10.4 The P’s of Labor

When labor begins, there are several aspects that must work in synchrony for vaginal birth to occur, such as the force of labor, the pelvic anatomy, the fetal influence on labor, the physical positions involved, and the pregnant woman’s mental status. These aspects can be remembered using the mnemonic called the 5 P’s of Labor that include Power, Passageway, Passenger, Positioning, and Psyche. Being knowledgeable about the 5 P’s of labor helps nurses understand the factors that must work together for a successful and safe vaginal birth. Additionally, this knowledge allows nurses to teach clients who must make informed decisions regarding operative vaginal birth and cesarean birth options. Each of the 5 P’s is further discussed in the following subsections.

Power

Power refers to the strength of the uterine contractions that move the fetus through the pelvis during labor, as well as the maternal pushing efforts during delivery of the fetus. Uterine contractions are a pattern of rhythmic tightening and relaxation of smooth muscle fibers of the uterus that cause downward pressure on the fetus. As the fetal head moves through the maternal pelvis, it applies pressure to the cervix, leading to cervical effacement and dilation. After the cervix is completely dilated, contractions help push the baby out of the uterus.[1]

Nurses assess the uterine contraction pattern to determine the progression of labor and to monitor for potential complications. DIF is an acronym used to assess uterine contractions and refers to Duration, Intensity, and Frequency. See Figure 10.5[2] for an illustration of the duration, intensity, and frequency of contractions.

Duration refers to the time from the beginning to the end of one contraction and is indicated in light blue in Figure 10.5. Intensity refers to the strength of the contraction and is indicated in dark blue. Intensity is described as mild, moderate, or strong. Increment refers to the buildup of the contraction, acme refers to the peak of a contraction, and decrement is the gradual lessening of the contraction. Frequency refers to the time from the start of one contraction to the start of the next contraction. Duration, interval, and frequency can be measured based on the mother’s report of each contraction or by external or internal monitoring devices. Interval refers to the time of uterine relaxation between contractions and is indicated in light orange.[3]

Adequate Uterine Contractions

Adequate uterine contractions have enough duration, strength, and frequency to cause the cervix to dilate and efface and move the fetus through the maternal pelvis. Insufficient uterine contraction patterns, also referred to as dystocia, do not cause cervical dilation, effacement, or fetal descent. Effacement is the gradual thinning and shortening of the cervix and is measured from 0 percent to 100 percent. Dilation is the gradual opening of the cervix, measured in centimeters (cm), from 0 to 10 cm.[4] Fetal station refers to the level of the fetal presenting part in relation to the maternal ischial spines and is measured in centimeters from -5 cm to 5 cm, where 0 cm means the fetal head is level with the maternal ischial spines. See Figure 10.6[5] for an illustration of effacement, dilation, and fetal station.

See Figure 10.7[6] for a more detailed look at fetal station. In this image, the fetal station is 0 because the distal fetal head is at the level of the ischial spines of the maternal pelvis, as indicated by the orange line. This is also referred to as engagement, meaning the widest part of the fetal presenting part has passed through the pelvic inlet and is at the level of the maternal ischial spines.

Measuring Uterine Contractions

Contraction intensity can be assessed externally by palpating the contracted uterus or by electronic monitoring. When palpation is used, the nurse places their fingertips on the client’s abdomen over the fundus (i.e., the uppermost part of the uterus) to assess the intensity of the contraction.

Electronic monitoring may be external or internal. External continuous monitoring is obtained using a tocodynamometer (i.e., a pressure sensitive device) that is placed on the abdomen over the fundus to measure frequency, duration, and relative intensity of contractions. The duration and frequency are typically measured accurately by a tocodynamometer, although measurement of the intensity of the contractions is less accurate than internal continuous monitoring.

Internal continuous monitoring is obtained by the placement of an internal pressure catheter into the uterus. The internal pressure catheter measures resting tone of the uterus and intensity of contractions in millimeters of mercury (mmHg). Resting uterine tone is between 10-12 mm Hg. Contractions during labor can range in intensity during the acme from 40 mmHg (mild) to 70 mmHg (strong). During pushing, contraction intensity may reach 100 mmHg.

Monitoring measures uterine contractions, as well as fetal heart rate. Measurements from external and internal continuous monitoring can appear on monitors, as well as on paper tracings. Figure 10.8[7] is an illustration of fetal heart rate (FHR) tracing obtained by external monitoring. The top half of the tracing indicates the FHR wave, with the middle column of the tracing being numbers reflecting the fetal heart rate. Normal FHR range is from 110 to 160 beats per minute (bpm). In this illustration, the FHR is between 150 to 160 bpm, and there is no slowing of the heart rate between uterine contractions. The bottom half of the illustration shows the uterine contractions measured by the tocodynamometer. Each small rectangle represents ten seconds. The middle column shows the intensity of the contraction in mmHg. In this tracing, the beginning and end of each contraction, as indicated by red arrows, has a duration of about one minute (60 seconds), an interval between contractions of about two minutes (110-120 seconds), and a frequency of contractions of about one every three minutes (170-180 seconds). The acme of the contractions is about 50 mm Hg.

Additional information about interpreting FHR monitoring is discussed in the “Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring” section.

Pushing Efforts

The power of labor also refers to the second stage of labor when the woman begins pushing to deliver the fetus. Pushing efforts are classified as effective or ineffective based on progress in fetal station. The power of pushing can be affected by several factors, including maternal muscular strength, fatigue, epidural anesthesia that causes decreased sensation of the urge to push, optimal or suboptimal fetal positioning for vaginal birth, and the strength of the uterine contractions to push the fetus through the passageway.[8]

Passageway

The second P of labor is called passageway and includes the maternal pelvic structures of bone and soft tissues. Relaxin, one of the hormones that prepares the woman’s body for birth, softens the ligaments of the pelvis, which then causes a shift in the pelvic floor anatomy to accommodate the changes in diameter needed for birth. The passageway can also be affected by pelvic shape and pelvic floor health.[9]

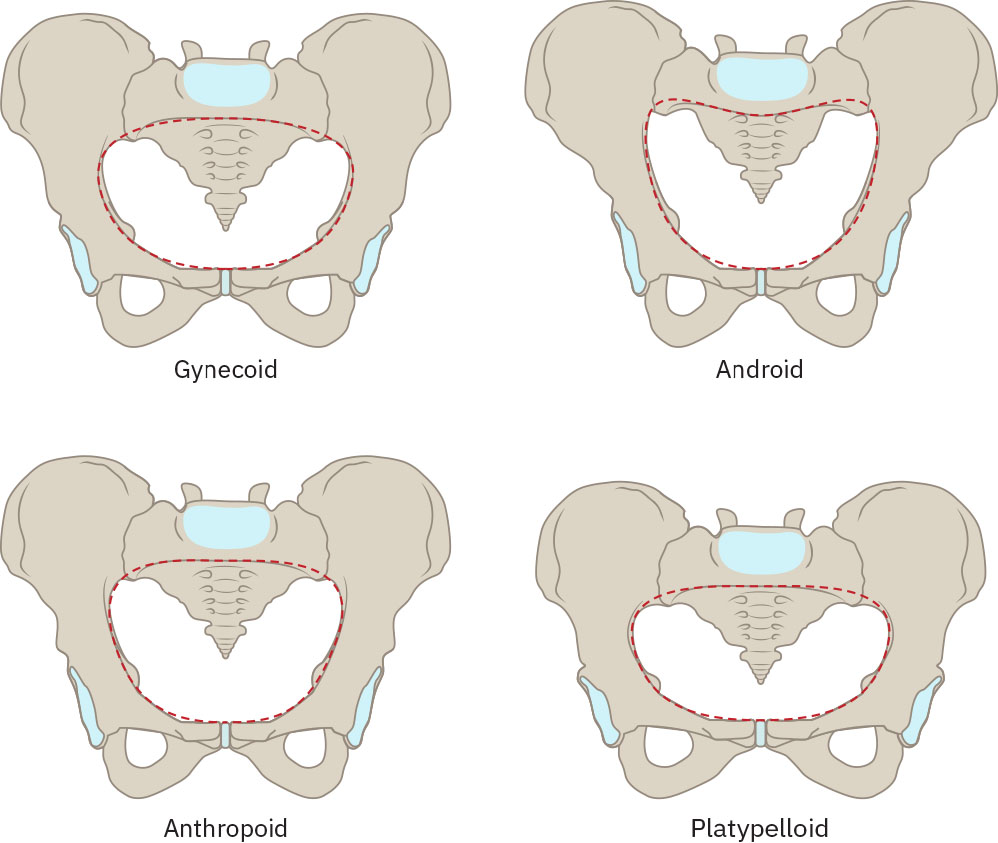

Traditionally, the overall shape of the pelvis and pelvic diameters are categorized into four pelvis shapes: gynecoid, android, anthropoid, and platypelloid. These shapes are determined by clinical pelvimetry or by the health care provider digitally measuring the pelvic structures during a vaginal exam. The gynecoid pelvis has a circular inlet that is considered most favorable for vaginal delivery, with less likelihood of prolonged or complicated deliveries. Anthropoid pelvis shapes have a long oval inlet and are associated with occipital posterior deliveries. Platypelloid pelvis shapes have a short oval inlet. Android pelvis shapes have a heart-shaped inlet. Android, anthropoid and platypelloid shapes were historically thought to be associated with complex labors with increased medical interventions, but recent research has shown these shapes do not predict negative birth outcomes or an increased risk for cesarean section. See Figure 10.9[10] for an illustration of these pelvis shapes.[11]

The pelvic floor supports the abdominal cavity for all humans, but during birth it becomes dynamic and serves a crucial function in vaginal delivery. The major pelvic muscles and fascia assist with fetal rotation and fetal descent within the maternal pelvis. The pelvic floor provides support while also allowing stretching over the fetal presenting part to allow passage for birth. Dysfunctional labor can occur when the pelvic floor has too much or too little support for the movement of the fetus through the passageway. For example, previous pelvic floor damage and multiparity can weaken pelvic muscles and cause fetal malpositioning.[12]

Passenger

The third aspect of labor is the fetus, referred to as the passenger. While attention is typically focused on the experience of the laboring woman, fetal factors also affect labor progression, depending on the fetal tolerance of the power and passage, as well as fetal size and its position within the pelvis.[13]

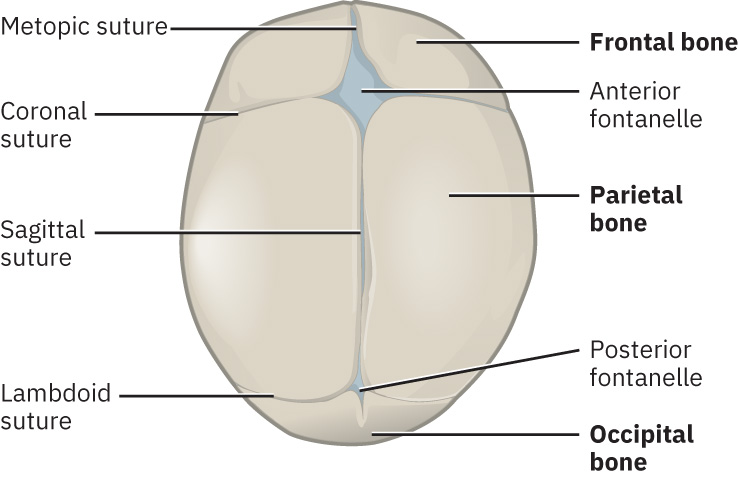

The fetal head is physiologically designed to pass through the maternal pelvis during labor and delivery. The fetal skull has sutures between the bones that are not yet fused and fontanelles that compress. These features allow for significant alteration in the shape of the fetal head during labor and delivery. See Figure 10.10[14] for an illustration of the sutures and fontanelles of the fetal head. Compression of these cranial bones, sutures, and fontanelles during labor and delivery reduces the diameter of the fetal head and facilitates passage through the maternal pelvis in a process called molding.[15]

Molding, as well as fetal lie, fetal presentation, and fetal position, affects the ability of the fetus to pass through the maternal pelvis. The nurse and/or health care provider performs Leopold’s maneuvers to determine the fetal lie based on the location of the fetal head, followed by a vaginal exam to digitally assess fetal presentation and fetal position. An ultrasound may also be ordered to confirm fetal position. Fetal lie, fetal presentation, and fetal position are further described in the following subsections.[16]

Review Leopold’s maneuvers in the “Third Trimester Prenatal Care” section of the “Antepartum Care” chapter.

Fetal Lie

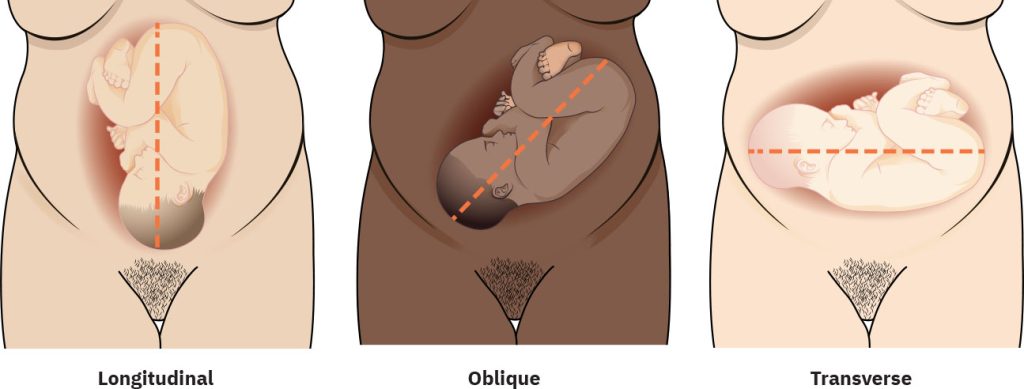

Fetal lie refers to the relationship of the fetal spine to the mother’s spine. See Figure 10.11[17] for an illustration of fetal lie. Fetal lie is either longitudinal or non-longitudinal.

A longitudinal lie refers to the fetal spine lining up vertically with the mother’s spine with the fetal head down in the maternal pelvis. This is also referred to as cephalic presentation and is optimal for vaginal birth.

A non-longitudinal lie means the fetal spine is not lined up vertically with the mother’s spine and includes oblique lie and transverse lie. Non-longitudinal lies may occur due to preterm gestation, grand multiparity (i.e., at least five previous births), abdominal wall laxity, uterine anomalies, or the presence of uterine fibroids.[18]

In an oblique lie, the fetal spine lines up diagonally with the mother’s spine. A fetus in an oblique lie is further described by the location of its presenting part in relation to the maternal abdominal quadrant. For example, the fetal head may be described as being in the mother’s left lower quadrant. An oblique lie can delay the progress of labor due to a lack of pressure on the cervix by the fetal head. A fetus in an oblique lie will often convert to a longitudinal lie during active labor due to increased intrauterine pressure caused by contractions.[19]

In a transverse lie, the fetal spine is horizontal to the mother’s spine, similar to a plus (+) sign. When a fetus is in the transverse lie, the fetal spine is further described to be in the back-down or back-up orientation. Transverse lie is not compatible with vaginal birth and requires maneuvers to change fetal position or a cesarean birth.[20]

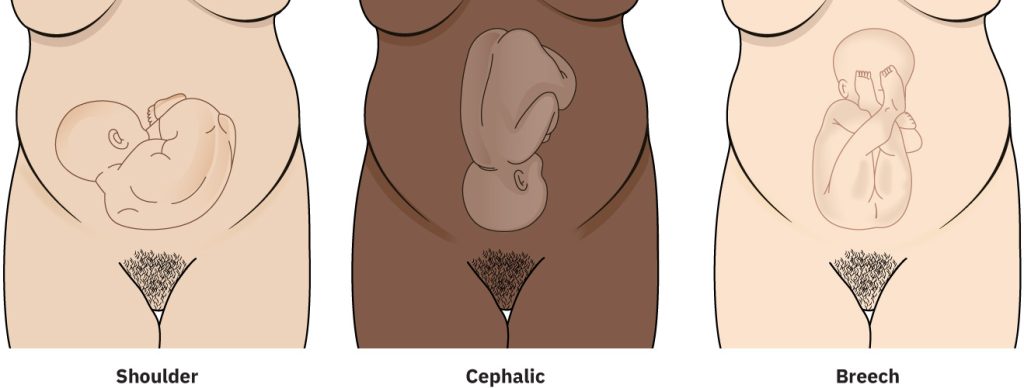

Fetal Presentation

Fetal presentation refers to the fetal part present in the lower part of the uterus, or the presenting part. When the fetal head enters the pelvis first, it is called cephalic presentation. If the fetal buttocks (or legs) enter the pelvis first, it is called breech presentation. If the fetus is in a transverse lie, where the shoulder enters the pelvis first, it is called shoulder presentation. See Figure 10.12[21] for an illustration of cephalic, breech, and shoulder presentations.

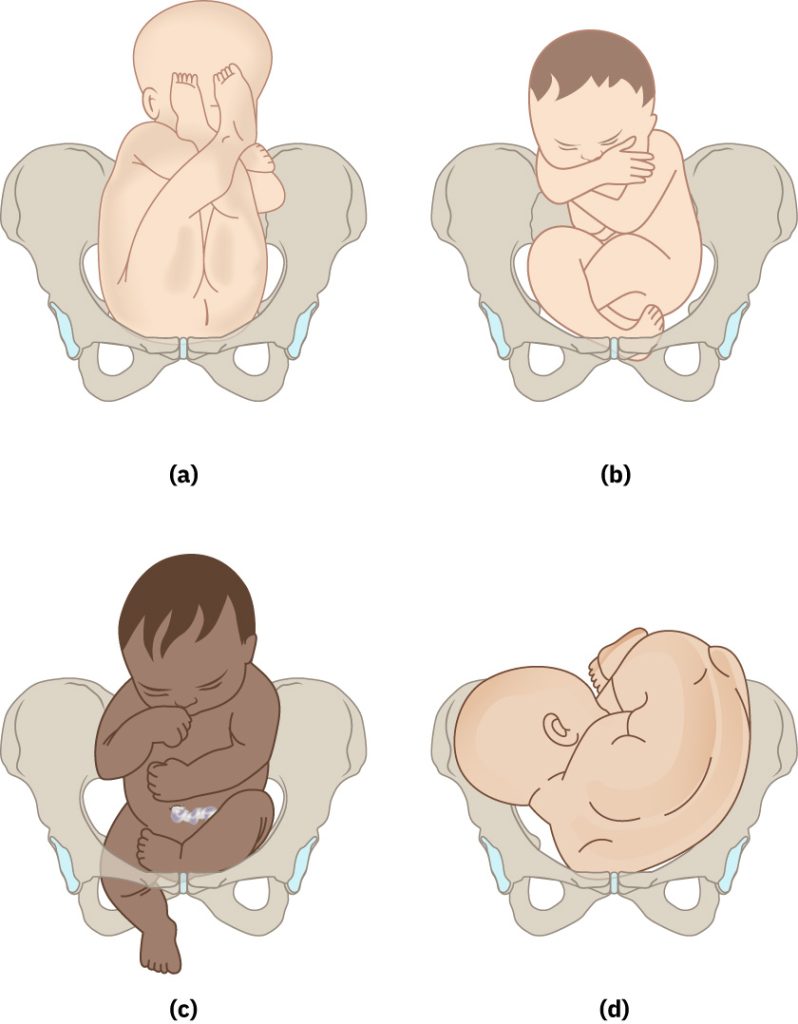

Vertex presentation is the most common type of cephalic presentation, meaning the fetal head is down in the maternal pelvis with its neck flexed and the chin tucked into its chest, thus minimizing the diameter of the fetal head to conform to the maternal pelvis. In most women in labor at term, the fetus presents in a vertex presentation. However, the fetal head may be extended instead of flexed, ranging from mild extension to full extension. Fetal attitude refers to the presence of extension of the fetal head and neck. In brow presentation, the neck is slightly flexed, and the forehead is the presenting part of the fetal head. In face presentation, the neck is fully extended, and the presenting part is the mentum (fetal chin).[22] See Figure 10.13[23] for illustration of vertex presentations with varying degrees of head extension, ranging from normal vertex presentation to face presentation.

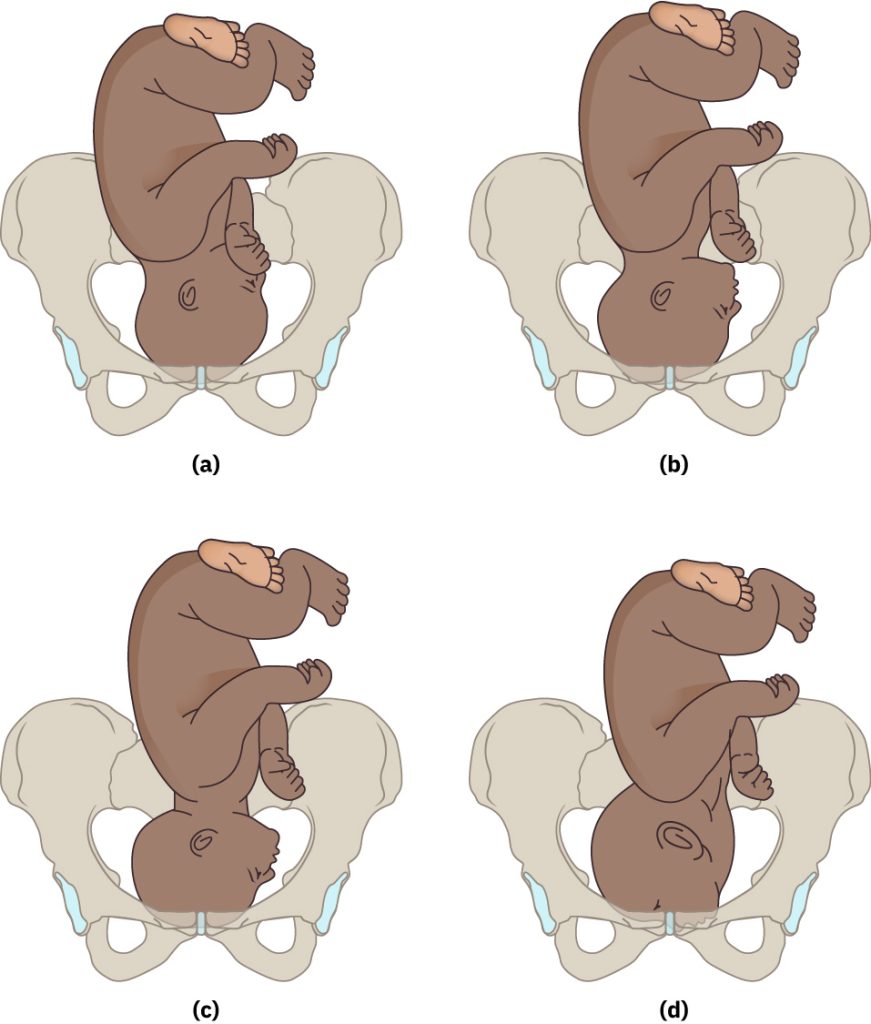

There are several types of breech presentations, including frank breech (bottom first with legs straight up toward head), complete breech (bottom first with legs crossed), footling breech (one leg first), or shoulder presentation (shoulder first). See Figure 10.14[24] for an illustration of various breech presentations.[25]

Fetal Position

Fetal position refers to the relationship of the presenting fetal part to the mother’s pelvic anatomic landmarks.

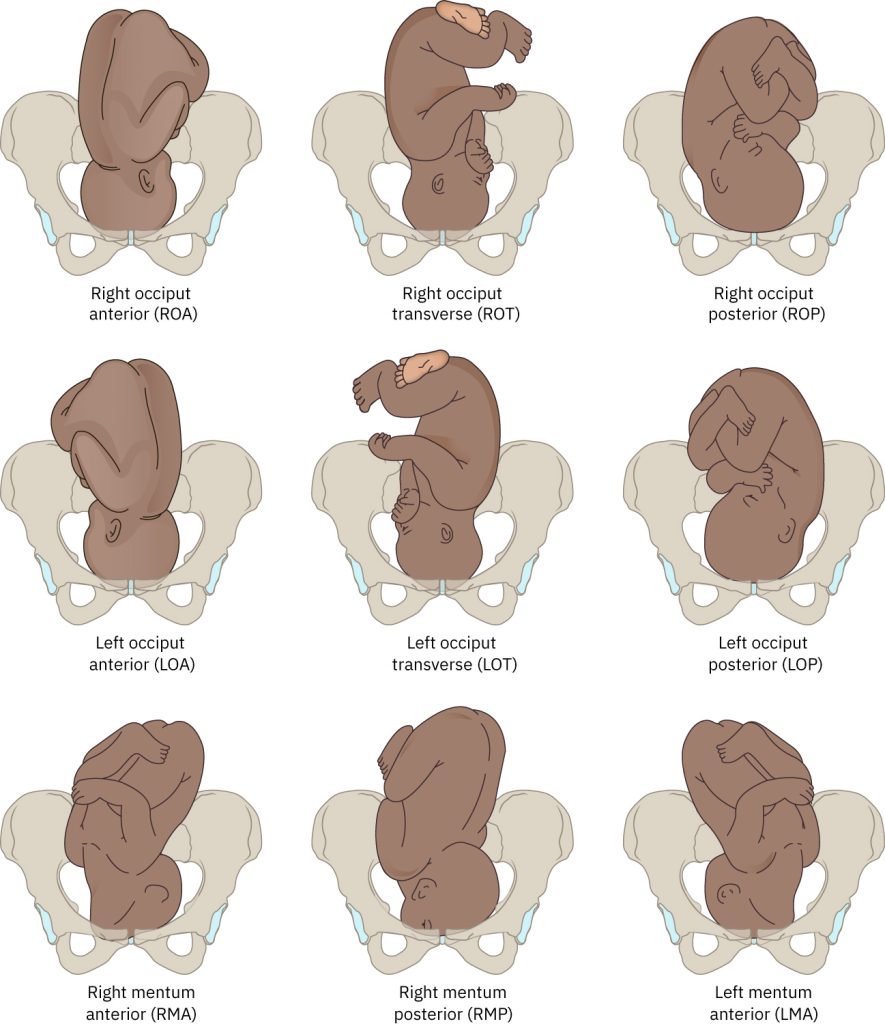

In cephalic presentations, the fetal position is described as occiput anterior, occiput posterior, occiput transverse, mentum anterior, mentum posterior, or mentum transverse.

In occiput positions, the fetal head is down, and the neck is flexed, so the occiput (back of the skull near the occipital bone) is the leading presenting fetal part.

- Occiput anterior positions mean the fetal occiput is close to the maternal symphysis pubis, and the face is pointed towards the mother’s spine. The fetus will also be slightly off-center, with the occiput slightly facing the mother’s left side (called left occiput anterior [LOA]) or the mother’s right side (called right occiput anterior [ROA]). Occiput anterior positions are optimal for vaginal delivery.[26]

- Occiput posterior positions mean the fetal occiput is close to the maternal spine, and the face is pointed toward the maternal symphysis pubis. This position is nicknamed “sunny side up” because the fetal face appears before the occiput during delivery in the lithotomy position. The back of the fetal head slightly faces left or right, called left occiput posterior (LOP) or right occiput posterior (ROP). Occiput posterior positions may be safe for vaginal delivery.[27]

- Occiput transverse (OT) means the fetal head is down and the chin is tucked but the head is lying sideways in the birth canal.[28]

If the fetal head is down but the neck is extended, the fetal mentum (protruding part of the chin) is the leading presenting fetal part.

- Mentum anterior means the fetal chin is facing the mother’s abdomen, either slightly to the right, called right mentum anterior (RMA), or to the left called left mentum anterior (LMA).[29]

- Mentum posterior means the fetal chin is facing the mother’s spine, either facing the right called right mentum posterior (RMP) or to the left, called left mentum posterior (LMP).[30]

- Mentum transverse (MT) means the fetal head is down with the chin facing the spine, but the face is lying sideways in the birth canal.[31]

Consider the meaning of the three letters in the abbreviations discussed in the previous paragraphs regarding fetal position:

- R or L: The first letter indicates the side of the maternal pelvis the fetal presenting part is pointing. For example, in cephalic occiput presentations, R indicates the fetal occiput is pointed to the maternal right side.

- O, M, or S: The second letter refers to the leading fetal presenting part, being the occiput, mentum, or sacrum.

- A, P, or T: The third letter refers to the maternal reference point of the fetal presenting part, being anterior, posterior, or transverse. For example, if the fetal presenting part is closest to the maternal sacrum, it is considered posterior. If the fetal presenting part is closest to the maternal symphysis pubis, it is considered anterior. If the fetal presenting part is lying sideways in the birth canal, it is considered transverse.

See Figure 10.15[32] for illustration of a variety of cephalic fetal positions, including left occiput anterior (LOA), left occiput transverse (LOT), left occiput posterior (LOP), right mentum anterior (RMA), right mentum posterior (RMP), and left mentum anterior (LMA).

For breech presentations, the fetal position is described based on the location of the fetal sacrum in relation to the mother’s spine. For shoulder presentations, the fetal position is described based on the location of the fetal acromion in relation to the mother’s spine.

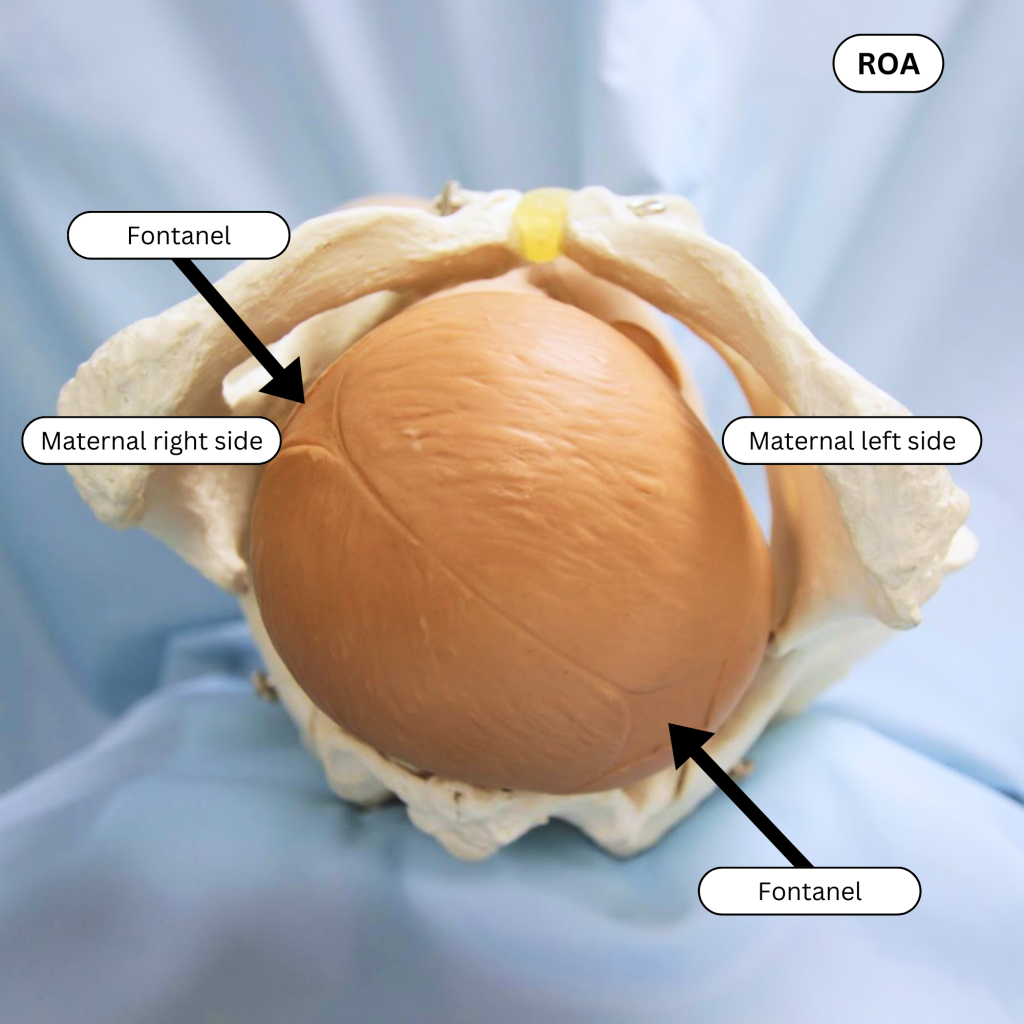

To determine fetal lie, fetal presentation, and fetal position during labor, the health care provider and/or nurse first performs Leopold’s maneuvers. If a fetus is identified to be in the cephalic presentation based on Leopold’s maneuvers, a vaginal examination is performed, and the fetal head is palpated. The sagittal suture, anterior fontanelle, and posterior fontanelle are identified as landmarks, and their positions within the maternal pelvis are used to determine fetal position and fetal attitude. Refer back to Figure 10.11 for an illustration of these fetal head landmarks. The following steps describe the procedure for identification:

- The sagittal suture is identified to determine the orientation of the fetal head in relation to the maternal pelvis (e.g., Is the fetal head located anterior, posterior, or transverse in relation to the maternal pelvis?).

- The sagittal suture is palpated from end to end to identify the posterior and anterior fontanelles.

- The anterior fontanelle presents as a diamond-shaped depression. Four sutures extend from the fontanelle.

- The posterior fontanelle is typically compressed during labor and presents as a triangle-shaped depression. Three sutures extend from the posterior fontanelle and may be overlapping.

- The posterior fontanelle is used to identify the fetal occiput.

- The position and lie of the fetal occiput are described in terms of the maternal sacrum and symphysis pubis and identified as LOA, ROA, LOP, ROP, OT, RMA, LMA, RMP, LMP, or MT.

Diagnosing the exact fetal presentation and fetal position can be challenging. To avoid misdiagnosis, a bedside ultrasound may be performed.

Examples of Identifying Fetal Position

Example 1: ROA

See Figure 10.16[33] illustrating a fetal head in a maternal pelvis when the mother is lying supine. First, note that the fetal head is the presenting fetal part, and it is in a cephalic (head down) position. Then, locate the triangle-shaped posterior fontanelle in the upper right corner of the image. The posterior fontanel indicates the fetal occiput is on the right side (R) of the maternal pelvis, and the occiput is leading the presenting part (O). The fetal occiput is closest to the maternal symphysis pubis, so it is in anterior position (A). Therefore, the fetus is in the right occiput anterior (ROA) position.

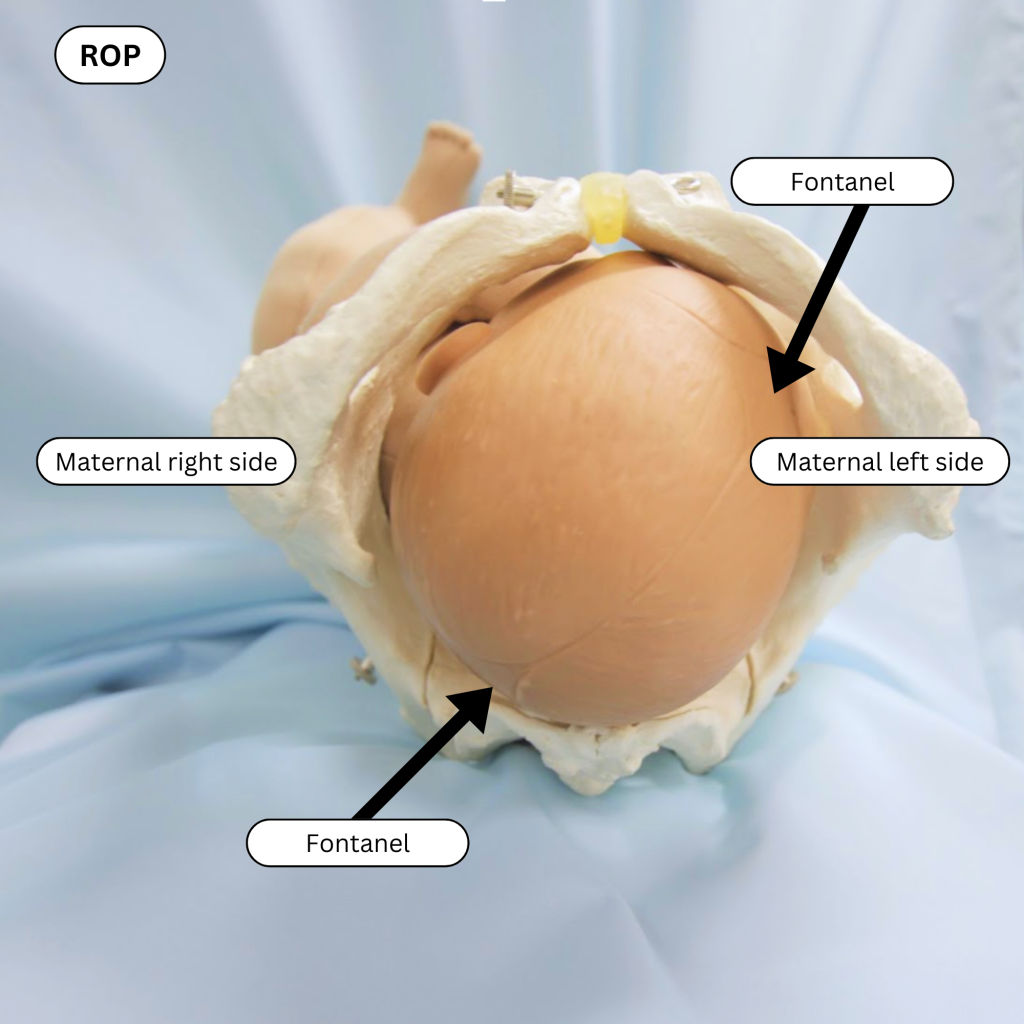

Example 2: ROP

See Figure 10.17[34] illustrating a fetal head in a maternal pelvis when the mother is lying supine. First, note that the fetal head is the presenting fetal part, and it is in a cephalic (head down) position. Then, locate the triangle-shaped posterior fontanelle. The posterior fontanel indicates the fetal occiput is in the lower right (R) of the maternal pelvis, and the occiput is leading the presenting part (O). The fetal occiput is closest to the maternal sacrum (not symphysis pubis), so it is in posterior position (P). Therefore, the fetus is in the right occiput posterior (ROP) position.

View a supplementary YouTube video[35] on types of fetal positions at Types of Fetal Positions – OSCE Guide.

Positioning

Positioning is the fourth P of labor. Labor is a dynamic process that requires adaptation by the maternal pelvis and fetus for progression to occur. Frequent positioning changes by the mother promote normal physiological progression of labor and fetal descent through the pelvis. Continued movement by the mother encourages fetal internal rotational maneuvers that are part of the mechanisms of birth that move the fetus through the maternal pelvis. When a nurse is caring for a laboring client who is experiencing a slow labor or nonreassuring changes in fetal heart rate, the nurse should think, “In what position is the client?” followed by “What position should be tried next?” There are many potential positions for each stage of labor with accompanying reasons why each is recommended.[36]

Nurses consider the client’s cultural beliefs when encouraging position changes. In many cultures, upright birth is traditionally used as depicted in ancient art. However, the lithotomy position is commonly used in hospitals in the United States during delivery. Research indicates the lithotomy position and the associated lack of repositioning may increase risk of pelvic floor dysfunction or injury and increase stress on the fetus during the second stage of labor. If epidural anesthesia is being used, nurses also encourage repositioning to prevent musculoskeletal and nerve injuries that may occur from prolonged use of a single position, especially the lithotomy position with significant hip flexion.

Review various positions used during labor and delivery in the “Stages of Labor” subsection.

Psyche

Psyche is the fifth P of labor. Psyche refers to the psychological emotional state of the mother giving birth and plays an important role during labor and delivery. Nurses create a supportive and positive birthing environment to reduce stress and anxiety for the mother. A quiet room with soft lighting is helpful to reduce environmental stimuli. Nurses may encourage the laboring client to use pleasant aromas; peaceful music; and personal comfort items, such as soft, comfortable fabrics and clothing. The nurse also provides emotional support by providing physical presence and interventions, information, and advocacy.[37]

Prenatal classes are also useful in creating a positive and supportive birth experience. They provide anticipatory guidance on common emotions the mother may experience during labor and delivery, as well as helpful actions by the client’s partner or support person during labor.

Nurses must consider the importance of culture when considering the psyche during childbirth. The Office of Minority Health (OMH), a division of the Department of Health and Human Services, requires culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS) in maternal health care to improve quality of care and reduce disparities. Nurses help ensure CLAS by providing respectful, compassionate, high-quality care that responds to each client’s cultural values, beliefs, and preferences.[38]

- Review cultural competence, culturally sensitive care, and culturally responsive care in the “Diverse Patients” chapter of Open RN Nursing Fundamentals, 2e.

- View a free two-hour e-learning program from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services designed for students and nurses seeking to increase their knowledge and skills related to cultural competency, cultural humility, and person-centered maternal care.

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Contraction Cycle” by Meredith Pomietlo is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “59ff6e63b50027fa0a5f7c1d7801ca7c85b33cc7” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/15-1-factors-influencing-the-process-of-labor-and-birth ↵

- “Station” by Meredith Pomietlo is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- “Fetal Heart Rate and Contraction Measurements by External Monitoring” by Meredith Pomietlo is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “5eb1b639302e984fa9c1b290a77d3c729ef4c5d9” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/15-1-factors-influencing-the-process-of-labor-and-birth ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “acd80ded2b51922805a2451e2f1612e676f83dfe” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/15-1-factors-influencing-the-process-of-labor-and-birth ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “08a45553e4699a61a1187382200ea14f6424207d” by Rice University/Open Stax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/11-4-care-in-the-third-trimester-of-pregnancy ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “6f144821339fc2a5864a72340c7f7294519a842c” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/15-1-factors-influencing-the-process-of-labor-and-birth ↵

- Makajeva, J., & Ashraf, M. (2023). Delivery, face and brow presentation. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567727/ ↵

- “d5c7477484ce99e656f9031a2d219eb05f61bdb5” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/15-1-factors-influencing-the-process-of-labor-and-birth ↵

- “78fe69c7c7a17a58f174da2683af2bae4d29df6b” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/15-1-factors-influencing-the-process-of-labor-and-birth ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Makajeva, J., & Ashraf, M. (2023). Delivery, face and brow presentation. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567727/ ↵

- Makajeva, J., & Ashraf, M. (2023). Delivery, face and brow presentation. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567727/ ↵

- Makajeva, J., & Ashraf, M. (2023). Delivery, pace and brow presentation. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567727/ ↵

- Makajeva, J., & Ashraf, M. (2023). Delivery, face and brow presentation. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567727/ ↵

- Makajeva, J., & Ashraf, M. (2023). Delivery, face and brow presentation. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567727/ ↵

- Makajeva, J., & Ashraf, M. (2023). Delivery, face and brow presentation. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK567727/ ↵

- “7bf31a4b3c1ee78142865fe61607daea17430890” by Rice University/Open Stax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/15-1-factors-influencing-the-process-of-labor-and-birth ↵

- “ROA” by Meredith Pomietlo is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- “ROP” by Meredith Pomietlo is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0 ↵

- Geeky Medics. (2018, September 14). Types of fetal positions - OSCE guide | UKMLA | CPSA [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-CLxiLOXdH4 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Office of Minority Health. (n.d.). Culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS) in maternal health care. Think Cultural Health. https://thinkculturalhealth.hhs.gov/education/maternal-health-care ↵

Essential factors that influence the process of labor and delivery including Power, Passageway, Passenger, Positioning, and Psych.

Refers to the strength of the uterine contractions that move the fetus through the pelvis during labor, as well as the maternal pushing efforts during delivery of the fetus.

A pattern of rhythmic tightening and relaxation of smooth muscle fibers of the uterus that cause downward pressure on the fetus.

An acronym used to assess uterine contractions and refers to Duration, Intensity and Frequency.

Refers to the time from the beginning to the end of one contraction.

Refers to the strength or force of uterine contractions during labor including classifications of mild, moderate, and strong.

The buildup of the contraction.

Refers to the peak of a contraction.

The gradual lessening of the contraction.

The time from the start of one contraction to the start of the next contraction.

Refers to the time of uterine relaxation between contractions.

Have enough duration, strength, and frequency to cause the cervix to dilate and efface and move the fetus through the maternal pelvis.

Patterns which do not cause cervical dilation, effacement, or fetal descent.

Insufficient uterine contractions.

The gradual thinning and shortening of the cervix and is measured from 0 percent to 100 percent.

The gradual opening of the cervix, measured in centimeters (cm), from 0 to 10 cm.

Refers to the level of the fetal presenting part in relation to the maternal ischial spines.

The widest part of the fetal presenting part has passed through the pelvic inlet and is at the level of the maternal ischial spines.

The uppermost part of the uterus.

Anon-invasive method used during labor to continuously monitor the well-being of the fetus and the progress of uterine contractions.

Pressure sensitive device.

An invasive method used during labor to continuously and accurately monitor the fetus's heart rate and uterine contractions.

The maternal pelvic structures and soft tissues.

One of the hormones that prepares the woman’s body for birth, softens the ligaments of the pelvis which then causes a shift in the pelvic floor anatomy to accommodate the changes in diameter needed for birth.

A circular inlet that is considered most favorable for vaginal delivery.

A long oval inlet and are associated with occipital posterior deliveries.

A short oval inlet.

A heart-shaped inlet that were historically thought to be associated with arrest of labor deep in the pelvis.

Third aspect of labor is the fetus.

Compression of these cranial bones, sutures, and fontanelles during labor and delivery.

Relationship of the fetal spine to the mother’s spine.

Refers to the fetal spine lining up vertically with the mother’s spine with the fetal head down in the maternal pelvis.

The position of the fetus in the womb where the head is positioned to be delivered first during childbirth.

The fetal spine is not lined up vertically with the mother’s spine and includes oblique lie and transverse lie.

The fetal spine lines up diagonally with the mother’s spine.

The fetal spine is horizontal to the mother’s spine, similar to a plus (+) sign.

The fetal part present in the lower part of the uterus.

The fetal part present in the lower part of the uterus.

Position in which the fetal buttocks (or legs) enter the pelvis first.

Presentation in which the fetus is in a transverse lie and the shoulder enters the pelvis first.

The most common type cephalic presentation, meaning the fetal head is down in the maternal pelvis with its neck flexed and the chin tucked into its chest, thus minimizing the diameter of the fetal head to conform to the maternal pelvis.

Refers to the presence of extension of the fetal head and neck.

The neck is slightly flexed, and the forehead is the presenting part of the fetal head.

Presentation in which the neck is fully extended.

Protruding part of the chin.

Breech position in which the fetus presents bottom first with legs straight up toward head.

Breech presentation in which the fetus presents bottom first with legs crossed.

Breech position in which the fetus presents one leg first.

Refers to the relationship of the presenting fetal part to the mother’s pelvic anatomic landmarks.

Position in which the back of the skull (near the occipital bone) is the leading presenting fetal part.

Position in which the fetal occiput is close to the maternal symphysis pubis, and the face is pointed towards the mother’s spine.

Position in which the occiput slightly facing the mother’s left side.

Position in which the occiput slightly facing the mother’s right side.

Positions mean the fetal occiput is close to the maternal spine, and the face is pointed toward the maternal symphysis pubis.

Position in which the back of the fetal head slightly faces left.

Position in which the back of the fetal head slightly faces right.

Position in which the fetal head is down and the chin is tucked but the head is lying sideways in the birth canal.

Means the fetal chin is facing the mother's abdomen.

Position in which the fetal chin is facing the mother's abdomen slightly to the right.

Position in which the fetal chin is facing the mother's abdomen slightly to the left.

Means the fetal chin is facing the mother’s spine.

The fetal chin is facing the mother’s spine, to the right.

Position in which the fetal chin is facing the mother’s spine, slightly to the left.

The fetal head is down with the chin facing the spine, but the face is lying sideways in the birth canal.

Frequent movement changes by the mother promote normal physiological progression of labor and fetal descent through the pelvis.

Refers to the psychological emotional state of the mother giving birth and plays an important role during labor and delivery.