9.9 Second Trimester Prenatal Care

Second trimester prenatal care occurs between gestational Week 14 and 27 weeks and 6 days.

Interval History

Interval history is obtained at each visit in the second trimester. The nurse asks the client if they have experienced any of the following symptoms since the previous prenatal visit:

- Vaginal discharge, bleeding, or leaking of fluid

- Persistent vomiting

- Epigastric or abdominal pain

- Pelvic pressure or uterine cramping

- Braxton-Hicks contractions

- Back pain or dysuria

- Dizziness or syncope

- Headache

- Edema in the legs, hands, or face

- Visual disturbances

- Decrease in fetal movements

If the client responds “Yes” to any of the symptoms, the nurse notifies the health care provider for additional evaluation because these symptoms may indicate a complication of pregnancy is occuring. See Table 9.9 for complications of pregnancy associated with these symptoms during the second trimester of pregnancy.

Table 9.9. Signs of Complications During the Second Trimester of Pregnancy

| Symptom | Possible Complication |

|---|---|

| Persistent vomiting | Hyperemesis gravidarum, dehydration |

| Dysuria, intermittent back pain | UTI |

| Pelvic pressure or lower abdominal cramping | Cervical insufficiency or preterm labor |

| Vaginal bleeding | Miscarriage, placenta previa, or placental abruption |

| Change in fetal movement pattern | Fetal stress or intrauterine fetal demise |

| Temperature >38.3° C (101° F) | Infection |

| Persistent abdominal pain or epigastric pain | Cholelithiasis, liver disease, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), preeclampsia, or HELLP syndrome (Hemolysis of red blood cells, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count causing increased bleeding) |

| Frequent dizziness | Anemia, dehydration, infection, or heart disease |

| Leaking of fluid from the vagina | Vaginitis or premature rupture of membranes (PROM) |

| Headache | Hypertension |

| Edema | Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy |

| Visual disturbances | Hypertensive disorders of pregnancy |

Objective Data

In the second trimester, follow-up prenatal visits are similar to first trimester follow-up visits and include data collection such as client weight, blood pressure, urine dipstick testing, fundal height, fetal heart rate, and fetal movement.[1]

Inadequate weight gain may indicate the fetus is not growing as expected whereas a sudden, rapid weight gain may indicate excessive fluid retention. Elevated blood pressure is reported to the health care provider. If the client’s BP is 140/90 mm Hg or higher prior to 20 weeks of gestation, this indicates preexisting hypertension. An elevated BP and/or proteinuria after 20 weeks of gestation indicates possible preeclampsia. A positive nitrate indicates a possible urinary tract infection that requires further evaluation by the health care provider.[2]

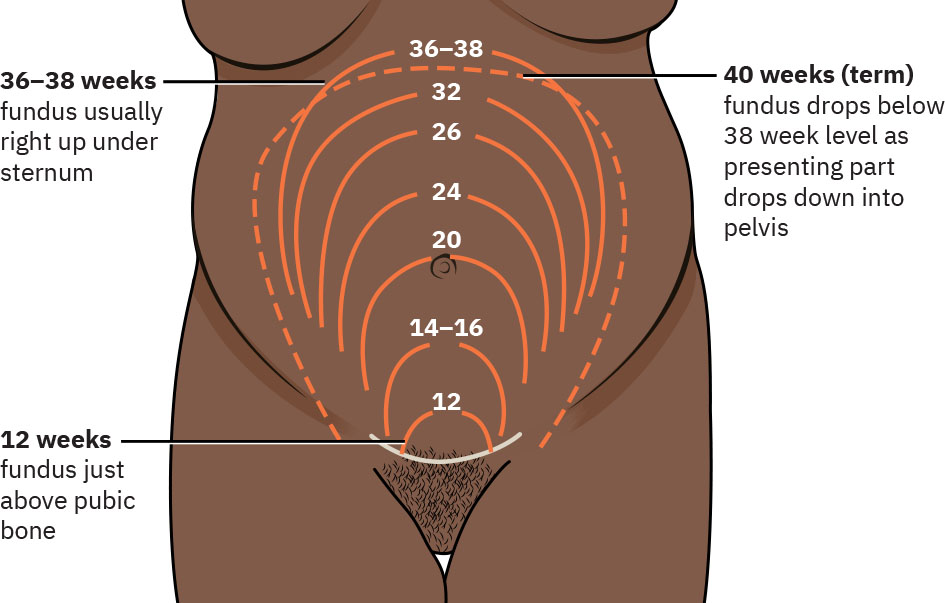

From 16 to 18 weeks until 36 weeks, the fundal height is measured in centimeters, and this measurement is approximately equal to the gestational age of the fetus in weeks. The fundal height is measured from the symphysis pubis to the top of the uterus (fundus). During the second trimester, the uterine fundus is expected to be halfway between the symphysis and the umbilicus at 16 weeks, and at or just below the umbilicus at 20 weeks of gestation. Uterine tenderness on palpation is noted, which could indicate infection. See Figure 9.19[3] for an illustration of fundal height. If there is a discrepancy between fundal height and weeks of gestation, additional evaluation is necessary. Several factors can affect fundal height, such as an incorrect EDD, the number of fetuses present, fetal growth, the amount of amniotic fluid, presence of fibroids, or gestational trophoblastic disease (hydatidiform mole).[4]

The fetal heart rate should be between 110 and 160 bpm. The location of the fetal heart sounds also provides information that helps determine the fetal presentation. For example, a fetal heartbeat that is heard best in a lower quadrant of the maternal abdomen suggests the fetal head is down, but if it is heard best in the upper quadrant of the abdomen, this suggests that the fetus is in a breech presentation.[5]

Fetal movement (also called quickening) is usually first noticed by the mother at 16 to 24 weeks of gestation, and then fetal movements gradually increase in frequency and strength and indicate the fetus is physically healthy. If the pregnancy continues to be normal, the follow-up visits are every four weeks in the second trimester.[6]

Diagnostic Testing and Laboratory Tests

Comprehensive Ultrasound

A complete obstetric ultrasound (US) in the second trimester is performed by a trained sonographer at 16 to 20 weeks of gestation to assess the following[7]:

- Determine the location of the placenta

- Measure the fetus to determine the fetal weight and confirm the EDD

- Measure the amniotic fluid

- Observe fetal movement

- Auscultate the fetal heart rate

- Evaluate fetal anatomy, including external genitalia

- Determine the length of the cervix

Laboratory Tests and Screening

Laboratory tests routinely performed in the second trimester include the following[8]:

- Complete blood count (CBC) or hemoglobin & hematocrit (H&H)

- Gestational diabetes screens (such as 1-hour glucose challenge test and 3-hour glucose tolerance test)

- Blood type, Rh, and antibody screen on pregnant women who are Rh negative

A complete blood count (CBC) or hemoglobin and hematocrit (H&H) is done at least once a trimester to detect anemia. A client whose hemoglobin drops below 10.5 g/dL during the second trimester of pregnancy because of iron-deficiency anemia is treated with iron supplements. A CBC also includes the RBC indices to help diagnose iron-deficiency anemia, and platelet counts are monitored for thrombocytopenia. A significant drop in the platelet count from the previously drawn CBC at the first prenatal visit or a platelet count less than 150,000 per microliter of blood is associated with liver damage and hypertensive disorders of pregnancy.[9]

All pregnant women are screened for gestational diabetes between 24 and 28 weeks of gestation unless they have preexisting diabetes mellitus or a confirmed diagnosis of gestational diabetes with the current pregnancy. The most commonly used diabetes screen is the one-hour glucose challenge test (GCT). The GCT does not require the client to be NPO before undergoing the test. The client is instructed to drink a glucose solution containing 50 grams of carbohydrate. One hour later the client’s blood glucose level is checked. If the glucose is elevated (>130 mg/dl serum or >140 mg/dl using a fingerstick or whole blood), the client is scheduled for a three-hour GTT (glucose tolerance test). The client is instructed to be NPO the night before and the morning of the test. Blood is drawn right before the client starts drinking a glucose solution containing 100 grams of carbohydrate, and at one, two, and three hours after the client finishes drinking the solution. If the client’s serum blood glucose level is elevated in any two out of the four blood draws, the client is diagnosed with gestational diabetes and referred to nutritional counseling. The client is also educated on the possible effects of gestational diabetes on the pregnancy outcome.[10]

Pregnant women who are Rh negative will have their blood type, Rh, and antibody screen repeated right before or at 28 weeks of gestation. If the client’s antibody screen is negative, the client receives antepartum Rho(D) immune globulin (RhoGAM). Antepartum RhoGAM is administered to prevent the client from producing antibodies against Rh-positive blood or Rh sensitization during the third trimester of pregnancy.[11]

Rho(D) Immune Globulin (RhoGAM)[12]

A person who is Rh negative carries antibodies against Rh-positive blood. During pregnancy, the placenta usually prevents the mixing of the pregnant woman’s and fetus’s blood. However, if episodes of placental bleeding occur at any point during the pregnancy, and during delivery, miscarriage, or abortion, fetal blood may mix with the pregnant woman’s blood, resulting in the production of antibodies, called Rh sensitization. Rho(D) immune globulin is administered at the time of a bleeding episode, miscarriage or abortion, at 28 weeks’ gestation, and after delivery to interrupt the Rh sensitization process.

- Generic Name: Rho(D) immune globulin

- Trade Name: RhoGAM, MicRhoGAM, WinRho SDF

- Classification: Immunoglobulin

- Dosage: 300 micrograms at 28 weeks of pregnancy and 50 micrograms after first trimester miscarriage or abortion

- Route: Administered intramuscularly (IM) or intravenously (IV)

- Indications: Prevention of Rh sensitization related to pregnancy in clients who are Rh negative and whose fetus is Rh positive

- Mechanism of Action: Prevents the body from producing antibodies that destroy Rh-positive blood cells

- Contraindications: Known allergy to any ingredient in Rho(D) immune globulin

- Side Effects: Pain and redness at the site if administered IM or slight elevation in temperature

- Adverse Reactions: Anaphylaxis and hemolytic reactions

- Health Teaching: Notify the health care provider if experiencing shortness of breath, headache, or muscle pain. Carry the card provided after the injection in a wallet for identification as an Rh-negative person

Other Screening and Diagnostic Tests

Additional second trimester prenatal testing is offered to all pregnant women regardless of the risk factors present and may be recommended if screenings performed during the first trimester came back abnormal. Other reasons for second trimester prenatal testing include the following[13]:

- Detecting congenital anomalies

- Evaluating the condition of the fetus if the pregnancy is high risk to allow for appropriate intervention

- Providing baseline information

Nurses have an important role in educating pregnant women and their partners about the prenatal tests that are offered or recommended so they can decide whether to have testing done. Screening and diagnostic tests available during the second trimester include the following:

- Quad marker screen

- Alpha-fetoprotein screening

- Amniocentesis

- Percutaneous blood sampling (PUBS)

- Umbilical Doppler study

- Fetoscopy

The results of the screenings and tests can help pregnant women and their families make decisions about continuing the pregnancy or preparing for the delivery of an infant who may have special needs or require additional medical care.

Quad Marker Screen

A quad marker screen measures the maternal serum levels of four pregnancy markers (alpha fetoprotein, hCG, unconjugated estriol, and inhibin-A), and a blood sample is drawn when the client is between 15 and 22 weeks of gestation. The quad marker screen is offered to all clients who are pregnant, but it is strongly encouraged when clients have risk factors for delivering a baby with chromosome abnormalities, such as when the client is older than 35 or the client has previously delivered a fetus or newborn with a neural tube defect. A positive result means that the developing fetus is at a higher risk for having Down syndrome, trisomy 18, or an open neural tube defect. A positive result does not mean the fetus will have these problems, but they have a higher risk. As a result, the health care provider may recommend additional testing, such as an amniocentesis or detailed fetal anatomy ultrasound. As in the first trimester, some clients choose not to have any of the integrated or marker screenings performed.[14]

Alpha-Fetoprotein

The alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) test is a blood test that screens for increased risk of neural tube defects and the congenital anomalies by measuring the level of alpha-fetoprotein in the pregnant woman’s blood. AFP is dispersed from fetal plasma into fetal urine and excreted into the amniotic sac. The AFP test is typically recommended between the 15th and 22nd weeks of pregnancy and can be measured from maternal blood or from amniotic fluid.[15]

Clients at higher risk include the following[16]:

- Family history of birth defects

- Maternal age 35 or older

- Mothers who use high-risk medications or illicit drugs while pregnant

- Mothers who have diabetes mellitus

If the AFP levels are low and abnormal levels of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) and estriol are also found, it may indicate the fetus is at higher risk for trisomy 21 (Down syndrome), trisomy 18 (Edwards syndrome), or another type of chromosomal abnormality. Elevated AFP results indicate increased risk of neural tube defects.

If the AFP test comes back abnormal, additional diagnostic testing is recommended. Less invasive diagnostic testing includes the following[17]:

- A second AFP test

- A multiple marker test (including testing for AFP, hCG, and estriol)

- High-definition ultrasound

An amniocentesis may be recommended if the additional testing results are still abnormal. Approximately 20 to 50 abnormal AFP tests result for every 1,000 pregnancy tests. Of those, only 1 in 16 to 1 in 33 results in a fetus with a neural tube defect or other chromosomal abnormality.[18]

Amniocentesis

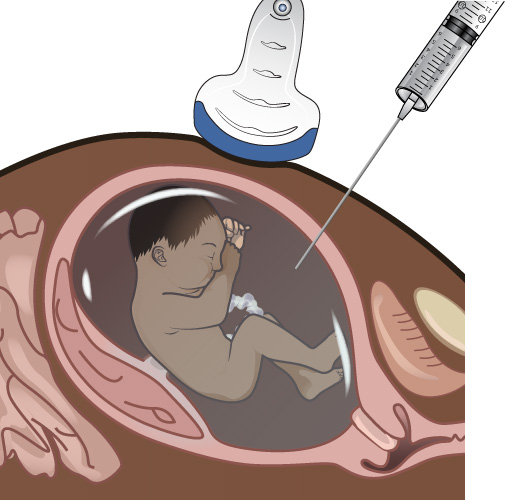

Amniocentesis may be performed to diagnose fetal genetic abnormalities between 15- and 20-weeks’ gestation because amniotic fluid volume is adequate and there are many viable fetal cells in the fluid. During an amniocentesis, a large-bore needle is inserted under ultrasound guidance into a pocket of amniotic fluid and fluid is withdrawn for analysis. See Figure 9.20[19] for an illustration of amniocentesis.[20]

Amniocentesis is beneficial but it is not without risks. Approximately 1 in 900 procedures result in an adverse event, which may include leaking of amniotic fluid; miscarriage; needle injury to the fetus; Rh sensitization; uterine infection; or transmission of infectious diseases such as HIV, hepatitis, or toxoplasmosis from the mother to the fetus.[21]

Percutaneous Umbilical Blood Sampling

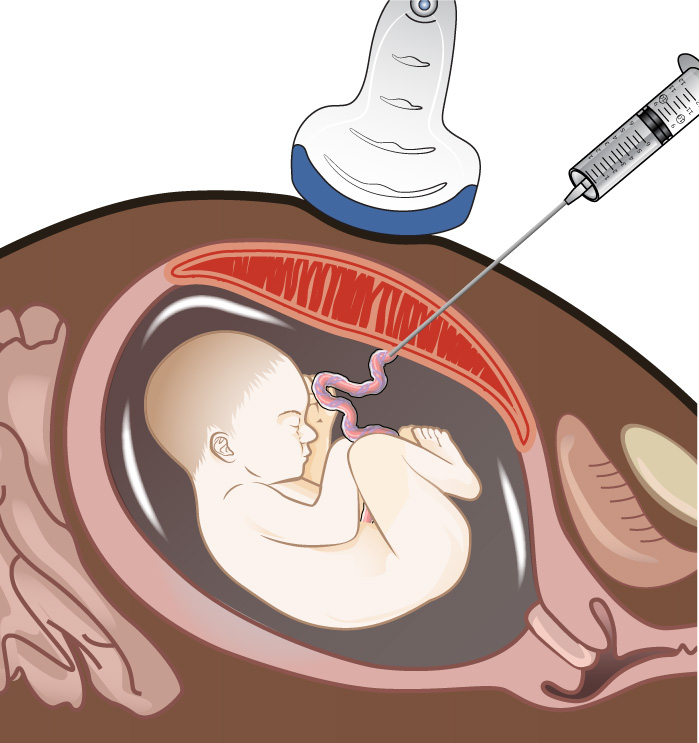

Percutaneous umbilical blood sampling (PUBS) looks for specific genetic or blood disorders in the fetus. PUBS can be performed starting at 18 weeks’ gestation and is used to diagnose anemia, thrombocytopenia, other blood disorders, chromosomal abnormalities, infection, and isoimmunization in the fetus. PUBS provides the most accurate diagnosis of Down syndrome during pregnancy. However, it is not commonly used because it is riskier than other screening tests, and it cannot be performed until the second trimester or later in pregnancy. During the procedure, the health care provider guides a needle, with the aid of an ultrasound, into a blood vessel of the umbilical cord to collect a blood sample. The sample is then sent to the lab to be analyzed for genetic disorders and other fetal health considerations. This procedure can also be used to deliver medications or blood transfusions to a fetus.[22] See Figure 9.21[23] for an illustration of PUBS.

The nurse is often responsible for reinforcing client education on what to expect before, during, and after the procedure. If the pregnant woman is having a PUBS test after 23 weeks’ gestation, they may be instructed not to eat or drink anything several hours before the test in case there are complications during the test that require surgery. After PUBS, the nurse will monitor the fetal heart rate for a short time. The nurse will also inform the pregnant woman that they may experience cramping after the test and should avoid strenuous activity for the rest of the day.[24]

Potential risks of having PUBS are as follows[25]:

- Early delivery via emergent C-section

- Miscarriage

- Blood loss in the fetus and pregnant woman

- Cord hematoma

- Slow fetal heart rate

- Infection in the fetus or uterus

- Separation of the placenta from the uterus

The nurse will instruct the pregnant woman to watch for any signs or symptoms of infection after the procedure. The pregnant woman is advised to call the doctor’s office if they experience chills, cramps that do not get better throughout the day, decreased fetal movement, fever, leaking amniotic fluid, or vaginal bleeding. Results are normally available a few days after the procedure is done. If the results are positive, the provider will go over the results with the pregnant woman and may refer the pregnant woman and their partner to a genetic counselor for further guidance.[26]

Umbilical Doppler Study

An umbilical Doppler study is used to evaluate the blood flow in the umbilical arteries, the blood vessels located in the umbilical cord. The Doppler ultrasound is used with other tests when the fetus shows signs of not growing well. This test can be performed as early as 22 weeks’ gestation and is performed during the second and third trimesters. A normal test result shows normal blood flow in the umbilical artery. If the test shows abnormal blood flow in the umbilical arteries, it can mean that insufficient oxygen is being delivered to the fetus and further testing is required.[27]

Fetoscopy

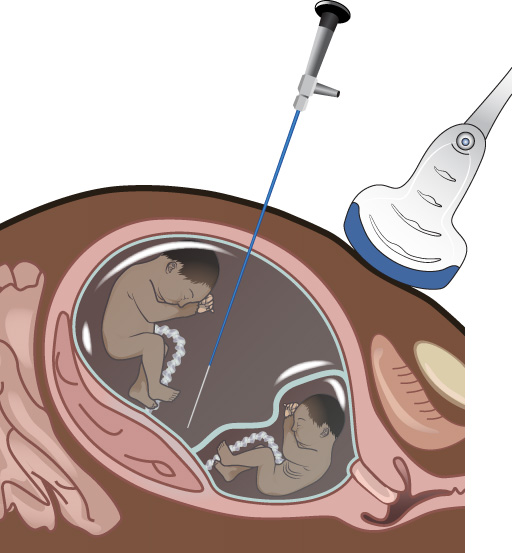

A fetoscopy is a diagnostic test that can be used to treat congenital disorders. It involves insertion of a thin fiber-optic tube called a fetoscope into the uterus through a small incision made in the abdomen of the pregnant woman. See Figure 9.22[28] for an illustration of a fetoscopy. The fetoscope has a small camera on the end, which allows for visualization of the placenta, amniotic sac, and fetus. The fetoscope is hollow, which allows the provider to insert surgical tools through it to repair certain fetal conditions or collect tissue samples. Fetoscopy is performed after 12 weeks’ gestation, depending on the reason it is being done.[29]

A fetoscopy may be recommended for several reasons. Twin-to-twin transfusion syndrome is a condition that can be life-threatening and occurs when identical twins in the womb do not receive an equal share of blood. By using a laser through the fetoscope, the blood vessels that cause uneven blood flow can be closed off.

In amniotic band syndrome, bands of tissue from the amniotic sac can entangle the fetus, leading to restricted blood flow or even amputation of limbs or organs. A fetoscopy procedure can be used to insert a laser device that cuts and releases the bands of tissue surrounding the fetus. Fetoscopy may also be done for treatment of placental tumors, spina bifida, and other congenital conditions. Risk factors include rupture of membranes, initiation of labor, or infection.[30]

Health Teaching During Second Trimester Visits

Education in the second trimester of pregnancy focuses on fetal milestones, nutrition and weight gain of the pregnant woman, and signs of complications of pregnancy. At 16 weeks of gestation, external genitalia of the fetus are more easily viewed during the ultrasound, and meconium is starting to be produced. At 23 to 24 weeks, the fetus becomes viable because the alveoli in the lungs are starting to produce surfactant. Viability at this point in the pregnancy is defined as the fetus having the capability of living outside the uterus.[31]

The importance of a healthy diet is reinforced in the second trimester. The nurse uses the client’s weight gain, maintenance, or loss as the screening tool for adequate nutritional intake. Any weight loss is investigated for an underlying cause, such as illness or lack of money for food. Unexpected weight gain may be due to fluid retention or a sedentary lifestyle rather than eating non-nutritious foods. The nurse can help identify nutritious foods the client likes and can afford.[32]

Health teaching in the second trimester may discuss the same symptoms, such as vaginal bleeding, but the complications change after 20 to 24 weeks of gestation. Uterine cramping and vaginal bleeding indicate possible miscarriage when the client is at less than 20 weeks’ gestation. These same symptoms indicate possible preterm labor after 20 weeks. The presence of edema before 20 weeks may indicate heart disease; after 20 weeks, edema may be an early sign of a hypertensive disorder of pregnancy. Additional teaching topics during the second trimester of pregnancy include the following[33]:

- Fetal growth and development

- Quickening

- Reinforcement of health promotion activities

- Physiologic changes during the second trimester of pregnancy

- Psychological changes during the second trimester of pregnancy

- Common discomforts of pregnancy

- Review signs of complications

- Fetal movement

- Rho(D) immune globulin if Rh negative

- Laboratory testing and results

- Choosing a newborn health care provider

- Breast-feeding

- Childbirth preparation

- Birth plan

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “6201e447a83e81d93ee4d66beb063558c62ce402” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/11-3-care-in-the-second-trimester-of-pregnancy ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “e1ebee14297c60d3db11f036e837b059d50ac89d” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/13-2-prenatal-testing-during-the-second-trimester ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2022). Amniocentesis. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/amniocentesis/about/pac-20392914 ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “75133ccba30b315cb66cbbad4624be21d6f6164d” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/13-2-prenatal-testing-during-the-second-trimester ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “24e13dba25dfab06d51ff1d30144080aafd29a5f” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/13-2-prenatal-testing-during-the-second-trimester ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

A complication associated with preeclampsia that can cause life-threatening bleeding issues during labor and postpartum evidenced by hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count.

Measures the maternal serum levels of four pregnancy markers (alpha fetoprotein, hCG, unconjugated estriol, and inhibin-A), and a blood sample is drawn when the client is between 15 and 22 weeks of gestation.

A protein produced in the liver of a developing fetus, often measured in prenatal tests to assess the risk of fetal abnormalities.

A prenatal procedure where amniotic fluid is extracted from the uterus for testing, often used to detect genetic disorders.

A procedure in which the health care provider guides a needle, with the aid of an ultrasound, into a blood vessel of the umbilical cord to collect a blood sample. The sample is then sent to the lab to be analyzed for genetic disorders and other fetal health considerations.

A diagnostic test which involves the insertion of a thin fiber-optic tube called a fetoscope into the uterus through a small incision in the abdomen of the pregnant client in order to treat congenital disorders.