2.4 Secondary Prevention

Secondary prevention interventions focus on screening to identify early stages of disease, often before the client experiences signs or symptoms of the disease. Early detection allows for early treatment so clients can maintain the highest level of health possible.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) is an independent, volunteer panel of national experts that makes evidence-based recommendations about preventive services, including screening. The USPSTF systematically reviews evidence on preventive services, including the benefits and harms of preventive services, and makes recommendations.[1] In addition to USPSTF recommendations, other organizations make screening recommendations for specific conditions, such as the American Cancer Society. Clients should make decisions regarding screening in collaboration with their health care provider while considering the benefits of screening, in addition to the potential risks of additional unnecessary diagnostic testing that may occur.

Nurses should be familiar with current recommendations for health screenings and teach clients about these recommendations. Nurses also work with health care providers to conduct screenings and may be responsible for counseling clients about their results.

Read about current screening recommendations on the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force web page.

Screening for Adults, Children, and Adolescents

Some examples of preventative screening for adults, children, and adolescents include the following[2],[3]:

- Adults

- Alcohol and substance use disorder

- Blood pressure

- Bone density

- Cancer of the breast, cervix, prostate, and skin

- Cholesterol

- Depression

- Diabetes mellitus

- Fall risk

- HIV

- Sexually transmitted infection

- Tobacco use

- Adolescents[4]

- Height, weight, and body mass index

- Alcohol and drug use

- Anemia

- Anxiety

- Blood pressure

- Cervical abnormalities

- Cholesterol

- Depression

- Hearing

- Hepatitis B

- Sexually transmitted infections, including chlamydia, gonorrhea, and HIV

- Tuberculosis

- Vision

- Infants and Children[5],[6]

- Anxiety

- Autism

- Dental

- Depression

- Developmental delay

- Hearing

- Hepatitis B

- Newborn screening

- Vision

Read more about newborn screening in the “Applying the Nursing Process and Clinical Judgment Model to Newborn Care” section of the “Healthy Newborn” chapter.

Screening for Cancer

Nurses educate clients on the importance of screening for various types of cancers.

Breast Cancer

Breast cancer occurs when breast cells mutate and become cancerous cells that multiply and form tumors. There are different kinds of breast cancer, depending on which cells in the breast turn into cancer. Most breast cancers begin in the ducts (called invasive ductal carcinoma) or lobules (called invasive lobular carcinoma). There are also other kinds of breast cancer. Breast cancer can spread outside the breast to other parts of the body through blood and lymph vessels. When breast cancer spreads to other parts of the body, it is said to have metastasized.

People of both genders who have a strong family history of breast cancer or inherited changes in BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes have a high risk of getting breast cancer. Warning signs of breast cancer include the following[7]:

- New lump in the breast or armpit

- Thickening or swelling of part of the breast

- Irritation or dimpling of breast skin

- Redness or flaky skin in the nipple area or the breast

- Pulling in of the nipple or pain in the nipple area

- Nipple discharge other than breast milk, including blood

- Any change in the size or the shape of the breast

- Pain in any area of the breast

Nurses encourage clients to be aware of their bodies and report warning signs of breast cancer to their health care provider. However, according to the American Cancer Society, clinical and monthly self-breast exams are no longer recommended for breast cancer screening among average-risk women at any age.[8]

Mammogram

Nurses teach clients about the importance of mammogram screening. A mammogram is a radiographic image of breast tissue that can detect signs of cancer, often before a lump is felt. See Figure 2.7[9] for an image of a woman receiving a mammogram.

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that women aged 40 to 74 years old who are at average risk for breast cancer obtain a mammogram every two years. Mammography screening prior to age 40 should be an individual decision between a woman and her health care provider.[10]

Cervical Cancer

Cervical cancer is most often caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV). HPV is passed from one person to another during sexual contact. HPV causes cervical cells to change into abnormal cells (called dysplasia), which over time can become cancer. Cervical cancer is highly curable when found and treated early. Early cervical cancer does not cause symptoms, so routine PAP smears and HPV testing are recommended to screen for cancer.[11]

The Papanicolaou smear, commonly referred to as a PAP smear, is a cytological study that screens for cancer in the cervix before symptoms even occur. During a PAP smear, a health care provider inserts a speculum into the patient’s vagina to allow for visualization of the cervix and obtain samples of cervical cells for laboratory analysis. An HPV test is also typically performed during a PAP smear to check for infection with high-risk types of HPV that cause cancer.[12]

The CDC provides the following recommendations for cervical cancer screening[13]:

- Ages 21-29: First PAP smear at age 21; if normal, can typically be done every three years

- Ages 30-65: Several options are available, so patients should talk to their health care provider about what option is best for them:

- HPV test only: If normal, repeat screen every five years

- HPV along with Pap smear: If both normal, repeat screen every five years

- Pap smear only: If normal, repeat screen every three years

- Over 65: Additional screening may not be required if previous screenings were normal, so clients should discuss recommendations with their health care provider

- Clients who have had a hysterectomy that included removal of their cervix do not need a PAP or HPV if they have no history of cervical cancer or precancer[14]

Colorectal Cancer

Colon cancer is the third most common cancer diagnosed in people in the United States. It develops from polyps in the lining of the colon and typically affects people aged 45 years and older. Individuals can greatly reduce their risk for colon cancer by having regular screenings for polyps.[15]

Risk factors for colon cancer include a personal or family history of colon polyps or colon cancer and inflammatory bowel disease like Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Early symptoms of colon cancer include blood in the stool and persistent bowel changes like diarrhea and constipation. Colon cancer is diagnosed with biopsies taken during a colonoscopy.[16]

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that adults aged 45 to 75 be screened for colorectal cancer. The decision to be screened between ages 76 and 85 should be made on an individual basis between the client and their health care provider.[17]

There are several screening methods used to detect colon cancer. Clients should talk with their health care provider about the benefits and risks of each method, taking into account their personal risk factors for colorectal cancer. Nurses must be knowledgeable about different screening methods because they may be responsible for teaching the client how to accurately perform the test at home.

Several stool-based tests can be used to screen for polyps or colorectal cancer[18]:

- Guaiac-based Fecal Occult Blood Test (gFOBT): This test uses a chemical called guaiac to detect blood in the stool. For this test, the patient receives a test kit from their health care provider. At home, they use a small stick or brush to obtain a small amount of stool and place it on a card. The test kit is returned to a lab, where the stool sample is checked for the presence of blood. This test is being phased out due to increased use of in-home DNA testing.

- Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT): This test uses antibodies to detect blood in the stool.

- Stool DNA Test: This test combines the fecal immunochemical test with a test that detects altered DNA in the stool. For this test, an entire bowel movement is collected and sent to a lab, where it is checked for altered DNA and the presence of blood.

Stool-based methods are typically only recommended for people at low risk for colon cancer. If a stool-based test is positive, then a colonoscopy is scheduled for follow-up testing. See Figure 2.8[19] for an image of a stool specimen container commonly used in stool-based tests.

Other screening tests include visualization of the rectum and colon. During endoscopic procedures like flexible sigmoidoscopy and colonoscopy, if any polyps are found, they can be removed and biopsied. These tests include the following[20]:

- Flexible Sigmoidoscopy: During this test, a flexible tube is inserted into the rectum and the lower third of the colon. It is recommended every five years or every ten years if an annual Fecal Immunochemical Test (FIT test) is also performed.

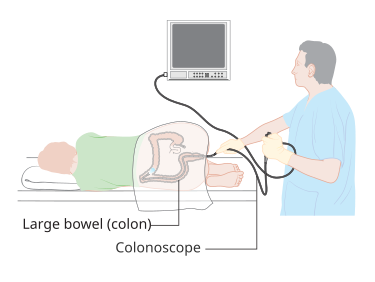

- Colonoscopy: This test is similar to a flexible sigmoidoscopy but visualizes the entire large intestine, including the colon, rectum, and anus. The U.S. Preventive Screening Task Force recommends if colonoscopy screening is used for adults aged 45 to 75 with an average risk for colon cancer, it should be performed every ten years.[21] See Figure 2.9[22] for an illustration of a colonoscopy.

- Computed Tomography (CT) Colonography: This test is also called a virtual colonoscopy. A CT scan produces images of the entire colon, and the images are displayed on a computer monitor for the health care provider to analyze. This test is recommended every five years.

Bowel Preparation

Visualization tests require preparation of the colon to ensure optimal visualization. Nurses teach clients how to perform the prescribed preparation at home or administer the bowel prep if the client is in a long-term or acute-care setting.

For outpatient procedures, bowel preparation requires the client to adjust their diet for a few days prior to the procedure. They are instructed to eat low-fiber foods (such as soups, eggs, rice, chicken, pasta) and to avoid high-fiber foods (such as nuts, seeds, popcorn, red meat, and raw vegetables) for several days before the test. On the day prior to the exam, a clear liquid diet is typically prescribed, along with avoidance of red liquids such as red gelatin or popsicles. The client is typically prescribed nothing by mouth (NPO) after midnight. Several hours before the procedure, an oral laxative is often taken to cleanse the bowel based on the provider’s prescription. Nurses should caution clients that although the bowel cleansing process can be uncomfortable with several trips to the restroom, it is important that the entire laxative formula is ingested so the colon can be optimally visualized during the exam. The goal of the bowel prep is for the client’s bowel movements to be liquid and clear. While the liquid stool may be yellow, it should not be cloudy. If the bowel preparation is not adequate, retained stool may interfere with the provider’s ability to see the internal structures accurately. Therefore, the client may require additional bowel cleansing prior to the procedure or it may be rescheduled.[23]

Lung Cancer

When cancer begins in the lungs, it is called lung cancer, although it may spread to lymph nodes or other organs in the body. Cancer from other organs also may spread to the lungs, which is referred to as metastasis.

Cigarette smoking is the number one risk factor for lung cancer. In the United States, cigarette smoking is linked to about 80% to 90% of lung cancer deaths. People who quit smoking at any age have a lower risk of lung cancer than if they had continued to smoke, but their risk is higher than the risk for people who never smoked.[24]

After smoking, radon is the second leading cause of lung cancer in the United States. Radon is a naturally occurring gas that forms in rocks, soil, and water. It cannot be seen, tasted, or smelled. When radon gets into homes or buildings through cracks or holes, it can get trapped and build up in the air inside. People who live or work in these homes and buildings breathe in high radon levels. Over long periods of time, radon can cause lung cancer.

Most people with lung cancer don’t have symptoms until the cancer is advanced and has metastasized. Lung cancer symptoms may include the following[25]:

- Coughing that gets worse or doesn’t go away

- Chest pain

- Shortness of breath

- Wheezing

- Hemoptysis (coughing up blood)

- Fatigue (feeling very tired all the time)

- Weight loss with no known cause

- Repeated episodes of pneumonia

- Swollen or enlarged lymph nodes inside the chest in the area between the lungs

Lung cancer may initially be suspected after routine tests like chest X-rays show abnormal results. Additional diagnostic testing such as a CT scan is performed if lung cancer is suspected.

Recommendations for lung cancer screening are based on the smoking history of the client. A pack-year is defined as smoking one pack of cigarettes a day for a year. Given that definition, a client who smoked one pack a day for 20 years would be considered to have a 20 pack-year history, as would a client who smoked two packs a day for 10 years. The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends yearly lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography (CT) for people who have a 20 pack-year or more smoking history and smoke now or have quit within the past 15 years and are between 50 and 80 years old. Lung cancer screening comes with its own risks, such as false-positive results, overdiagnosis, and radiation exposure, so only high-risk clients are screened.[26]

Nurses must gather accurate data from the client regarding their smoking history so that primary and secondary prevention interventions can be appropriately applied. Nurses provide primary prevention for clients who smoke by teaching about the benefits of smoking cessation. Additionally, nurses provide secondary prevention by encouraging lung cancer screening for those at high risk of cancer development. Furthermore, clients at risk for radon exposure in their home are encouraged to perform radon testing and radon mitigation if radon test results are above the recommended threshold.

Skin Cancer

Skin cancer is common, with one in five Americans experiencing some type of skin cancer in their lifetime. Basal cell carcinoma is the most common of all cancers that occur in the United States and is frequently found on areas most susceptible to long-term sun exposure such as the head, neck, arms, and back. Basal cell carcinomas start in the epidermis and become an uneven patch, bump, growth, or scar on the skin surface. Basal cell carcinoma rarely metastasizes. Squamous cell carcinoma presents as lesions commonly found on the scalp, ears, and hands. If not removed, squamous cell carcinomas can metastasize to other parts of the body.[27] See Figure 2.10[28] for an image of squamous cell carcinoma.

Melanoma is skin cancer caused by the uncontrolled growth of melanocytes, the pigment-producing cells in the epidermis. Melanoma commonly develops from an existing mole that becomes abnormal. A mole is a small, dark, benign skin growth. Melanoma is the most fatal of all skin cancers because it is highly metastatic and can be difficult to detect before it has spread to other organs.[29] See Figure 2.11[30] for an image of a melanoma.

Although there are no current guidelines for screening tests for skin cancer from the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force, annual skin checks by a dermatologist are recommended, especially if the client has a history of benign skin cancer or moles that frequently change in size. Nurses provide primary prevention by encouraging the use of sunscreen and teaching clients how to use the “ABCDE” criteria for detecting changes in moles that may indicate early melanoma[31]:

- Asymmetry: The shape of one half does not match the other half.

- Border: The border is irregular, meaning the edges are ragged, notched, or blurred. The pigment may spread into the surrounding skin.

- Color: There is uneven color with different shades of black, brown, and tan. Areas of white, gray, red, pink, or blue may also be seen.

- Diameter: There is an increased change in the size of the mole. Most melanomas are larger than six millimeters wide (about 1/4 inch).

- Evolving: The mole has changed over the past few weeks or months.

Clients are advised to schedule an appointment with their primary health care provider or dermatologist if suspicious moles are identified.

Other Cancers

The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force has reviewed the evidence of other cancer screenings and determined there is no reduction in cancer deaths when performing routine screening for oral, ovarian, pancreatic, prostate, bladder, testicular, or thyroid cancers. For example, in men aged 55 to 69 years, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force recommends that the decision to undergo periodic prostate-specific antigen (PSA)-based screening for prostate cancer should be an individual one. Before deciding whether to be screened, men should have an opportunity to discuss the potential benefits and harms of screening with their clinician and to incorporate their values and preferences in the decision. Nurses teach clients to report concerning symptoms to their health care providers.

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (n.d.). Home page. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/ ↵

- Healthcare.gov. (n.d.). Preventative care benefits for adults. https://www.healthcare.gov/preventive-care-adults/ ↵

- Healthcare.gov. (n.d.). Preventative care benefits for children. https://www.healthcare.gov/preventive-care-children/ ↵

- U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. (n.d.). Recommended clinical preventive services for adolescents. https://opa.hhs.gov/adolescent-health/physical-health-developing-adolescents/clinical-preventive-services/recommended ↵

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2017). Vision in children ages 6 months to 5 years: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/vision-in-children-ages-6-months-to-5-years-screening ↵

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2022). Anxiety in children and adolescents: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/screening-anxiety-children-adolescents ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). What is breast cancer? https://www.cdc.gov/breast-cancer/about/ ↵

- American Cancer Society. (2023). American Cancer Society recommendations for the early detection of breast cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/breast-cancer/screening-tests-and-early-detection/american-cancer-society-recommendations-for-the-early-detection-of-breast-cancer.html ↵

- “Woman_receives_mammogram.jpg” by Rhoda Baer is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2024). Recommendation: Breast cancer: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/breast-cancer-screening ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2021). Understanding cervical changes: A health guide. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/patient-education/understanding-cervical-changes ↵

- National Cancer Institute. (2021). Understanding cervical changes: A health guide. National Institutes of Health. https://www.cancer.gov/publications/patient-education/understanding-cervical-changes ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). What should I know about screening? https://www.cdc.gov/cancer/cervical/basic_info/screening.htm ↵

- American Cancer Society. (2021). The American Cancer Society guidelines for the prevention and early detection of cervical cancer. https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/cervical-cancer/detection-diagnosis-staging/cervical-cancer-screening-guidelines.html ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Colorectal (colon) cancer. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/14501-colorectal-colon-cancer ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Colorectal (colon) cancer. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/14501-colorectal-colon-cancer ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). What should I know about screening? https://www.cdc.gov/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). What should I know about screening? https://www.cdc.gov/ ↵

- “Stool_specimen_container.jpg” by Whispyhistory is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). What should I know about screening? https://www.cdc.gov/ ↵

- U.S. Preventive Services Task Force. (2021). Recommendation: Colon cancer: Screening. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/recommendation/colorectal-cancer-screening ↵

- “Diagram_showing_a_colonoscopy_CRUK_060.svg” by Cancer Research UK. Wikimedia Commons is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0 ↵

- Cleveland Clinic. (2022). Colonoscopy prep. https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/treatments/22657-colonoscopy-bowel-preparation ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). What is lung cancer? https://www.cdc.gov/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). What is lung cancer? https://www.cdc.gov/ ↵

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023). Who should be screened for lung cancer? https://www.cdc.gov/ ↵

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. (n.d.). Types of skin cancer. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/skin-cancer/types/common ↵

- “Squamous cell carcinoma (3).jpg” by unknown photographer, provided by National Cancer Institute is licensed under CC0 ↵

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. (n.d.). Types of skin cancer. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/skin-cancer/types/common ↵

- “Melanoma (2).jpg” by unknown photographer, provided by National Cancer Institute is in the Public Domain. ↵

- American Academy of Dermatology Association. (n.d.). Types of skin cancer. https://www.aad.org/public/diseases/skin-cancer/types/common ↵

Early detection of disease.

An independent, volunteer panel of national experts that makes evidence-based recommendations about preventive services including screening.

When breast cells mutate and become cancerous cells that multiply and form tumors.

A radiographic image of breast tissue that can detect signs of cancer, often before a lump is felt.

Caused by the human papillomavirus (HPV).

Develops from polyps in the lining of the colon and typically affects people aged 45 years and older.

Test uses a chemical called guaiac to detect blood in the stool.

Test uses antibodies to detect blood in the stool.

Test combines the fecal immunochemical test with a test that detects altered DNA in the stool.

A flexible tube is inserted into the rectum and the lower third of the colon.

Similar to a flexible sigmoidoscopy but visualizes the entire large intestine, including the colon, rectum, and anus.

A CT scan produces images of the entire colon, and the images are displayed on a computer monitor for the health care provider to analyze.

The spread of cancer cells from the place where they first formed to another part of the body.

Smoking one pack of cigarettes a day for a year.

Skin cancer caused by the uncontrolled growth of melanocytes, the pigment-producing cells in the epidermis.