10.6 Pain Management During Labor and Delivery

Labor pain can be severe, and nurses serve a vital role in pain management using nonpharmacological interventions and administering pain medications according to the client’s preferences. During the antepartum period, prenatal classes include topics about pain management options. Many clients create a birth plan to provide nurses and health care providers with a description of their preferences for pain control during labor and delivery. As part of the admission assessment, the nurse discusses the client’s preferences for pain management and describes the available options for pain management in that agency.[1]

Several topics related to pain management will be discussed in this section, including the pathophysiology of labor pain, assessing pain, nonpharmacological pain management, systemic pain medications, and anesthesia agents used during labor and delivery.[2]

Pathophysiology of Pain During Labor and Delivery

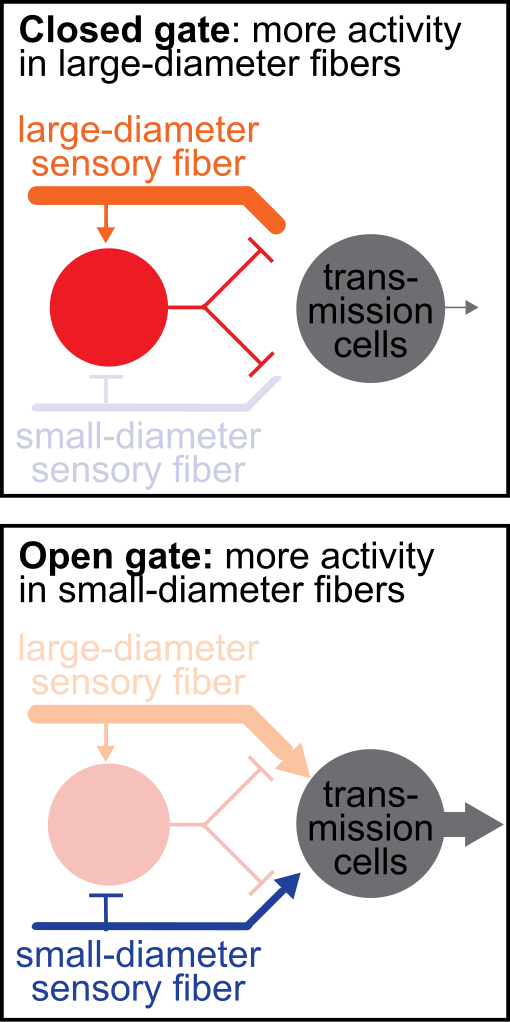

Pain is the result of complex interactions between biological, psychological, and social factors with no two individuals’ experiences being the same. The Gate Control Theory of Pain suggests that pain perception is a dynamic process influenced by physical, psychological, and sociological factors and that a mechanism in the dorsal horn of the spinal column serves as a “gate” that either allows or prevents pain signals from reaching the brain. Several interventions can help close the gate, including medications, as well as nonpharmacological interventions. Nonpharmacological interventions work by affecting the transmission of signals in the small and large nerve fibers. Small nerve fibers carry pain signals, and if the “gate” is open, these signals reach the brain where they are processed, and the individual perceives pain. However, large nerve fibers carry sensory signals, and increased activity in these fibers can help inhibit the pain signals from the small nerve fibers from reaching the brain. For example, interventions like therapeutic touch, repositioning, and free movement during labor can increase the number of signals transmitted by the large nerve fibers and, thus, inhibit the transmission of pain signals in the small nerve fibers through the “gate.”[3] See Figure 10.41[4] for an illustration of the Gate Control Theory of Pain.

There are a multitude of physical factors that affect the pain response during labor and delivery. Pain signals originate from a variety of anatomical sites during labor, including the uterine muscles as they contract, the cervix as it dilates, and the pelvic floor muscles as they stretch to accommodate the fetus during its descent through the pelvis. Additional physical factors that affect pain include the intensity of contractions, fetal positioning, maternal pelvic size and shape, maternal positioning, and discomfort from medical interventions.[5]

Several psychological factors impact pain perception during labor and delivery. Anxiety, fear, or fatigue can amplify the intensity of the pain signals sent to the brain. Anxiety and fear stimulate the sympathetic nervous system to release cortisol, a stress hormone. The resulting “fight-or-flight” response can increase pain perception. Fatigue can increase feelings of stress, amplify pain perceptions, and delay labor progress. For example, a client may be able to tolerate pain in the early stages of labor, but as the labor becomes prolonged and they become fatigued and stressed, their ability to tolerate pain may decrease. Nurses address psychological factors by creating a relaxing, welcoming environment that encourages a feeling of safety during labor and decreases client anxiety. For example, soft lighting, minimal environmental noise, and aromatherapy can help create a relaxing environment. Furthermore, interventions like distraction, guided imagery, and other relaxation techniques can decrease the intensity of pain signals and close the gate on the transmission of these signals to the brain.[6]

Labor pain is also influenced by social support. Preparing for the childbirth process by taking prenatal classes and having a partner or support person present during labor can help clients manage their pain. Nurses also provide emotional support during labor by providing health teaching and therapeutic communication with anticipatory guidance. Some clients also enlist the support of doulas.[7],[8]

Pain Assessment

Women may experience varying degrees of pain during the different stages of labor, ranging from menstrual-like cramps to severe, distressing levels of pain. Although pain is an expected part of normal childbirth, the nurse plays a crucial role in the assessment and management of pain based on the client’s preferences.

As the first stage of labor progresses, muscular uterine contractions increase, dilating the cervix and transporting the fetus from the uterus through the pelvis. Increasing intensity of contractions commonly causes an increasing intensity of pain. Nurses use pain rating scales to assess pain and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions, such as the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) or the Visual Analogue Scale (VAS). The NRS is a 10-point scale containing numbers from 0 to 10, with 0 indicating “no pain” and 10 indicating “worst imaginable pain.” The VAS is a 5-point scale that contains verbal descriptors such as “none,” “mild,” “moderate,” “severe,” and “very severe.” Nurses also assess a client’s objective and behavioral cues such as closed eyes, clenched fists, and muscle rigidity while considering that communication of pain is impacted by a client’s personal and cultural pain beliefs.[9]

Due to the emotional impact of childbirth, a client’s rating of pain is also influenced by their mood, sense of control, and sense of safety.[10] If nurses can help a client sustain the belief that the pain is purposeful (i.e., her body working to birth the baby), the pain is productive (i.e., it is taking her through a process to a desired goal), and the birthing environment is safe and supportive, the woman may be able to interpret the pain as a nonthreatening, transformative life event.[11] However, if the client is feeling unsafe or experiencing fear or anxiety, the pain may be perceived as threatening.

In addition to performing pain assessments, the nurse also assesses the client’s awareness of alternative pain relief methods. Although analgesics and anesthetics like epidurals can effectively control pain, they can also increase the risks for adverse effects such as increased duration of labor, operative vaginal birth (forceps- or vacuum-assisted birth), or cesarean section birth. Providing education about nonpharmacological pain management techniques can help a laboring client relax and feel in control, which can help them to work effectively with the physiological responses of childbirth.[12]

Nonpharmacologic Interventions During Labor and Delivery

Research indicates that many nonpharmacological interventions can help promote relaxation and reduce pain perception, although the level of evidence supporting effectiveness is low.[13] The nurse’s role is to assist and support the laboring client in implementing nonpharmacological techniques based on the client’s preferences and what they perceive works in managing their pain. The nurse also demonstrates techniques that the partner or support person can use to help provide comfort to the laboring client.[14]

Environment

The nurse begins by creating a physical environment to promote a feeling of safety, comfort, and control that promotes labor progression and decreases perception of pain. Bright lights, excessive noise, fear of the unknown, or feeling out of control can inhibit labor progression and increase the perception of pain. Conversely, a quiet, relaxing environment can allow the laboring client to focus on their body and the physiological processes of childbirth. Many laboring clients find low lighting, aromatherapy, and music based on their preferences to be relaxing.

Aromatherapy uses essential oils to aid in relaxation. Essential oils can be inhaled via a diffuser, added to bath water, or applied during massage or acupressure. The most commonly used essential oil during labor is lavender. Research indicates that aromatherapy can significantly reduce labor pain, especially during the transitional phase of the first stage of labor.[15] Geranium, orange, frankincense, and chamomile have also been found to be effective in reducing anxiety and pain during labor, and peppermint can help relieve nausea.[16]

Nurses can encourage clients to use focal points in their environment during contractions. When using focal points, the client centers their attention on a picture or an object in the room and concentrates on breathing through the contraction. The focal point is thought to help them focus on the physiological processes of their body instead of a variety of stimuli present in the room.[17]

Nurses can help clients to use guided imagery during contractions. Guided imagery uses the mind-body connection to focus the client’s awareness on a positive safe place using all of their senses. For example, a client may choose to picture a beautiful beach setting in their mind and recall the smell of the ocean, the feeling of the sand and sun, and the sounds of the ocean waves. Guided imagery refocuses the mind away from the perception of pain and stress to a state of relaxation with an associated sense of control over the situation. If the client has not previously used guided imagery, the nurse can explain how to use the technique, ask the client for their idea of a relaxing, safe place, and talk them through using their five senses to think about that place during a contraction.[18]

Breathing Techniques

Controlled breathing has been used for generations for relaxation and pain control. Many types of controlled breathing are taught in childbirth education classes. Nurses can teach a client and their partner or support person about different breathing techniques. The nurse can also demonstrate these breathing techniques during a contraction to help lead a laboring client to breathe through it[19]:

- A cleansing breath is a slow, deep inhalation through the nose and exhalation through the mouth. It can be used in preparation for an upcoming contraction or after a contraction to release tension.

- Deep abdominal breathing, also called belly breathing, is the process of expanding the abdomen on inhalation and then exhaling and relaxing the abdomen. The client can put their hand on their belly to guide their breath using their abdomen. Visualizing the breath going in and out of the abdomen is also helpful during a contraction. This type of breathing is often used in early labor.

- High chest breathing is the process of expanding the chest while inhaling and then letting the chest fall when exhaling. The client can place their hands on their chest and focus on only expanding the chest and allowing the abdomen to remain still. This type of breathing is often used in active labor.

- Chanting during labor is similar to chanting during yoga or prayer where vowel sounds are used to keep the throat open and relaxed. Supporters of chanting believe if the throat stays relaxed, the cervix will stay relaxed and open more easily. Clients may choose to listen to music that includes chanting or chant without music.

- Panting is a pattern of breathing using two short breaths and one long breath that sounds like “hee-hee-hoo.” Panting is done in a rhythmic pattern from the beginning to the end of the contraction and followed by a deep cleansing breath. It is typically used as labor is progressing and contractions become more intense.

- Open and closed glottis breathing are methods of controlled breathing while pushing. During closed glottis breathing, the client inhales deeply and then holds their breath while bearing down and pushing and counting to ten. During open glottis breathing, the client inhales deeply and then slowly exhales as they bear down to push. Research has found that both open glottis and closed glottis breathing are effective during pushing, and the laboring person should be allowed to choose which type of breathing is most comfortable for them.[20]

When clients are using controlled breathing techniques, the nurse monitors for signs of hyperventilation such as dizziness and numbness or tingling of the lips and fingertips. If a client has symptoms of hyperventilation, the nurse encourages them to use deep abdominal breathing or to exhale slowly out of pursed lips, similar to blowing out a candle.[21]

Comfort Measures

The nurse helps initiate a variety of other comfort measures such as heat or cold application, distraction techniques, and encouragement of fluids to quench thirst.

Labor is very physical work, and the client can become hot, sweaty, or nauseated. The nurse, partner, or support person can promote comfort by applying a cool cloth to the client’s forehead.

Alternating application of heat and cold can also provide comfort. Heat causes vasodilation and can improve perfusion and relieve muscular tension, whereas cold application can be comforting if the client is feeling hot. Adjusting the room environment to the client’s preferences or providing a room fan can also provide comfort.[22]

Distraction techniques, such watching television or listening to stories shared by their partner or support person, can help distract the client from discomfort.[23]

Providing fluids to the laboring client can provide comfort because they are frequently breathing in and out of their mouth, causing thirst and a feeling of a dry mouth. In many labor and delivery units, intravenous (IV) fluids are administered during labor to prevent dehydration, but this does not quench the discomfort of thirst or dry mouth. Based on agency policy and provider orders, nurses may offer frequent small sips of water or juice, ice chips, or ice pops to quench the client’s thirst and provide calories. However, the nurse also teaches the client that the digestive system slows during labor and increases the potential for nausea and vomiting, so only small amounts of fluids should be ingested at a time to help prevent vomiting. The nurse also palpates for bladder distention and encourages voiding every two hours as a full bladder can cause pain and a slow descent of the fetus.[24]

Position Changes and Movement

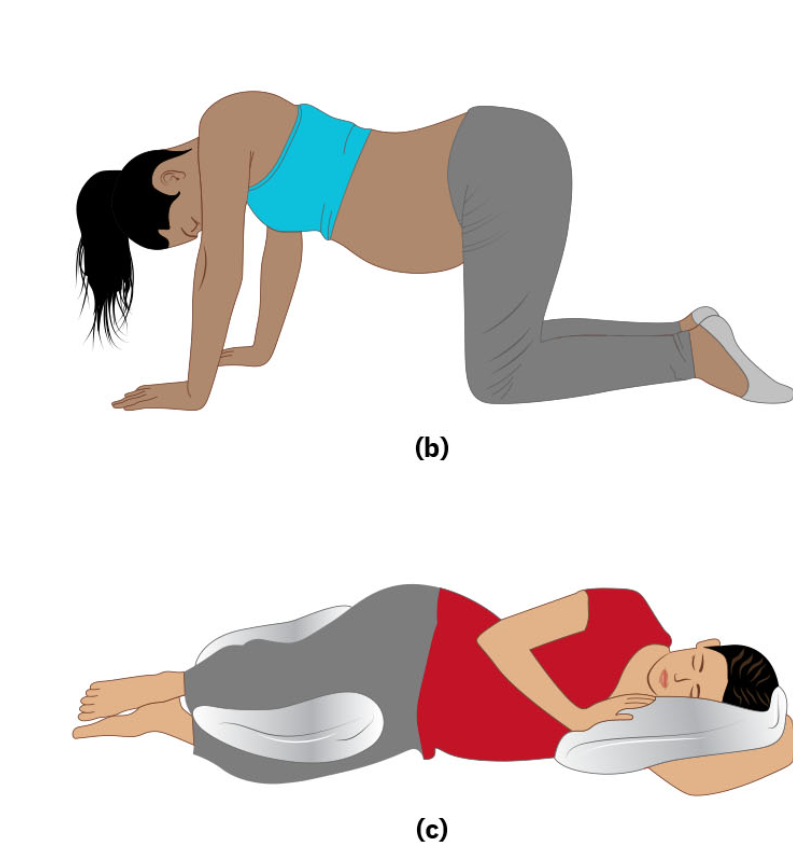

Maternal movement during labor assists with pain control and also helps move the fetus into an optimal position for birth. Changing positions during labor leads to an easier birth, provides a greater sense of control, and decreases the risk for operative vaginal birth or cesarean section birth. Nurses encourage frequent position changes during first and second stage labor. However, the client should avoid lying in a supine position to prevent vena cava compression syndrome and decreased fetal heart rate and instead use alternating side-lying positions. See Figure 10.42[25] for an illustration of changing positions during labor.

When the client begins pushing, the nurse can help reposition them laterally onto their side, assist with assuming a hands-and-knees position, or to squat. These positions are also associated with fewer perineal lacerations.[26]

Hands and Knees

Being on the hands and knees is helpful for clients, especially those with back pain related to labor. The laboring client can also perform pelvic tilts or cat-cow yoga positions. Pelvic tilts are the rocking of the pelvis by arching the back up and then sinking the back down. The hands and knees position also allows the nurse, partner, or support person to massage the client’s back, apply counter pressure, or hold a hot or cold pack on their back. Pelvic tilts can also help move a fetus who is in an occiput posterior position to assume an occiput anterior position because the heaviest part of the fetus (buttocks and back) is drawn to the anterior side by gravity.[27]

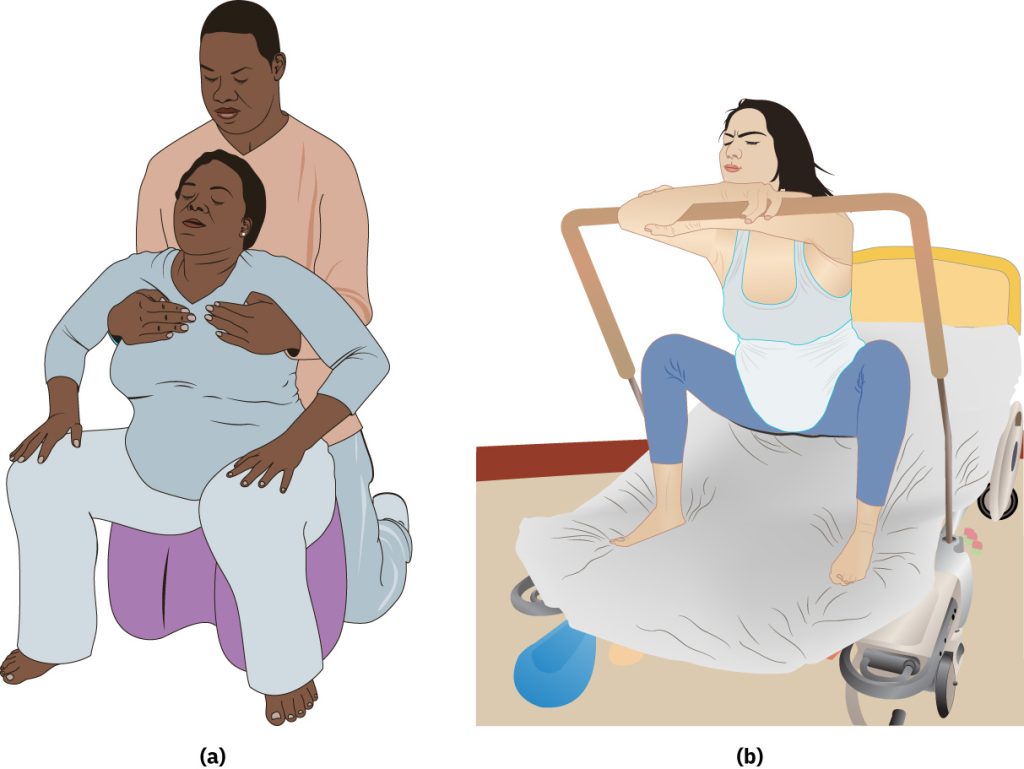

Squatting

Squatting is a good position for opening the pelvis in labor. Squatting opens the pelvic outlet and provides more room for the fetal presenting part to descend into the pelvis. Squatting can be done while the client is supported by the partner, support person, or nurse. A squat stool or a squat bar attached to the bed can also be used to help to support the client in the squatting position.[28] See Figure 10.43[29] for an illustration of the squatting position.

Walking

Walking during labor promotes freedom of movement and relaxes the muscles. Walking moves the maternal pelvis, which also moves the fetus and encourages the fetal presenting part to descend into the pelvis. If the client has no risk factors, intermittent auscultation can be used for fetal monitoring. If external continuous monitoring is required, some labor and delivery units have wireless external fetal heart rate monitors that can be used while the client is walking if there are no contraindications.[30]

Rocking

Rocking is rhythmic and soothing. It relieves tension in the hips and aids in repositioning the fetus. It can also be used as a distraction during a contraction. Many things can help a laboring client rock, such as a rocking chair, birthing ball, or toilet. The client can sit on a birthing ball and rock back and forth or side to side. If there are no contraindications, the client can sit forward or backward on a toilet and rock. A side-lying position can also help the client rock their hips.[31]

View a supplementary YouTube video[32] on pelvic tilts at Pelvic Tilt – Pregnancy Exercise – Oh Baby! Fitness.

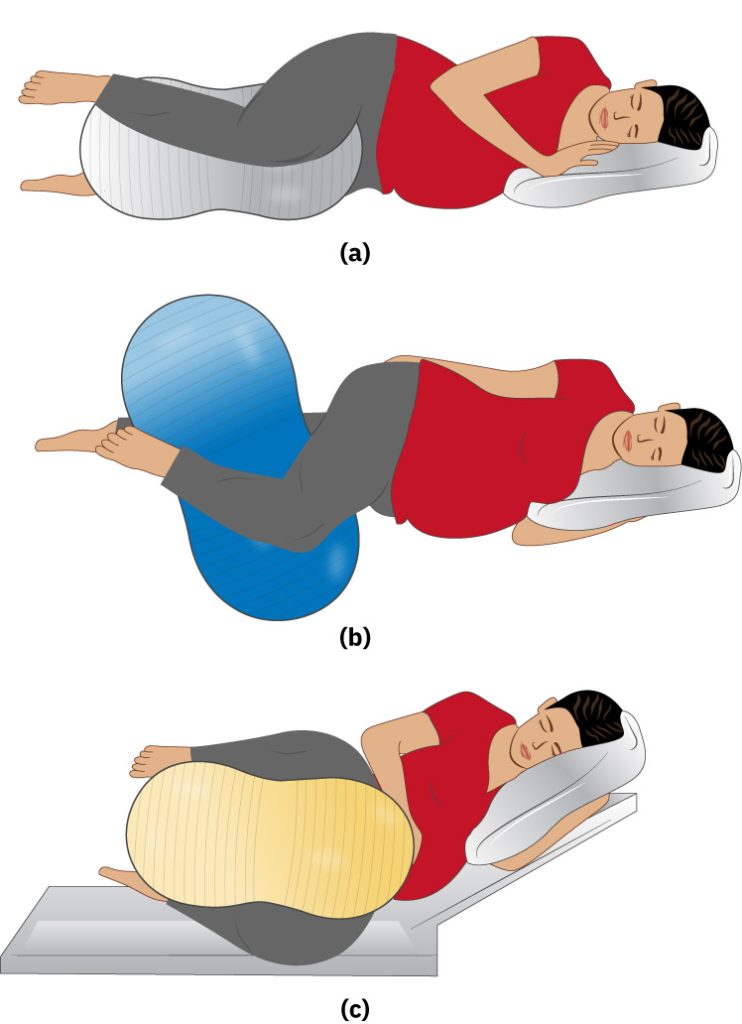

Positioning With Birthing and Peanut Balls

Birthing balls and peanut balls are used to assist laboring clients to open their hips and mimic a squatting position. Research indicates that birthing balls have been shown to significantly decrease pain during labor.[33] They can also aid in the descent of the fetus through the pelvis and decrease the length of labor in clients without an epidural. Figure 10.44[34] illustrates various ways to position the laboring client using a peanut ball.

Positioning With an Epidural in Place

If an epidural is placed during the first stage of labor, it is crucial for the nurse to encourage position changes at least every 20 to 30 minutes because the laboring client will not experience the physiologic signals to make these position changes due to the effects of the epidural medication. Positions that can be helpful with an epidural in place include side-lying, upright with symmetric and asymmetric leg positioning, pelvic tilts, and hands and knees (if able) to encourage engagement of the fetal head into the maternal pelvis. A peanut ball can also be encouraged for a client with an epidural in place to stimulate fetal rotation and descent.[35]

Hydrotherapy

Using water to provide pain relief during labor is called hydrotherapy. Taking a warm bath or shower can help relax muscles and provide relief during contractions. Some birthing centers also have whirlpools that allow the client to float, decreasing the weight of the uterus and fetus on the pelvis. Hydrotherapy has been shown to decrease pain, encourage movement, lower anxiety, shorten labor, and improve satisfaction with the birthing experience. Research has shown no negative side effects of hydrotherapy in the first stage of labor. Note that hydrotherapy is different from waterbirth, the immersion of the client in water during the second stage of labor and delivery of the fetus. Immersion and waterbirth are contraindicated with maternal fever, vaginal bleeding, preterm gestation, or the presence of infectious disease.[36]

During hydrotherapy, the nurse’s role is to prepare the warm water, assist the client into the shower or tub, and position the client in a shower so the water stream is focused on the area that feels best. The nurse can also encourage the partner or support person to help by also being in the shower or tub or by pouring warm water over the client’s back or abdomen. The nurse also ensures safety of the client and the fetus by performing intermittent auscultation of the fetal heart rate or using waterproof, wireless continuous fetal monitoring during hydrotherapy.[37]

Massage and Therapeutic Touch

Massage is defined as a physical manipulation of tissue that can be provided in different ways, depending upon the preference of the laboring client. Massage during labor has been shown to decrease anxiety, provide comfort, and release endorphins. However, nurses consider that massage may be uncomfortable for clients who have experienced sexual assault or for those whose personal or cultural beliefs do not approve of massage. Massage can include soft or firm touch, moving touch, or still touch and can be performed skin-to-skin or with a massage tool. Some birthing centers have massage therapists available for laboring clients, or the nurse, partner, or support person may assist with performing massage. For example, the back and sacrum are common areas of discomfort during labor. The nurse, partner, or support person can use a tennis ball to massage the client’s lower back and sacrum to relieve pain. Using essential oils such as jasmine, clary sage, rose, and lavender can also improve the effectiveness of the massage.[38]

View the following supplementary YouTube video[39] on labor massage: 5 BEST Labor Massage for Pain Management!

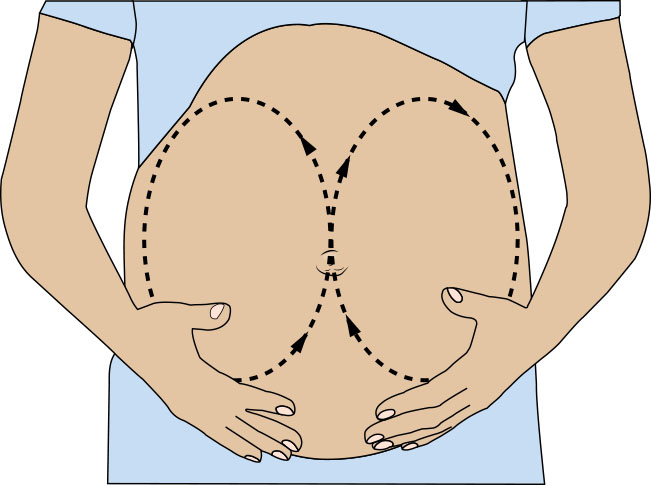

Effleurage is light stroking massage using the tips of the fingers in slow, long strokes on the client’s abdomen in rhythm with contractions. Effleurage causes relaxation, closes the pain gate, and releases endorphins. Self-effleurage is a good self-comforting technique for clients who prefer not to be touched by other people during labor.[40] See Figure 10.45[41] for an illustration of effleurage.

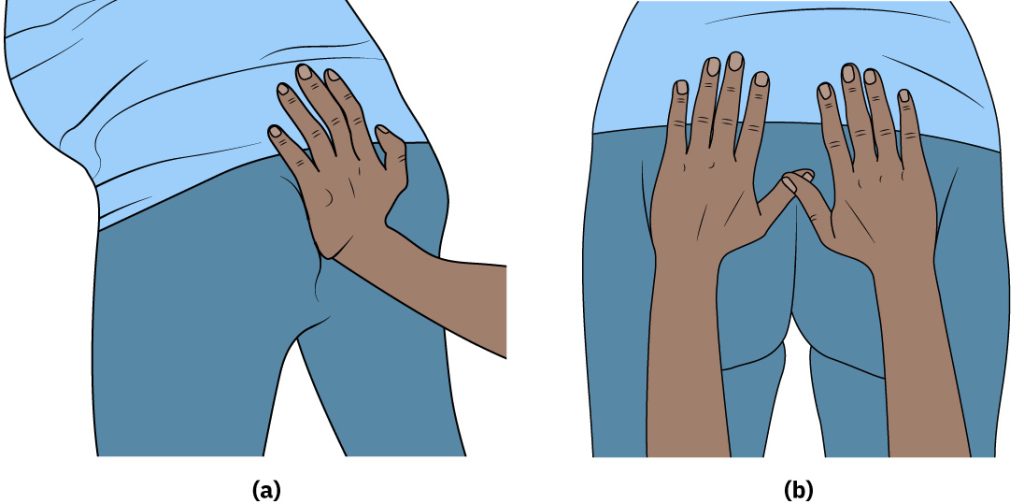

Counter pressure is the act of providing sustained firm pressure to the client’s back, hips, sacrum, or other joints. Counter pressure is helpful for clients experiencing back pain during labor. See Figure 10.46[42] for an illustration of counter pressure.

A common type of counter pressure in labor is a “hip squeeze.” The nurse, partner, or support person places their palms on the client’s hips and applies firm pressure while pushing the hips toward each other. This pressure relieves pain and also opens the pelvis to allow descent of the fetus.

Sterile Water Injections

Sterile water injections are procedures typically used by midwives to relieve back pain during labor based on the Gate Control Theory of Pain. During this procedure, a small amount of sterile water is injected under the client’s skin at specific points on their lower back. The injection creates a papule that blocks pain signals from reaching the brain. Research indicates this procedure is safe and relatively effective 30-90 minutes after injection.[43]

TENS

Transcutaneous electrical nerve stimulation (TENS) is the application of electrical currents to the surface of the skin, which blocks pain signal transmission and releases endorphins. Research indicates that TENS is effective in reducing labor pain and may shorten the duration of the active phase of the first stage of labor.[44]

View a supplementary YouTube video[45] on TENS: Using TENS for Labour Pain | Physiotherapy | Mater Mothers.

Biofeedback

A mind-body practice called biofeedback may be taught during prenatal classes. The client then practices with biofeedback prior to going into labor. Biofeedback promotes a client’s sense of control over the labor process by promoting the feeling that their mind has control over their body. Biofeedback includes a sensor that monitors pain reactions in the body while the client uses techniques to control those reactions. For example, during a contraction, the client can view an increase in their pulse on a pulse oximeter and then use controlled breathing techniques to control their pulse during a contraction.[46]

Hypnosis

Hypnosis works by inhibiting neuronal communication between the sensory cortex, amygdala, and limbic system and decreasing the conduction of pain sensations. Pregnant clients take prenatal classes to learn how to use self-hypnosis, along with controlled breathing, relaxation techniques, and visualization during contractions to control pain. Clients are provided self-hypnosis recorded sessions to listen to and practice during pregnancy. These recordings provide affirmations, visualizations, and instructions on getting into a hypnotic state. Laboring clients listen to these sessions while in labor, turn inward, and should not be disturbed during the contraction. The nurse is aware that the environment should be quiet with dim lighting to promote the hypnotic state in clients using self-hypnosis.[47]

Acupressure

Acupuncture, used in traditional Chinese medicine, involves the insertion of fine needles into different areas of the body to address imbalances of energy (in the form of qi). Acupressure is based on the same principle as acupuncture but involves the therapist using their hands and fingers to stimulate specific body points, rather than needles. Research indicates acupressure can effectively reduce labor pain.[48]

Acupressure increases the release of neurotransmitters such as serotonin and dopamine, causing an analgesic effect. Certain pressure points throughout the body are thought to aid in pain relief, while other areas are thought to increase labor contractions to expedite birth. The most common areas for acupressure during labor are in the hands, feet, and ears. Acupressure is typically performed by a traditional Chinese medicine specialist, chiropractor, or massage therapist. Nurses can obtain special training to become proficient in acupressure.[49]

Pharmacological Interventions During Labor and Delivery

Several types of pharmacological agents may be administered to clients during labor and delivery to reduce pain and discomfort. Analgesics are medications used to inhibit the transmission of pain impulses to the brain without loss of consciousness. Systemic analgesics are typically administered for rapid pain relief during labor by inhalation (such as nitrous oxide) or through the parenteral route (such as opioids or acetaminophen). The efficacy of these medications in treating pain during labor varies, as do the maternal and perinatal side effects.[50]

Anesthesia temporarily induces a loss of feeling or awareness. There are three types of anesthesia: local, regional, and general. Local anesthesia induces a loss of feeling in a small area of the body; regional anesthesia induces a loss of feeling in a specific part of the body; and general anesthesia induces a loss of feeling and complete loss of awareness, which feels like a very deep sleep. Epidurals are an example of a regional anesthetic used during labor and delivery.[51] Anesthetics are further discussed in the “Anesthetics” subsection.

The laboring client and their partner may be concerned about how medications administered during labor and delivery will affect the infant. The nurse provides health teaching about medications and their side effects, as well as the potential effects of unmanaged labor pain for the client and fetus. Pain can cause not only maternal suffering but also hyperventilation and alkalosis, resulting in decreased fetal blood flow and oxygenation. Poorly managed pain can also stimulate the neuroendocrine stress response, causing elevated catecholamine levels that increase maternal peripheral vascular resistance and decrease uteroplacental perfusion. Decreased uteroplacental perfusion results in decreased fetal oxygenation, slowed fetal heart rate, and fetal acidosis. Furthermore, women who experience unrelieved pаiո during сhildbirth may be more likely to develop postpartum depression.[52]

Analgesics

The most commonly used systemic analgesics used during labor are opioids, mixed opioid agonists-antagonists, inhaled nitrous oxide, and acetaminophen.[53] It should be noted that nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) are avoided because of lack of effectiveness during labor and the potential adverse effect of premature closure of the fetal ductus arteriosus.[54],[55] See Table 10.6a for an overview of classes of medications commonly administered to provide comfort during labor and delivery.

Table 10.6a. Medications Commonly Administered During Labor and Delivery to Promote Comfort

| Medication Class | Description | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Opioids |

|

|

| Ultra-Short-Acting Synthetic Opioid |

|

|

| Opioid Agonist-Antagonist |

|

|

| Nitrous Oxide |

|

|

| Acetaminophen |

|

|

Safe medication administration is an important component of nursing care. The nurse provides health teaching on medications and their side effects, assesses the client and fetus before administering medications, and then monitors and documents the effectiveness of medications per agency policy.

Considerations before administering analgesics are maternal clinical status, the stage of labor, and how the fetus is responding to labor and contractions. Prior to administering analgesics, the nurse assesses and documents maternal vital signs, cervical dilation, and stage of labor. Maternal vital signs should be stable and within normal limits before administration of analgesics. All analgesics cross the placenta, so fetal well-being should also be assessed before administration of analgesics. The fetal heart rate should be a reassuring pattern with FHR between 120-160. Side effects of analgesics vary based on the specific analgesic administered and can affect the mother, the fetus, or slow down labor.

Analgesics are typically administered intravenously (IV) to provide fast pain relief to the laboring client. By giving the medication over four or five contractions, it can decrease fetal exposure to the medication. However, IV analgesics also reach the fetus quickly and stay in the fetal cardiovascular system longer. If the fetus is born while the analgesic is still circulating, depressed respirations may be present. The nurse’s role during administration of analgesics during labor includes continuous assessment of both the client and the fetus and identification of the benefit versus risk of the analgesic for the client and fetus. For example, if an opioid is prescribed for labor pain, but the nurse knows that birth is imminent and that an opioid can cause neonatal respiratory depression, the nurse may use clinical judgment and withhold administration of an opioid at that point during labor.[56]

Opioids

Opioids are commonly used for pain relief during labor because they are widely available, easy to use, and are relatively inexpensive. Opioid medications bind to opioid receptors throughout the body. Opioids cause maternal side effects, including nausea, vomiting, pruritus, sedation, and respiratory depression. The nurse teaches clients about potential side effects and the importance of calling for assistance when getting out of bed. In addition, opioids cross the placenta and may lead to reduced fetal heart rate variability, reduced baseline fetal heart rate, neonatal respiratory depression, lower Apgar scores, and neurobehavioral alterations, causing decreased early breastfeeding (i.e., the newborn may be sleepier and less likely to suck).[57]

Some institutions require continuous pulse oximetry when administering opioids during labor to monitor for respiratory depression. Naloxone, an opioid antagonist, is used to treat maternal respiratory depression and may also be used to treat newborns who were exposed to opioids before birth who exhibit cardiorespiratory or neurologic depression.[58],[59]

There are several types of opioids that may be prescribed during labor:

- Fentanyl is a fast-onset and short-acting opioid commonly used to treat severe labor pain. It can be administered intravenously or through an epidural catheter.

- Tramadol inhibits norepinephrine and serotonin reuptake, as well as binds to opioid receptors, resulting in an inhibitory effect on pain transmission in the spinal cord. Research shows that tramadol provides effective analgesia without maternal and neonatal respiratory depression.[60]

- Remifentanil is an ultrashort-acting synthetic opioid with a rapid onset of approximately one minute. It crosses the placenta but undergoes rapid fetal elimination. It is typically administered via a patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) pump, but due to adverse effects of respiratory depression, continuous pulse oximetry and 1:1 staffing ratio of nurse to client is required for safety.[61]

- Butorphanol and nalbuphine are opioid agonist-antagonists that are associated with less neonatal respiratory depression. They can be administered intramuscularly or intravenously. Because of the antagonist property of these medications, clients who are dependent on opiates can experience withdrawal symptoms, so the nurse should assess the client’s history of substance use prior to administration of these medications.[62]

- Meperidine, an opioid once widely used to treat labor pain, is now rarely used in the United States due to adverse effects, based on recommendations from The Joint Commission.[63]

Nitrous Oxide

Nitrous oxide (N2O) is an inhaled analgesic that releases endogenous opioids and stimulates opioid receptors. A commonly used blend is a combination of 50% N2O with 50% oxygen that is self-administered by the client using a face mask. Timing of administration with uterine contractions is important because the onset of analgesic effect is 30 to 60 seconds. N2O is rapidly cleared from the blood of the mother and the fetus within five minutes after cessation and does not affect labor progress, making it safe to use throughout labor. Side effects include nausea, dizziness, and drowsiness.[64]

Nitrous oxide is not a strong analgesic, so laboring clients may still be aware of labor pain. However, many clients find that N2O helps them relax during labor. Because it is self-administered, a client can decide how much medication to use or later decide to stop using it and try another method of pain relief. A systematic review concluded that N2O inhalation improved satisfaction in women despite having a negligible analgesic effect for labor pain.[65],[66]

Acetaminophen

Acetaminophen IV can be used for moderate pain during labor. Research indicates similar effectiveness compared with IV opioids with fewer maternal and fetal adverse effects.[67] Side effects associated with IV administration of acetaminophen include nausea, vomiting, constipation, pruritus, and abdominal pain. Administration of acetaminophen in doses higher than recommended may result in hepatic injury, including the risk of liver failure and death. Acetaminophen passes through the placental barrier and is also present in breastmilk, with few reported adverse fetal reactions.[68],[69]

Other Medications Used to Promote Comfort During Labor

Antiemetics

Promethazine is an antiemetic that was historically administered in conjunction with opioids to treat nausea and vomiting during labor. It causes drowsiness and can help the laboring person sleep. Maternal side effects include drowsiness, nervousness, restlessness, and dry mouth. It can decrease fetal heart rate and cause irritability, excitement, and inhibited platelet aggregation in exposed neonates. It is a Category C medication, meaning it should only be used if the benefits outweigh the risks because it may decrease the fetal heart rate. Routes include oral, rectal, intramuscular (IM), and intravenous (IV). The nurse should be aware of the caustic nature of the medication and should give IM injections deep into the muscle. When administering promethazine IV push, the medication should be diluted and administered slowly over five to ten minutes.[70],[71],[72]

Ondansetron is an antiemetic that blocks serotonin and may be prescribed to treat nausea and vomiting during labor or after a cesarean section. It can be administered as an oral disintegrating tablet, an oral tablet that can be swallowed, intramuscularly, or intravenously. Maternal adverse effects include QT prolongation and serotonin syndrome when taken with other medications that affect serotonin levels such as fentanyl, tramadol, SSRIs, SNRIs, MAOIs, or lithium. Ondansetron is a Category B medication, meaning animal studies have failed to demonstrate a risk to the fetus, but there are no adequate and well-controlled studies in pregnant women. It is not known whether ondansetron is present in human milk.[73],[74]

Anxiolytics

Hydroxyzine is an anxiolytic with antihistamine properties, causing drowsiness and feelings of calmness. Hydroxyzine may be prescribed during the early phase of labor to relieve anxiety and allow the person to rest until active labor begins. It is not normally used during active labor. Side effects include dry mouth, constipation, dizziness, and headache. Hydroxyzine is contraindicated in clients with prolonged QT interval and arrhythmias. Hydroxyzine can be administered orally and intramuscularly in a large muscle but should not be administered intravenously or subcutaneously because it can cause tissue/vessel necrosis, gangrene, and thrombus. Nurses educate laboring clients that they will feel relaxed and sleepy, but that hydroxyzine is not a pain reliever.[75],[76]

Benzodiazepines (such as midazolam) may be used for sedation during childbirth. Midazolam is preferred because it is nonirritating to veins and has a short duration of action.[77]

Anesthetics During Labor and Delivery

Anesthetics block nerves that transmit impulses to the brain and produce a loss of sensation. Different types of local, regional, or general anesthetics may be administered by health care providers, anesthesiologists, or nurse anesthetists during labor or delivery:

- Local anesthetics: Local anesthetics such as lidocaine or bupivacaine may be administered after vaginal delivery to repair perineal tears or episiotomies.

- Regional anesthesia: Several types of regional anesthesia are used during labor and delivery, such as the following:

- A pudendal block is a type of regional anesthesia caused by injection of a local anesthetic into the pudendal nerve that provides sensation to the perineum, anus, vulva, and clitoris. This block is helpful when a third- or fourth-degree laceration repair is required or if the use of forceps or a vacuum extractor is necessary during labor. This local anesthetic block does not require special monitoring by the nurse.

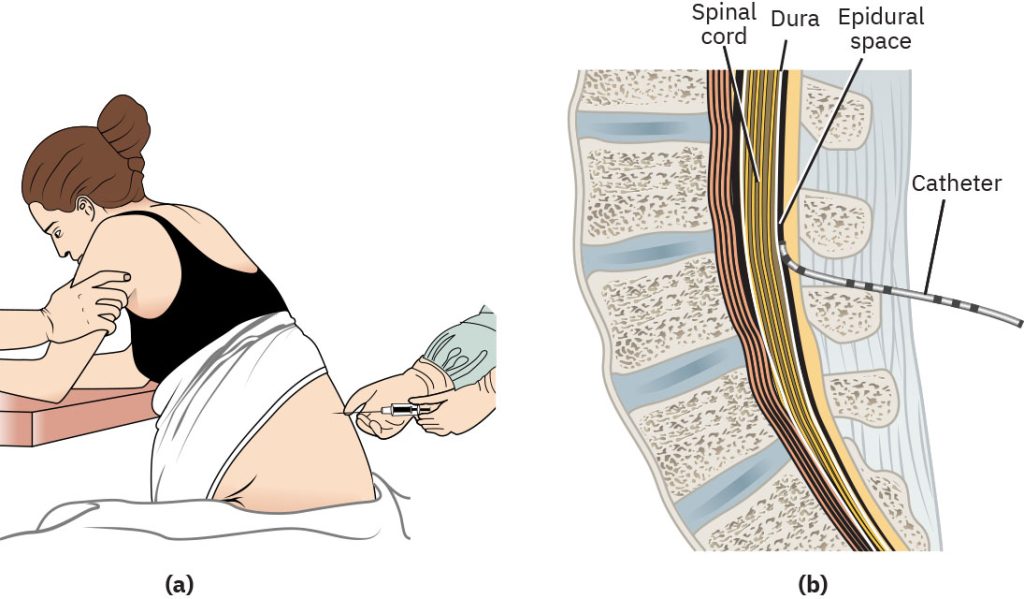

- An epidural is an example of regional anesthesia that is commonly used during labor. During an epidural, a local anesthetic and an opioid are continuously infused through a catheter placed into the epidural space around the spinal nerves to block pain. Epidurals are further discussed in the following subsection.

- A spinal block is commonly used during cesarean sections. It involves injecting a local anesthetic and opioid into the third, fourth, or fifth lumbar space into the subarachnoid space, but a catheter is not inserted for further medication to be infused (as is done during an epidural). The effect is almost immediate and typically provides pain relief for approximately the first 24 hours postpartum. The lack of sedation or drowsiness allows the client to be alert during the birth of their baby. The risks of spinal anesthesia are explained to the client by the anesthesiologist and include hypotension, spinal headache, respiratory depression, nausea, and itching.[78]

- General anesthesia is typically only used during emergent cesarean sections when there is urgent need to deliver the fetus quickly and regional anesthetics are not effective. It causes loss of consciousness of the mother and also affects the fetus.

See Table 10.6b for a comparison of epidural, spinal, and general anesthesia used during labor and childbirth.

Table 10.6b. Comparison of Anesthesia Used During Labor and Childbirth[79]

|

|

Epidural | Spinal | General |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placement | Epidural space | Cerebrospinal fluid of spinal cord | Systemic |

| Area of Anesthesia | Abdomen, pelvis, legs | Abdomen, pelvis, legs | Entire body |

| Level of Pain Management | Pain relief with sensation | Complete pain relief and loss of sensation | Pain relief with loss of consciousness and motor control |

| Movement | Some muscle control | No muscle control | No muscle control |

| Use in Surgery | Yes, if dosage is increased above labor dosage | Yes | Yes |

| Onset | 10–20 minutes | Immediate | Immediate |

| Duration | Long lasting with continuous infusion | Approximately 2 hours with pain relief up to 24 hours | Controlled by anesthesia provider during duration of surgery |

Epidural Anesthesia

Upon the client’s admission in labor, the nurse assesses their desire for a possible epidural. If an epidural is desired, the nurse obtains a prescription from the health care provider and reviews agency policy regarding epidurals. Agency policy outlines required monitoring before, during, and after an epidural infusion, nursing actions related to administering a new epidural infusion bag, and discontinuing the infusion.[80]

Once the laboring client has met the criteria for an epidural according to the provider order, the nurse notifies the anesthesia provider, who educates the client on risks and benefits. Informed consent is obtained from the client. The nurse reviews the admission labs and reports the platelet count to the anesthesia provider. If platelets are below normal (less than 150,000), there is an increased risk for hemorrhage in the epidural space. The anesthesia provider will inform the nurse if the client is not eligible for an epidural for labor due to contraindications such as the following[81]:

- Allergy to the local anesthetic

- Coagulopathy

- Infection

- Hypovolemia

- Valvular heart disease

- Severe left ventricular outflow obstruction

- Neurological disease

During an epidural, a local anesthetic (bupivacaine) and an opioid (fentanyl) are infused through a catheter placed into the epidural space around the spinal nerves to block pain from T10 to S5. See Figure 10.47[82] for an illustration of epidural placement. Obese and severely obese laboring persons may have complications during placement of epidural or spinal anesthetics due to difficulty in locating the correct anatomic space for the administration of medication. The anesthesia provider may use a special, longer needle to penetrate the excess adipose tissue and enter the epidural space.[83]

The nurse explains to the laboring client the need to continuously monitor their vital signs and the FHR when receiving an epidural. An automatic blood pressure cuff, pulse oximeter, and continuous fetal monitor are placed on the client. The well-being of both the laboring person and the fetus is confirmed prior to epidural placement. Because hypotension is a side effect of epidural anesthesia, an IV fluid bolus of 500 to 1,000 mL of lactated ringer’s or normal saline is started 10 to 60 minutes prior to epidural insertion. Prior to epidural insertion, the nurse evaluates the vital signs, stage of labor, cervical change, contraction pattern, and FHR. The nurse may also assist the client to the bathroom to void or place an indwelling catheter as prescribed prior to insertion of the epidural because they will no longer be able to get out of bed after the epidural.[84]

The nurse provides the client with health teaching regarding epidurals, including the loss of feeling in the abdomen, perineum, and legs and that they will no longer be able to ambulate until the effects of the anesthesia have worn off. Fall precautions are reinforced, and the bed is kept low with the side rails up after the epidural is placed. Common side effects are reviewed, including mild itching, nausea, and back pain after birth at the epidural site. Prescribed antiemetics and antihistamines can be administered to reduce these side effects. The nurse also explains that epidural analgesia can be an effective method of pain relief during labor, but technical failure of the epidural is possible. This means the epidural may not effectively relieve pain, due to a variety of reasons, including incorrect placement of the epidural, epidural catheter migration, or incomplete nerve blocking resulting in minimal, incomplete, or asymmetrical analgesic relief. As a result, the client may require implementation of additional alternative pain-relieving methods, including nonpharmacologic interventions and systemic medications.[85],[86]

Immediately prior to the epidural insertion, the nurse positions the client in the seated or side-lying position with the back in a C-position to open the spaces between the vertebrae. The nurse or partner assists the client to maintain the appropriate position during epidural insertion, and the nurse monitors vital signs and FHR. After insertion of the epidural catheter, the anesthesia provider injects medication as a test dose. The nurse notes the time and any side effects reported by the client. The epidural catheter is taped into place, and the anesthetic can be set to a continuous infusion, along with client-controlled periodic boluses.

After the epidural catheter is taped into place, the nurse assists the client into a supine position with a wedge under one hip to displace the uterus off the vena cava and aorta and prevent aortocaval compression syndrome. Vital signs and FHR are monitored according to agency policy, typically every 5 to 15 minutes after insertion. The nurse also assesses the client for pain control, hypotension, respiratory depression, level of consciousness, and paresthesia. Less common side effects include bradycardia, infection, and nerve injury. Epidural anesthesia is also associated with increased risks for labor augmentation with oxytocin, operative vaginal birth, and increased length of labor; however, research suggests these outcomes are dependent on the dosing of epidural medication and the practices of the obstetric care provider.[87] If the laboring client becomes hypotensive, the nurse notifies the health care provider for an anticipated order for an IV fluid bolus. If an IV fluid bolus is contraindicated or it is not effective, a vasopressor such as ephedrine may be prescribed to increase the client’s blood pressure. During the hypotensive episode, the nurse also monitors FHR for late decelerations and fetal bradycardia because hypotension can decrease uteroplacental perfusion and fetal oxygenation.

Bladder function is affected by anesthesia, so the nurse monitors for urinary retention when a client is receiving epidural infusion. Depending on the stage of labor, cervical dilation, and agency policy, the nurse may perform bladder scans, intermittent catheterization, or insert an indwelling urinary catheter during the first stage of labor.

See the following supplementary YouTube[88] video on epidurals: Pain Management Series: Epidurals for Pain Relief During Labor.

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Trachsel, L. A. A., Munakomi, S., & Cascella, M. (2023). Pain theory. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545194/ ↵

- “Gate_Theory_Circuit_Mechanism” by John.Tuthill is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Trachsel, L. A. A., Munakomi, S., & Cascella, M. (2023). Pain theory. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545194/ ↵

- Trachsel, L. A. A., Munakomi, S., & Cascella, M. (2023). Pain theory. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545194/ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Trachsel, L. A. A., Munakomi, S., & Cascella, M. (2023). Pain theory. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK545194/ ↵

- Jones, L. E., Whitburn, L. Y., Davey, M.-A., & Small, R. (2015). Assessment of pain associated with childbirth: Women׳s perspectives, preferences and solutions. Midwifery, 31(7), 708–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2015.03.012 ↵

- Jones, L. E., Whitburn, L. Y., Davey, M.-A., & Small, R. (2015). Assessment of pain associated with childbirth: Women׳s perspectives, preferences and solutions. Midwifery, 31(7), 708–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2015.03.012 ↵

- Whitburn, L. Y., Jones, L. E., Davey, M. A., & McDonald, S. (2019). The nature of labour pain: An updated review of the literature. Women and Birth: Journal of the Australian College of Midwives, 32(1), 28–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.wombi.2018.03.004 ↵

- Rantala, A., Hakala, M., & Pölkki, T. (2022). Women's perceptions of the pain assessment and non-pharmacological pain relief methods used during labor: A cross-sectional survey. European Journal of Midwifery, 6(21), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.18332/ejm/146136. ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez,O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez, O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “changing positions" by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “ae7c0d3cfbe4a4589be493f04a9eca1015” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/17-1-nonpharmacological-pain-management ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Oh Baby! Fitness. (2011, January 28). Pelvic tilt - Pregnancy exercise - Oh baby! Fitness [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=moa4h-rjuNE ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez,O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- “40cf326a229c50e6b11306165d5367c74355999f” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/17-1-nonpharmacological-pain-management ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Fearless Momma Birth. (2020, March 16). 5 BEST labor massage for pain management! [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=abDfsx2rNr4 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “273a152bc0842635c05391b13daf4023fcfeedf9” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/17-1-nonpharmacological-pain-management ↵

- “b275bdbf80b21341b1a1561dff2d8bf91b58caaf” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/17-1-nonpharmacological-pain-management ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez, O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez, O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- Mater. (2020, November 5). Using TENS for labour pain | Physiotherapy | Mater mothers [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=40lv-WANbtM ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez, O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez, O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Reale, S. (2024). Pharmacological management of pain during labor and delivery. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Reale, S. (2024). Pharmacological management of pain during labor and delivery. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez, O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- Reale, S. (2024). Pharmacological management of pain during labor and delivery. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez, O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez, O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez, O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- Ronel, I., & Weiniger, C. F. (2019). Non-regional analgesia for labour: Remifentanil in obstetrics. BJA Education, 19(11), 357–361. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bjae.2019.07.002 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Harrison, L. R., Arnet, R. E., Ramos, A. S., Chinga, P. A., Anthony, T. R., Boyle, J. M., McCall, K. L., Nichols, S. D., & Piper, B. J. (2022). Pronounced declines in meperidine in the US: Is the end imminent? Pharmacy, 10(6), 154. https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmacy10060154 ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez, O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez, O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- American Pregnancy Association. (n.d.). Nitrous oxide during labor. https://americanpregnancy.org/healthy-pregnancy/labor-and-birth/nitrous-oxide-labor/ ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez,O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- Gerriets, V., Anderson, J., Patel, P., et al. (2024). Acetaminophen. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK482369/ ↵

- Daily Med. (2024). Acetaminophen. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=54f408da-4a92-472b-b76f-b4924175ca51 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Solt, I., Ganadry, S., & Weiner, Z. (2002). The effect of meperidine and promethazine on fetal heart rate indices during the active phase of labor. The Israel Medical Association Journal: IMAJ, 4(3), 178–180.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11908257/ ↵

- Drugs.com. (2023). Promethazine pregnancy and breastfeeding warnings. https://www.drugs.com/pregnancy/promethazine.html ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- National Institutes of Health. (2023). Ondansetron hydrochloride injection. DailyMed. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=01d69f4d-eddf-4fc8-820b-832f11f2e3c0 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Daily Med. (2024). Hydroxyzine. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=8af7e5ce-d9d9-44cc-9f2f-4ddbc89e758a ↵

- Reale, S. (2024). Pharmacological management of pain during labor and delivery. UpToDate. https://www.uptodate.com/ ↵

- Jones, L. E., Whitburn, L. Y., Davey, M.-A., & Small, R. (2015). Assessment of pain associated with childbirth: Women׳s perspectives, preferences and solutions. Midwifery, 31(7), 708–712. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2015.03.012 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Zuarez-Easton, S., Erez, O., Zafran, N., Carmeli, J., Garmi, G., & Salim, R. (2023). Pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic options for pain relief during labor: An expert review. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 228(5), S1246-S1259. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2023.03.003 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “5f84d98bf309c317f2677a700603ea5d1045d45a” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/17-3-anesthesia ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Arendt, K., & Segal, S. (2008). Why epidurals do not always work. Reviews in Obstetrics & Gynecology, 1(2), 49–55.https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/18769661/ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Evidence Based Birth. (2018, February 2). Pain management series: Epidurals for pain relief during labor [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gB5uKFbxGcc ↵

Theory exploring that pain perception is a dynamic process influenced by physical, psychological, and sociological factors and that a mechanism in the dorsal horn of the spinal column serves as a “gate” that either allows or prevents pain signals from reaching the brain.

Forceps- or vacuum-assisted birth.

Use of essential oils to aid in relaxation.

The client centers their attention on a picture or an object in the room and concentrates on breathing through the contraction.

Uses the mind-body connection to focus the client’s awareness on a positive safe place using all of their senses.

A slow, deep inhalation through the nose and exhalation through the mouth.

The process of expanding the abdomen on inhalation and then exhaling and relaxing the abdomen.

The process of expanding the chest while inhaling and then letting the chest fall when exhaling.

Rhythmic use of vowel sounds are used to keep the throat open and relaxed.

A pattern of breathing using two short breaths and one long breath that sounds like “hee-hee-hoo.”

The client inhales deeply and then holds their breath while bearing down and pushing and counting to ten.

The client inhales deeply and then slowly exhales as they bear down to push.

Using water to provide pain relief during labor.

The immersion of the client in water during the second stage of labor and delivery of the fetus.

A physical manipulation of tissue that can be provided in different ways, depending upon the preference of the laboring client.

Light stroking massage using the tips of the fingers in slow, long strokes on the client’s abdomen in rhythm with contractions.

The act of providing sustained firm pressure to the client’s back, hips, sacrum, or other joints.

Procedures typically used by midwives to relieve back pain during labor based on the gate control theory of pain.

The application of electrical currents to the surface of the skin which blocks pain signal transmission and releases endorphins.

A process which cultivates a client’s sense of control over the labor process by promoting the feeling that their mind has control over their body.

Works by inhibiting neuronal communication between the sensory cortex, amygdala, and limbic system and decreasing the conduction of pain sensations.

Used in traditional Chinese medicine, involves the insertion of fine needles into different areas of the body to address imbalances of energy (in the form of qi).

Based on the same principle as acupuncture but involves the therapist using their hands and fingers to stimulate specific body points, rather than needles.

Medication which temporarily induces a loss of feeling or awareness.

Induces a loss of feeling in a small area of the body.

Induces a loss of feeling in a specific part of the body.

Induces a loss of feeling and complete loss of awareness which feels like a very deep sleep.

Block nerves that transmit impulses to the brain and produce a loss of sensation.

A type of regional anesthesia caused by injection of a local anesthetic into the pudendal nerve that provides sensation to the perineum, anus, vulva, and clitoris.

A local anesthetic and an opioid are continuously infused through a catheter placed into the epidural space around the spinal nerves to block pain.

Involves injecting a local anesthetic and opioid into the third, fourth, or fifth lumbar space into the subarachnoid space, but a catheter is not inserted for further medication to be infused (as is done during an epidural).