8.2 Review of Anatomy and Physiology of the Male and Female Reproductive Systems

Anatomy of the Male Reproductive System

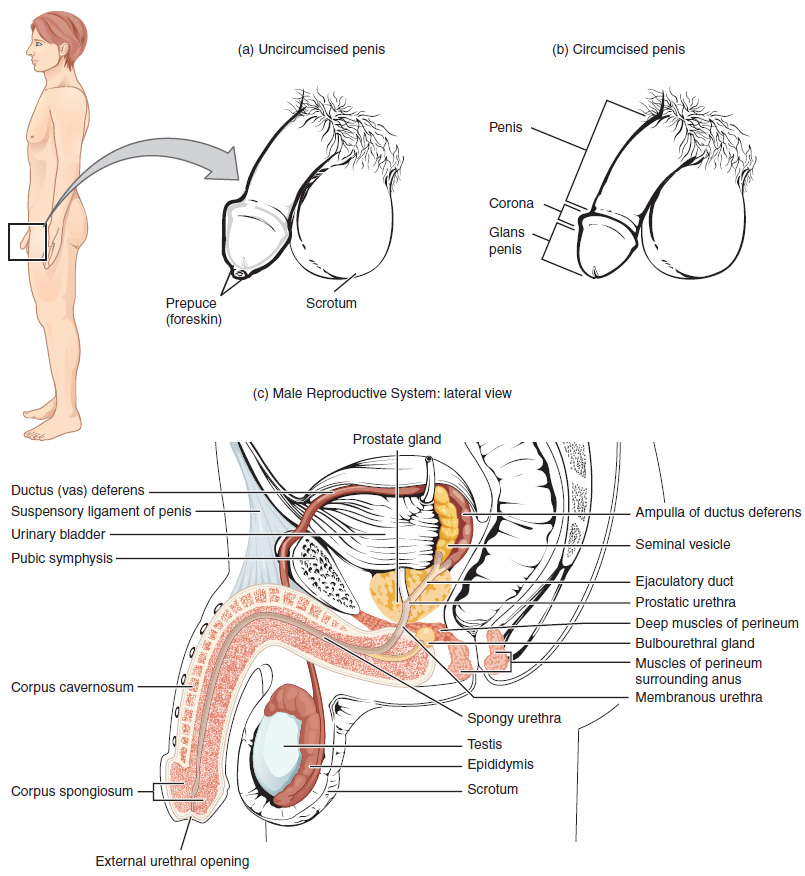

The structures of the male reproductive system include the testes and epididymis in the scrotum; the vas deferens, seminal vesicles, and bulbourethral glands; the prostate gland; and the penis. These structures are well-vascularized with many glands and ducts to promote the formation, storage, and ejaculation of sperm for fertilization and to also produce testosterone.[1]

See Figure 8.1[2] for an illustration of these structures of the male reproductive system.

Testes

The testes are the primary male reproductive organs. They produce both sperm and androgen (i.e., the male sex hormone testosterone) and are active throughout the reproductive life span of the male. There are two testes, each approximately 4 to 5 cm in length, that are housed within the scrotum, an external pouch.[3]

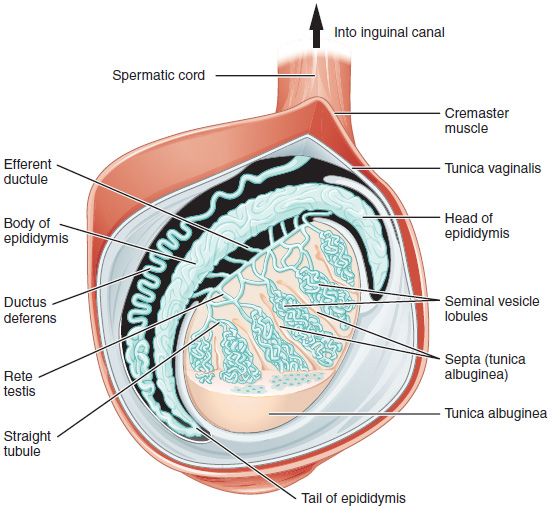

During the seventh month of the developmental period of a male fetus, each testis moves through the abdominal musculature to descend into the scrotal cavity. This is called the “descent of the testis.” Cryptorchidism is the clinical term used when one or both of the testes fail to descend into the scrotum prior to birth.[4] See Figure 8.2[5] for an illustration of a testicle.

The spermatic cord is a bundle of blood vessels, nerves, and ducts that connect the testicles to the abdominal cavity through the inguinal canal. There are several disorders related to the spermatic cord. The spermatic cord is sensitive to testicular torsion, in which the testicle rotates within its sac and blocks its own blood supply. An inguinal hernia can occur, referring to protrusion of abdominal contents through the inguinal canal, sometimes extending into the scrotum. Varicose veins can occur in the spermatic cord, referred to as varicocele. Though often asymptomatic, about one in four men with varicocele may experience infertility.

Each testis is divided by septa into 300 to 400 structures called lobules. Within the lobules, sperm develop in structures called seminiferous tubules. Newly produced sperm leave the seminiferous tubules and travel to the epididymis, a coiled tube on top of the testes where the newly formed sperm continue to mature for an average of 12 days. As they are moved along the length of the epididymis, the sperm further mature and acquire the ability to move under their own power. Once inside the female reproductive tract, they will use this ability to move independently toward the unfertilized egg. Mature sperm are stored in the tail of the epididymis until ejaculation occurs.[6]

During ejaculation, sperm exit the tail of the epididymis and are pushed by smooth muscle contraction to the vas deferens. Sperm make up only five percent of the final volume of semen, the thick, milky fluid that a male ejaculates. This fluid is produced by accessory glands of the male reproductive system, the seminal vesicles, the prostate, and the bulbourethral glands. From here, the semen travels through the urethra to the outside of the body during ejaculation.

Because the vas deferens is easily accessible within the scrotum, surgical sterilization to interrupt sperm delivery can be performed by cutting and sealing a small section of the vas deferens, referred to as a vasectomy. Read more about vasectomy in the “Contraception” section.

Prostate and Bulbourethral Glands

As sperm pass through the vas deferens at ejaculation, they mix with fluid produced by the associated seminal vesicle. Seminal vesicle fluid contains large amounts of fructose, which is used by the sperm mitochondria to generate energy to allow movement through the female reproductive tract. The seminal fluid, now containing both sperm and seminal vesicle secretions, moves into the associated ejaculatory duct. The paired ejaculatory ducts transport the seminal fluid into the prostate gland.[7]

The prostate is a gland that is anterior to the rectum at the base of the bladder and surrounds the urethra. A normal prostate gland is the size of a walnut. It secretes an alkaline, milky fluid in semen to coagulate (thicken) and then decoagulate the semen following ejaculation. The temporary thickening of semen helps retain it within the female reproductive tract, providing time for sperm to utilize the fructose provided by seminal vesicle secretions. When semen regains its fluid state, the sperm can pass farther into the female reproductive tract.[8]

The final addition to semen is made by two bulbourethral glands that release a thick, salty fluid to lubricate the end of the urethra and the vagina, as well as cleanse urine residue from the urethra. The fluid from these accessory glands is released after the male becomes sexually aroused and shortly before the release of the semen, so it is often referred to as pre-ejaculate. It is possible for bulbourethral fluid to pick up sperm already present in the urethra and cause pregnancy. Semen moves into the penis via the urethra, a multifunction anatomical structure that also transports urine from the bladder.[9]

Penis

The penis is a male reproductive organ that is flaccid during nonsexual actions, such as urination, and becomes stiff and rod-like during sexual arousal. When erect, the stiffness of the penis allows it to penetrate into the vagina and deposit semen into the female reproductive tract, referred to as sexual intercourse or coitus.

The glans penis refers to the tip of the penis. Circumcision is the surgical removal of the foreskin, also called prepuce, a fold of skin that covers the tip of the penis.

Physiology of the Male Reproductive System

Testosterone

Testosterone is an androgen (i.e., male sex hormone produced in the testes). In a male fetus, testosterone is secreted by the testes by the seventh week of development, with peak concentrations reached in the second trimester. This early release of testosterone results in the anatomical differentiation of the male sexual organs. In childhood, testosterone concentrations are low and then increase during puberty, the period during which adolescents develop secondary sex characteristics, such as growth of pubic hair. During puberty, the production of sperm begins.[10] Read more about development of secondary sex characteristics in the “Sexual Development Across the Life Span” section of this chapter.

Testosterone is released into the systemic circulation and plays an important role in muscle development, bone growth, development of secondary sex characteristics, and maintenance of libido (i.e., sex drive) in both males and females. In females, the ovaries secrete small amounts of testosterone, although most is converted to estradiol (a form of estrogen). A small amount of testosterone is also secreted by the adrenal glands in both sexes.[11]

Sperm

Spermatogenesis, the production of sperm, occurs in the testes. Spermatogenesis requires a two- to three-degree lower temperature than body temperature, which is why it occurs outside of the body. It begins at puberty, after which time sperm are produced constantly throughout a man’s life.

One production cycle to form sperm takes approximately 64 days. Sperm counts, the total number of sperm a man produces, slowly decline after age 35.

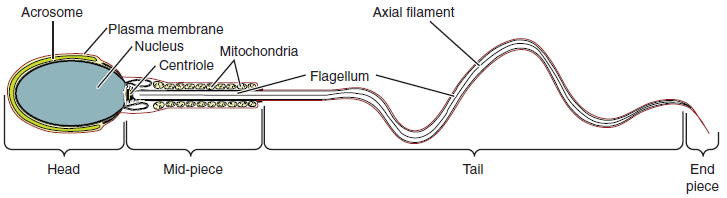

Sperm, the male reproductive cell, are smaller than most cells in the body. In fact, the volume of a sperm cell is 85,000 times less than that of the egg (female reproductive cell). Approximately 100 to 300 million sperm are produced each day, whereas women typically ovulate only one oocyte (egg) per month. As is true for most cells in the body, the structure of sperm cells speaks to their function. Sperm have a distinctive head, midpiece, and tail region. See Figure 8.3[12] for an illustration of a sperm.

Ejaculation refers to the ejection of semen from the penis during orgasm, the climax of sexual stimulation.[13]

View a supplementary video[14] on the route of sperm through the male body during ejaculation: Sperm Release Pathway.

Penile erection is caused by vasocongestion of the penile tissues, as more arterial blood flows into the penis than is leaving in the veins.[15] Priapism is a disorder in which the penis maintains a prolonged, rigid erection for four hours or longer in the absence of stimulation. Priapism that is caused by blood not being able to leave the penis is a medical emergency requiring prompt surgery to prevent damage to the penis. If not treated promptly, priapism can progress to permanent erectile dysfunction.[16]

Common disorders of the male reproductive system are discussed in the “Male Reproductive System Disorders” section.

Anatomy of the Female Reproductive System

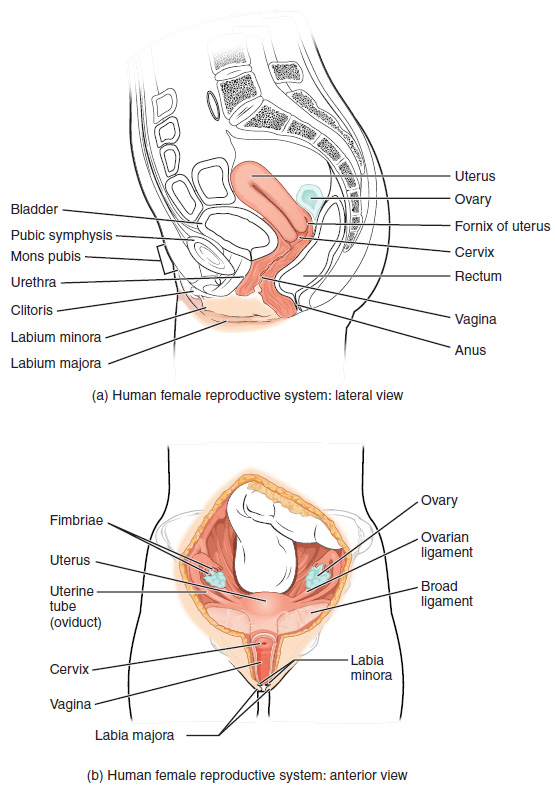

Anatomy of the female reproductive system includes the external genitals, the internal reproductive system, and the breasts.

External Female Genitals

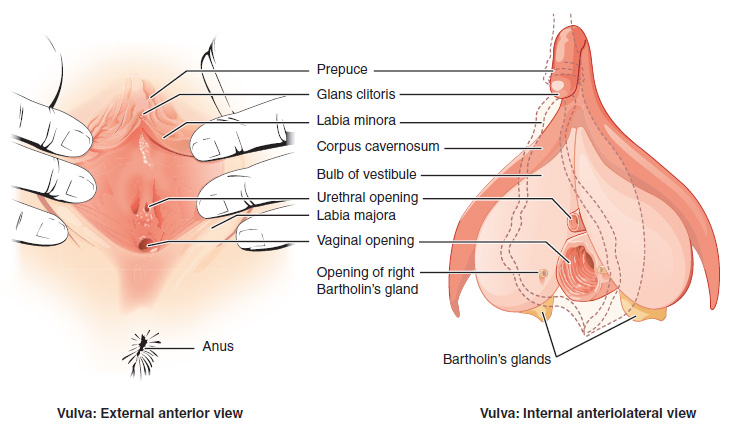

See Figure 8.4[17] for an illustration of the external female genitals. The external female reproductive structures, referred to collectively as the vulva, include the following[18]:

- The mons pubis is a pad of fat that is located anteriorly over the pubic bone. After puberty, it becomes covered in pubic hair.

- The labia majora are larger outer folds of hair-covered skin that begin just posterior to the mons pubis.

- The labia minora are thinner, hairless, and more pigmented folds found medially to the labia majora.

- Although they naturally vary in shape and size from woman to woman, the labia minora serve to protect the female urethra and the entrance to the female reproductive tract.

- The superior, anterior portions of the labia minora come together to encircle the clitoris. The clitoris is erectile tissue that originates from the same fetal cells as the penis and has abundant nerves that are important in sexual sensation and orgasm.

- The vestibule is the area between the labia minora and behind the clitoris that contains the urethral and vaginal openings. It is flanked by outlets to the vestibular glands, also known as Bartholin's glands, that secrete mucus to keep the vestibular area moist.

- In females, the perineum is the area between the vaginal opening and the anus.

Internal Female Reproductive Organs

The internal female reproductive organs include the vagina, uterus, cervix, ovaries, and Fallopian tubes. See Figure 8.5[19] for an illustration of the internal and external structures of the female reproductive system.

Vagina

The vagina is a muscular canal that is approximately ten centimeters long. It serves as the entrance to the reproductive tract, as well as the exit from the uterus during menstruation and childbirth.[20]

The vagina is composed of smooth muscle that allows for expansion during intercourse and childbirth. The vagina is lined with mucous membranes that secrete mucus to keep it moist. The superior portion of the vagina meets the cervix (the opening and lower part of the uterus). The inferior portion of the vagina may have a thin, perforated hymen that partially surrounds the opening to the vagina.[21]

The vagina contains a normal population of healthy bacteria called normal flora that helps protect against infection. In a healthy woman, the most common type of normal flora is lactobacillus that secretes lactic acid. The lactic acid protects the vagina by maintaining an acidic pH (below 4.5). Lactic acid, in combination with other vaginal secretions, makes the vagina a self-cleansing organ. However, douching can disrupt the normal balance of healthy microorganisms and increases a woman’s risk for infections and irritation. It is recommended that women do not douche and that they allow the vagina to maintain its normal healthy population of protective normal flora.[22]

Uterus

The uterus is a muscular, pear-shaped organ that is approximately 5 cm wide by 7 cm long. It is composed of three sections[23]:

- The inferior portion, called the cervix, connects the uterus and the vagina.

- The middle section of the uterus is called the corpus (body of the uterus).

- The superior portion is called the fundus.

An opening in the middle of the cervix allows menstrual blood to exit and sperm to enter the uterus. The cervix dilates (opens) during childbirth to allow the baby to exit the mother’s body. The corpus of the uterus expands during pregnancy. The fundus is the location of the uterus that is commonly felt by the health care provider during prenatal exams to indirectly measure the growth of the fetus.[24]

The wall of the uterus is made up of these three layers[25]:

- Perimetrium: The serous membrane surrounding the uterus.

- Myometrium: A thick layer of smooth muscle responsible for uterine contractions.

- Endometrium: The innermost layer that provides the site for implantation of a fertilized egg or sheds during menstruation if an egg is not fertilized.

Ovaries

The ovary is the female reproductive gland located in the pelvic cavity. There are two ovaries, one at the entrance to each Fallopian tube, which are attached to the uterus via the ovarian ligaments. The ovaries create oocytes (eggs) and hormones.[26]

Fallopian Tubes

The Fallopian tubes transport oocytes from the ovary to the uterus. Each of the Fallopian tubes is close to, but not directly connected to, the ovary, so the fimbriae catch the oocyte like a baseball in a glove. The middle region of the Fallopian tube, called the ampulla, is where fertilization often occurs. The fertilized egg then moves from the Fallopian tube into the uterus, where it implants into the endometrium.[27]

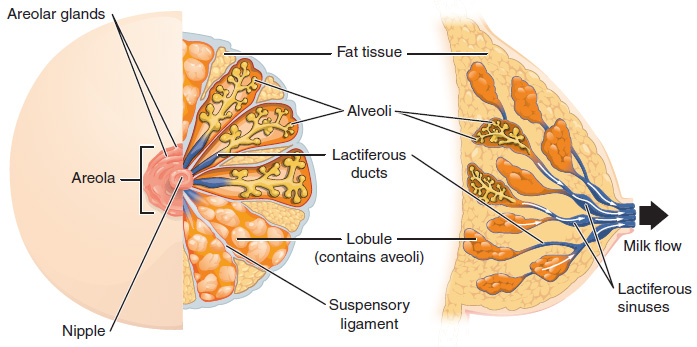

Breasts

Although the breasts are located far from the other reproductive organs, they are considered accessory organs of the female reproductive system. The function of female breasts is to supply milk to an infant in a process called lactation.[28]

The external features of the breast include a nipple surrounded by a pigmented areola. The areolar region is characterized by small, raised areolar glands, also referred to as Montgomery’s glands, that secrete lubricating fluid during lactation to protect the nipple from chafing. When a baby nurses (i.e., draws milk from the breast), the entire areolar region is taken into their mouth.[29]

A breast is made up of three main parts: lobules, ducts, and connective tissue. The lobules are the mammary glands composed of alveoli (tiny sacs) that produce milk. The lactiferous ducts are tubes that carry milk to the nipple. The connective tissue (which consists of fibrous and fatty tissue) surrounds and holds everything together.[30]

An infant can draw milk from the lobules and through the ducts and the nipple by suckling. Alveoli are surrounded by fat tissue, which determines the size of the breast. Breast size differs among individuals and does not affect the amount of milk produced.[31] See Figure 8.6[32] for an illustration of a breast and milk flow.

Some women have fibrocystic breasts with connective tissue that feels lumpy or ropelike in texture. Fibrocystic breast changes are common and no longer considered a disease, although it was formerly referred to as fibrocystic breast disease. Some women also experience breast pain, tenderness, and lumpiness, especially in the upper, outer areas of the breasts, just before menstruation.[33]

Medical Terms Related to the Female Reproductive System

- Adnexa: Accessory structures of the uterus, such as the Fallopian tubes and ovaries.

- Amenorrhea: Absence of menstrual flow.

- Anovulation: Absence of ovulation.

- Dysmenorrhea: Painful menstrual flow.

- Dyspareunia: Painful sexual intercourse.

- Fistula: An abnormal passageway between two organs or an internal organ and the body surface. Although uncommon, a vaginal fistula can develop between the vagina and another organ, such as the urinary bladder, colon, or rectum.

- Mastitis: Inflammation of the breast that tends to occur when a woman is lactating.

- Menorrhagia: Excessive menstrual bleeding.

- Menometrorrhagia: Excessive and prolonged uterine bleeding occurring at irregular and/or frequent intervals.

- Metrorrhagia: Bleeding from the uterus between menstrual periods.

- Oligomenorrhea: Infrequent or very light menstruation.

- Polymenorrhea: Frequent menstruation in which menstrual cycles are shorter than 21 days.

Common disorders of the female reproductive system are discussed in the “Female Reproductive System Disorders” section.

Physiology of the Female Reproductive System

Menstruation, also called menses and commonly referred to as a woman’s “period,” is vaginal bleeding that occurs as part of a monthly cycle. Every month, the female body prepares for possible pregnancy by building up the endometrial tissue and ovulating. If no pregnancy occurs, the uterus sheds the endometrial lining. Menstrual flow is part blood and part endometrial lining that passes out of the uterus, through the cervix, and into the vagina. Menstruation typically starts in females between the ages of 12 and 14, referred to as menarche, and continues until menopause.[34]

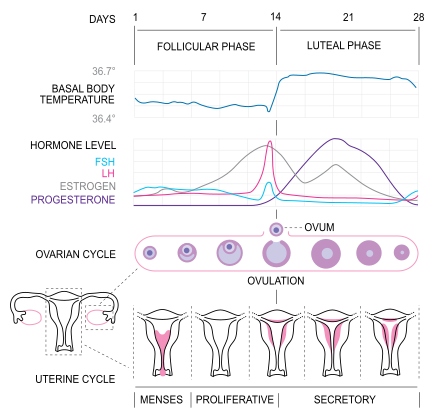

The Menstrual Cycle

The menstrual cycle is driven by a monthly hormonal cycle as the female’s body prepares an egg for fertilization and possible pregnancy. The menstrual cycle is counted from the first day of bleeding of one cycle to the first day of the next menstrual cycle. Menstrual flow usually lasts about three to five days. The typical volume of blood lost during menstruation is approximately 30 milliliters (mL). Amounts greater than 80 mL, menstrual flow longer than five days, or bleeding between cycles can be symptoms of a disorder.[35]

The average menstrual cycle takes about 28 days and occurs in three phases, called the follicular, ovulatory, and luteal phases, also referred to as menses, proliferative, and secretory uterine cycles. Hormone levels change throughout the menstrual cycle. See Figure 8.7[36] for an illustration of the phases of the menstrual cycle.

Follicular Phase

The follicular phase, also referred to as the pre-ovulatory or proliferative phase, begins when menstrual flow ceases and the endometrium in the uterus begins to thicken. During the follicular phase of the menstrual cycle, the following events occur[37]:

- Two hormones, follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) and luteinizing hormone (LH), are released from the brain and travel in the blood to the ovaries. These hormones stimulate the growth of ova (eggs) in their own shells called follicles.

- The FSH and LH hormones also trigger an increase in the production of the hormone estrogen, which is produced by the developing follicles. As the estrogen level continues to rise, it turns off the production of FSH, like a switch. This careful balance of hormones allows the body to limit the number of follicles to be released. Estrogen also causes the endometrium (lining of the uterus) to develop in preparation for possible pregnancy during the ovulation phase.

- As the follicular phase progresses, one follicle in one ovary becomes dominant and continues to mature. This dominant follicle, called the Graafian follicle, suppresses the growth of all other follicles. In addition, this dominant follicle continues to produce estrogen.

Ovulatory Phase

The ovulatory phase usually starts about 14 days after the follicular phase begins. During this phase, the following events occur[38]:

- The rise in estrogen from the Graafian (dominant) follicle triggers a surge in the amount of luteinizing hormone (LH) produced by the brain. This surge causes the Graafian (dominant) follicle to release the ovum.

- When the ovum is released from the follicle, it is referred to as ovulation. The ovum is captured by the fimbriae, the finger-like projections on the end of the Fallopian tubes. The fimbriae sweep the egg into the Fallopian tube.

- For one to five days prior to ovulation, many women notice an increase in cervical mucus that looks like egg white. This mucus helps capture and nourish the sperm on the way to meet the egg for fertilization.

Luteal Phase

The luteal (postovulatory) phase begins right after ovulation and involves the following processes[39]:

- After the ovum is released, the empty follicle develops into a new structure called the corpus luteum. The corpus luteum is a temporary, hormone-producing gland involved in ovulation and early pregnancy.

- The corpus luteum secretes estrogen and progesterone. Progesterone prepares the uterus for implantation of a fertilized egg into the uterine lining and is an important hormone during pregnancy. Increased levels of progesterone also increase the woman’s basal body temperature, which is a key component used to track fertility.[40]

- If the egg becomes fertilized by sperm, which is referred to as conception, it is called an embryo. The embryo travels through the Fallopian tubes and implants in the endometrial lining of the uterus.

- If the egg isn’t fertilized, it dissolves in the uterus, the endometrial lining breaks down and sheds because it is no longer needed, and menses (bleeding) begins. This is also referred to as the menses or menstrual phase and lasts between two and seven days. See Figure 8.8[41] for an illustration of the progression of a follicle to a corpus luteum.

View a supplementary MedLine video[42] on ovulation: Ovulation Video.

- Gurung, P., Yetiskul, E., & Jialal, I. (2023). Physiology, male reproductive system. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK538429/ ↵

- “Figure_28_01_01.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Figure_28_01_03.JPG” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “63e4c7b77be4e97c88b4c649fbd6c6472cf58466” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 4.0. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- A.D.A.M. (2024, March 31). Sperm release pathway [Video]. A.D.A.M. All rights reserved. https://ssl.adam.com/content.aspx?productid=117&pid=17&gid=000121&site=makatimed.adam.com&login=MAKA1603&category=videomain ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Silberman, M. (2023). Priapism. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK459178/ ↵

- “Vulva_Figure_28_02_02.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Figure_28_02_01.JPG” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Breast cancer basics. https://www.cdc.gov/breast-cancer/about/ ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Figure_28_02_09.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0. ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2023). Fibrocystic breasts. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/fibrocystic-breasts/symptoms-causes/syc-20350438 ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2013). Anatomy and physiology. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “MenstrualCycle2_en.svg.png” by Isometrik is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Female reproductive system. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/9118-female-reproductive-system ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Female reproductive system. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/9118-female-reproductive-system ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Female reproductive system. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/9118-female-reproductive-system ↵

- Steward, K., & Raja, A. (2023). Physiology, ovulation and basal body temperature. StatPearls [Internet]. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK546686/ ↵

- “Anatomy_and_physiology_of_animals_Ovarian_cycle_showing_from_top_left_clockwise.jpg” by Sunshineconnelly at English Wikibooks is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- A.D.A.M. (2022, January 10). Ovulation [Video]. Medline Plus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/anatomyvideos/000094.htm ↵

Male reproductive organs that produce sperm and testosterone.

A group of hormones, including testosterone, that play a role in male traits and reproductive activity.

The external sac that contains the testes in males, regulating the temperature for sperm production.

A condition in which one or both testicles fail to descend from the abdomen into the scrotum before birth.

A bundle of fibers and tissues that run from the abdomen to each testicle, containing blood vessels, nerves, and the vas deferens.

A medical condition where a testicle twists on the spermatic cord, cutting off blood supply and potentially causing damage if not treated promptly.

Occurs when an opening allows the bowel to extend into the scrotum.

An enlargement of veins within the scrotum, similar to varicose veins, which can affect fertility.

Tubes located within the testes where sperm production (spermatogenesis) takes place.

A long, coiled tube located behind each testicle, where sperm mature and are stored before ejaculation.

The duct that carries sperm from the epididymis to the urethra in preparation for ejaculation.

The fluid that carries sperm, produced by the prostate, seminal vesicles, and other glands in the male reproductive system.

Glands that produce a significant portion of the fluid that makes up semen, contributing nutrients and enzymes to support sperm.

A surgical procedure that involves cutting or sealing the vas deferens to prevent sperm from reaching the semen, effectively sterilizing the male.

A male gland that surrounds the urethra and produces fluid that is part of semen.

Glands in the male reproductive system that produce a fluid that helps lubricate the urethra for sperm to pass through during ejaculation.

The external male genital organ that serves as the conduit for urine and semen to exit the body.

Another term for sexual intercourse, where the penis is inserted into the vagina.

The rounded, sensitive tip of the penis.

A surgical procedure in which the foreskin, the layer of skin that covers the head of the penis, is removed.

The fold of skin that covers the glans of the penis, which can be removed during circumcision.

The foreskin in males covering the glans of the penis.

The primary male sex hormone responsible for the development of male secondary sex characteristics and reproductive functions.

The phase of development during which individuals undergo physical changes that lead to sexual maturity and reproductive capability.

Sexual drive or desire, influenced by biological, psychological, and social factors.

The process by which sperm are produced and matured in the testes.

The male reproductive cell, responsible for fertilizing the female egg (ovum).

The release of semen from the penis, typically during orgasm.

The peak of sexual pleasure, often accompanied by the release of tension and involuntary muscle contractions.

Painful or prolonged penile erections.

The external female genitalia, including the labia, clitoris, and vaginal opening.

The rounded area of fatty tissue over the pubic bone, covered with pubic hair after puberty.

The outer folds of skin surrounding the vaginal opening, providing protection to the internal reproductive organs.

The inner folds of skin located just inside the labia majora, which help protect the vaginal and urethral openings.

Erectile tissue that originates from the same fetal cells as the penis and has abundant nerves that are important in sexual sensation and orgasm.

Glands in the male reproductive system that produce a fluid that helps lubricate the urethra for sperm to pass through during ejaculation.

The area between the anus and the genitals in both males and females

The muscular canal in females that leads from the cervix to the outside of the body, playing a role in menstruation, sexual intercourse, and childbirth.

The female reproductive organ where a fertilized egg implants and grows into a fetus during pregnancy.

The lower, narrow part of the uterus that connects to the vagina and serves as a passage for menstrual blood, sperm, and childbirth.

The outermost layer of the uterus, consisting of a thin layer of epithelial cells.

The muscular layer of the uterus responsible for contractions during menstruation and childbirth.

The inner lining of the uterus that thickens during the menstrual cycle to prepare for a potential pregnancy. If fertilization does not occur, it is shed during menstruation.

A female reproductive organ that produces eggs (ova) and the hormones estrogen and progesterone.

Tubes that connect the ovaries to the uterus, through which an egg travels during ovulation. Fertilization of the egg by sperm typically occurs here.

Finger-like projections at the end of the fallopian tubes that help guide the egg from the ovary into the tube during ovulation.

The production and secretion of milk from the mammary glands, typically following childbirth.

Tubes that carry milk from the mammary glands to the nipple during breastfeeding.

A condition characterized by lumpy or rope-like breast tissue, often accompanied by discomfort or tenderness, usually related to hormonal changes.

The structures adjacent to an organ. In gynecology, it refers to the ovaries, fallopian tubes, and ligaments attached to the uterus.

The absence of menstruation. It can be primary (when menstruation never begins) or secondary (when menstruation stops after previously occurring).

The absence of ovulation, when the ovary does not release an egg during the menstrual cycle.

Painful menstruation that can be caused by underlying conditions like endometriosis or uterine fibroids.

Pain during sexual intercourse, which can have physical or psychological causes.

An abnormal connection between two body parts, such as between the rectum and vagina or the bladder and vagina, often resulting from injury, surgery, or infection.

Inflammation of breast tissue, often due to infection, commonly occurring during breastfeeding.

Abnormally heavy or prolonged menstrual bleeding.

Irregular or excessive bleeding during and between menstrual periods.

Irregular uterine bleeding that occurs between menstrual periods.

Infrequent or irregular menstrual periods, typically occurring more than 35 days apart.

A condition where menstrual cycles occur more frequently than normal, typically less than 21 days apart.

The monthly shedding of the endometrial lining of the uterus, resulting in blood flow through the vagina.

The first occurrence of menstruation in a female, marking the beginning of reproductive capability.

The first phase of the menstrual cycle, during which the follicles in the ovaries grow and prepare for ovulation.

A hormone produced by the pituitary gland that stimulates the growth of ovarian follicles in females and the production of sperm in males.

A hormone produced by the pituitary gland that triggers ovulation in females and stimulates testosterone production in males.

Small sacs in the ovaries that contain a developing egg. Each month, one follicle matures and releases an egg during ovulation.

A group of hormones primarily responsible for the development of female secondary sexual characteristics and the regulation of the menstrual cycle.

A mature egg cell released from the ovary, capable of being fertilized by sperm.

The release of a mature egg from the ovary into the fallopian tube, usually occurring around the middle of the menstrual cycle.

A temporary structure in the ovary that forms after ovulation and produces progesterone to support early pregnancy.

A hormone produced by the ovaries and placenta that helps prepare the endometrium for pregnancy and maintains early stages of gestation.

The process by which a fertilized egg attaches to the lining of the uterus, where it will continue to develop into an embryo.

The moment when a sperm fertilizes an egg, leading to the formation of an embryo.

An early stage of development in multicellular organisms. In humans, it refers to the first eight weeks after conception.