postpartum client may also be hesitant to have a bowel movement related to pain from episiotomy repair, lacerations, or hemorrhoids. The client may feel bloated or have gas pain. After assessing the abdomen for hypoactive bowel sounds, distension from gas, the presence of hemorrhoids, or firm stool palpated in the left lower quadrant, the nurse encourages the client to increase their intake of fluids and fiber, as well as frequently ambulate to promote peristalsis. If the client had an episiotomy or lacerations, stool softeners and/or laxatives should be administered to prevent constipation and straining. Gas pain may be relieved with ambulation, gentle massage, chamomile or peppermint tea, and antiflatulent medications like simethicone. See additional pharmacological measures for hemorrhoids under the previous “Perineal and Hemorrhoid Discomfort” subsection.

Additional Cesarean Birth Discomforts

A client who had a cesarean birth may have additional postoperative discomforts, such as gas pain, incisional pain, and pain during repositioning and movement. Gas pain is common after a cesarean birth because anesthesia used during surgery decreases peristalsis, causing constipation and difficulty passing gas. Additionally, the opening of the peritoneum during surgery allows air to become trapped in the abdomen. This air must be absorbed and released as flatulence. To help release gas, the nurse encourages early and frequent ambulation. Simethicone is often prescribed to relieve gas pain.[37]

Clients may experience incisional pain with coughing, movement, and ambulation. When coughing, deep breathing, or getting in and out of bed, the client is encouraged to splint their incision by placing a pillow over the lower abdomen. It is also helpful to get in and out of bed using a lateral position before sitting up. See Figure 11.22[38] for an illustration of an abdominal splint and getting out of bed from a lateral position. In addition to prescribing analgesics, some health care providers will also order an abdominal binder to act as a splint.

Administer Vaccinations

There are several vaccinations that nurses may administer to clients during the postpartum period based on CDC recommendations, including influenza; COVID-19; tetanus, diphtheria, acellular pertussis (Tdap); measles, mumps, rubella (MMR); and Rh immune globulin (Rhogam). It is safe for women to receive most vaccines right after giving birth, even if breastfeeding.[39]

- Influenza: The CDC recommends administering the influenza vaccine to postpartum clients during the flu season if they have not already received their annual dose to protect them and their infant for several months after birth from flu-related complications.[40]

- COVID-19: The CDC recommends annual COVID-19 vaccination for everyone aged six months and older. If a client did not previously receive the COVID-19 vaccine during pregnancy, it can be administered during the postpartum period to protect the client and their baby from COVID-19 related complications.[41]

- Tdap: Pregnant women are encouraged to get the Tdap vaccine at any time during pregnancy to protect themselves and their baby from pertussis, also known as whooping cough. Whooping cough can be deadly for newborns. This vaccine is recommended during every pregnancy, regardless of the length of time since the previous dose. If a postpartum client did not receive a Tdap vaccine during pregnancy, they should receive it after giving birth.[42]

- MMR: If the client’s test results indicate they are not immune to rubella, the MMR vaccine is recommended during the immediate postpartum period. The client is educated to avoid sexual intercourse and use contraception to prevent pregnancy for one month after receiving the MMR vaccine.[43]

- Rhogam: Rhogam is administered to Rh-negative women who delivered Rh-positive infants to prevent Rh sensitization. Rh sensitization from exposure to fetal Rh-positive red blood cells causes a maternal antibody-antigen response, with subsequent exposures to Rh-positive blood during future pregnancy, resulting in hemolysis in the fetus (called erythroblastosis fetalis). Rhogam is administered IM or IV within 72 hours after delivery.[44]

Read current CDC recommendations for vaccines during and after pregnancy at Vaccine Recommendations Before, During, and After Pregnancy.

Provide Postpartum Health Teaching

Breastfeeding and Bottle-feeding

Nurses provide health teaching on feeding the baby. If the client chooses to breastfeed, the nurse provides breastfeeding support, including frequency of feedings, breastfeeding positions, proper latch techniques and signs of an effective latch, and how to know if the baby is getting enough milk. The nurse also addresses breastfeeding challenges or concerns, such as engorgement, nipple pain, or concerns about milk supply. Breastfeeding support is further discussed in the following subsection.

If the client is bottle-feeding, the nurse teaches about safely preparing and storing the formula, frequency of feedings, and community resources available to support mothers and infants to ensure adequate nutrition.

Breastfeeding Support

Nurses play a critical role in promoting successful breastfeeding during the initial postpartum period. Breastfeeding provides numerous benefits for both the mother and the baby, and nurses can provide guidance, education, and encouragement to ensure a positive breastfeeding experience. Common breastfeeding teaching topics include the following:

- Breastfeeding Positions: Help mothers find positions that are comfortable and effective for them and their baby.

- Latching: Show mothers how to achieve a proper latch that is essential for effective breastfeeding and preventing nipple trauma and infection.

- Frequency and Duration of Feeding: Explain the concept of feeding on demand and the importance of feeding the baby whenever they show hunger cues. Breastfed infants should be fed at a minimum of every three hours and should empty one breast before being moved to the other breast to ensure they receive hindmilk. Monitoring the number of wet diapers and stools, as well as the baby’s weight gain and growth, helps ensure that breastfeeding is adequately meeting the infant’s nutritional needs.

- Milk Supply and Demand: Educate mothers about how milk supply is established through demand and how frequent nursing stimulates milk production. Frequent feedings also decrease feelings of engorgement and prevent mastitis. Nurses encourage mothers to feed or pump frequently, especially in the first few weeks, to establish a healthy milk supply.

- Pumping and Storing Milk: Provide information about using a breast pump and properly storing breast milk.

- Breast Care and Hygiene: Explain proper breast hygiene, strategies for soothing sore nipples, and managing breast discomfort.

- Overcoming Challenges: Discuss common breastfeeding challenges, such as engorgement, nipple pain, and low milk supply, and provide strategies for managing these challenges. Offer solutions for common concerns, like milk leakage or pumping when returning to work.

- Emotional Support: Offer emotional support and encouragement, addressing any anxieties or concerns the mother may have about breastfeeding. Provide a safe space for mothers to express their feelings and ask questions. Educate partners about the importance of breastfeeding and how they can support the breastfeeding mother emotionally and practically.

- Community Resources: Connect mothers with local breastfeeding support groups, lactation consultants, or online forums where they can seek additional assistance and share experiences.

- Follow-Up Care: Schedule follow-up appointments with a lactation consultant as needed to assess breastfeeding progress and concerns and provide ongoing support.

Read more information in the “Breastfeeding” and “Bottle-feeding” subsections in the “Health Teaching” subsection under “Applying the Nursing Process and Clinical Judgment Model to Newborn Care” of the “Newborn Care” chapter.

Read additional topics about lactation in the “Human Milk Is More Than Nutrition for Infants” chapter in Nutrition Through the Life Cycle.[45]

Infant Care

Nurses provide health teaching during the postpartum period about routine infant care, such as normal voiding and stooling, bathing, umbilical cord care, circumcision care, sleep-related death prevention, car seat safety, and soothing a crying infant.

Read more information related to infant care in the “Health Teaching” subsubsection in the “Applying the Nursing Process and Clinical Judgment Model to Newborn Care” section of the “Newborn Care” chapter.

Postpartum Recovery

The nurse provides health teaching about several topics related to postpartum recovery that are discussed in the following subsections.

Nutrition and Physical Activity

Nurses provide guidance on resuming a healthy, balanced diet and staying hydrated to support postpartum recovery. Breastfeeding mothers should increase caloric intake by 340 to 400 calories per day.[49]

Clients are encouraged to prioritize rest and establish healthy sleep patterns while caring for a newborn. Naps during the day are encouraged, reinforcing the common lay advice to “rest when the baby rests.” It is helpful for the client to set aside certain times during the day to rest and other times for visits by family and friends. Although family and friend support are important, new parents should not feel the need to entertain others. Mothers are encouraged to prioritize their well-being through relaxation, stress reduction, and delegating tasks when possible.[50],[51],[52]

Strenuous activity should be avoided for the first two to three weeks postpartum. Light activity and walking are encouraged to promote muscle recovery, improve circulation, regain strength, and promote emotional well-being. Postpartum clients should avoid lifting objects heavier than their newborn for the first few weeks after birth. Clients who had a cesarean birth will have longer lifting restrictions prescribed by their provider. Exercise can be resumed based on health care provide recommendations.[53]

Perineal Care and Sexual Health

Techniques for cleaning the perineal area with a peri bottle are discussed, especially if the mother had an episiotomy or vaginal tear. The nurse explains that the client’s body is not ready to resume sexual intercourse at this time and stresses the importance of healing. It is recommended that nothing be placed in the vagina until after the postpartum visit with the health care provider. This pelvic rest allows the vagina, uterus, cervix, and placental site to heal and decreases the risk for endometritis. The nurse can explain there are ways for the couple to remain intimate without having sexual intercourse.[54],[55],[56]

The nurse inquires what contraception the client has chosen to use during the postpartum period and reinforces use of that contraception. If the client has not chosen a contraceptive method, the nurse encourages discussion with the health care provider prior to discharge. Clients should be informed it is possible to conceive soon after delivering a baby and to allow their body to heal before a subsequent pregnancy. The nurse explains that pregnancy can occur even while breastfeeding during the postpartum period.[57],[58],[59]

Read more information in the “Contraception” section of the “Reproductive Concepts” chapter.

Urinary Incontinence and Pelvic Floor Exercises

The pelvic floor muscles decrease in tone due to the stretching that occurred during labor to accommodate the fetus. This decreased tone often causes stress incontinence (urine leakage with increased abdominal pressure like coughing or sneezing). Nurses encourage clients to perform pelvic floor muscle exercises (also called Kegel exercises) to strengthen the pelvic floor and prevent incontinence. To perform Kegel exercises, the client is instructed to squeeze the muscles of the pelvic floor and contract the muscles around the urethra, vagina, and rectum in an upward motion. This muscle contraction should feel similar to the action of trying to stop the flow of urine. Clients should start by performing ten repetitions, three times per day. If a client is experiencing urinary incontinence, the nurse can suggest working up to 30 repetitions, three times a day for three months. If Kegel exercises do not resolve the urinary incontinence, pelvic floor therapy may be needed.[60]

Other Discharge Instruction Topics

In addition to the topics discussed in the preceding subsections, nurses provide discharge teaching about a variety of other topics including the following[61]:

- Medications and pain management: Information is provided on pain relief options, safe medication use while breastfeeding, and nonpharmacological pain management techniques. Guidelines for taking prescribed medications are discussed.

- Cesarean incision care: Instructions are provided on caring for the incision site, managing discomfort, recognizing signs of infection, and watching for signs of poor wound healing.

- Emotional health: Postpartum mood changes are discussed, including how to recognize signs of postpartum depression and when to contact the health care provider.

- Safety: Safety considerations are reinforced, such as car seat usage and safe sleep practices. If intimate partner violence is reported or suspected, nurses provide resources such as the location or phone numbers of local safe shelters and the Domestic Abuse Hotline at 1-800-799-SAFE.

- Recognizing postpartum complications: Warning signs of postpartum complications such as infection, excessive bleeding, and mastitis are discussed with instructions on when to contact the health care provider.

- Follow-up appointments: The importance of attending postpartum check-ups is reinforced to monitor recovery and address any concerns.

- Returning to work: The transition or returning to work is discussed, including managing work-life balance and considering breastfeeding accommodations.

- Resources and support: Information is provided for new mothers such as local support groups, online resources, and community services.

Read more information about postpartum care by the University of Michigan Health.

Adolescent Considerations

Caring for adolescent postpartum clients requires special nursing considerations due to their unique physical, emotional, and social needs. Adolescents may face additional physical challenges during the postpartum period due to their developing bodies. Nurses reinforce the importance of rest and nutrition for recovery. Adolescents may experience a range of emotions as they navigate motherhood. Offer a safe and nonjudgmental space for them to express their feelings and provide resources for counseling or support groups if needed. Adolescents may need additional guidance in building their confidence as new parents. Nurses reinforce teaching on newborn care, soothing techniques, and basic parenting skills. It may be helpful to involve the adolescent’s mother for support, if appropriate. Their support can be crucial in providing practical assistance and emotional encouragement.

Adolescent mothers are encouraged to continue their high school education and discuss options for pursuing future educational goals while also caring for their baby. Nurses offer information about educational resources available to adolescent parents, as well as community resources, such as social services, parenting classes, and local support groups. These resources can provide additional assistance and networking opportunities.

Nurses discuss healthy relationships, communication skills, and boundaries with adolescent mothers and help them understand the importance of maintaining supportive relationships during this transitional period. Nurses empower teens to make informed decisions and advocate for themselves and their child’s well-being. Body image concerns and self-esteem issues are discussed that may arise during the postpartum period. Nurses provide reassurance and information about healthy body image and self-care practices.

View this supplementary YouTube video[62] summarizing postpartum care from the Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics: Topic 13: Postpartum Care.

Postpartum Care After Pregnancy Loss

For mothers who experience pregnancy loss such as miscarriage, stillbirth, or neonatal death, it is essential to ensure emotional support during the postpartum period. Physical changes like lochia and breast milk may be painful reminders their infant is no longer with them. Nurses make referrals to bereavement counselors and local support groups and encourage follow-up evaluation with health care providers to evaluate recurrent risk and future pregnancy planning.[63]

Read “Physical Healing After a Pregnancy Loss” by University of Michigan Health.

Evaluation (Evaluate Outcomes)

During the final stage of the nursing process, nurses evaluate the effectiveness of interventions to determine if outcome criteria have been met, partially met, or not met. The nursing care plan is revised as needed to effectively meet the established outcome criteria. For example, if a breastfeeding client is experiencing difficulties with obtaining a good latch, the nurse may plan additional teaching sessions or make a referral to a lactation consultant for assistance.

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This image is derived from “steps-and-signs-icongoodlatch” by U.S. Department of Agriculture/WIC Breastfeeding Support and is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/20-1-physiologic-changes-during-the-postpartum-period#table-00002 ↵

- Jensen, D., Wallace, S., &, Kelsay, P. (1994). LATCH: A breastfeeding charting system and documentation tool. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 23(1), 27-32. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8176525/ ↵

- Nedea, D. (2020). LATCH score calculator. MD App. https://www.mdapp.co/latch-score-calculator-373/ ↵

- Jensen, D., Wallace, S., & Kelsay, P. (1994). LATCH: A breastfeeding charting system and documentation tool. Journal of Obstetric, Gynecologic, & Neonatal Nursing, 23(1), 27-32 https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/8176525/ ↵

- Nedea, D. (2020). LATCH score calculator. MD App. https://www.mdapp.co/latch-score-calculator-373/ ↵

- “78430479a02aaa3de4fbcface2476819c4012052” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “5ffebb72677302ff77c132c9687988cc1d7e2e4a” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Fundus-225x300” by unknown author is licensed under CC BY-NC-SA 4.0. Access for free at https://pressbooks.pub/nurs323/chapter/care-of-the-normal-postpartum-client/ ↵

- “bb4819d6ff8242e627f97d02a7d526c3cc689184” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “195eea31cd0fa049d3bef61e66828178fcc3b801” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Wells-Beede, E. (2022). Nursing care of women, families, and newborns. Texas A&M University. https://pressbooks.pub/nurs323/ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Armada, N. N. (2022). REEDA: Episiotomy healing acronym. https://www.osmosis.org/answers/reeds-episiotomy-healing-assessment-acronym ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2020, April 7). Clonus test positive reflex sign preeclampsia pregnancy - Nursing skills [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Reused with permission. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ufc_Ctz1hPg ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Dennis, C. L., Fung, K., Grigoriadis, S., Robinson, G. E., Romans, S., & Ross, L. (2007). Traditional postpartum practices and rituals: A qualitative systematic review. Women’s Health, 3(4), 487-502. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/10.2217/17455057.3.4.487 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2024-2026 (13th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2024-2026 (13th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2024). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2024-2026 (13th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- “267091b3aada23e888d5caa866f4c8ea7350b192” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- This image is derived from “positions 1-4” by Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.cdc.gov/infant-feeding-emergencies-toolkit/php/hand-expression.html?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/emergencies-infant-feeding/hand-expression.html ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “31035dbc70e240286a5827286b4302a808a85838” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Pregnancy and vaccines. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccine-safety/about/pregnancy.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Pregnancy and vaccines. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccine-safety/about/pregnancy.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Pregnancy and vaccines. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccine-safety/about/pregnancy.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Pregnancy and vaccines. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccine-safety/about/pregnancy.html ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Pregnancy and vaccines. https://www.cdc.gov/vaccine-safety/about/pregnancy.html ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Zempleni, S., Hanzel, E., & Christensen, S. (2022). Human milk is more than nutrition for infants. In Nutrition Through the Life Cycle. University of Nebraska-Lincoln. https://pressbooks.nebraska.edu/nutr251/ ↵

- Global Health Media Project. (2015, May 19). Breastfeeding positions - Breastfeeding series [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=NS8UyAQexBg ↵

- Global Health Media Project. (2015, August 1). Attaching your baby at the breast - Breastfeeding series [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wjt-Ashodw8 ↵

- Baby Friendly Initiative UK. (2015, June 22). UNICEF UK Baby Friendly Initiative | Hand expression [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=K0zVCwdJZw0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Maternal diet and breastfeeding. https://www.cdc.gov/breastfeeding-special-circumstances/hcp/diet-micronutrients/maternal-diet.html#:~:text=Do%20breastfeeding%20mothers%20need%20more,(HHS)%20for%20more%20information ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- University of Michigan Health. (n.d.). Postpartum care. https://www.umwomenshealth.org/resources/womens-health-education-library/postpartum-care ↵

- Lopez-Gonzalez, D. M., & Kopparapu, A. K. (2022). Postpartum care of the new mother. StatPearls. [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565875/ ↵

- Lopez-Gonzalez, D. M., & Kopparapu, A. K. (2022). Postpartum care of the new mother. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565875/ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- University of Michigan Health. (n.d.). Postpartum care. https://www.umwomenshealth.org/resources/womens-health-education-library/postpartum-care ↵

- Lopez-Gonzalez, D. M., & Kopparapu, A. K. (2022). Postpartum care of the new mother. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565875/ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- University of Michigan Health. (n.d.). Postpartum care. https://www.umwomenshealth.org/resources/womens-health-education-library/postpartum-care ↵

- Lopez-Gonzalez, D. M., & Kopparapu, A. K. (2022). Postpartum care of the new mother. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK565875/ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- University of Michigan Health. (n.d.). Postpartum care. https://www.umwomenshealth.org/resources/womens-health-education-library/postpartum-care ↵

- Association of Professors of Gynecology and Obstetrics (APGO). (2015, September 10). Topic 13: Postpartum care [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CCa50OS6jyo ↵

- University of Michigan Health. (n.d.). Postpartum care. https://www.umwomenshealth.org/resources/womens-health-education-library/postpartum-care ↵

How a baby attaches their mouth to a mother's breast during breastfeeding, the way they "clamp on" to the nipple and areola to extract milk.

The infant’s chest being against the mother’s chest, the infant’s head being straight and not turned to the side, the infant’s mouth being wide prior to latching, and the areola, not just the nipple, in the infant’s mouth.

Latch which results in painful, cracked nipples; nipples shaped irregularly after nursing; pain during breastfeeding; and a feeling of lack of emptying of the breast.

Equal to or less than 2.5 centimeter stain of lochia rubra.

Less than a 10 centimeter stain of lochia.

Equal or greater than a 10 centimeter stain of lochia.

Saturates a peripad pad in one hour or includes clots larger than a golf ball of lochia.

Limited to the perineal skin and vaginal mucous membrane.

Perineal skin, vaginal mucous membrane, underlying fascia, and central tendon of the perineum that lies between the vagina and the anus.

Areas of the second degree with extension through the anal sphincter that may extend up the anterior wall of the rectum.

Areas of the third degree with extension through the rectal mucosa into the lumen of the rectum.

Indicates that the incision edges are aligning well.

Suggest separation or wound dehiscence.

Swollen, firm, bluish-purple discoloration between the vagina and anus, indicating a collection of blood beneath the skin.

Assessed by dorsiflexing the client’s foot and assessing for rhythmic plantar contractions.

During the first one to three postpartum days, the client has a great need to talk about the labor and birth experience and may be preoccupied with her own needs. Sleep and rest are major physiological needs during this phase.

Phase that occurs four to ten days after delivery, the postpartum client’s focus turns to the newborn. The client becomes more confident in caring for the newborn and more comfortable in the maternal role, but may continue to seek support from family members and friends who can provide guidance and understanding.

Begins several weeks after delivery as the client establishes a new parental role identity and focuses on the family unit. During this phase, the client accepts physical separation from the infant, lets go of their former role as a childless person, accepts the responsibilities of parenthood, and adjusts to the infant's dependency and helplessness.

Where the parent’s face and infant’s face are approximately eight inches apart.

Intense interest and absorption in the newborn.

Sitting in a warm, shallow bath.

Plastic bottles with a spray spout that are filled with warm water and gently sprayed on the perineum for cleansing and comfort after voiding and bowel movements.

The natural process of the uterus returning to its pre-pregnancy state after giving birth.

Urine leakage with increased abdominal pressure like coughing or sneezing.