18.14 Infertility

Infertility is the inability to conceive after 12 months of unprotected sexual intercourse or after six months of unprotected intercourse for women over 35 years old. It also refers to the inability of a woman to carry a pregnancy to live birth. Infertility affects millions of people around the world and can also impact their families and communities. Estimates suggest that approximately one in every six people of reproductive age worldwide experience infertility in their lifetime. In the male reproductive system, infertility is most commonly caused by problems in the ejection of semen, low levels or absences of sperm production, or abnormal morphology (shape) or motility (movement) of sperm. In the female reproductive system, infertility may be caused by a variety of abnormalities of the ovaries, uterus, Fallopian tubes, and the endocrine system. In some cases, a specific cause for a couple’s infertility cannot be determined. Infertility is classified as primary or secondary. Primary infertility is when a pregnancy has never been achieved by a person, and secondary infertility is when at least one prior pregnancy has been achieved.[1]

Causes of Infertility in the Male Reproductive System

Many factors, including hormonal, structural, infectious, and genetic causes, can cause infertility in the male reproductive system. These factors are further discussed in the following subsections.

Hormonal Causes of Infertility

Abnormalities in hormones produced by the pituitary gland, hypothalamus, or testes, such as testosterone, luteinizing hormone, follicle-stimulating hormone, and prolactin, can lead to the poor production of sperm. Hormonal abnormalities can be caused by pituitary or hypothalamic disease or tumors, certain prescribed medications or illicit drugs, and hyperthyroidism. Low testosterone levels and testosterone supplementation can significantly reduce sperm production.[2]

Alterations in Spermatogenesis

Spermatogenesis is the production and maturation of sperm cells in the testes. Exposure to some toxins known as gonadotoxins can reduce the ability of the testes to make healthy, motile sperm cells. Potential gonadotoxins include certain medications, illicit drugs, infection, chronic illness, exposure to chemicals, radiation, chemotherapy, or exposure of the testicles to heat (such as wearing tight clothing or sitting in a hot tub). Opioids can cause hypogonadism (where testes don’t produce enough testosterone). These factors can cause azoospermia (the complete absence of sperm cells) or oligospermia (a low sperm count).[3]

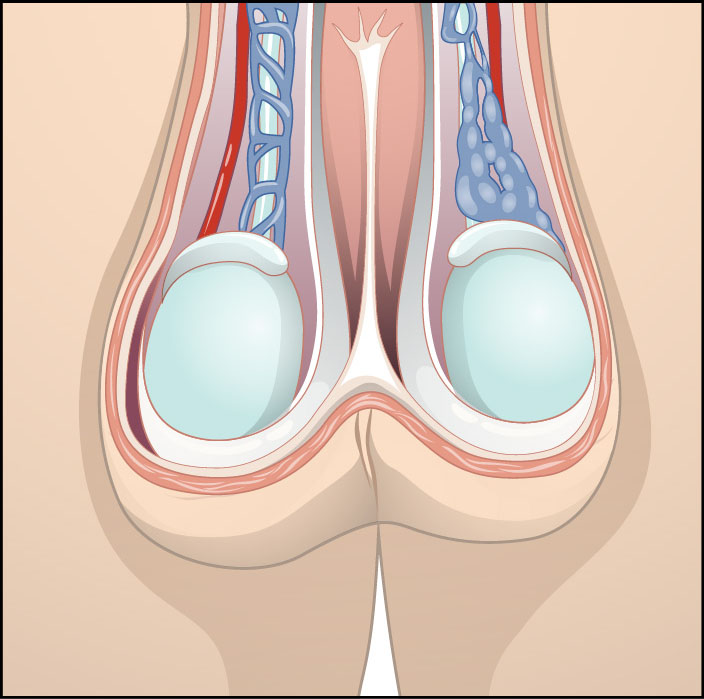

Varicoceles may also impact spermatogenesis. A varicocele is a tortuous enlargement of the scrotal veins, similar to varicose veins, in the testicle. See Figure 18.11[4] for an illustration of a varicocele. While most varicoceles do not cause problems, they can cause decreased sperm counts. The exact mechanism of action is unknown, but it is hypothesized that the pooling of blood in the enlarged veins may raise scrotal temperature.[5]

Issues With Sperm Transport

Blockages in the vas deferens or ejaculatory ducts can prevent the release of sperm cells during ejaculation or the transport of sperm through the reproductive tract. These blockages can be caused by the following conditions[6]:

- Scar tissue after surgery, trauma, or injury

- Infection

- A tumor that compresses the reproductive structures

- A vasectomy

- Congenital absence of the vas deferens

Erectile or ejaculatory disorders can also prevent the transmission of sperm into the female reproductive tract. These disorders are frequently caused by aging or chronic illness, such as hypertension or diabetes. Retrograde ejaculation, the backward movement of semen into the bladder instead of being expelled from the urethra, can also contribute to a low sperm count in the ejaculated semen.[7]

Presence of Sperm Antibodies

Sperm antibodies are produced when the immune system does not recognize sperm cells as part of the body and initiates an immunologic reaction. This reaction damages sperm cells and may make them immotile (e.g., unable to move). While not common, this condition does occur in some clients after testicular trauma, infections, or vasectomy reversal.[8]

Causes of Infertility in the Female Reproductive System

Many factors, including hormonal, structural, infectious, and genetic conditions, can cause infertility in the female reproductive system. These factors are further discussed in the following subsections.

Hormone and Ovulatory Dysfunction

Ovulatory dysfunction is the largest cause of female infertility. If an ovum is not released by the ovary on a regular basis, there is no opportunity for fertilization or conception. The two main types of ovulatory dysfunction are oligoovulation, a pattern of irregular ovulation, and anovulation, the complete absence of ovulation, meaning the ovary does not release an ovum during the menstrual cycle.[9]

There are four classifications of ovulatory dysfunction[10]:

- Hypogonadotropic hypogonadal anovulation: A condition where decreased secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) suppresses the secretion of FSH and LH from the anterior pituitary gland, causing low estrogen, poor follicular growth, and anovulation. Also known as hypothalamic amenorrhea, this condition is most common in people with eating disorders due to excessive exercise, decreased caloric intake, or significant weight loss.

- Normogonadotropic normoestrogenic anovulation: A type of ovulatory disorder characterized by normal levels of gonadotropins and estrogen but the absence or irregularity of ovulation. This is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility and is often associated with conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS). Women with PCOS often do not ovulate regularly due to an abnormal release of GnRH, which leads to dysfunction in developing a mature follicle. Read more about PCOS in the “Polycystic Ovary Syndrome” section.

- Hypergonadotropic hypoestrogenic anovulation: This type of anovulation is associated with the natural aging process, as well as primary ovarian insufficiency (POI), defined as ovarian failure before the age of 40. The number and quality of eggs that a woman is born with decrease with age. Cigarette smoking is also associated with premature menopause and decreased numbers of ovarian follicles. POI also occurs in individuals with Turner syndrome, a genetic syndrome that causes a missing sex chromosome, either an X or a Y, that determines if an individual is born with male or female physical characteristics. People with Turner syndrome appear physically female.

- Hyperprolactinemic anovulation: Elevated serum prolactin levels lead to suppression of GnRH from the hypothalamus; low LH, which causes anovulation and amenorrhea; and poor progesterone secretion from the corpus luteum. Normal prolactin levels are typically under 20 ng/mL. Serum levels above 100 ng/mL are associated with benign tumors of the pituitary gland.

Endometrial or Uterine Problems

Structural problems in the uterus can also prevent pregnancy due to lack of implantation of the embryo. Structural problems include the following[11]:

- Uterine fibroids: Most fibroids do not affect fertility, but very large fibroids or those that protrude into the endometrial cavity can make conception more difficult. Read more about fibroids in the “Fibroids” section.

- Endometrial polyps: The effect of endometrial polyps on fertility is not clear. While many people with an endometrial polyp can successfully carry a pregnancy to term, research suggests that removing them may be beneficial before proceeding with fertility treatment, particularly in vitro fertilization (IVF). Read more about endometrial polyps in the “Endometrial Polyps” section.

- Endometriosis: Endometriosis can cause scar tissue or adhesions that block sperm or the egg from reaching the Fallopian tube for fertilization to take place. Read more about endometriosis in the “Endometriosis” section.

- Scarring: Scarring from previous trauma, surgeries, infections, or endometriosis can block the passage of sperm through the uterus or the movement of a fertilized egg into the uterus. It can also prevent implantation and may increase the risk for ectopic pregnancy elsewhere in the reproductive tract.

- Endometritis: Endometritis is an inflammation or infection of the endometrial lining of the uterus that can prevent implantation.

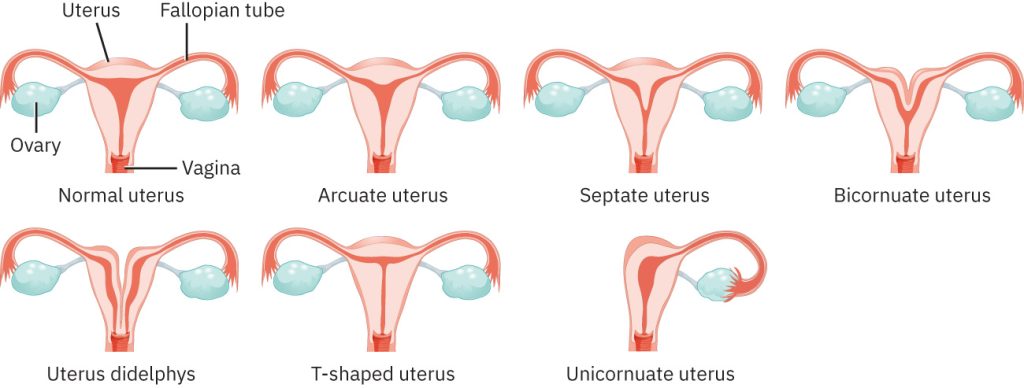

- Abnormal uterine shape: Congenital abnormalities can cause many different shapes and conformations of the uterus. Depending on the extent of the abnormality, sperm may not be able to reach the egg, or implantation of a fertilized egg may not be possible. See Figure 18.12[12] for an illustration of congenital abnormalities of the uterus.

Tubal Issues

Blockages in the Fallopian tube(s), also known as tubal occlusion, can prevent sperm cells from reaching the egg. These blockages can result from several factors, including the following[13]:

- Infection

- Inflammation

- Scar tissue from endometriosis or previous pelvic or abdominal surgery

- Adhesions

- Structural issues

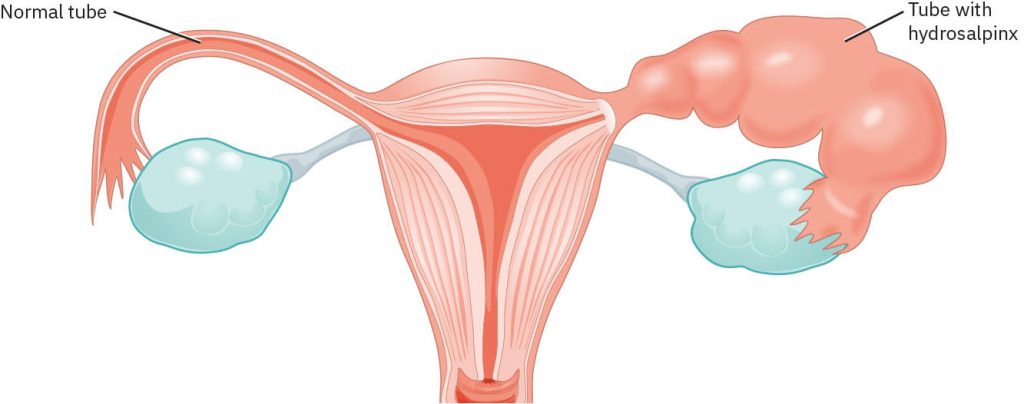

A hydrosalpinx is a condition where the Fallopian tube becomes filled and blocked with fluid. Like a blockage from scar tissue, it prevents movement of sperm and eggs and results in infertility. See Figure 18.13[14] for an illustration of a hydrosalpinx. Hydrosalpinx also increases the risk for ectopic pregnancy, where a fertilized egg implants outside the uterus, most commonly in the Fallopian tube. The risk factors for developing a hydrosalpinx are the same as for a tubal blockage, including infection, pelvic inflammatory disease (PID), and scar tissue or adhesions from prior abdominal surgery.[15]

Other Causes of Infertility

Other potential causes of infertility include stress, environmental factors, and societal beliefs related to parenthood[16]:

- Stress: Many individuals coping with infertility report high levels of stress. Stress increases levels of cortisol that may contribute to infertility. Interventions such as cognitive behavior therapy, relaxation training, lifestyle changes, journaling, and support groups can help reduce stress and improve the chances of conception.

- Environmental Factors: Many environmental factors can influence the health of the egg, sperm, and uterus, such as pesticides, radiation, and contaminated water. Nurses can help educate clients about these risks and promote environmental health.

- Societal Beliefs Related to Parenthood: Changes in societal beliefs have impacted family-building practices in the United States and globally. Couples may choose to wait to become parents for several reasons, such as furthering their education, advancing their careers, or building financial resources. The median age at which women gave birth in the United States shifted from 22.4 years in 1979 to 26.9 years in 2016.[17] As the female partner ages beyond age 30, the chance of conception decreases. See Table 18.14a for the average chance of conception for couples within one year based on the age of the female partner.

Table 18.14a. Chance of Conception Within 1 Year Based on the Age of the Female Partner[18]

| Age of Female Partner | Average Chance of Conception Within 1 Year |

|---|---|

| Less than 30 Years Old | 85% |

| 30 Years Old | 75% |

| 35 Years Old | 66% |

| 40 Years Old | 44% |

Interventions to Improve Fertility

Nurses provide health teaching on how to optimize fertility to couples desiring to conceive. Teaching topics vary for those who are just starting on the journey of trying to conceive to those undergoing advanced infertility treatments. Table 18.14b summarizes suggestions that nurses can provide to improve male and female fertility.[19]

Table 18.14b. Practices to Improve Fertility[20]

| Practices | Rationale |

|---|---|

| Maintain a healthy weight. |

|

| Avoid alcohol, tobacco, and recreational drugs. |

|

| Reduce caffeine consumption. |

|

| Prevent sexually transmitted infections (STIs). |

|

| Avoid exposure to toxins. |

|

| Eat a healthy, antioxidant diet rich in fruits, vegetables, lean protein, and whole grains. |

|

| Stay hydrated. |

|

| Monitor ovulation. |

|

| Exercise regularly. |

|

| Avoid raising scrotal temperature. |

|

Coital practices can also improve a couple’s ability to conceive. Teaching points may include the following[21]:

- Track ovulation by using basal body temperature, ovulation predictor kits, or monitoring cervical mucus. The fertile period begins up to a week before ovulation and continues until the day after ovulation occurs. Couples should have intercourse at least every other day during this window.

- Lubricants, including saliva, olive or coconut oil, and other commercial products, should be avoided because of their effect on sperm. If necessary, obtain a lubricant specifically intended for couples trying to conceive.

- No evidence indicates coital position increases or decreases the odds of conception.

Infertility Medications

Medications may be prescribed to regulate or stimulate ovulation. Examples of fertility medications include the following[22]:

- Clomiphene citrate: Stimulates ovulation by causing the pituitary gland to release more FSH and LH hormones, which stimulate the growth of ovarian follicles containing and ovum. This is generally the first line of treatment for women younger than age 39 who don’t have polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

- Aromatase inhibitors: Aromatase inhibitors such as letrozole work in a similar manner as clomiphene citrate and prescribed to women younger than age 39 who have PCOS.

- Metformin: Metformin is typically prescribed to women diagnosed with PCOS to improve insulin resistance and the likelihood of ovulation.

- Gonadotropins: Injected gonadotropin medications such as human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG) and FSH stimulate the ovary to produce multiple eggs. Human chorionic gonadotropic is prescribed to mature the eggs and trigger their release at the time of ovulation. Risks include conceiving multiples and having premature delivery.

- Bromocriptine: Bromocriptine is a dopamine agonist used when ovulatory dysfunction is caused by hyperprolactinemia.

Infertility Procedures

Infertility treatments may be performed for clients who do not conceive within one year of attempting fertility practices, such as intrauterine insemination, assisted-reproductive technology, and gestational carriers.

Intrauterine insemination (IUI), also called artificial insemination, is a procedure where specially prepared sperm are inserted into the woman’s uterus by the health care provider. In some cases, the woman is also pretreated with medications that stimulate ovulation before IUI. IUI is typically used to treat mild male factor infertility or in couples with unexplained infertility.[23]

Assisted-reproductive technology (ART) includes all fertility treatments in which either eggs or embryos are handled outside of the body. In general, ART procedures involve removing mature eggs from a woman’s ovaries using a needle, combining the eggs with sperm in the laboratory, and returning the embryos to the woman’s uterus. Embryos may also be donated to other women experiencing infertility, implanted in a gestational carrier/surrogate, or frozen for future use after medical treatments such as chemotherapy. Success rates vary and depend on many factors, including the clinic performing the procedure, the infertility diagnosis, and the age of the woman undergoing the procedure. ART can be expensive and time-consuming, but it has allowed many couples to have children who otherwise would not have been conceived. The most common complication of ART is a multiple pregnancy with additional risks related to preterm birth.[24]

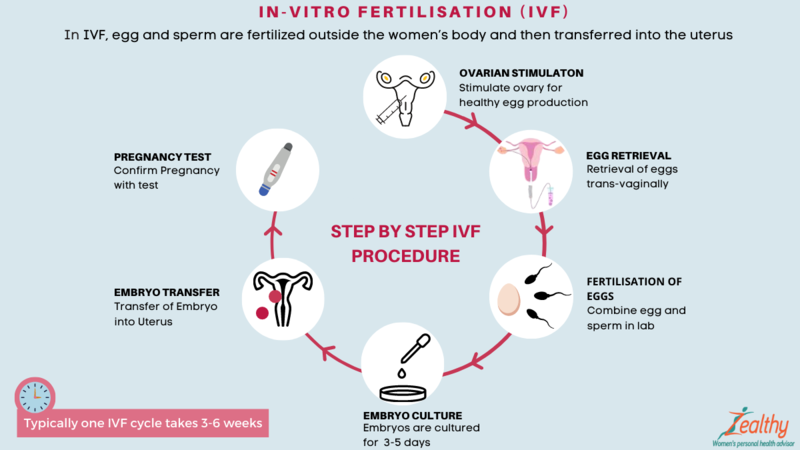

ART treatments include in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI).

In both treatments, fertilization occurs in a laboratory to create embryos outside of the woman’s body. During IVF, eggs and sperm are combined in a laboratory dish and sperm fertilize each egg. ICSI is a type of IVF that is often used for couples with male factor infertility. During ICSI, a single sperm is injected into a mature egg. After about three to five days, the embryo (or embryos) is transferred into the woman’s uterus. Embryos can also be frozen for a future transfer. When a frozen embryo is thawed and transferred into a woman’s uterus, it is called a frozen embryo transfer.[25] See Figure 18.14[26] for an illustration of IVF.

ART procedures may involve the use of donor eggs (eggs from another woman), donor sperm (sperm from another man), or donated embryos. Donor eggs and sperm are used for women who cannot produce eggs or men who cannot produce sperm or if either partner has a genetic disease that can be passed on to the infant. An infertile couple may also use donated embryos that were created for other couples undergoing infertility treatment but were not used. When donated embryos are used, the child will not be genetically related to either parent. Donor eggs, sperm, or donated embryos may also be used by same-sex couples.[27]

Couples may elect to use a gestational carrier, also called a surrogate mother, who is impregnated through in vitro fertilization and delivers an infant for them to parent. Surrogacy may also be an option for women who have a serious health problem where pregnancy is contraindicated or if they are unable to conceive. If the female partner has healthy eggs and the male partner has healthy sperm, the egg is fertilized by the male partner’s sperm, and the embryo is placed inside the gestational carrier’s uterus. Alternatively, donor eggs, sperm, or embryos may also be used.[28]

Read more about gestational surrogacy in the “Family Adaptations During Childbirth” section of the “Labor & Delivery Care” chapter.

View a supplementary YouTube video[29] about the difference between in vitro fertilization (IVF) and intracytoplasmic sperm injection: What is the Difference Between IVF & ICSI (Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection)?

- World Health Organization. (2024). Infertility. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/infertility#:~:text=Infertility%20is%20a%20disease%20of,types%20of%20medically%20assisted%20reproduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Office on Women’s Health. (2021). Endometriosis. https://womenshealth.gov/a-z-topics/endometriosis ↵

- “9c730d69b2f8a1d9f8104890bf81a678858a8d69” by Rice University/Open Stax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/4-3-causes-of-infertility#fig-00002 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “dc60a6992e1ef3490840661e5384ec06a09e4093” by Rice University/Open Stax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/4-3-causes-of-infertility#fig-00002 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “fb604d781ef2df4cdf18fe444c1fa2c32d1098ba” by Rice University/Open Stax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/4-3-causes-of-infertility#fig-00002 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Hemez, P. (2019). Family formation experiences: Women’s median ages at first marriage and first birth, 1979 & 2016. National Center for Family & Marriage Research (NCFMR), Family Profile No. 16. https://doi.org/10.25035/ncfmr/fp-19-16 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2021). Female infertility. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/female-infertility/diagnosis-treatment/drc-20354313 ↵

- Division of Reproductive Health. (2024). Infertility: Frequently asked questions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductive-health/infertility-faq/ ↵

- Division of Reproductive Health. (2024). Infertility: Frequently asked questions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductive-health/infertility-faq/ ↵

- Division of Reproductive Health. (2024). Infertility: Frequently asked questions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductive-health/infertility-faq/ ↵

- “In_Vitro_Fertilization_(IVF)_-_English.png” by https://zealthy.in/en is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Division of Reproductive Health. (2024). Infertility: Frequently asked questions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductive-health/infertility-faq/ ↵

- Division of Reproductive Health. (2024). Infertility: Frequently asked questions. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductive-health/infertility-faq/ ↵

- Allahbadia, G. 2023, June 12). What is the difference between IVF & ICSI (Intracytoplasmic Sperm Injection)? [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iu1IHiwI0J8 ↵

The inability to conceive after one year of unprotected intercourse or six months for women over 35 years old, or the inability to carry a pregnancy to live birth.

When a pregnancy has never been achieved by a person.

When at least one prior pregnancy has been achieved.

The process by which sperm are produced and matured in the testes.

Toxins which can reduce the ability of the testes to make healthy, motile sperm cells.

The complete absence of sperm cells.

A low sperm count.

An enlargement of veins within the scrotum, similar to varicose veins, which can affect fertility.

Referring to the backward movement of semen into the bladder instead of being expelled from the urethra, can also contribute to a low sperm count.

A pattern of irregular ovulation.

The absence of ovulation, when the ovary does not release an egg during the menstrual cycle.

Decreased secretion of gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) suppresses the secretion of FSH and LH from the anterior pituitary gland, causing low estrogen, poor follicular growth, and anovulation.

A type of ovulatory disorder characterized by normal levels of gonadotropins and estrogen but the absence or irregularity of ovulation. This is the most common cause of anovulatory infertility and is often associated with conditions such as polycystic ovary syndrome (PCOS).

This type of anovulation is associated with the natural aging process, as well as primary ovarian insufficiency (POI), defined as ovarian failure before the age of 40.

Elevated serum prolactin levels lead to suppression of GnRH from the hypothalamus; low LH, which causes anovulation and amenorrhea; and poor progesterone secretion from the corpus luteum.

A condition where the fallopian tube becomes filled and blocked with fluid.

Also called artificial insemination, is a procedure where specially prepared sperm are inserted into the woman’s uterus by the health care provider.

Includes all fertility treatments in which either eggs or embryos are handled outside of the body.

Also called surrogate mother, a woman impregnated through in vitro fertilization and delivers a child for a couple or individual.