9.5 Common Discomforts of Pregnancy and Relief Measures

A pregnant woman often experiences physical discomforts due to the physiologic and anatomic changes that occur throughout the pregnancy. Nurses provide health teaching that includes discussion on common discomforts and when they tend to occur during the pregnancy, their physiologic or anatomic causes, and suggested relief measures. Nurses also teach about self-care during pregnancy to prevent complications and provide relief from the common discomforts of pregnancy. Health teaching topics include regular exercise, good hygiene, comfortable clothing, adequate sleep and rest, employment accommodations, and recommended immunizations.[1]

Common discomforts occurring during pregnancy are not confined to one body system or to a specific time during gestation. Relief measures for these discomforts are often nonpharmacologic self-care actions that can easily be performed by the pregnant woman. When self-care actions are not effective, pharmacologic relief measures may be prescribed by the health care provider. These common discomforts and their relief measures are further discussed in the following subsections.[2]

Nausea and Vomiting

Nausea and vomiting, commonly called morning sickness, are common discomforts that typically begin around Weeks 4 – 6 of gestation and resolve by 16 weeks of gestation. Nausea and vomiting are caused by higher serum levels of estrogen, progesterone, and hCG in the first part of the pregnancy, as well as motility changes in the gastrointestinal system.[3]

Health teaching about self-care measures to relieve nausea and vomiting includes eating small, frequent snacks every one to two hours while awake and not drinking fluids immediately before, during, or after eating. Ginger tea, ginger ale, and lemonade may be effective in relieving nausea. Consuming dry toast, saltine crackers, or cold pasta and avoiding greasy or spicy foods have also been found to decrease the severity of nausea and vomiting in some pregnant women. The pregnant woman will need to discover a personal pattern of eating and avoiding specific foods to find relief from nausea and vomiting. Additional nonpharmacologic measures include increasing vitamin B6, using acupressure wrist bands, or taking prenatal vitamins at night instead of in the morning.[4]

Pharmacological interventions are prescribed by health care providers to treat hyperemesis gravidarum (severe vomiting during pregnancy) to prevent dehydration and weight loss. Commonly prescribed antiemetics during pregnancy are pyridoxine, doxylamine, ondansetron, and promethazine. Nurses teach clients how to administer the antiemetics and when to notify the health care provider of signs of dehydration, such as decreasing weight, decreased blood pressure, and increased or thready pulse.[5] Read more information about these medications in the following box.

Medications Used to Treat Nausea and Vomiting During Pregnancy

Several medications are routinely prescribed to treat nausea and vomiting during pregnancy when nonpharmacologic measures are not effective.

Combination Medication: Pyridoxine and Doxylamine

- Classification: Pyridoxine is a vitamin B6 supplement, and doxylamine blocks histamine H1-receptors and acetylcholine receptors.

- Route/Dosage: Two tablets by mouth at bedtime on an empty stomach or as prescribed.

- Mechanism of Action: Decreased vitamin B6 is associated with nausea, so B6 supplementation helps relieve nausea. The antihistamine dulls motion sensation in the inner ear, thus decreasing nausea.

- Contraindications: Clients currently taking a monoamine oxidase inhibitor (MAOI).

- Side Effects: Dry mouth and throat, headache, dizziness, drowsiness, or muscle weakness.

- Adverse Effects: Vision problems, tachycardia, or confusion.

- Health Teaching: Take the medication at night if only prescribed once a day; take the medication on time when more than one dose is prescribed per day; and schedule the doses one hour before or two hours after a meal.

Ondansetron

- Route/Dosage: 4–8 mg by mouth, sublingual, intramuscular (IM), and intravenously (IV) every eight hours or as prescribed.

- Mechanism of Action: Selective 5-HT3 antagonist.

- Contraindications: Prolonged QT interval or serotonin syndrome.

- Side Effects: Drowsiness, headache, fatigue, diarrhea, or constipation.

- Adverse Effects: Blurred vision, fainting, agitation, hallucinations, prolonged QT interval, or serotonin syndrome.

- Health Teaching: Take the medication on time as prescribed and schedule the doses one hour before or two hours after a meal.

Promethazine

- Route/Dosage: 12.5–25 mg by mouth, per rectum, IM, or IV every six hours as needed.

- Mechanism of Action: Blocks histamine H1-receptors.

- Contraindications: Bone marrow suppression.

- Side Effects: Drowsiness, dizziness, or itching.

- Adverse Effects: Anaphylaxis, seizures, nightmares, or hallucinations.

- Health Teaching: Take the medication on time when prescribed more than one dose per day and schedule the doses one hour before or two hours after a meal; rectal suppositories can be inserted as prescribed regardless of when meals are consumed.

Heartburn and GERD

Heartburn, also known as dyspepsia, is caused by increased progesterone levels. Progesterone supports the pregnancy but also causes relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter and slows emptying of the stomach. Heartburn is experienced most often in the second half of pregnancy and increases in severity in the final weeks of gestation because of the enlarged uterus. Heartburn can evolve into gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD).[6]

Nurses teach clients to try to relieve dyspepsia by remaining upright after eating and not eating within two hours of lying down to sleep. Symptoms of dyspepsia can also be decreased by avoiding wearing tight clothes around the waist, by eating slowly and in smaller portions, and avoiding high-fat or spicy foods. Some clients find that drinking a glass of low-fat milk decreases the burning sensation, but drinking a glass of water can aggravate the burning sensation.[7]

Pharmacologic measures to treat heartburn are antacid tablets containing calcium or a combination of magnesium and aluminum. Antacids should be taken with meals or immediately after a meal for optimal effectiveness. Antacids should not be taken with iron supplements because they decrease the absorption of iron. For severe heartburn and/or GERD, histamine-2 blockers (such as famotidine), or a proton pump inhibitor (such as omeprazole), may be prescribed or purchased over the counter after discussion with the health care provider.[8]

Constipation

Constipation during pregnancy is caused by decreased gastric motility related to increased progesterone levels. Slowed gastric motility allows more nutrients and water to be absorbed to support the pregnancy and the growth and development of the fetus, but the increased water absorption results in firmer stools that are more difficult to evacuate. Calcium and iron supplements in prenatal vitamins also contribute to hard stools.[9]

Nurses teach clients how to prevent constipation with increased fluid and fiber intake, as well as increased physical activity. Clients are encouraged to drink eight glasses of water each day and increase dietary fiber intake by eating whole grain breads, bran cereals, and fresh fruits and vegetables. Decreasing intake of refined sugars and cheese can also help prevent constipation. Increasing regular exercise such as walking or swimming for 30 minutes, four or five times a week, or participating in yoga are healthy ways to exercise during pregnancy.[10]

Pharmacologic measures to treat constipation include psyllium to increase bulk of the stool or stool softeners (such as docusate or polyethylene glycol) to add water back into the stool to ease evacuation. These medications are available over the counter and can be taken after discussion with the health care provider. However, stimulant laxatives (such as bisacodyl) that increase gastric motility are not recommended during pregnancy.[11]

Hemorrhoids

Hemorrhoids often occur during pregnancy due to a combination of increased progesterone and the weight of the growing uterus in the mother’s abdomen. Progesterone relaxes the veins in the rectum, and the weight of the uterus increases vasodilation. The risk for developing hemorrhoids increases due to straining during bowel movements due to constipation and/or low-fiber intake. Prevention of hemorrhoids includes increasing consumption of high-fiber foods, increasing water intake, increasing physical activity by walking, and avoiding sitting for long periods of time.[12]

Pharmacologic treatment of hemorrhoids may include application of witch hazel, an astringent; a combination of phenylephrine, glycerin, and petroleum (Preparation H); or a combination of hydrocortisone and bismuth ointment (Anusol). These products decrease the swelling of the rectal tissue and are available over the counter after discussion with the health care provider.[13]

Fatigue and Insomnia

Fatigue is caused by increased metabolic demands that occur during pregnancy and the production of progesterone and relaxin. Fatigue occurs more frequently during the early weeks of pregnancy due to rapid growth of the fetus and uterus, as well as the final weeks when the pregnant woman experiences several physiologic adaptations to pregnancy and often has difficulty sleeping. Insomnia during pregnancy is often caused by a surge in estrogen and progesterone levels in early pregnancy and common discomforts of leg cramps, back pain, and nocturia. Later in pregnancy, increasing fetal movements may cause insomnia. Nurses encourage pregnant women to maintain a consistent sleep-wake schedule, get enough sleep, avoid drinking fluids before bedtime, and take short naps. They can also try sleeping on their left side, using support pillows, and elevating the head of their bed. Chamomile tea may be used to relax and fall asleep, and relaxation techniques performed while lying in bed may help the pregnant woman to fall asleep more easily. Pharmacologic measures include melatonin, an over-the-counter sleep aid.[14]

Dizziness and Syncope

Occasional dizziness may occur during pregnancy for several reasons. Vasodilation often occurs due to decreased peripheral vascular resistance caused by increased levels of progesterone and relaxin hormones. Vasodilation causes decreased blood pressure and/or orthostatic hypotension that can result in dizziness. Nurses teach clients to stay hydrated, rise from sitting or standing slowly, and to not make sudden moves. Dizziness can also be caused by low blood glucose levels, so nurses instruct clients to eat at regular times and eat healthy snacks as needed to prevent low blood glucose levels. A third cause of dizziness can be anemia. Nurses teach clients to take prenatal vitamins and consume foods high in iron.[15] Syncope may also occur due to vasodilation, low blood glucose levels, and anemia, but it can also be caused by impaired cardiac function such as transient tachycardia of pregnancy or preexisting cardiac disease. The health care provider should be notified of syncope for follow-up evaluation.[16]

The enlarging uterus places pressure on the vena cava starting around 28 weeks of gestation, which can cause decreased blood flow back to the heart (referred to as vena cava syndrome). Symptoms of vena cava syndrome are dizziness, weakness, and nausea when lying flat on their back. See Figure 9.13[17] for an illustration of positioning that can cause vena cava syndrome. Nurses teach pregnant women to sleep and rest in a lateral position rather than flat on their back once they reach 28 weeks of gestation to avoid vena cava syndrome.[18]

Breast Tenderness

Breast tenderness is due to increased estrogen levels during pregnancy that stimulate milk ducts and glands to increase in both number and size. It may be helpful for pregnant women to wear a good-fitting bra while awake and asleep to provide support and decrease breast tenderness. It may also be necessary to purchase new bras in larger sizes as the breasts enlarge.[19]

Shortness of Breath

Shortness of breath and dyspnea can occur during pregnancy due to a rise in progesterone, estrogen, and prostaglandin hormones that cause lung congestion. Furthermore, the diaphragm rises as much as 4 centimeters, and the rib cage diameter expands as much as 6 centimeters as the enlarged uterus pushes the intestines into the rib cage and decreases the size of the thoracic cavity. Nurses teach pregnant women to maintain good posture and sleep in an upright position with several pillows to help make breathing easier. However, sudden, acute shortness of breath can indicate a complication such as a pulmonary embolism and should be reported to the health care provider, or the client should obtain emergency care.[20]

Lower Back Discomfort

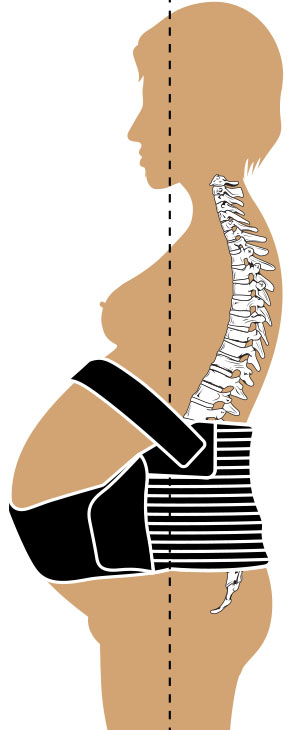

Lower back discomfort occurs because of anatomic and physiologic changes during pregnancy. Progesterone and relaxin cause the ligaments to become more elastic, and the weight of the growing uterus causes an increase in the curvature of the spine. Nurses teach clients to perform pelvic rock exercises, wear low-heeled shoes, and possibly wear a maternity belt. A maternity belt helps lift the uterus, support the lower uterus and back, relieve urinary frequency and vulvar edema, and promote lower back comfort.[21] See Figure 9.14[22] for an illustration of a maternity belt.

View a supplementary YouTube video[23] about pelvic rock exercises: Safe Pregnancy Exercise: Pelvic Rock | Ohio State Medical Center.

Urinary Frequency

The pressure of the enlarging uterus on the bladder commonly causes urinary frequency throughout pregnancy. However, nurses should perform additional focused assessments to make sure urinary frequency is not caused by a urinary tract infection. To prevent nocturia, pregnant women are encouraged to avoid fluid intake within two hours of bedtime. Nurses teach pregnant women to avoid caffeine or restrict caffeine intake during pregnancy to less than 200 mg per day to help decrease urinary frequency.[24]

Itching

Itching during pregnancy is commonly caused by increased blood supply to the skin, as well as stretching of the skin due to the growing uterus. However, nurses should perform additional assessments to ensure itching is not a sign of cholestasis or liver disease. Nurses provide health teaching to relieve itching such as taking cool baths, using unscented lotions or oils on the skin, and avoiding scratching to prevent skin breakdown.[25]

Headache

Headaches during pregnancy can be caused by dehydration, low blood glucose, or difficulty sleeping. Increased estrogen levels can also cause headaches. However, sudden onset of a severe headache can indicate a serious medical condition, so nurses advise pregnant women to obtain emergency care should this symptom occur. Nurses provide health teaching about preventing headaches by keeping well-hydrated, eating meals and snacks at regular times throughout the day, and maintaining a consistent sleep-wake cycle.[26]

Edema

Dependent edema is common in late pregnancy. Edema during pregnancy results from decreased peripheral vascular resistance due to increased levels of estrogen and progesterone, as well as the pressure of the enlarged uterus on the lower extremities. However, increasing edema can also be a sign of preeclampsia, especially if the edema is generalized, so nurses teach clients to report this symptom to their health care provider for follow-up evaluation. Nurses provide health care teaching to reduce edema in pregnant women by wearing loose, nonrestrictive clothing; using a maternity belt; avoiding prolonged standing or sitting; elevating their legs when sitting; and reducing salt intake. Compression socks are also helpful for reducing edema, especially in clients whose occupation requires prolonged standing.[27]

Varicosities

Varicosities are swollen, twisted veins that are visible just under the skin. They usually appear in the legs but can also occur in other parts of the body. They occur during pregnancy because of decreased peripheral vascular resistance in the lower extremities, as well as the pressure of the enlarged uterus on the perineum. Nurses provide health teaching to reduce the severity and discomfort of varicosities by avoiding prolonged standing or sitting, elevating their legs when sitting, and wearing a maternity belt and/or compression stockings.[28]

Leg Cramps

Leg cramps during pregnancy can be caused by elevated or decreased levels of calcium, potassium, or magnesium in the diet. However, sudden calf pain with redness and swelling can also be a sign of deep vein thrombosis and should be immediately reported to the health care provider. Nurses teach pregnant women that leg cramps can be relieved by dorsiflexing the foot (i.e., pulling it up towards the body) and massaging the affected muscle. Regular exercise and a nutritious diet can also prevent leg cramps.[29]

Round Ligament Pain

The round ligaments attach the uterus to the pelvis. As the uterus grows larger and moves upwards out of the pelvis and into the abdomen, stretching of the round ligaments occurs. This stretching can cause pain in the right or left lower abdominal quadrant. However, sudden, severe lower abdominal pain can also be caused by appendicitis or other serious medical conditions requiring immediate medical evaluation. Round ligament pain typically occurs between 14 and 27 weeks of gestation. Nurses teach clients that round ligament pain can be relieved by applying warm compresses, taking baths, lying on one’s side with the knees drawn up toward the abdomen, and using a maternity belt.[30]

Braxton-Hicks Contractions

Braxton-Hicks contractions are spontaneous, mild uterine contractions that occur throughout the pregnancy. Braxton-Hicks contractions normally have no effect on the cervix until the final weeks of pregnancy when the progesterone levels drop and the oxytocin level increases. Dehydration can increase the frequency and intensity of Braxton-Hicks contractions, especially in the final weeks of the pregnancy. Nurses teach clients strategies to minimize the discomfort and frequency of these contractions, such as adequate fluid intake and the use of a maternity belt. Maternity belts help by supporting the uterus and lifting the fetus in the lower uterine segment.[31]

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Medical terminology 2e. Open RN | WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/medterm/ ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “4a25573a0e278f97388458baa77a0b25fc5c7e5f” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/10-3-common-discomforts-of-pregnancy ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Medical terminology 2e. Open RN | WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/medterm/ ↵

- “26bf1be1a1812ead2a431ab0672e24a4dd343de9” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/10-3-common-discomforts-of-pregnancy ↵

- Ohio State Wexner Medical Center. (2022, April 15). Safe pregnancy exercise: Pelvic rock | Ohio State Medical Center [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xYNUPZLVg-M ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Giles, A., Prusinski, R., & Wallace, L. (2024). Maternal newborn nursing. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/1-introduction ↵

Severe vomiting during pregnancy.

Heartburn.

Occurs when the enlarging uterus places pressure on the vena cava starting around 28 weeks of gestation, which can cause decreased blood flow back to the heart.

Swollen, twisted veins that are visible just under the skin.