10.8 Complications and Medical Interventions During the Second Stage of Labor

During the second stage of labor, the client is working very hard to push, and the fetus is working hard to be born. The fetus may have difficulty engaging in the pelvis, causing failure to descend, or the client may become fatigued from pushing. The nurse monitors for signs of fetal and maternal distress during a prolonged second stage of labor.[1]

Complications During the Second State of Labor

Prolonged Second Stage

Prolonged second stage labor is defined as a second stage labor lasting longer than three hours for a nulliparous person and longer than two hours for a multiparous person. Risk factors for prolonged second stage are use of epidural anesthesia, persistent occiput posterior position, and fetal head circumference or birth weight above the 90th percentile. Complications resulting from prolonged second stage include chorioamnionitis, postpartum hemorrhage, extended perineal lacerations, and shoulder dystocia. Prolonged second stage of labor can be caused by fetal failure to descend or by maternal labor fatigue. Medical interventions for a prolonged second stage of labor include operative vaginal delivery (i.e., using forceps or a vacuum extractor to expedite a vaginal birth) or performing a cesarean section.[2]

Failure to Descend

During second stage labor, the fetal presenting part descends past the cervix, into the vagina, and out past the perineum. Failure to descend is defined as lack of change in the fetal station for at least two hours. Failure to descend is often caused by fetal malpositioning, especially occiput posterior position.[3]

Labor Fatigue

The second stage of labor takes a great deal of energy and effort, and laboring clients can become fatigued. If the client can no longer continue pushing, it is called labor fatigue. As previously discussed, one of the “P’s of labor” is power. Power can become deficient due to labor fatigue and result in second stage dystocia. The nurse can support the client and encourage interventions to help decrease fatigue, such as waiting until the peak of the contraction to bear down and push, drinking fluids and eating healthy snacks during labor to replenish calories, and allowing the fetus to descend or “labor down” before pushing.[4]

Abnormal FHR

During the second stage, the fetal head molds to fit through the maternal pelvis. The nurse closely monitors FHR during the second stage of labor as the fetus descends. The compression on the fetal head and molding that occur during the second stage of labor can cause FHR decelerations, ranging from normal Category I early decelerations (e.g., FHR decelerations mirror the contractions) to nonreassuring Category II or abnormal Category III FHR. For example, abnormal late decelerations (e.g., decelerations that start during a uterine contraction and continue after completion of the contraction) may occur due to uteroplacental insufficiency, or abnormal fetal bradycardia (e.g., slow FHR lasting longer than two minutes) may occur due to fetal hypoxia. If abnormal FHR occurs, medical interventions are performed by the health care provider to expedite birth and prevent fetal acidosis, such as performing an episiotomy, using forceps or a vacuum extractor, or performing an emergency cesarean birth.[5]

Shoulder Dystocia

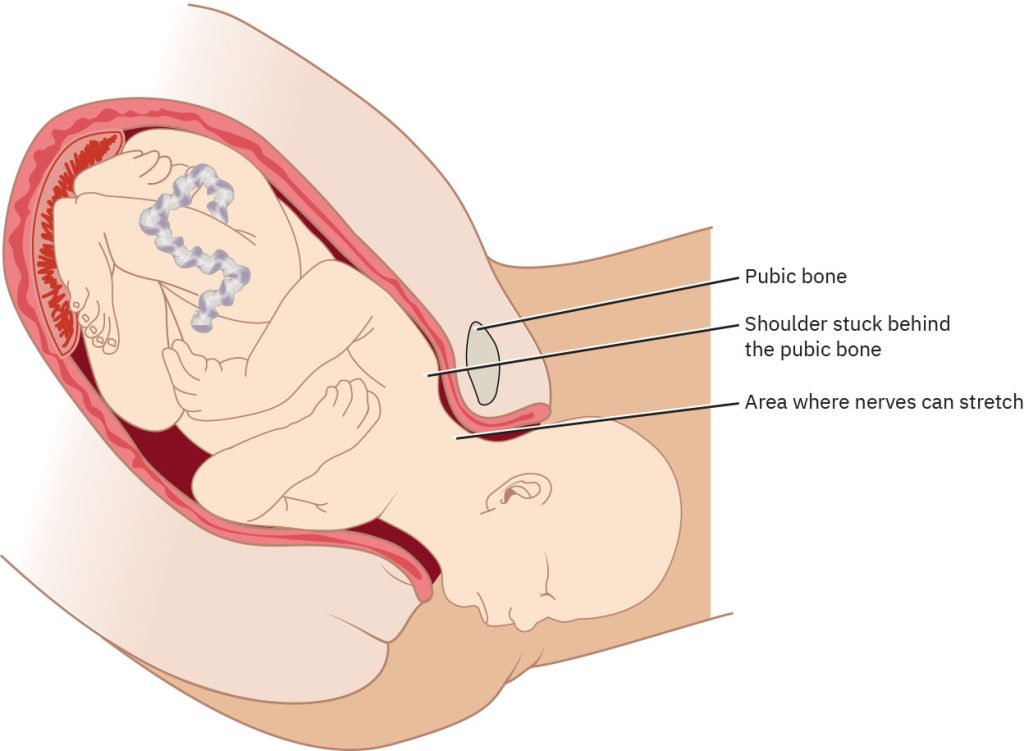

Shoulder dystocia is when the fetal shoulder gets stuck behind the maternal symphysis pubis or sacral promontory, preventing the delivery of the fetus. It is characterized by the failure to deliver the fetal shoulders using typical gentle downward traction and requires additional obstetric maneuvers to successfully deliver the newborn. It is considered an obstetrical emergency and occurs in less than three percent of births. See Figure 10.61[6] for an illustration of shoulder dystocia. There are no warning signs of shoulder dystocia and no way to prevent this condition, but risk factors include history of previous shoulder dystocia, a fetus that is large for gestational age (8 pounds, 13 ounces or larger), maternal obesity, excessive weight gain during pregnancy, multiparity, and diabetes. However, 50 percent of shoulder dystocia occurs in normal-weight fetuses and clients who do not have diabetes, so health care providers and nurses should always be prepared for shoulder dystocia. Complications of shoulder dystocia include increased risk of postpartum hemorrhage, perineal lacerations, fetal brachial plexus injuries, fractures of the fetal clavicle and humerus, and fetal hypoxia.[7],[8]

Rapid interventions are required when shoulder dystocia occurs. The nurse positions the client to help the provider perform maneuvers. The first maneuver is McRoberts maneuver, the process of flexing the laboring client’s legs until their thighs touch their abdomen. Posterolateral suprapubic pressure is then provided to attempt to dislodge the fetal shoulder from underneath the pubic bone. The nurse needs to be positioned well above the woman to apply the correct pressure, so a stool or chair at the bedside is needed to apply downward, lateral pressure with one or both hands toward the fetal-facing side. See Figure 10.62[9] for an illustration of posterolateral suprapubic pressure. If this maneuver is not successful, the health care provider may perform an episiotomy and attempt to deliver the posterior arm or attempt to turn the fetal shoulders. If these maneuvers are not successful, the nurse assists in turning the client into a hands-and-knees position to facilitate delivery.[10]

Medical Interventions During the Second Stage of Labor

Operative Vaginal Delivery

The use of forceps or vacuum-assisted birth is called operative vaginal delivery.

Obstetric Forceps

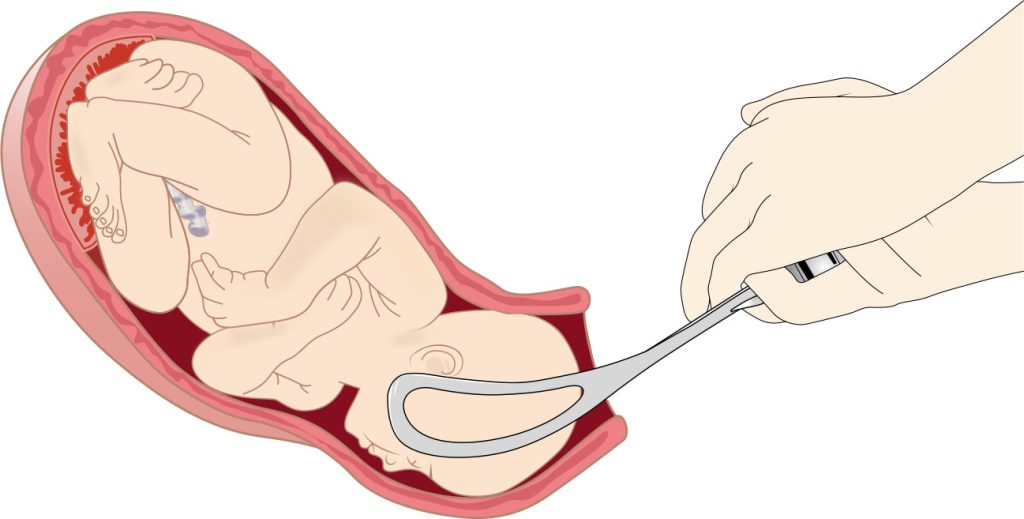

Metal instruments that are used to rotate the fetal head or otherwise assist in the vaginal delivery of the fetus are called obstetric forceps. Forceps are used as an alternative to performing a cesarean section. They may be used for a prolonged second stage of labor due to maternal fatigue, when the birth must urgently occur due to abnormal FHR, or for delivery of the fetal head after a breech presentation. Obstetric forceps are designed to fit the fetal head and cradle the fetal skull to apply traction, rotation, flexion, and extension, as seen in Figure 10.63.[11] Forceps birth is attempted only if the cervix is completely dilated, the membranes are ruptured, the fetal head is low in the pelvis, and the provider does not suspect cephalopelvic disproportion. Potential maternal complications of obstetric forceps are lacerations of the vagina and cervix, pelvic hematomas, urethral and bladder injury, rupture of the uterus, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Fetal complications include facial lacerations and nerve damage, cephalohematomas, skull fractures, intracranial hemorrhage, and seizures.[12]

When the health care provider makes the decision to use forceps to deliver the fetus and obtains informed consent from the client, the nurse performs several actions. If the client has an epidural, the nurse calls the anesthesia provider to ensure adequate pain relief during the procedure and notifies the neonatal team to be in the room in case of neonatal complications. The nurse ensures the client’s bladder is emptied and then assists them into the lithotomy position. During the procedure, the nurse continues to monitor uterine contractions and FHR for abnormal responses.[13]

Vacuum-Assisted Birth

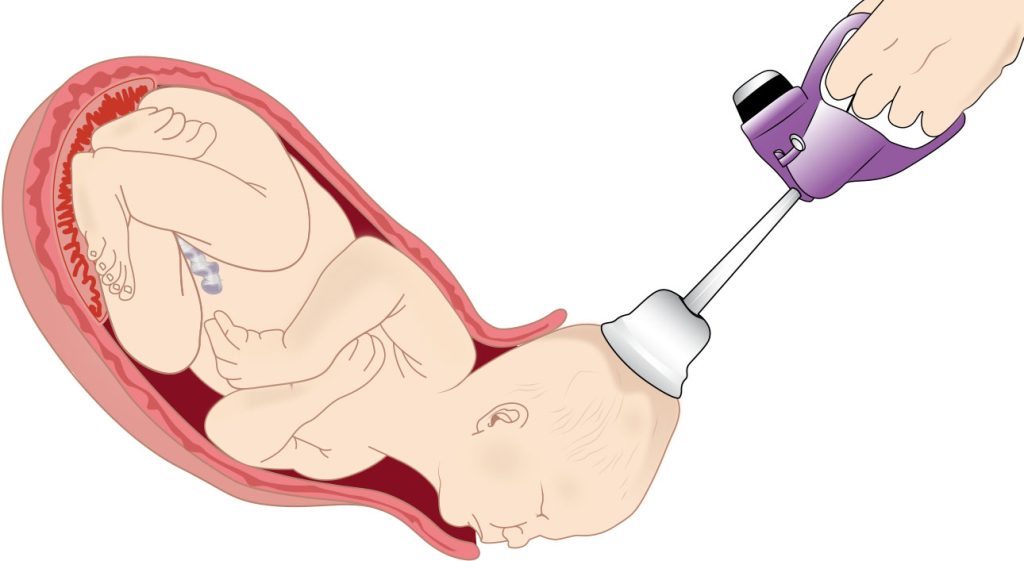

A vacuum-assisted birth uses a suction cup and vacuum device to apply controlled suction to the fetal head, helping guide them through the birth canal. This procedure is typically employed when there is a need for additional assistance during the pushing stage of labor and is safer than forceps delivery. See Figure 10.64[14] for an illustration of a vacuum extractor. After the vacuum is applied to the fetal head, suction is increased during contractions and pushing, and traction is performed by the health care provider. The suction pressure is decreased between contractions. The role of the nurse is to monitor uterine contractions and FHR during the procedure and assist with adjusting the suction pressure. Indications for a vacuum-assisted delivery are the same as for forceps-assisted delivery. Contraindications to the use of the vacuum include face or breech presentation, cephalopelvic disproportion, fetal head anomaly, preterm fetus, or fetal bleeding risk. Complications include neonatal injury, such as superficial scalp markings, retinal hemorrhage, cephalohematoma, subgaleal hematoma (bleeding between the skull and the scalp), and intracranial hemorrhage. The vacuum can also cause maternal perineal and vaginal lacerations. Nursing actions are similar as those for a forceps delivery.[15]

Episiotomy

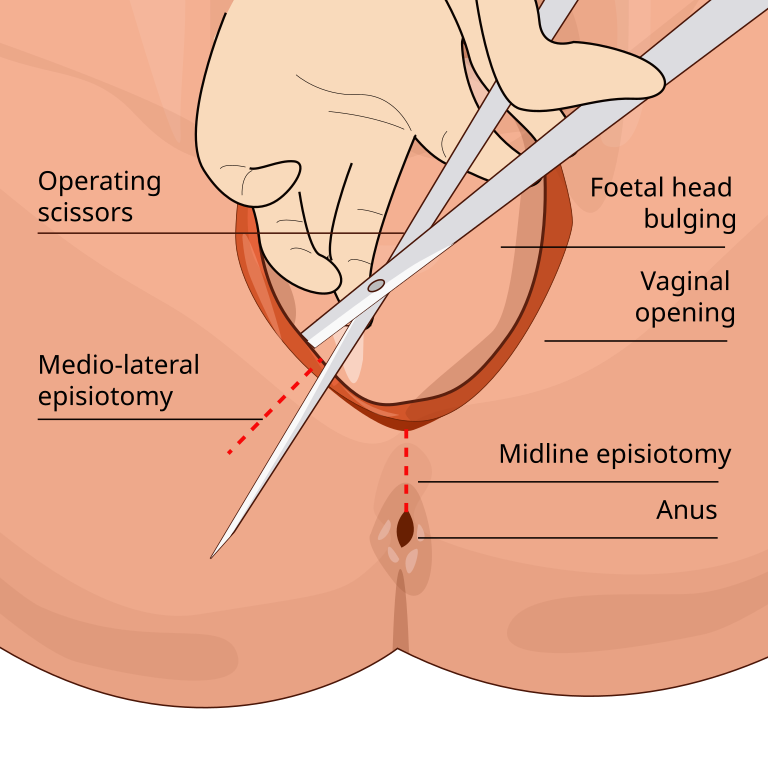

An episiotomy may be performed by the health care provider during the second stage of labor to quickly facilitate vaginal delivery or to prevent large, irregular tears of the vaginal wall. Episiotomies may be performed for shoulder dystocia, nonreassuring FHR patterns, or a forceps or vacuum-assisted delivery. During an episiotomy, the health care provider makes a small incision to enlarge the vaginal opening.[16] See Figure 10.65[17] for an illustration of an episiotomy.

Research is mixed about potential ways to avoid episiotomies. One method used for avoiding an episiotomy is perineal tissue massage (massaging the area between the vaginal opening and anus) in the weeks leading up to delivery or during the second stage of labor. Another technique to reduce tearing is to apply a warm compress to the perineum during the second stage of labor to make the tissue more flexible.[18]

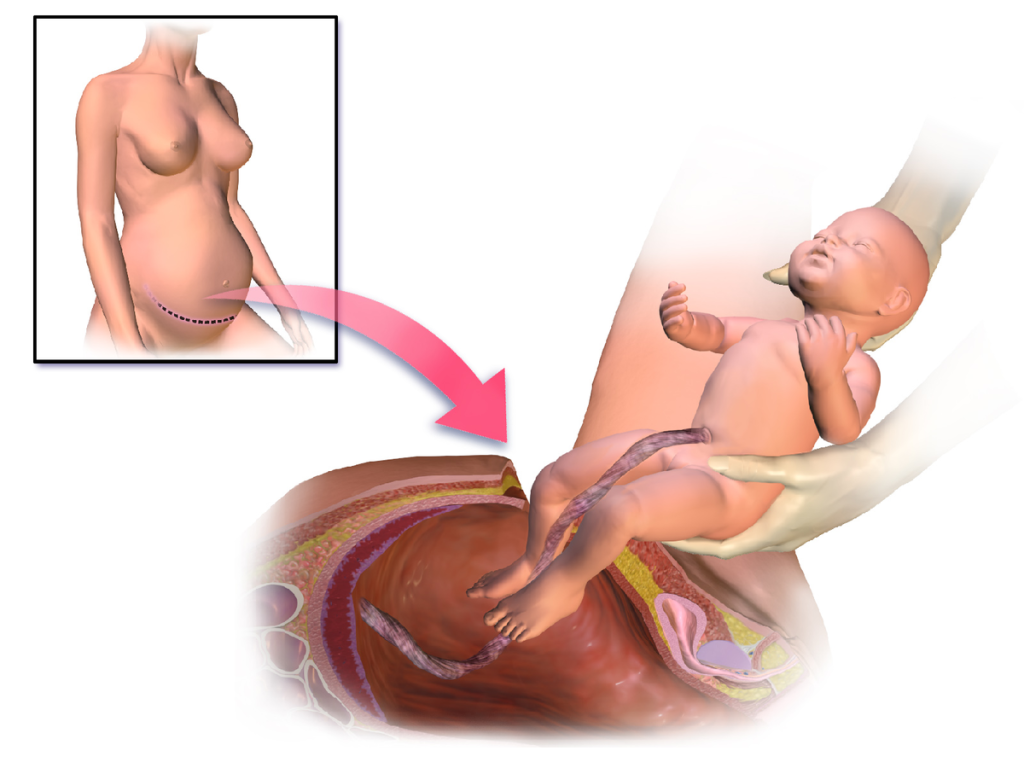

Cesarean Section

Cesarean section (C-section) is a surgical procedure performed to deliver a fetus through incisions made in the mother’s abdomen and uterus when a vaginal birth poses risks to the mother or fetus or when complications occur during labor. See Figure 10.66[19] for an illustration of a C-section.

C-sections can be planned or emergent. Common causes for planned C-sections include multiple gestation, large-for-gestational age fetus, active herpes simplex lesions, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, malpresentation of the fetus, placenta previa, previous C-section, and complications that arise during pregnancy. Unplanned C-sections can be caused by dystocia, fetal distress, abnormal fetal positioning, placental issues, or other complications that occur during labor. While cesarean deliveries are generally considered safe, they are major surgeries that carry risks such as infection, bleeding, thromboembolism, paralytic ileus, atelectasis, anesthesia complications, and longer recovery times compared to vaginal births.[20],[21] C-sections also pose added risks for the newborn, which may include inadvertent preterm birth, transient tachypnea caused by delayed absorption of lung fluid, and inadvertent surgical injury, such as laceration.[22]

Typically, regional anesthesia is used during planned C-sections, such as a spinal block or epidural block, to numb the lower body and allow the client to remain awake during delivery. General anesthesia is used for emergency C-sections when there is urgent need to quickly deliver the fetus. Concerns for using general anesthesia include potential maternal aspiration of gastric contents and exposure of the fetus to general anesthetic.

Two types of incisions may be used for C-sections. A low transverse incision is the most common type of cesarean incision that is made horizontally just above the pubic hairline. It is considered to be cosmetically favorable and generally associated with less pain and a lower risk of complications. This type of incision can make it possible for future vaginal births. A second type of incision is called a vertical incision, also called a classical incision. This incision is made vertically along the midline of the abdomen, usually starting just below the umbilicus and extending down to the pubic bone. It is typically only used during emergency C-sections due to a higher risk of complications, such as uterine rupture in subsequent pregnancies and bladder injury.

The nurse’s role in preparing a client for a planned C-section is to answer questions, provide support to the client and their partner, and complete a preoperative checklist. See a typical preoperative checklist in the following box.

Preoperative Checklist for Scheduled Cesarean Birth[23]

- Verify client name, date of birth, medication allergies, and reason for cesarean birth.

- Ensure informed consent forms are signed.

- Document pregnancy complications and medical conditions.

- Assess vital signs and FHR.

- Initiate IV access and administer IV fluid bolus per provider orders prior to regional anesthesia.

- Shave operative site.

- Place sequential compression devices on legs.

- Apply a grounding pad.

- Insert indwelling urinary catheter.

- Prep abdomen with antiseptic.

- Assess FHR prior to start of procedure.

- Complete the surgical time-out procedure.

The nurse encourages the client’s partner to be present in the operating room and recovery room to promote bonding and attachment.

View a supplementary video[24] of cesarean birth at Live Birth: C-Section Surgery.

Note: This video contains medical situations and nudity. If you’re in a public place, consider watching it privately.

Vaginal Birth After Cesarean

Clients who have had a previous C-section may have the option in subsequent births to attempt a trial of labor and vaginal delivery called a vaginal birth after cesarean (VBAC). Several factors determine the safety of attempting a VBAC, such as the previous type of C-section incision, number of previous C-section births, interval between pregnancies, and history of uterine rupture. A previous low transverse incision makes a VBAC more likely, whereas a vertical incision cuts through the uterine muscles that strongly contract during labor and may cause uterine rupture. The majority of women with one low transverse uterine incision from a previous cesarean birth have successful VBAC. However, women who had a previous C-section for dystocia are less likely to have a successful VBAC.[25],[26]

Recommendations from the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) related to VBAC include the following[27]:

- No more than two previous low transverse uterine incisions.

- No other uterine scars (e.g., removal of fibroid tumors) or a previous uterine rupture.

- A pelvis that is clinically adequate for the estimated fetal size.

- Immediate availability of a physician during active labor if an emergency cesarean is needed.

- Availability of anesthesia and personnel to perform an emergency cesarean.

- Epidural analgesia and anesthesia may be used.

- Labor induction and labor augmentation with oxytocin may be done, but misoprostol should not be used for cervical ripening.

- Electronic fetal monitoring is recommended due to the risk of uterine rupture. The most common sign of uterine rupture is an abnormality of the fetal heart rate tracing, which is seen in approximately 70% of cases of uterine rupture.

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “1551edfde22985cf618ce7500e59ee2af9802bc0” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/19-7-obstetrical-emergencies ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Sung, S., Mikes, B. A., & Mahdy, H. (2024). Cesarean section. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546707/ ↵

- “1a2138bb84db4e6cc8205fadcd1bc84f1a8b76e7” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/19-7-obstetrical-emergencies ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “55a156c1e4c111d0f27502266e0d938362be5218” by Rice University/OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/19-5-interventions-during-birth ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “8f9abeea63ef4309c35e61ea67ec2892a8a12953” by Rice University/Open Stax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/19-5-interventions-during-birth ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Epiosotomy_svg_hariadhi” by Hariadhi is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Blausen_0223_CesareanDelivery” by Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014” is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Sung, S., Mikes, B. A., & Mahdy, H. (2024). Cesarean section. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546707/ ↵

- Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research. (2022). C-section. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/c-section/about/pac-20393655 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- BabyCenter. (n.d.). Live birth: C-section surgery [Video]. JW Player. All rights reserved. https://www.babycenter.com/pregnancy/your-body/live-birth-c-section-surgery_3656510 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal-newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Habak, P. J., & Kole, M. (2023). Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507844/ ↵

- Habak, P. J., & Kole, M. (2023). Vaginal birth after cesarean delivery. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK507844/ ↵

A second stage labor lasting longer than three hours for a nulliparous person and longer than two hours for a multiparous person.

Defined as lack of change in the fetal station for at least two hours.

If the client can no longer continue pushing.

The shoulder of the newborn becomes stuck on the mother’s pubic symphysis.

The process of flexing the laboring client’s legs until their thighs touch their abdomen.

Use of forceps or vacuum-assisted birth.

Metal instruments that are used to rotate the fetal head or otherwise assist in the vaginal delivery of the fetus.

Bleeding between the skull and the scalp.

Performed by the health care provider during the second stage of labor to quickly facilitate vaginal delivery or to prevent large, irregular tears of the vaginal wall.

A surgical procedure performed to deliver a fetus through incisions made in the mother's abdomen and uterus when a vaginal birth poses risks to the mother or fetus or when complications occur during labor.

The most common type of cesarean incision that is made horizontally just above the pubic hairline. It is considered to be cosmetically favorable and generally associated with less pain and a lower risk of complications.

This incision is made vertically along the midline of the abdomen, usually starting just below the umbilicus and extending down to the pubic bone.

Clients who have had a previous C-section may have the option in subsequent births to attempt a trial of labor and vaginal delivery.