11.4 Postpartum Complications

Postpartum complications typically occur from birth to six weeks after delivery, and some can occur up to one year after birth. The nurse plays a vital role in identifying potential complications and promptly notifying health care providers to promote optimal outcomes.

Infection

The risk for infection is highest in postpartum clients with a history of sexually transmitted infection, chorioamnionitis, prolonged rupture of membranes, or third- or fourth-degree lacerations. Clients with a body mass index (BMI) ≥ 30 have higher risk of developing postpartum infections, especially wound infections.

There are several common infections that may occur during the postpartum period, including endometritis, mastitis, urinary tract infection, and wound infection. The nurse monitors for signs of infection and provides health teaching regarding prevention and treatment. Nurses are aware that any type of infection can lead to sepsis. Sepsis is a life-threatening condition where the body’s immune system overreacts to an infection, causing widespread inflammation and potential organ damage. If a client has an infection, nurses closely monitor for early signs of systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) that include the following[1]:

- Temperature over 38 or under 36 degrees Celsius

- Heart rate greater than 90 beats/minute

- Respiratory rate greater than 20 breaths/minute or PaCO2 less than 32 mmHg

- White blood cell count greater than 12,000 or less than 4,000 /microliters or over 10% of immature forms (bands)

A client with sepsis may also demonstrate decreased level of consciousness; warm, clammy skin; intense fatigue; pain; or loss of function of the affected part of the body. If untreated, sepsis can lead to septic shock, a life-threatening decrease in blood pressure (systolic pressure <90 mm Hg) that prevents cells and other organs from receiving enough oxygen and nutrients, causing multi-organ failure and death.[2]

Endometritis

Endometritis is an infection of the uterus. Risk factors include prolonged rupture of membranes, chorioamnionitis, and cesarean birth. Signs include uterine pain, foul-smelling lochia, increased vaginal bleeding, and fever. The nurse notifies the health care provider of signs of suspected infection and administers prescribed antibiotics and antipyretics.[3]

Mastitis

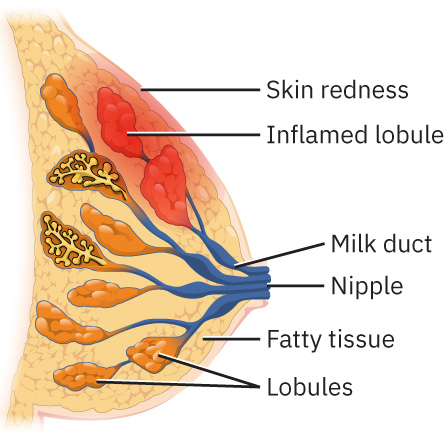

Mastitis is inflammation and/or infection of the breast associated with breastfeeding. Causes of mastitis include engorgement, clogged ducts, or nipple trauma due to incorrect latch during breastfeeding. Clogged ducts can be caused by compression of the breast by constrictive clothing that causes the milk to collect in the duct and creates a painful, firm area of the breast. An incorrect nursing latch can cause cracks or fissures in the nipple that permit entry of bacteria. Symptoms of mastitis include fever; chills; flu-like symptoms; and a painful, hot, reddened area of the breast.[4] See Figure 11.10[5] for an illustration of mastitis.

The nurse notifies the health care provider of suspected mastitis for anticipated prescription of antibiotics. If the client is breastfeeding, the nurse encourages feeding the infant every two to three hours to empty the breasts and avoid engorgement. If the breasts are too painful for breastfeeding, the client can try to breast pump to empty the breasts. Cool or warm compresses can be applied to the reddened area, and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) or acetaminophen can be taken for pain management.[6]

To prevent mastitis, nurses routinely assess nipples for cracking or redness and observe breastfeeding for a good latch. Nurses reinforce how to establish a good latch and advise if the latch hurts, to remove the baby and relatch. Referrals to a lactation consultant are made as indicated. Nipple ointment or expressed breastmilk may be applied if nipples are cracked or red to try to prevent mastitis.[7]

Read more information about breastfeeding and establishing a good latch in the “Breastfeeding Support” subsection of “Provide Postpartum Health Teaching” in the “Nursing Interventions” subsection of “Applying the Nursing Process and Clinical Judgment Model to Postpartum Care” section.

Urinary Tract Infection

Urinary tract infections (UTIs) are common postpartum infections. UTIs are associated with urinary retention after delivery and/or placement of an indwelling urinary catheter during labor. Signs and symptoms of a UTI include urinary frequency in small amounts, urgency, dysuria, hematuria, fever, and pain. If the UTI has ascended to the kidneys, the client may have costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness, high fever, nausea, and chills. The nurse notifies the health care provider of signs of a UTI, and urinalysis and/or urine culture and sensitivity is typically ordered. The nurse administers prescribed antibiotics and antipyretics and reviews culture and sensitivity lab results for antibiotic resistance. Health teaching includes increasing water intake; voiding frequently and not ignoring the urge to urinate; finishing antibiotics as prescribed; performing perineal hygiene and wiping from front to back; and notifying the health care provider of worsening symptoms such as increased fever, worsening suprapubic or flank pain, or flu-like symptoms.[8]

Wound Infection

Postpartum wound infections can occur from bacteria that ascended from the vagina, colonized on the skin, or were introduced during a cesarean birth. Typical wound sites are perineal lacerations, episiotomy repair sites, or an abdominal incision after a cesarean birth. Signs of postpartum wound infections are similar to perioperative wound infections and include redness, pain, and purulent drainage from the site, temperature greater than 100.4° C, and fatigue. The nurse notifies the health care provider of signs of a suspected wound infection and administers prescribed antibiotics. Health teaching is provided to the client to keep the site clean and dry, to wash their hands before and after touching the incision area, and to call the health care provider for worsening signs of infection after discharge.[9]

Postpartum Hemorrhage

Postpartum hemorrhage (PPH) is one of the most common complications of birth, occuring after one to five percent of births.[10] PPH is defined by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) as 1,000 mL of blood loss within 24 hours of birth for both vaginal and cesarean births.[11]

PPH that occurs after delivery of the placenta and up to 24 hours postpartum is considered early PPH. The mnemonic for the Four Ts of PPH helps recall the common causes of early PPH:

- Tone: Uterine atony is the most common cause of PPH

- Trauma: Lacerations or uterine rupture

- Tissue: Retained placenta, blood clots, or placenta accreta

- Thrombin: Clotting-factor disorder

Review information about early PPH in the “Complications and Medical Interventions During the Third Stage of Labor” section of the “Care Throughout Labor and Delivery” chapter.

PPH that occurs after 24 hours following delivery of the placenta and up to 12 weeks postpartum is considered late PPH. The most common cause of late PPH is uterine subinvolution (inability of the uterus to return to its original size). At the six-week postpartum follow-up, subinvolution may be diagnosed when the client’s uterus is larger than expected and lochia has not progressed to lochia alba. Other causes of late PPH are retained placenta or membranes and coagulation disorders.

Assessment: Recognizing Cues of PPH

Nurses caring for postpartum clients must be able to recognize the signs and symptoms of postpartum hemorrhage by accurately assessing blood loss, as well as monitoring for early signs and symptoms of hypovolemia. However, estimating blood loss can be difficult because blood is mixed with amniotic fluid. Nurses perform quantitative blood loss (QBL), a process of weighing and measuring the amount of blood lost during childbirth and the immediate postpartum period. To accurately perform QBL, birthing facilities provide scales for weighing sponges, menstrual pads, and disposable bed pads.[12],[13]

Nurses are aware that pregnant clients have 50 percent more blood volume than a nonpregnant person, so they may not exhibit signs of hypovolemia until they have lost a significant amount of blood. Early symptoms and signs of hypovolemia include decreased blood pressure; increased pulse and respiratory rates; and symptoms of weakness, dizziness, and anxiety. Severe hypovolemia causes tachycardia, hypotension, decreased oxygen saturation levels, low body temperature, decreased urinary output, restlessness, and thirst. If a client develops hypovolemic shock, they become diaphoretic and pale with cool clammy skin, confused, and may lose consciousness.[14],[15]

During PPH, the vessels of the extremities contract to shunt blood to the lungs, heart, and brain, so peripheral perfusion is decreased. The nurse assesses capillary refill and applies warm blankets to keep the client’s body and extremities warm. The client is positioned with their legs elevated and fluid and/or blood products are administered. Oxygen saturation levels are monitored, and supplemental oxygen is administered and titrated as prescribed.[16]

Many childbirth settings have implemented PPH protocols to standardize the recognition and management of PPH by the interprofessional health care team. See sample PPH guidelines in the following box. PPH medical management is discussed in the following subsection.[17],[18]

See sample PPH Care Guidelines from the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative.[19]

Interventions for PPH

Because uterine atony is the most common cause of early PPH, interventions to induce uterine contractions are quickly performed, including fundal massage and administration of uterotonics. Intrauterine tamponade may be performed. If these efforts are unsuccessful, an emergency hysterectomy is performed. These interventions are further discussed in the following subsections.

Fundal Massage

Fundal massage is the technique of massaging the uterus to stimulate contractions to decrease postpartum bleeding. The nurse places one hand on the fundus (top of the uterus) while the other hand supports the lower uterine segment near the symphysis pubis to prevent uterine inversion during the procedure. The nurse applies firm pressure to the fundus between the hands to induce a uterine contraction and stop the blood from pumping out of the spiral arteries. The goal of massage is to cause the uterus to contract into the size of a small, firm ball.[20] See Figure 11.11[21] for an illustration of fundal massage.

View a supplementary YouTube video[22] on performing fundal massage: Uterine Massage Technique.

Medications Used to Treat PPH

Several uterotonic medications may be prescribed to treat PPH. Common uterotonics include the following[23]:

- Oxytocin: Intravenous (IV) oxytocin infused as a bolus is typically the first-line medication to treat PPH. It can also be administered intramuscularly (IM) when IV access is not available. The goal is to stimulate contractions to resolve uterine atony. Oxytocin has a boxed warning and is classified as a high-risk medication by the Federal Drug Association (FDA). Maternal deaths have been reported due to hypertensive episodes, subarachnoid hemorrhage, or rupture of the uterus. A uterus that has been scarred from a previous cesarean birth or myomectomy (surgical removal of uterine fibroids) is at higher risk of rupture. Other side effects include a fast or irregular heart rate, headache, fluid retention, nausea, and vomiting.[24]

- Misoprostol: Misoprostol is a prostaglandin used to treat PPH and induces uterine contractions. It may be administered orally, rectally, or sublingually. Misoprostol is a safe prostaglandin to administer to clients with asthma and hypertension, but it should be administered cautiously to clients with cardiovascular disease. Common side effects include diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, and headache.[25]

- Methylergonovine: Methylergonovine acts directly on the uterine muscle and is the only uterotonic that causes sustained contractions instead of rhythmic contractions. It is administered IM or orally but should not be given IV because of the possibility of inducing sudden hypertensive and cerebrovascular accidents. It should not be administered to clients with hypertension or preeclampsia. Mothers should not breastfeed during treatment with methylergonovine, and milk secreted during this period should be discarded. The most common side effects are hypertension associated with seizure and/or headache. Hypotension, nausea, and vomiting have also been reported.[26]

- Carboprost: Carboprost is a strong prostaglandin that is administered IM and can also be administered directly into the muscle of the uterus by a health care provider in severe cases of PPH. It is contraindicated in clients with active cardiac, pulmonary, renal, or hepatic disease. Side effects are related to its contractile effect on smooth muscle, including nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, increased temperature, and flushing. Concurrent administration of antipyretics, antiemetics, and antidiarrheal medication help decrease the incidence of side effects.[27]

- Tranexamic acid: Tranexamic acid (TXA) is an antifibrinolytic that reduces hemorrhage by blocking the breakdown of fibrin by plasmin. It is contraindicated in clients with active intravascular clotting and increases the risk of thromboembolic events. It may cause dizziness, visual disturbances, or seizures. It is typically administered intravenously in conjunction with a uterotonic.

- Intravenous fluids and blood products: Intravenous fluids and blood products are prescribed and administered to treat hypovolemia from blood loss.

Intrauterine Tamponade

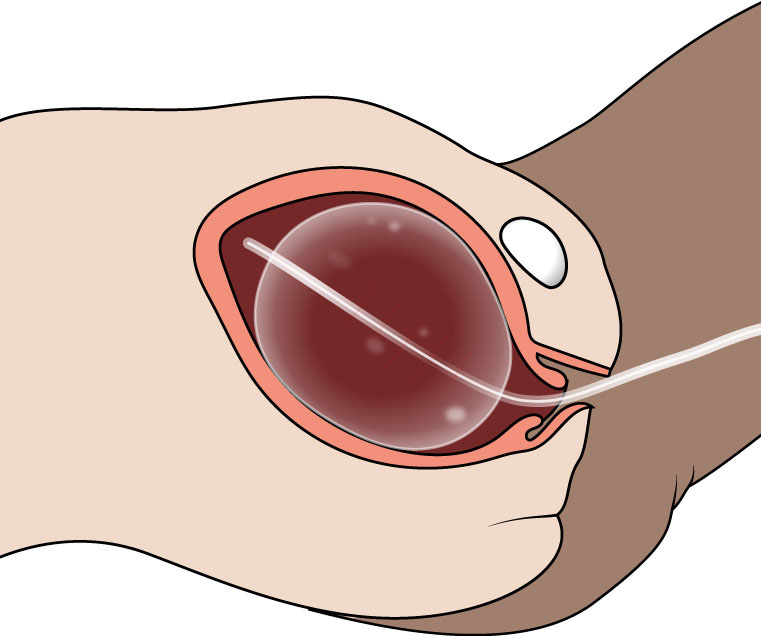

If PPH continues despite uterotonic administration and fundal massage, a health care provider may insert a uterine tamponade system. Two systems of intrauterine tamponade are available in the United States: the Bakri Balloon and the Jada System. The Bakri Balloon is placed inside the uterus, inflated by the health care provider, and compresses the inside of the uterus to stop the bleeding.[28] See Figure 11.12[29] for an illustration of a Bakri Balloon.

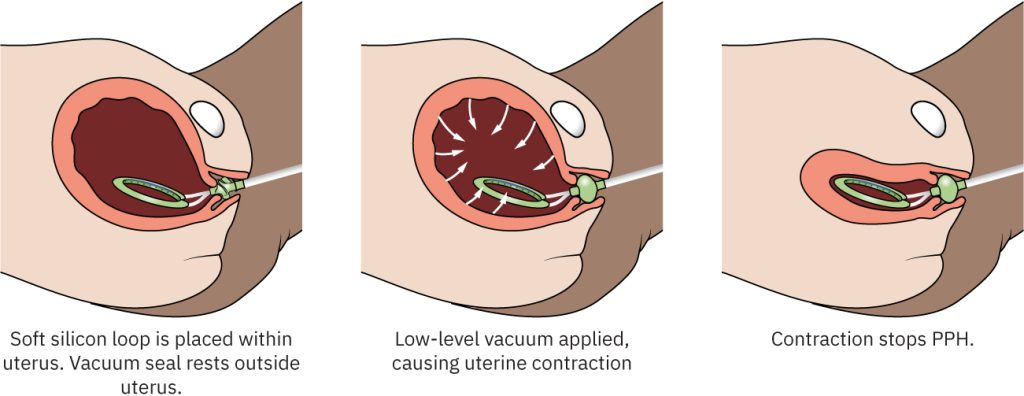

The Jada System is a device placed inside the uterus by a health care provider and uses an intrauterine vacuum to contract the uterus around the device to stop the bleeding. See Figure 11.13[30] for an illustration of the Jada System.[31]

If neither the Bakri Balloon nor Jada System are available, the health care provider may pack the uterus with gauze.[32]

Hysterectomy

If all interventions attempted to control PPH have failed, a hysterectomy is performed. The uterus is removed, and the blood vessels feeding the uterus are tied off and cauterized. Risk of emergency surgical complications include infection, further blood loss, bladder and ureteral injuries, and bowel damage. The postpartum post-hysterectomy client typically requires a great deal of emotional support from the nurse after this unexpected emergency surgery results in sterilization.[33]

Read additional information about postpartum hemorrhage in the “Hemorrhage” section of the “High-Risk Perinatal Client Care” chapter.

Postpartum Depression

During the first few days of the postpartum period, there is typically a feeling of well-being and heightened joy by the birth of the newborn. However, up to 50-70% of women may experience episodes of tearfulness, rapid mood swings, fatigue, and sadness commonly called the baby blues. The causes of the baby blues are unknown but are thought to be related to rapid changes in hormone levels, pain, lack of sleep, and feeling overwhelmed with the responsibilities of new parenthood. The baby blues are temporary and typically resolve within a couple of weeks. They do not affect the client’s ability to function or care for herself or her newborn. Nurses encourage clients to recover from the baby blues with self-care activities such as sleeping when the baby is sleeping, eating nutritious food, going for a walk, accepting help from others, and not worrying about completing household chores.[34],[35],[36]

Unlike the baby blues, postpartum depression (PPD) has more severe symptoms that impair the mother’s functioning in daily life. According to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 5th edition TR (DSM-5-TR), postpartum depression is diagnosed as a “Major Depressive Episode with Peripartum Onset” if mood symptoms begin during pregnancy or within the first four weeks after childbirth. It is estimated that about 7% of women will experience a major depressive episode between childbirth and 12 months postpartum. Mood symptoms occur nearly every day that impair functioning and include five or more of the following[37]:

- Depressed mood most of the day

- Diminished interest or pleasure in almost all daily activities

- Significant, unintentional weight gain or weight loss, or decreased or increased appetite

- Insomnia (difficulty falling asleep or staying asleep) or hypersomnia (excessive sleeping)

- Fatigue or loss of energy

- Psychomotor agitation or retardation

- Feelings of worthlessness or inappropriate guilt

- Diminished ability to concentrate or make decisions

- Recurrent thoughts of death or suicide

If left untreated, PPD affects the mother’s ability to care for her infant and establish a secure attachment, which can result in long-term developmental issues and/or behavioral problems. Clients suspected of having postpartum depression require prompt referral to a health care provider for evaluation and treatment.[38] Although rare, women with peripartum-onset major depression may develop psychosis. Postpartum psychosis is a psychiatric emergency with risk for potential suicide and infanticide. Clients may experience command hallucinations to kill the infant or delusions that the infant is possessed, creating significant safety concerns for the well-being of the infant. Once a woman has had a postpartum episode with psychotic features, the risk of recurrence with subsequent deliveries is between 30-50%.[39]

Read more information about the baby blues and postpartum depression from the March of Dimes: Baby Blues After Pregnancy.

Assessment

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG), the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP), and the American Academy of Family Medicine (AAFP) recommend screening every postpartum client for postpartum depression using the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS). The EPDS is a ten-item questionnaire that can be completed by clients within a few minutes. A score greater or equal to 13 is associated with an increased risk of developing PPD and indicates the need for further evaluation. View the EDPS screening tool in the following box.

View a PDF of the Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS).

Treatment

PPD is treated with a combination of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and antidepressant medications. The ACOG recommends selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors (SNRIs), and tricyclic antidepressants (TCA) for medical treatment of PPD. The goal of treatment is resolution of the symptoms of depression with an improvement of 50% on the EPDS screening tool. Once an effective dose is reached to resolve symptoms, continued treatment is recommended for at least 6 to 12 months to prevent relapse of symptoms. Nurses teach clients taking SSRIs or SNRIs to not abruptly stop taking these medications but to progressively taper off them to avoid symptoms such as gastrointestinal upset, agitation, anxiety, headache, dizziness, fatigue, sleep disruption, tremors, myalgias, and electric-like shocks.[40]

If a client with PPD is breastfeeding, the risk of transmitting SSRI in breastmilk is typically low. However, if a client is concerned about their infant being exposed to medication, or if CBT and antidepressant medications do not successfully resolve depression symptoms, an alternative treatment is transcranial magnetic stimulation. Transcranial magnetic stimulation is a noninvasive procedure that uses magnetic fields to stimulate nerve cells in a targeted area of the brain to improve symptoms of depression. This procedure is generally safe and well-tolerated.[41]

Read more information about antidepressant medications in the “Psychotropic Medications” section of the “Mental Health Conditions” chapter.

Read more information about cognitive behavioral therapy in the “Psychotherapy” section of the “Mental Health Conditions” chapter.

Read more information about transcranial magnetic stimulation in the “General Treatments for Mental Health Conditions” section of the “Mental Health Conditions” chapter.

- Cleveland Clinic. (2023). SIRS (Systemic inflammatory response syndrome). https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/25132-sirs-systemic-inflammatory-response-syndrome ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2023). SIRS (Systemic inflammatory response syndrome). https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/25132-sirs-systemic-inflammatory-response-syndrome ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “09662f906e890af8baee459df5941b2053958682” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Federspiel, J. J., Eke, A. C., & Eppes, C. S. (2023). Postpartum hemorrhage protocols and benchmarks: Improving care through standardization. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology Maternal Fetal Medicine, 5(2S), 100740. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9941009/ ↵

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2017). Practice Bulletin No. 183: Postpartum hemorrhage. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 130(4), e168-e186. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000002351 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Federspiel, J. J., Eke, A. C., & Eppes, C. S. (2023). Postpartum hemorrhage protocols and benchmarks: Improving care through standardization. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology Maternal Fetal Medicine, 5(2S), 100740. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9941009/ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Federspiel, J. J., Eke, A. C., & Eppes, C. S. (2023). Postpartum hemorrhage protocols and benchmarks: Improving care through standardization. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology Maternal Fetal Medicine, 5(2S), 100740. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9941009/ ↵

- Federspiel, J. J., Eke, A. C., & Eppes, C. S. (2023). Postpartum hemorrhage protocols and benchmarks: Improving care through standardization. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology Maternal Fetal Medicine, 5(2S), 100740. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9941009/ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Federspiel, J. J., Eke, A. C., & Eppes, C. S. (2023). Postpartum hemorrhage protocols and benchmarks: Improving care through standardization. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology Maternal Fetal Medicine, 5(2S), 100740. https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC9941009/ ↵

- California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. (2023). OB hemorrhage Toolkit V3 - Appendix B: Obstetric hemorrhage care guidelines: Checklist format. https://www.cmqcc.org/resource/ob-hemorrhage-toolkit-v30-appendix-b-obstetric-hemorrhage-care-guidelines-checklist-format ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Side_View_of_Postpartum_Uterine_Massage_with_Internal_Anatomy” by Valerie Henry is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Healthcare Simulation South Carolina. (2013, March 28). Uterine massage technique [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MEt2IQzia6E ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- DailyMed. (2023). Oxytocin. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=c7fd585a-99b7-4309-b003-a6cbef05372c&audience=consumer ↵

- DailyMed. (2024). Misoprostol. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=21e20753-4a67-ce4e-e063-6394a90aa598 ↵

- DailyMed. (2024). Methylergonovine. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=8bccff44-2a39-400a-b8a4-2eb5249fdbc8&audience=consumer ↵

- DailyMed. (2023). Carboprost. https://dailymed.nlm.nih.gov/dailymed/drugInfo.cfm?setid=ce9f0ea6-69f9-6b68-2811-3b51e34acea6&audience=consume ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “7d7d1022182d8a4f9f67d5636e9612c7c948ae9e” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “fdaa4ed1f53d02045cee0e6c9413c21e3dd763d1” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Carlson, K., Mughal, S., Azhar, Y., et al. (2024). Postpartum depression. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519070/ ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- Carlson, K., Mughal, S., Azhar, Y., et al. (2024). Postpartum depression. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519070/ ↵

- American Psychiatric Association. (2022). Desk reference to the diagnostic criteria from DSM-5-TR (5th ed.). American Psychiatric Association Publishing. ↵

- Carlson, K., Mughal, S., Azhar, Y., et al. (2024). Postpartum depression. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519070/ ↵

- Carlson, K., Mughal, S., Azhar, Y., et al. (2024). Postpartum depression. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519070/ ↵

A life-threatening condition where the body's immune system overreacts to an infection, causing widespread inflammation and potential organ damage.

A serious condition that occurs when the body has an exaggerated defense response to a harmful stressor, resulting in severe inflammation throughout the body.

A life-threatening decrease in blood pressure (systolic pressure <90 mm Hg) that prevents cells and other organs from receiving enough oxygen and nutrients, causing multi-organ failure and death.

Inflammation of the inner lining of the uterus (endometrium), often caused by infection. It can occur after childbirth, miscarriage.

Inflammation of breast tissue, often due to infection, commonly occurring during breastfeeding.

A healthcare professional who specializes in providing support and guidance to breastfeeding mothers.

Total blood loss greater than or equal to 1,000 mL or blood loss and signs or symptoms of hypovolemia within 24 hours after birth.

The uterus not adequately returning to its prepregnant size.

A process of weighing and measuring the amount of blood lost during childbirth and the immediate postpartum period.

Involves applying firm pressure to the fundus to induce a uterine contraction and to stop the blood from pumping out of the spiral arteries. The goal is to cause the uterus to contract into the size of a small, hard ball.

Top of the uterus.

A surgical procedure to remove uterine fibroids while preserving the uterus. It is often recommended for women who wish to maintain fertility.

Episodes of tearfulness, rapid mood swings, fatigue, and sadness occurring in the postpartum period.

A mood disorder that can affect new mothers, characterized by feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and exhaustion. It typically occurs within the first few months after childbirth.

Sleeping excessively.

A psychiatric emergency with risk for potential suicide and infanticide.