18.16 Pelvic Floor Disorders

The pelvic floor is the term applied to the group of muscles that provide support to the organs located in the pelvis, including the uterus, urinary bladder, and bowel. Decreased strength of the pelvic floor muscles can cause pelvic organ prolapse that interferes with their function, causing pain, leaking of urine or stool, constipation, feelings of fullness in the vagina, and difficulty defecating. Conditions that decrease the integrity of the pelvic muscular structures are called pelvic floor disorders. The symptoms of these disorders can affect a person’s quality of life by causing them to avoid social interactions and sexual activity.[1]

Factors that increase the incidence of pelvic floor disorders include pregnancy, vaginal delivery, increased number of deliveries, connective tissue disorders, obesity, chronic constipation, and hysterectomy. Many pelvic floor disorders go undiagnosed and untreated. Some people do not seek treatment because they are embarrassed to discuss their symptoms with a health care provider. Other clients may mistakenly believe their symptoms are a normal part of aging.[2]

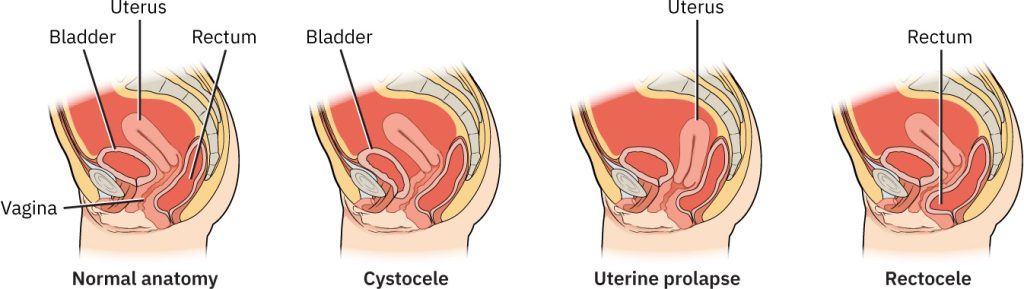

There are many types of pelvic floor disorders, including cystocele, rectocele, and uterine prolapse. Figure 18.16[3] illustrates these types of pelvic organ prolapse.

- A cystocele occurs when the bladder bulges into the anterior wall of the vagina. Symptoms may include vaginal pressure, a feeling of fullness, decreased sexual satisfaction, lower back pain, urinary frequency, urinary urgency, and urinary retention that may lead to frequent urinary tract infections.[4]

- A rectocele occurs when the rectum bulges into the posterior wall of the vagina. Symptoms include vaginal pressure, a feeling of fullness, the feeling that something is falling down or out of the pelvis, lower back pain, decreased sexual satisfaction or pain, constipation, trouble with stool becoming trapped in the rectocele, and other symptoms of urinary dysfunction.[5]

- A uterine prolapse occurs when the pelvic floor can no longer support the uterus, and the uterus descends into the vagina. Symptoms of uterine prolapse include urinary incontinence, feeling of fullness in the vagina, bulging of the vagina, constipation, and back pain.[6]

Diagnosis of pelvic floor disorders is based on a physical examination by the health care provider and diagnostic testing to rule out urinary tract infection or other infections. Once it has been determined that the problem is functional, the health care provider will assess the impact the condition has on the client’s emotional, physical, and social life. One method of assessment is administering a pelvic floor questionnaire. Pelvic floor questionnaires evaluate feelings of pressure, bulging, difficulty in passing stool, incontinence of urine or stool, and pain. These self-scoring tools assist the provider in understanding the goals of the client and can help to guide the treatment. Additional diagnostic testing, such as cystoscopy, urodynamics, and colonoscopy, can also assist in diagnosing the severity of the condition.[7]

Medical management of cystocele, rectocele, and uterine prolapse has many similarities. Treatment includes pelvic floor strengthening exercises (also called Kegel exercises), hormone replacement therapy, pessary insertion, or surgical repair.[8]

To perform Kegel exercises, the client is instructed to squeeze the muscles of the pelvic floor and contract the muscles around the urethra, vagina, and rectum in an upward motion. This muscle contraction should feel similar to the action of trying to stop the flow of urine. Clients should start by performing ten repetitions, three times per day. If a client is experiencing urinary incontinence, the nurse can suggest working up to 30 repetitions, three times a day for three months. If Kegel exercises do not resolve the urinary incontinence, pelvic floor therapy may be needed.[9]

View a supplementary YouTube video[10] on how to perform Kegel exercises: How To Do A Kegel Exercise – Step by Step Instructions.

View additional videos on pelvic floor exercises at https://nafc.org/pelvic-floor-exercise-videos/.

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is a medical treatment where a person takes medications containing hormones that their body is no longer producing in sufficient amounts. HRT may contribute to increased pelvic muscle tone, vaginal elasticity, and integrity. However, there are risks associated with hormone replacement therapy, and not all clients are candidates for therapy. Read more about HRT in the “Perimenopause and Menopause” section.

A pessary is a device worn inside the vagina to provide support to the pelvic floor muscles and organs. Pessaries are made of medical-grade silicone and come in many different sizes and shapes. It is not uncommon for a client to be fitted for multiple sizes and shapes of pessaries before finding the most comfortable and effective fit. See Figure 18.17[11] for an image of different types of pessaries.[12]

Most pessaries can be worn for several days, including during intercourse, before removing them to clean with soap and water. Clients may be able to take out the pessary, clean it, and reinsert it, or they may have scheduled appointments with a health care provider to do so. Clients may notice more vaginal discharge than normal when using a pessary, and it may develop an odor. Nurses can teach clients that certain vaginal gels can help with these side effects. Menopausal women may also need to use estrogen cream to help relieve vaginal irritation caused by the pessary.[13]

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “347ce58449033949d8939dd779cfdee30ae4bf1e” by Rice University/Open Stax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/6-2-structural-disorders ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Stratton, K. (2023). Kegel exercises - self-care. MedlinePlus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000141.htm ↵

- BHealth. (2022, October 18). How to do a Kegel exercise - Step by step instructions [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Usf5RT57vQY ↵

- “Pessaries.JPG” by Huckfinne is in the Public Domain. ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

Conditions that decrease the integrity of the pelvic muscular structures.

A condition where the bladder bulges into the vagina, often due to weakened pelvic muscles, which can lead to urinary incontinence.

A condition in which the rectum bulges into the vaginal wall due to weakened pelvic muscles.

A condition where the uterus descends from its normal position into the vaginal canal due to weakened pelvic muscles and ligaments, often caused by childbirth, aging, or other factors that weaken pelvic support.

Pelvic floor muscle exercises.

A medical treatment where a person takes medication containing hormones to replace those that their body no longer produces in sufficient amounts.

A device worn inside the vagina to provide support to the pelvic floor muscles and organs.