10.10 Applying the Nursing Process and Clinical Judgment Model to Labor and Delivery Care

This section applies the nursing process to caring for a client in labor. Steps of the NCSBN Clinical Judgment Measurement Model are listed in parenthesis next to each step of the nursing process.

Assessment (Recognize Cues)

Obstetric Triage

When a pregnant woman arrives at a birthing unit, clinic, emergency department, or other health care agency in possible labor, the nurse performs an obstetric triage assessment. Sometimes, early labor can be challenging to distinguish from false labor. The nurse uses clinical judgment and criteria described in Table 10.10a to assess if a client is in true labor and ready to be admitted for active labor management and delivery.[1]

Table 10.10a. Assessment Findings During True Labor Versus Braxton-Hicks Contractions[2],[3]

| Assessment | Findings |

|---|---|

| Contraction Characteristics |

|

| Cervical Examination | A cervical examination is performed to assess the dilation (opening) and effacement (thinning) of the cervix. In true labor, the cervix typically starts to dilate and efface. |

| Assessment of Progression | Nurses observe for signs of progression of labor over time. True labor involves a progressive change in contractions, cervical dilation, and effacement. |

| Rupture of Membranes | The presence of amniotic fluid in or leaking from the vagina can be confirmed through visual inspection or testing. The amniotic sac may rupture spontaneously during true labor. |

| Bloody Show | A small amount of bloody discharge or mucus plug is often expelled as the cervix begins to dilate during true labor. |

| Client’s Pain and Perception | The client’s description of pain and discomfort provides valuable subjective information. Braxton-Hicks contractions are often only felt in the front of the abdomen or in one specific area. True labor contractions often start in the midback and wrap around the abdomen towards the midline. True labor contractions continue despite movement, position change, or rest, whereas Braxton-Hicks contractions may stop with a change in position, a change in the level of activity, or rest. For example, if a client can sleep through the contractions, it is a Braxton-Hicks contraction. |

| Assessment of Other Signs | Nurses assess for other signs of imminent delivery, such as the urge to push, pressure in the lower back or pelvis, a bowel movement, or crowning of the fetal head. Signs of imminent delivery require immediate medical assistance. |

Assessment data is shared with the health care provider and a decision is made regarding admission to a labor and delivery unit. If assessment data indicates the client is experiencing Braxton-Hicks contractions and not true labor, the nurse teaches the client actions to ease the discomfort of contractions such as the following[4]:

- Change position or activity level: If the client has been very active, lie down and rest. If the client has been sitting for an extended time, go for a walk.

- Use relaxation techniques: Take a warm bath, get a massage, read a book, listen to music, or take a nap.

- Hydrate: Drink water to rehydrate.

However, if these actions do not lessen the Braxton-Hicks contractions or if the contractions continue and become more frequent or more intense, the nurse advises the client to contact the health care provider. Furthermore, if any of the following signs are present, the nurse should contact the health care provider immediately[5]:

- Vaginal bleeding

- Leakage of fluid from the vagina

- Strong contractions every five minutes for an hour

- Contractions that the client is unable to “walk through”

- A noticeable change in fetal movement, or if there are fewer than ten fetal movements every two hours

Admission Assessments

When a client is admitted to the birthing unit, the nurse creates a welcoming environment and establishes a caring, nonjudgmental, therapeutic relationship with the client, partner, support person, and/or birthing family. The nurse is aware there are many different emotions the client, partner, and birthing family may be experiencing, including anxiety, fear, and excitement. The nurse is also aware of variations in individuals’ birthing preferences and expectations and assesses the needs and cultural birthing practices of the client, partner, and/or birthing family. For example, clients from some cultures prefer to avoid moving too much during labor or to lie down, sit, or squat. Others incorporate rituals and ceremonies into labor and birth, such as smudging (burning sacred herbs to cleanse, purify, and connect with the spirit world), drumming, singing, and bathing.[6]

Initial admission assessments include obtaining maternal vital signs and initiating fetal heart rate monitoring to ensure fetal well-being. The client’s prenatal record is reviewed by the nurse, including obstetric history, surgical history, medical history, and laboratory and diagnostic test results. The nurse also obtains a health history and performs a physical exam, including a sterile-gloved vaginal exam to determine the degree of cervical dilation and effacement. During the cervical exam, the presenting fetal part and fetal position are also determined. Bedside ultrasound may be performed to confirm the presentation and position of the fetal presenting part. The health care provider is notified of a breech presentation due to its increased risks regarding fetal morbidity and mortality compared with a cephalic presentation.[7]

Review of the Prenatal Record

Laboratory and Diagnostic Testing

The prenatal record is an excellent source of information when a client presents to the labor and delivery unit. In reviewing the prenatal history, the nurse notes preexisting conditions that may impact the care of the laboring person and fetus. Baseline prenatal laboratory tests are reviewed, including complete blood cell count (or hemoglobin and hematocrit); blood type, Rh factor, and antibody screen; rubella titers; hepatitis B and C; human immunodeficiency virus (HIV); and sexually transmitted infection (STI) screening. Subsequent lab results are monitored to identify trends or changes throughout labor. Abnormal findings require notification of the health care provider. Pertinent diagnostic tests, including ultrasound results, are reviewed for fetal presentation, positioning, or abnormalities. The estimated due date and any fetal testing are noted.[8]

Review prenatal labs in the “First Prenatal Visit,” “First Trimester Prenatal Care,” “Second Trimester Prenatal Care,” and “Third Trimester Prenatal Care” sections of the “Antepartum Care” chapter.

Genetic History

The nurse reviews the genetic history of the laboring client and other biological parent from the prenatal record or obtains information directly from the client if prenatal records are not available. Prenatal genetic screening and diagnostic tests help identify and manage potential risks and enable timely interventions as indicated. For example, genetic disorders that affect blood clotting or bleeding increase the risk of morbidity and mortality during labor and should be addressed during the initial admission intake. The medical team is notified of a family history that includes birth defects, newborn screening disorders, or any genetic disorders that could affect the care of the laboring person or fetus such as the following[9]:

- Down Syndrome (Trisomy 21): Down syndrome is a chromosomal disorder caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21 that can cause physical abnormalities and intellectual disabilities of the newborn.

- Cystic Fibrosis: Cystic fibrosis is a genetic disorder that affects the respiratory and digestive systems.

- Sickle Cell Trait or Sickle Cell Disease: Prenatal genetic testing can determine if both parents carry the sickle cell trait, increasing the risk of having a newborn with sickle cell trait or sickle cell disease. Sickle cell disease is more common in people of African, Mediterranean, and Middle Eastern descent and causes painful sickling episodes and anemia that affect oxygenation.

- Tay-Sachs Disease: Tay-Sachs is a rare genetic disorder that affects the nervous system and is more common in people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent.

- Hemophilia: Hemophilia impairs blood clotting. It primarily affects males, and carriers of the gene can pass it on to their children.

- Neural Tube Defects: Conditions like spina bifida and anencephaly are congenital neural tube defects that can have genetic components. Newborns with neural tube defects may require immediate care by the pediatric medical team.

- Congenital Heart Defects: Some congenital heart defects have a genetic basis. Congenital heart defects may immediately affect the newborn after delivery when fetal circulation transitions to newborn circulation.

Medical History and Medications

Medical history that may impact labor and delivery is reviewed and documented, including diabetes, hypertension, and thyroid disorder. Medications taken during pregnancy are documented, including the client report of the last time the medication was taken. Medication allergies are verified and documented.[10]

Obstetric and Gynecological History

The obstetric and gynecologic history is reviewed, including the number of prenatal care visits, the number of previous pregnancies, and the number and type of previous deliveries, and any complications. The last menstrual period (LMP), estimated date of delivery (EDD), and gestational age are reviewed and documented. History of previous conditions such as uterine fibroids or cervical cerclage (temporarily sewing the cervix closed to prevent preterm birth) that could impact the labor process are documented. If a laboring client has a history of a sexually transmitted infection (STI) during the current pregnancy, the nurse investigates whether treatment was initiated and completed, whether all sexual partners were concurrently treated, and whether the test of cure was completed with negative results. Any STI diagnosed during the pregnancy, its treatment, and verification of the effectiveness of the treatment are reported to the health care provider and the pediatric health care provider assigned to the care of the newborn.[11]

Psychosocial History

A psychosocial history related to social determinants of health and other conditions that can impact postpartum and newborn care is obtained, such as safe housing; available transportation; and access to phone, utilities, and appliances for cooking and cleaning. The availability of support persons, history of mental health conditions, preparation for labor and birth, knowledge about newborn care, and any history of intimate partner violence is also assessed and incorporated into the nursing care plan.[12]

Labor and birthing preferences are obtained, including the client’s preferences for pain management and any special considerations regarding cultural or religious beliefs. Cultural assessment questions can include the following[13]:

- Dietary preferences: Do you have any dietary preferences during your hospital stay related to your cultural or religious beliefs?

- Birth customs: Are there any special customs you would like to do during childbirth? What does a “good birth” mean to you?

- Pain management: How do you prefer to manage labor pain? Do you plan to use any specific rituals, treatments, or methods instead of or in addition to medications?

- Family dynamics: Who makes medical decisions for you and your family members?

- Language: In what language are you most comfortable speaking and reading? Would you like an interpreter?

General Survey

The nurse observes the laboring client’s appearance and behavior, as well as their dynamics with the partner or support person. Deviations from expected findings should be documented and additional interventions implemented.[14]

Review information regarding evaluating family dynamics in the “Family Dynamics” section of the “Family Dynamics” chapter.

Maternal and Fetal Physical Examination

The following assessments are performed on admission and throughout labor. Concerning findings should be reported promptly to the health care provider to ensure timely intervention and a safe delivery for both the mother and the baby.

- Vital signs: Baseline blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and temperature are assessed on admission and monitored hourly throughout labor or more frequently according to agency policy.

- Pain: A pain scale (such as the numeric rating scale) is used to consistently evaluate the intensity of labor pain and the effectiveness of pain relief measures. Use of coping strategies such as nonpharmacological techniques (e.g., breathing, positioning, etc.), analgesics, or anesthetics (e.g., epidural or spinal block) is documented throughout labor, as well as their effectiveness. Review pain assessment and interventions in the “Pain Management During Labor and Delivery” section.

- Heart, Lungs, and Extremities: Heart and lung sounds are auscultated, and the client is inspected for edema. Dependent edema of the extremities can be a normal finding related to increased fluid volume during pregnancy, but generalized edema of the face, hands, and feet is associated with preeclampsia. If the client has other signs of preeclampsia, such as headache, visual disturbances, increased deep tendon reflexes and/or clonus, the health care provider should be immediately notified.

- Uterine Contractions and Fetal Monitoring: The duration, intensity, and frequency of contractions are assessed on admission and then monitored intermittently or continuously during labor based on agency policy and provider orders. Fetal heart rate is monitored intermittently every 15–60 minutes or continuously during labor based on low- or high-risk labor status and agency policy. Review information about fetal monitoring in the “Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring” section.

- Amniotic membrane status: The nurse notes if the amniotic membranes have ruptured before arrival. If they rupture spontaneously during labor, the time is noted, as well as the characteristics of the amniotic fluid, including color, odor, and amount. Amniotic fluid is expected to be clear; abnormal findings of green or yellow color are associated with meconium-stained fluid, and bloody fluid is associated with placenta previa or abruption. Assessment for signs of rupture of membranes may include pH testing, microscopic exam looking for ferning of the fluid, or laboratory testing of the fluid. Amniotic fluid has a pH of 7.0 to 7.5, which is more basic than normal vaginal pH.

- Abdominal examination: Leopold’s maneuvers are performed to determine fetal lie.

- Vaginal examination: Vaginal examinations are performed with sterile gloves on admission and throughout labor to assess for cervical dilation and effacement, as well as descent of the fetal presenting part through the maternal pelvis. The measurement of cervical dilation is made by locating the external cervical os and spreading one’s fingers in a ‘V’ shape and estimating the distance in centimeters between the two fingers. Effacement is measured by estimating the percentage remaining of the length of the thinned cervix compared to the uneffaced cervix. During the cervical exam, the presenting fetal part and fetal position are also determined. Bedside ultrasound may be performed to confirm the presentation and position of the fetal presenting part. The nurse notes fetal lie (e.g., longitudinal, oblique, or transverse), fetal presentation (e.g., vertex/cephalic or breech), position of the presenting part (e.g., occiput, mentum, or sacrum is anterior, posterior, or transverse), and station of the fetal presenting part (-5 cm to 5+ cm). A vaginal exam is deferred in the case of vaginal bleeding, documented placenta previa, or other factors where a vaginal examination may result in complications. Bloody show is a normal finding during labor, but the presence of bright red or dark red bleeding or trickling of blood is abnormal and requires urgent notification of the health care provider.[15],[16]

- Labor progress: Labor progress is monitored based on the uterine contraction pattern, changes in cervical dilation and effacement, fetal station indicated based on the client’s presentation, significant changes in client behavior, or the feeling of pressure and the urge to push.

- Perineum: The perineum is assessed for swelling, bruising, or signs of imminent delivery (e.g., crowning).

- Urinary output: Urine output is monitored to ensure adequate hydration and kidney function.

- Emotional status: The emotional well-being of the client and their partner are monitored throughout labor, and emotional support is provided. The nurse continuously communicates, provides encouragement, and answers questions or concerns.

- Signs of maternal or fetal distress: The nurse is vigilant for signs of abnormalities or complications during labor. The health care provider is immediately notified about findings such as abnormal fetal heart rate or uterine contractions, umbilical cord prolapse, or vaginal bleeding.

Performing a Sterile Vaginal Exam

- Explain the procedure to the client and obtain consent using a trauma-informed approach.

- Drape a sheet over the client’s pelvic area to maintain privacy during the exam.

- Don a sterile glove on your dominant hand and then lubricate the index and middle fingers.

- Inform the client you will be inserting two fingers into the vagina, and they will feel pressure.

- After inserting your fingers into the vagina, locate the cervix. Assess the cervix for the following:

- Cervical Dilation: Estimate the distance between one side of the cervix and the other and document dilation in centimeters

- Cervical effacement: Estimate the length of the cervix. A cervix is 0 percent effaced when it is 2 cm long and 100 percent effaced when it is paper thin. Estimate the percentage between 2 cm and paper thin.

- Cervical position: A cervix that “points” toward the client’s back is in a posterior position, whereas an anterior position is oriented toward the vaginal introitus. If the cervix is located somewhere between the two, it is in the midposition.

- Assess fetal presentation as cephalic (vertex) or breech.

- Assess fetal station: Determine the level of the fetal presenting part in relation to the ischial spines of the maternal pelvis.

- Assess fetal position: Palpate the relationship of the presenting fetal part (occiput, mentum, sacrum, etc.) in relation to the maternal pelvis (anterior, posterior, or transverse).

Note: Frequent vaginal examinations can introduce bacteria into the birth canal, potentially increasing the risk of infection and causing conditions like urinary tract infections or chorioamnionitis (infection of the fetal membranes). Frequent or aggressive cervical checks can also cause cervical edema and bleeding, potentially leading to cervical injury or hematoma formation. Follow agency policy and use clinical judgment regarding the frequency of vaginal examinations.

View a supplementary YouTube video[17] on performing abdominal examination on a pregnant woman: Pregnant Abdomen Examination (a.k.a. Obstetric Abdominal Examination) – OSCE Guide | UKMLA | CPSA.

Diagnosis (Analyze Cues)

During initial and ongoing assessment of the client during labor and delivery, relevant cues are recognized and analyzed, and nursing problems (diagnoses) are identified. Several nursing diagnoses may apply to clients during labor and delivery, such as the following[18]:

- Labor Pain related to uterine contractions

- Knowledge Deficit related to pain management

- Anxiety related to labor and birth

- Fatigue related to prolonged labor

- Risk for Ineffective Coping related to inadequate sense of control

- Risk for Infection due to prolonged rupture of membranes

- Decreased Cardiac Output related to supine hypotension secondary to maternal position

- Risk for Unstable Blood Glucose due to gestational diabetes

- Risk for Deficient Fluid Volume due to lack of fluid intake during labor

- Risk for Impaired Skin Integrity due to large for gestational age fetus

- Risk for Interrupted Family Processes due to developmental transition

- Risk for Injury (fetal) related to hypoxia

- Impaired Gas Exchange (fetal) related to cord compression

Outcome Identification (Generate Solutions)

Outcome criteria are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, time-oriented, and based on the specific client circumstances and applicable nursing diagnoses. Sample SMART goals related to labor and delivery are as follows[19]:

- The client will effectively use breathing and relaxation techniques to manage anxiety after the teaching session.

- The client will use effective techniques to conserve energy between contractions throughout labor and delivery.

- The fetus will display FHR and beat-to-beat variability within normal limits, with no ominous periodic changes in response to uterine contractions during labor and delivery.

- The client and partner will demonstrate behaviors indicating readiness to actively participate in the acquaintance process when mother and newborn are physically stable after delivery.

Implementation (Take Action)

The nurse plays an important role in supporting a pregnant woman and their partner or support person during labor and birth. See Figure 10.68[20] for an image of a nurse assisting during delivery of a newborn. Nursing interventions will be discussed in this subsection based on the three stages of labor.

Nursing Interventions During the First Stage of Labor

During the first stage of labor, the nurse provides emotional support and teaches the client and their partner about the importance of position changes and movement to promote labor progress, promotes breathing and nonpharmacological techniques to manage pain, and administers and/or evaluates pharmacological pain relief measures. The nurse regularly monitors fetal heart rate and uterine contractions and monitors labor progress while assessing for potential complications. If abnormal findings occur, the nurse promptly notifies the health care provider. If an amniotomy is performed for labor augmentation, the nurse assists the health care provider during this procedure. The nurse also provides health teaching applicable to the first stage of labor.

Providing Emotional Support

The onset of labor can be a time of excitement and anxiety for new parents. The nurse can provide emotional support to the laboring person and partner by answering questions that they may have. The nurse can ease the laboring person’s anxiety by explaining the expected progression of labor and creating a plan of care with the laboring person and the partner. The nurse should ask the laboring person how they envision their labor and how their wishes can be accommodated while discussing any potential barriers to their desired birth plan. Throughout the labor and delivery, the nurse should discuss any changes with the laboring person and their partner and continually explain what is happening.

Encouraging Position Changes and Movement

The nurse encourages the client to change positions and ambulate during the first stage of labor. The nurse provides health teaching about the benefits of position change and ambulation and demonstrates how the partner can assist during the labor process. The laboring person should be advised that lying flat on their back can result in hypotension related to the compression of the vena cava. Walking and upright positions have been shown to decrease the duration of the first stage of labor. Compared to supine or semi-Fowler’s positions, upright positions during labor often result in shorter labors, fewer interventions, and decreased pain for laboring persons. In addition, upright positions allow gravity to assist in bringing the fetus down. No matter the position, frequent position changes create slight movement in the pelvic bones and help the fetus find the best fit into the pelvis.[21] Table 10.10b summarizes recommendations for maternal positions to change fetal position during labor.

Table 10.10b. Position Changes to Change Fetal Positions During Labor[22]

| Goal | Recommended Maternal Positions |

|---|---|

| Changing Fetal Position During Labor | Position changes to facilitate labor progress:

|

| Changing Fetal Station During Labor | When the fetal head is high in the pelvis (above 0 station), position changes can help engage the head in the pelvis and encourage descent:

If the fetal head is low in the pelvis (below 0 station) but not progressing, these position changes can help facilitate descent:

|

Every labor is unique, and the effectiveness of position changes varies from person to person. Providing continuous communication with the client and their partner or support person, monitoring the fetal heart rate, and working collaboratively with the health care provider are essential for promoting safe and effective labor progress.[23]

Review position changes and movement in the “Nonpharmacological Interventions” subsection in the “Pain Management During Labor and Delivery” section.

Encouraging Breathing Techniques and Nonpharmacological Pain Management

Breathing and relaxation techniques can assist with pain management, decrease anxiety, relax pelvic muscles to allow descent of the fetus, and maintain blood oxygen levels for the client and fetus.

Review breathing and other nonpharmacological pain management techniques in the “Nonpharmacological Interventions” subsection in the “Pain Management During Labor and Delivery” section.

Providing Pharmacological Pain Relief

Pain management is based on the client’s preferences. The nurse plays an integral role in implementing the client’s pain management plan. Some clients prefer nonpharmacologic pain management strategies, and others prefer analgesics or epidural anesthesia. When a client desires analgesia, the nurse teaches about prescribed pain medications and side effects, administers medication, and evaluates for effectiveness. If a client requests epidural anesthesia, the nurse assists in obtaining written informed consent, positions the client prior to the procedure, and monitors the client and fetus during administration of epidural medication.

Review information about analgesia and anesthesia in the “Pharmacological Interventions During Labor and Delivery” subsection in the “Pain Management During Labor and Delivery” section.

Monitoring Fetal Heart Rate, Uterine Contractions, and Potential Complications

Fetal heart rate monitoring during the first stage of labor is based on agency policy and provider orders. The Association of Women’s Health, Obstetric and Neonatal Nurses (AWHONN) recommends electronic monitoring of fetal heart rate and uterine contractions during uncomplicated pregnancies be reviewed every 15 to 30 minutes during the first stage of labor. When intermittent auscultation is used, fetal monitoring during the early phase of labor is at the recommendation of the health care provider and every 15 to 30 minutes in the active and transition phases. If clients present with or develop complications during labor, the recommendation is to review fetal heart rate monitoring every 15 minutes or continuously during the first stage of labor, allowing for prompt intrauterine resuscitation or delivery.[24]

Review the “Fetal Heart Rate Monitoring” section for information on fetal heart rate and uterine activity monitoring.

During the first stage of labor, the most common complications are related to abnormal fetal heart rate changes and labor progress that deviate from normal.

Review the “Complications Associated With Labor” section for additional information about complications that can occur during the first stage of labor.

Monitoring Labor Progress

Nurses perform cervical examinations at appropriate intervals to assess labor progress based on agency policy and provider orders. However, unnecessary or too frequent cervical checks should be avoided because they can increase the risk of infection. The nurse monitors cervical dilation, cervical effacement, fetal presentation, fetal station, and fetal position.

Review information about labor dystocia in the “Dystocia” subsection of the “Complications Associated With Labor” section.

Assisting With Amniotomy

The nurse may assist the health care provider during an amniotomy, commonly known as artificial rupture of membranes (AROM), to promote labor progress.

Review information about an amniotomy in the “Dystocia” subsection of the “Complications Associated With Labor” section.

Providing Health Teaching During the First Stage of Labor

The nurse is a continual resource for educating the laboring client about what to expect, what is occurring, and options they can consider during labor. The client and their partner or support person are encouraged to ask questions and clarify information presented by the nurse or health care team.[25]

Upon admission, the nurse reviews the process of labor and birth and what to expect. The client and their partner should understand the first stage of labor begins with early dilation and ends at full dilation and effacement and then pushing will begin. The nurse teaches about pain management options and the value of position changes, movement, and rest between contractions, as well as the importance of keeping hydrated during labor.[26]

When applying external fetal monitoring equipment or auscultating fetal heart rate, the nurse teaches the client and their partner or support person on the importance and reason for fetal monitoring during labor. A brief description of what the health care team is monitoring and that the monitoring is continually being watched, even when staff are not present in the room, can reassure the client and their partner and help decrease anxiety.[27]

Nursing Interventions During the Second Stage of Labor

The second stage of labor begins when the cervix is completely dilated and 100% effaced and then maternal pushing efforts can begin. The average nulliparous client without an epidural will need to push effectively for two to three hours to birth their newborn. With an epidural, the expected time frame expands to three to four hours. For an average multiparous person, the second stage lasts up to an hour or expands to two hours with an epidural.[28]

Perineal bulging with maternal efforts, visualization of the fetal presenting part, and passing of maternal stools are signs that progress is being made. If progress is unclear within the first 30 minutes of the second stage of labor, the nurse should promote position change and directing the maternal pushing effort down toward the rectum or changing between open-glottis and closed-glottis pushing to find what works for the birthing person. Research has shown benefits for changing positions during the second stage, with upright or side-lying positions showing improved outcomes for the birthing person and fetus and lithotomy or supine positions causing increased risk for perineal tearing, longer pushing time, more pain, and increased fetal heart rate abnormalities. The nurse may also assist in providing perineal massage during the second stage of labor to prevent episiotomy and decrease the duration of pushing. Research shows that nurses who are educated on optimal position changes and pushing techniques reduce cesarean rates compared to those who do not complete this additional education.[29]

The nurse typically remains at the bedside when the client is pushing during the second stage of labor. In addition to continuing to monitor fetal heart rate, fetal descent, and uterine contraction patterns, the nursing encourages bearing down efforts, promotes comfort and encourages position changes, monitors for complications, and prepares for birth.

Encouraging Pushing Efforts

The direct contact of the fetal head on the pelvic floor usually initiates the maternal urge to push. However, this sensation may be dulled if an epidural is in place. The role of the nurse is to provide motivation and encouragement for effective pushing efforts. Controlled, slow, and supported pushing during contractions helps avoid rapid fetal descent. The nurse will coach the client to coordinate their pushing and breathing efforts with uterine contractions and will provide feedback to the birthing person about their pushing efforts. The nurse also maintains communication with the health care provider about the pushing progress as the fetus goes through the cardinal movements and crowns.[30]

During open glottis pushing, the client follows their body’s spontaneous, natural urges to push while breathing naturally. They take deep breaths in and exhale naturally as they feel the urge to bear down and push. During closed glottis pushing, the client is instructed to hold their breath and push forcefully for a specified duration during each contraction. Studies suggest that there is no difference in the incidence of perineal lacerations between open and closed glottis pushing.[31]

Encouraging Position Changes

Changing positions during labor can be highly beneficial in promoting the descent of the fetus through the birth canal. Different positions can help optimize the alignment of the fetal head with the pelvis, facilitate uterine contractions, and reduce pressure on specific areas, potentially making the labor process more efficient and comfortable.

When the fetal head is crowning, position changes focus on guiding the head through the birth canal, such as squatting during contractions (using a squat bar if available), using supported or unassisted upright positions, or kneeling or hands and knees. The choice of position should be based on client comfort and what feels most effective during labor.[32]

Review the “Position Changes and Movement” subsection of the “Nonpharmacological Interventions” subsection of the “Pain Management During Labor and Delivery” section.

Promoting Relaxation and Comfort Measures During the Second Stage of Labor

Promoting relaxation and comfort during the second stage of labor varies based on the client’s pain management preferences. For a client who has an epidural, the nurse can assist with repositioning and creating a calm, quiet environment. For a client using analgesics or nonpharmacologic methods, the nurse can also encourage breathing techniques and additional comfort measures like warm compresses applied to the perineum or lower back, cool washcloths to the forehead or neck, or applying pressure or massage to the lower back.[33]

Monitoring for Complications During the Second Stage of Labor

The second stage of labor brings about the potential for additional complications that may affect the client or the fetus. The nurse continually assesses for complications, including prolonged second stage, fetal distress, shoulder dystocia, and rapid delivery as outlined in Table 10.10c. The second stage of labor is a time of increased stress on the fetus, and the nurse must continuously monitor the fetal heart rate to ensure the safe delivery of the newborn. Communication with a health care provider who is not at the bedside should continue consistently throughout the second stage of labor. Any changes in maternal or fetal status should be reported immediately to the health care provider. The nurse must also monitor for shoulder dystocia and be prepared to react and assist the health care provider in repositioning maneuvers or performing emergency cesarean birth to deliver the newborn.[34]

Table 10.10c. Nursing Assessments and Actions for Complications During the Second Stage of Labor

| Complication | Nursing Assessment |

|---|---|

| Prolonged Second Stage |

|

| Fetal Distress |

|

| Shoulder Dystocia |

|

| Rapid Delivery |

|

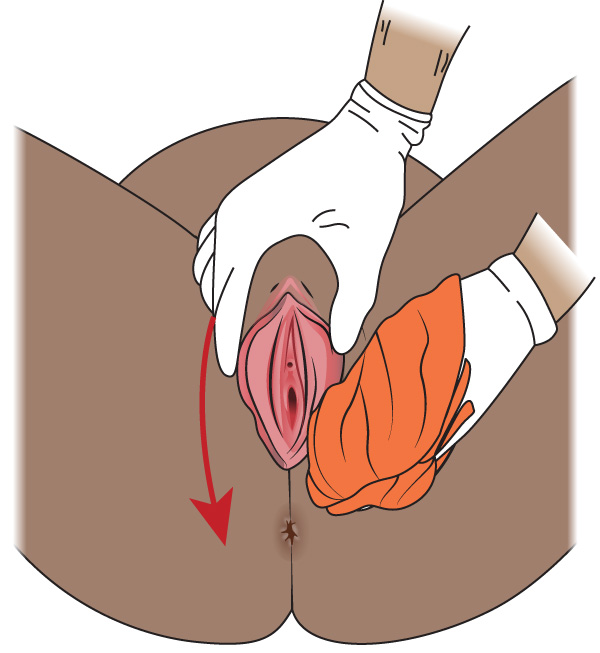

Providing Perineal Hygiene

Perineal hygiene is recommended during the second stage to decrease the risk of infection. The nurse should be aware of agency policy regarding perineal cleansing and assist the health care provider as indicated. Perineal hygiene may include pouring warm water over the perineum or using wet washcloths to cleanse the perineum moving from the pubic hair line to the anus using a front-to-back motion. A separate area of the washcloth should be used for each stroke to prevent contamination from the rectum to the vaginal area. After cleansing, a clean washcloth is used to remove soap or antiseptic solution from the perineum using a front-to-back motion.[35] See Figure 10.69[36] for an illustration of perineal hygiene.

Preparing for Birth

During the second stage of labor, the nurse begins to prepare for the birth of the newborn by ensuring a delivery table and infant warmer are in the room and ready for use.

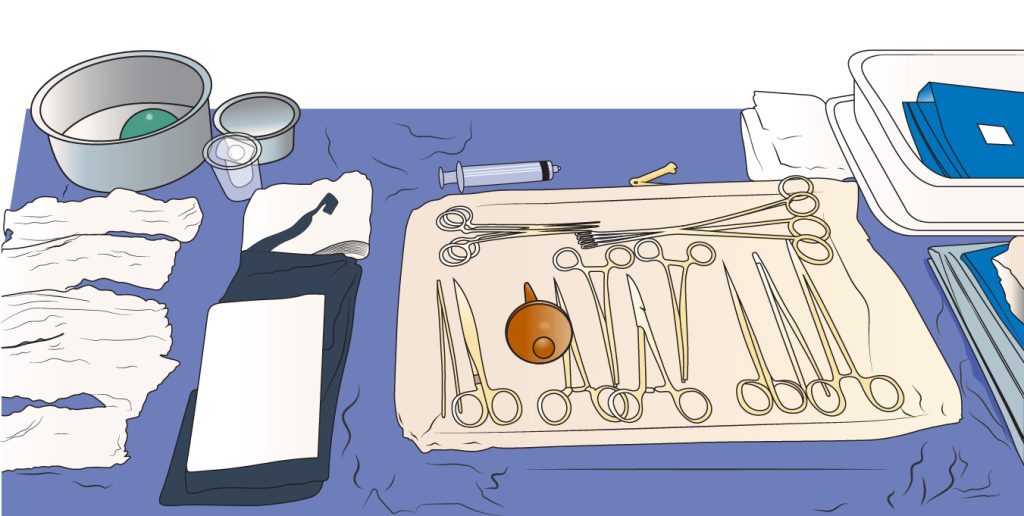

Delivery Table

A delivery table is typically set up that contains sterile drapes, bulb syringe, cord clamp, sponges, syringe for local anesthesia, delivery equipment, and instruments to complete repairs to the perineum if necessary. The contents of the delivery table vary based on agency policy and provider preferences. See Figure 10.70[37] for an illustration of a delivery table setup.

Infant Warmer

An infant warmer is also set up in the room that allows for rapid resuscitation of the neonate if necessary. The warmer should be stocked and its contents verified by the nurse before delivery. See Table 10.10d for a list of common equipment and supplies in the warmer. The warmer should be turned on by the nurse before delivery, allowing enough time for the warmer to preheat to the desired temperature. The labor nurse should also make sure oxygen and suction are set up and working. See Figure 10.71[38] for an image of an infant warmer.[39]

Table 10.10d. Equipment in the Infant Warmer[40]

| Type | Equipment |

|---|---|

| Resuscitation Equipment |

|

| Oxygen Equipment |

|

| Thermoregulation |

|

| Monitoring and Assessment |

|

| Umbilical Cord Care |

|

| Suction and Oral Care |

|

| Miscellaneous |

|

Collaborating With the Interprofessional Health Care Team

Delivery of the newborn may include collaboration of multiple health care providers, which can feel overwhelming to the client and their partner. The nurse explains the role of each member of the team and their purpose. In addition to the primary nurse assigned to the laboring client and the health care provider, an additional nurse attends the delivery to support the newborn, complete a newborn assessment, and initiate resuscitation with the neonatal resuscitation team if warranted. A respiratory therapist and pediatrician may also be present, as indicated and based on agency policy. The nurse also communicates with the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) to coordinate and prepare for delivery or resuscitation as indicated.[41]

Providing Health Teaching During the Second Stage of Labor

During the second stage of labor, the nurse explains what occurs during the pushing stage and involves the partner in active participation and support of the client. The nurse teaches about the purpose of position changes and relaxation strategies and explains the purpose of the delivery table and infant warmer.

Nursing Interventions During the Third Stage of Labor

Nursing care during the third stage of labor focuses on monitoring the mother’s vital signs and pain, administering uterotonic medication, assessing the uterus and lochia, performing a newborn assessment, and promoting parent-newborn bonding. During this time, the nurse may also assist the health care provider with perineal repairs while caring for the mother and newborn.[42]

Monitoring the Maternal Response During the Third Stage of Labor

The nurse assesses the client’s vital signs, including blood pressure, pulse, respiratory rate, and pain while awaiting the delivery of the placenta. The uterus continues to contract following the birth of the newborn, which may cause mild to moderate pain requiring the administration of analgesics. The nurse may guide the client in bearing down to deliver the placenta. After the placenta is delivered, the nurse assesses the vaginal bleeding for amount, color, and clots, as well as the uterus for firmness, location, and tone.[43]

Administering Uterotonics

Active management of the third stage of labor is aimed at preventing postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). Medications called uterotonics increase the tone and contractility of the uterus and are administered immediately following the birth of the newborn or delivery of the placenta. Oxytocin is typically the first-line uterotonic administered intravenously or intramuscularly to reduce maternal blood loss. If additional uterotonics are required to treat PPH, prescribed medications may include misoprostol, methylergonovine, carboprost, or tranexamic acid.[44]

Monitoring for Signs of Separation of the Placenta

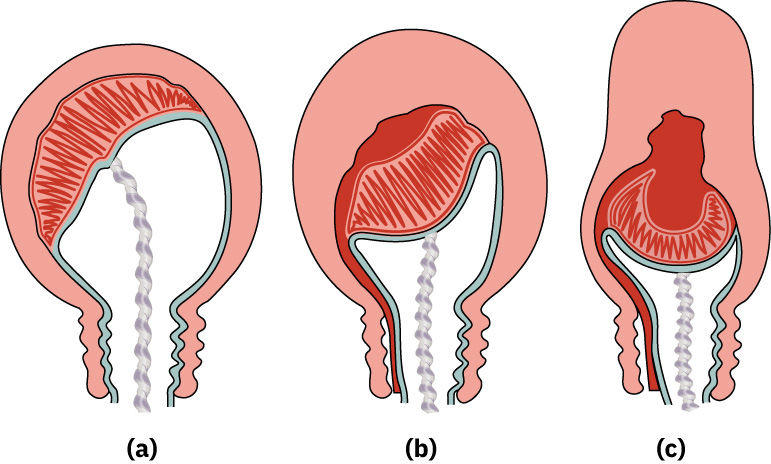

The reduction in uterine size, uterine contractions, and cord traction contribute to the separation of the placenta from the uterine wall. See Figure 10.72[45] for an illustration of separation of the placenta. Separation of the placenta from the uterus results in the following three hallmark signs[46]:

- The shape of the uterus changes to a spherical or round shape.

- A gush of blood from behind the placenta appears in the vagina.

- The umbilical cord lengthens as the placenta detaches and moves into the introitus.

Spontaneous delivery of the placenta occurs following the separation from the uterus. If the placenta is not delivered spontaneously, the health care provider may manually extract the placenta from the uterine wall, but manual extraction increases the risk of infection and postpartum hemorrhage (PPH). Following spontaneous or manual expulsion of the placenta, the health care provider inspects that the placenta is intact. Any piece of the placenta that remains inside the uterus or attached to the uterine wall interferes with the effective contraction of the uterus and increases the risk of PPH.[47]

Perineal Cleansing

After the delivery of the placenta, the health care provider may perform perineal cleansing to view the vagina and perineum for lacerations. Nursing actions include providing the health care provider with sponges and cleansing solutions as indicated. During this time, the health care team will count the used blades and needles, sponges, and vaginal packing, if used, to ensure that no foreign bodies are retained inside the uterus.[48]

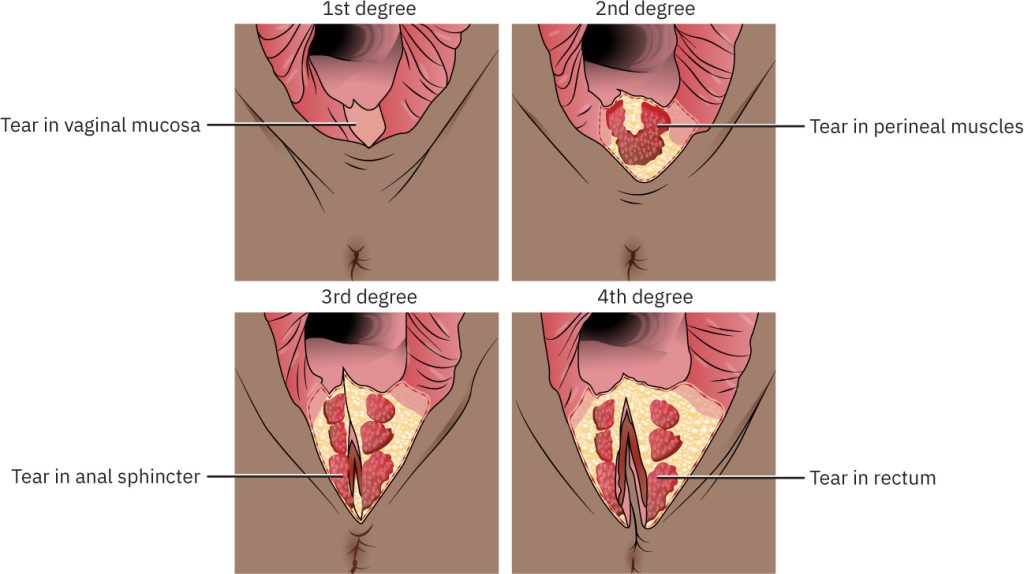

Lacerations

Soft tissue trauma during the third stage of labor is common and can vary in severity. It is not uncommon for a birthing person to experience edema or ecchymosis of the soft tissue. Some birthing persons may experience significant lacerations to the cervical, vaginal, and perineal tissues that require repair. Perineal and vaginal lacerations are classified as first, second, third, or fourth degree. See Figure 10.73[49] for illustration of lacerations. A first-degree laceration of the labia and perineum affects the skin and subcutaneous tissue. A second-degree laceration affects the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle of the perineum, as well as the vagina. When a perineal tear extends to or through the anal sphincter, this designates a third-degree laceration. A fourth-degree laceration includes damage to the pelvic floor and surrounding anal and rectal mucosa. Nurses may assist during laceration repair by providing specific suture needles as requested by the provider, depending upon the degree of laceration and provider preference.[50]

Promoting Relaxation and Rest During the Third Stage of Labor

The birth of a newborn stimulates a variety of emotions by the client and the partner, such as joy, excitement, fear, sadness, or trepidation. The nurse supports the client and partner through these emotions and promotes rest and relaxation. Promoting relaxation during the third stage of labor can be done in many ways, including the following[51]:

- Encouraging deep breathing

- Providing a calm, quiet environment

- Offering warm blankets

- Gently massaging the client’s abdomen

- Encouraging guided imagery to relax

- Offering emotional support and reassurance

Assessing the Newborn

Immediately upon birth, assessment of the newborn begins and will continue until the newborn is discharged. Initial observation allows the health care provider to monitor for any distress or complications. At one and five minutes of life, an Apgar score is assigned to the newborn using five specific parameters to evaluate the physiologic state of the newborn, including heart rate, respiratory effort, muscle tone, response to irritating stimuli, and color.

Review Apgar scoring in the “Applying the Nursing Process and Clinical Judgment Model to Newborn Care” section of the “Healthy Newborn Care” chapter.

Promoting Temperature Regulation, Adaptation, and Bonding

Monitoring and maintaining the newborn’s body temperature are essential to the transition to extrauterine life. At birth, the fetal body temperature is dependent on the maternal temperature. The delivery room temperature and the evaporation of fluid from the newborn’s skin result in a rapid drop in temperature (approximately 2° C) following birth and during the first half hour of life. In many cases, the newborn is placed on the client’s abdomen immediately after birth. After the cord is clamped, the newborn is moved up to the client’s chest to continue skin-to-skin contact and initiate breastfeeding within the first hour. This immediate contact has significant benefits, including temperature regulation and emotional bonding. Physiologic and metabolic adaptation and maintenance of glucose blood levels are also positively impacted when the newborn is placed skin-to-skin immediately and for their first hour of life. The attending nurse will also dry the newborn, apply a newborn hat, and cover them with warm blankets to assist in temperature regulation.[52]

In addition to the benefits of skin-to-skin for the transitioning newborn, skin-to-skin has positive effects for the client during the third stage of labor. Skin-to-skin contact causes maternal secretion of endogenous oxytocin, resulting in uterine contractions and decreasing the duration of the third stage of labor.[53]

While the newborn is on the client’s chest and before the expulsion of the placenta, the umbilical cord is clamped by the health care provider and cut by the partner, support person, or health care provider. Waiting 30 to 60 seconds for delayed cord clamping in newborns is associated with significant benefits to the newborn, including increased hemoglobin levels and improved circulation.[54]

In cases where skin-to-skin contact or delayed cord clamping is not feasible or possible, the newborn is placed in the infant warmer for further assessment and interventions.[55]

Monitoring for Complications

The nurse monitors for signs of complications in the newborn and the laboring client, including retained placenta, postpartum hemorrhage, and involution of the uterus.

Review the “Complications and Medical Interventions During the Third Stage of Labor” section for more information about retained placenta, postpartum hemorrhage, and involution of the uterus.

Review information about newborn complications in the “Common Complications During the Neonatal Period” section of the “Healthy Newborn Care” chapter.

Providing Health Teaching During the Third Stage of Labor

The nurse teaches the client about delivery of the placenta, relaxation techniques during the recovery period, the importance of skin-to-skin contact with the newborn, and monitoring for excessive bleeding that can indicate postpartum hemorrhage. Clients are advised to immediately notify the nurse if postpartum bleeding soaks through one or more menstrual pads in an hour or they pass blood clots larger than an egg. Clients are encouraged to breastfeed immediately after birth, not just for the benefits to the newborn, but due to the benefits of the natural release of oxytocin that assists with contraction of the uterus and reduces risk of PPH.[56],[57]

Nursing Care Immediately After Cesarean Birth

Cesarean birth may be planned or unplanned. The most common indication for unplanned cesarean birth is dystocia, meaning the client undergoes the first and/or second stage of labor but labor does not sufficiently progress and cesarean birth is required for the safety of the mother or fetus. In those cases, in addition to the nursing care previously described, the nurse also provides immediate postoperative care.

Nursing assessments immediately after cesarean birth are based on agency policy and provider orders. Head-to-toe assessments are typically performed every 15 minutes for the first hour, every 30 minutes during the second hour, and hourly thereafter until the client is transferred to the postpartum unit. Assessments and interventions include the following:

- Vital signs, including pulse oximetry with oxygen administered per nasal cannula as indicated.

- Cardiac monitoring.

- If regional anesthesia was administered, return of sensation and movement to the lower extremities is assessed; if general anesthesia was administered, return to level of consciousness is assessed.

- Pain assessment with administration of analgesics as ordered.

- Dressing over abdominal incision for drainage.

- Uterine fundus for firmness, height, and deviation. Fundal massage and uterotonic administration are initiated per provider orders if poorly contracted.

- Lochia for color, quantity, and presence of large clots. Postpartum hemorrhage is a priority concern.

- Urine output for color, quantity, and patency of the indwelling catheter.

- Intravenous site for patency and signs of infiltration.

The nurse initiates skin-to-skin care with the neonate as soon as it is safe to do so after surgery, optimally within one hour after delivery. The client is frequently encouraged to breathe deeply and cough, with a small pillow provided to splint the abdominal incision when coughing or turning.

Additional postpartum care for a client who underwent cesarean birth is discussed in the “Postpartum Care” chapter.

Evaluation (Evaluate Outcomes)

During the final stage of the nursing process, nurses evaluate the effectiveness of interventions to determine if outcome criteria have been met, partially met, or not met. The nursing care plan is revised as needed to effectively meet the established outcome criteria. For example, if a client reports the pain management plan is not effectively relieving her pain during labor, the nurse contacts the health care provider for additional orders and continues to re-evaluate the client’s pain level.

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Raines, D. A., & Cooper, D. B. (2023). Braxton-Hicks contractions. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470546/ ↵

- Raines, D. A., & Cooper, D. B. (2023). Braxton-Hicks contractions. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470546/ ↵

- Raines, D. A., & Cooper, D. B. (2023). Braxton-Hicks contractions. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470546/ ↵

- Healthdirect Australia Limited. (2023). Cultural practices and preferences when having a baby. Pregnancy, Birth and Baby. https://www.pregnancybirthbaby.org.au/cultural-practices-and-preferences-when-having-a-baby ↵

- Hutchison, J., Mahdy, H., & Hutchison, J. (2023). Stages of labor. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544290/ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Hutchison, J., Mahdy, H., & Hutchison, J. (2023). Stages of labor. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544290/ ↵

- Geeky Medics. (2019, September 21). Pregnant abdomen examination (a.k.a. obstetric abdominal examination) - OSCE guide | UKMLA | CPSA [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=-pkkgBX7OFQ ↵

- Herdman, T. H., Kamitsuru, S., & Lopes, C. T. (Eds.). (2021). Nursing diagnoses: Definitions and classification, 2021-2023 (12th ed.). Thieme. ↵

- Martin, P. (2023). 45 labor stages, induced and augmented, dystocia, precipitous labor nursing care plans. Nurslabs. https://nurseslabs.com/labor-stages-labor-induced-nursing-care-plan/#risk-for-altered-family-process ↵

- “labor-delivery” by George Ruiz is licensed under CC BY 2.0 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “22cd54ee2cedce7adc24bf7dc9cdcceb77982908” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/18-2-nursing-care-during-the-second-stage-of-labor ↵

- “12d769d08faf37baa947a62469f47fcfabe15c28” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/18-2-nursing-care-during-the-second-stage-of-labor ↵

- “Infant Warmer” by Open RN is licensed under CC BY 4.0 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “3077d55c23a9ea8bdeb353e82a992f88bedffb49” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/18-3-nursing-care-during-the-third-stage-of-labor ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “195eea31cd0fa049d3bef61e66828178fcc3b801” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/18-3-nursing-care-during-the-third-stage-of-labor ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Miles, K. (2023). Signs and treatment of postpartum hemorrhage. BabyCenter. https://www.babycenter.com/baby/postpartum-health/postpartum-late-hemorrhage_1456138 ↵

Burning sacred herbs to cleanse, purify, and connect with the spirit world.

A chromosomal disorder caused by an extra copy of chromosome 21 that can cause physical abnormalities and intellectual disabilities of the newborn.

A genetic disorder that affects the respiratory and digestive systems, leading to the production of thick mucus that can cause severe respiratory and digestive problems.

When a person inherits one normal hemoglobin gene (hemoglobin A) and one sickle cell gene (hemoglobin S). This means they carry the sickle cell gene but do not have the disease.

A genetic blood disorder characterized by the presence of abnormal hemoglobin, known as hemoglobin S. This abnormal hemoglobin causes red blood cells to become stiff, sticky, and shaped like a crescent or "sickle."

A rare genetic disorder that affects the nervous system and is more common in people of Ashkenazi Jewish descent.

A rare genetic disorder that affects the blood's ability to clot properly.

Severe birth defects of the brain and spine that occur when the neural tube, an embryonic structure that develops into the spinal cord and brain, doesn't close completely during pregnancy.

Structural problems with the heart that are present at birth.

Temporarily sewing the cervix closed to prevent preterm birth.

A long piece of cloth.

Clients take deep breaths in and exhale naturally as they feel the urge to bear down and push.

The client is instructed to hold their breath and push forcefully for a specified duration during each contraction.

May include pouring warm water over the perineum or using wet washcloths to cleanse the perineum moving from the pubic hair line to the anus using a front-to-back motion. A separate area of the washcloth should be used for each stroke to prevent contamination from the rectum to the vaginal area.

Set up that contains sterile drapes, bulb syringe, cord clamp, sponges, syringe for local anesthesia, delivery equipment, and instruments to complete repairs to the perineum if necessary.

Medications that increase the one and contractility of the uterus and are administered immediately following the birth of the newborn or delivery of the placenta.

A laceration of the labia and perineum affects the skin and subcutaneous tissue.

A laceration that affects the skin, subcutaneous tissue, and muscle of the perineum, as well as the vagina.

A perineal tear extends to or through the anal sphincter.

A laceration which includes damage to the pelvic floor and surrounding anal and rectal mucosa.

Waiting 30 to 60 seconds to clamp the umbilical cord.