Chapter 8: The Power of Play: Enhancing Developmentally Appropriate Practice in Early Childhood Education

Sara Horstman, BS

Course Competency: Examine the critical role of play as it relates to developmentally appropriate practice

Learning Objectives:

- Describe the importance of play

- Identify the types and stages of play

- Identify the educator’s role in preparing the environment and facilitating play

- Describe how hands-on, play-based experiences promote child development/learning in all domains

- Identify the educator’s role in using observational skills to support play and learning

8.1 Introduction

Play is the foundation of early childhood development, serving as both a natural and essential way for children to explore, learn, and grow. Through play, children develop critical cognitive, social, emotional, and physical skills that shape their overall well-being. This chapter will explore the importance of play in early childhood education (ECE) and examine the various types and stages of play that support developmentally appropriate practice. Additionally, it will highlight the essential role of educators and caregivers in creating environments that foster meaningful play experiences, using observation to guide and support learning. By understanding how hands-on, play-based experiences promote growth across all developmental domains, educators can ensure that play remains at the heart of early learning.

8.2 Importance of Play

Children are born observers. From infancy, they watch, listen, and explore their surroundings to make sense of the world. Today’s children are not passive recipients of adult knowledge—they are active participants in their own learning. Being an observer not only helps children gather information but also fosters curiosity, initiative, and problem-solving skills. Even the youngest child learns through watching others, experimenting with materials, and drawing conclusions based on what they see and experience.

As you have read previously, developmentally appropriate practice (DAP) challenges early childhood professionals to be intentional in how they design environments and engage with children to support meaningful learning. Under the umbrella of DAP, knowledge is constructed through active learning, and discovery is made possible through rich opportunities for exploration. When educators recognize and support children’s natural capacity to observe, they empower children to build understanding in a way that is authentic and developmentally meaningful—laying the foundation for lifelong learning.

Play is important. The following are key reasons why play should be incorporated into the curriculum and classroom:

- Inspires imagination

- Facilitates creativity

- Fosters problem-solving

- Promotes development of new skills

- Builds confidence and high levels of self-esteem

- Allows free exploration of the environment

- Fosters learning through hands-on and sensory exploration

It is now recognized that what is often dismissed as “just play” is actually a powerful form of active learning. Through play, children explore the properties of materials and discover how they can be used, changed, or represented. They experiment with different ways of interacting with objects, which helps them develop and refine concepts and ideas. This hands-on exploration of the world—both social and physical—begins at birth and continues to shape their understanding and development.

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ young child playing with wooden blocks](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/67/2025/03/aitubo-81.jpg)

View the following YouTube video from the Wisconsin Department of Education about the importance of play: Play is the Way

Reflect

- What do you remember about playing as a child?

- Where was your favorite place to play? People to play with? Items to play with?

8.3 Piaget’s Stages of Play and How Children Play

Educators observe stages of play, described in Table 8a, through the experiences children navigate in their program. Drawing from Piaget’s theory of cognitive development, these stages of play reflect how children construct knowledge through active exploration and interaction with their environment (California Department of Education, 2016). Educators use these observations to better understand each child’s developmental stage, plan environments, set individualized goals, and design meaningful, developmentally appropriate curricular experiences.

| Stage | Description |

|---|---|

| Functional Play (Birth–2 Years) | Exploring, inspecting, and learning through repetitive physical activity |

| Symbolic Play (Around 2–7 Years) | The ability to use objects, actions, or ideas to represent other objects, actions, or ideas and may include taking on roles (Picture Perfect Playgrounds, Inc., 2025c) |

| Constructive Play (Around 2–7 Years) | Involves experimenting with objects to build things; learning things that were previously unknown with hands-on manipulation of materials (Picture Perfect Playgrounds, Inc., 2025a) |

| Games With Rules (Around 7 Years and Older) | Imposes rules that must be followed by everyone who is playing; the logic and order involved form the foundations for developing game playing strategies (Picture Perfect Playgrounds, Inc., 2025b) |

In the world of ECE, there are not only observable stages of play but also types of play done by children 0–8 years old. Mildred Parten (1933), a sociologist and researcher best known for her pioneering work on children’s social play, observed 2–5-year-old children and noted six types of play. Three types she labeled as nonsocial (unoccupied, solitary, and onlooker), and three types were categorized as social play (parallel, associative, and cooperative). Table 8b describes each play type. Young children tend to engage in the nonsocial play more than the older children; by age 5, associative and cooperative play are the most common forms of play (Dyer & Moneta, 2006).

| Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Unoccupied Play | Children’s behavior seems more random and without a specific goal. This is the least common form of play. |

| Solitary Play | Children play by themselves, do not interact with others, and do not engage in similar activities as the children around them. |

| Onlooker Play | Children are observing other children playing. They may comment on the activities and even make suggestions but will not directly join in the play. |

| Parallel Play | Children play alongside each other, using similar toys, but do not directly interact with each other. |

| Associative Play | Children will interact with each other and share toys but not work together toward a common goal. |

| Cooperative Play | Children are interacting to achieve a common goal. Children may take on different tasks to reach that goal. |

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ Several young children are interacting with colored beads on a table](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/67/2025/03/aitubo-68.jpg)

Please note that, very much like the Wisconsin Model Early Learning Standards (WMELS), the types of play are not age-marked. The ways children play is dependent on them as an individual, their culture, and their environment. This is why it is important to observe and meet the child where they are at in their exploration of play.

Reflect

- Which stages of play have you observed with children?

- What events or interactions helped you categorize this stage?

8.4 Facilitating Play

A facilitator’s role is to set the stage (the environment) and then provide both time and opportunities for the children to explore and play. According to Lisa Murphy (2016), trainer and founder of Ooey Gooey, Inc., children and adults have two different definitions of play. Play to an adult has a tangible outcome at the end such as finishing a book or sewing a dress, but to children there is no observable goal or outcome. Being a facilitator of play means that you are ready and willing to assist when called upon. This should not be confused with not doing anything while the children play, during free play. Instead, this means having developmentally appropriate materials readily available for the children to explore their environment. It also means accepting that children will get messy, some of your materials will not clean up as perfectly as they did right out of the box, and the items might be played with in a different way than intended. Children’s play thrives when adults step back and relinquish some control. Allowing children more autonomy is key to facilitating authentic play experiences. To foster genuine play, adults need to be willing to let children take the lead.

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. (April 28 version) [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/ An educator is setting up their preschool classroom](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/67/2025/03/ChatGPT-Image-Jun-27-2025-11_11_01-AM.png)

When educators regularly observe and document brief, subtle moments of children’s learning through play, those records can help parents and others understand how useful and important play is in helping children to learn and grow. For example, an educator might report the following about a child’s language and social development to the parent of a 3-year-old:

“I watched Sarah standing outside the playhouse area today. Instead of just watching the other children or wandering through their play without getting involved as she often does, she brought the children a book to read to the ‘baby’ in the family. They asked her if she wanted to be the big sister, and she said ‘Yes’ and joined right in. I have been thinking about ways to help her learn how to use her language to get involved in play with other children, but she figured out her own, creative way to join them.”

In early childhood settings, the structure and leadership of play experiences vary widely—from open-ended child-led exploration, to more structured, adult-led activities. Each type of play in Table 8c offers unique opportunities for learning. Understanding the differences can help educators make intentional choices that balance guidance with independence (Grounds for Play, 2025).

| Type of Play | Definition | Example | Purpose |

|---|---|---|---|

| Free Play | Unstructured, spontaneous play initiated and controlled by the child without specific goals set by an adult | A child chooses to build a tower with blocks during open center time, with no adult prompting or direction | Supports creativity, independence, decision making, and social interaction |

| Child-Directed Play | Play that is led by the child’s interests and choices but may take place in an environment thoughtfully prepared by an adult | An educator sets up a dramatic play center with dress-up clothes and props, and children choose roles and scenarios on their own | Encourages initiative, problem-solving, and leadership while still offering developmental supports through the materials provided |

| Adult-Guided Play | Play in which adults participate as partners or facilitators, gently guiding the direction without taking control | During a sensory bin activity, the educator engages with children by asking open-ended questions like, “What does that feel like?” or “Can you find something that makes a sound?” | Expands language, supports deeper thinking, and extends learning while honoring children’s lead |

| Adult-Directed Play | Structured activities planned and led by adults, often with a specific learning goal in mind | An educator leads a small group in a sorting game where children categorize objects by color or shape | Introduces new concepts, reinforces skills, and allows observation of developmental progress |

High-quality programs include a balance of these types of play throughout the day. Free and child-directed play promote independence and creativity, while adult-guided and adult-directed activities can scaffold learning and introduce new skills. Games help children practice social rules and regulation in a fun, engaging way.

By intentionally planning for a range of play experiences, educators can meet developmental goals while honoring the natural ways children learn best—through joyful, active exploration.

8.5 The Role of Play in Children’s Learning and Development

Scenario

Imagine four young children—eager and engaged in play amidst an assortment of wooden blocks. They may appear to be “just playing;” however, upon closer inspection, this moment of play reveals a web of ideas, theories, and hypotheses under construction, as well as an energetic debate. We may observe that the children are negotiating how to connect the blocks to make roads that will surround their carefully balanced block structure. The structure has walls of equal height, which support a flat roof, from which rise ten towers, built using cardboard tubes. Resting on each tube is a shiny, recycled jar lid, each one a different color. Two children are figuring out between themselves when to add or take away blocks in order to make a row of towers that increase in height. As we listen and watch, we witness the children building a foundation for addition and subtraction. To make each wall just high enough to support a flat roof, they count aloud the number of blocks they are using to make each wall, showing an emerging understanding of the math concept of cardinal numbers. When they hear the signal that lunch is about to be served, one child finds a clipboard with pen and paper attached, draws a rudimentary outline of the block structure on the paper, and then asks the teacher to write, “Do not mess up. We are still working on our towers.”

In this scenario, children show evidence of emerging concepts of social studies through their construction of a small community from blocks; of physical science and mathematics as they experiment with how to make objects balance; and of reading, writing, and drawing as they request the educator’s help with making a sign to protect their work. They work together to create their play and cooperate in carrying out agreed-upon plans. Each is fully engaged and manages their behavior to cooperate in a complex social situation. The concepts under construction in the minds of these children and the skills they are learning and practicing closely match several desired learning outcomes for children at this age. Anticipating the variety of concepts and skills that would emerge during the play, the teachers stocked the blocks/construction area with collections of blocks, props, and writing materials to support a full range of possibilities.

Because imaginary play holds such rich potential for promoting children’s cognitive, linguistic, social, and physical development, high-quality preschool programs recognize play as a key element of the curriculum. Children’s spontaneous play is a window into their ideas and feelings about the world. As such, it is a rich source of ideas for curriculum planning (Lockett, 2004). For example, if an educator observes a group of children repeatedly engaging in imaginary play about illness or hospitalization, they might decide to convert the playhouse area into a veterinary clinic for a week or two. The educator might also read children stories involving doctors, hospitals, getting sick, and getting well. The educator’s observations of children’s resulting conversations and activities would suggest ways to deepen or extend the curriculum further. In thinking of ways to extend the curriculum, it will be important that educators ensure that the materials used and themes built upon are culturally familiar to the children and value children’s cultural heritage (Learneo, Inc., n.d.).

8.6 The Teaching Cycle

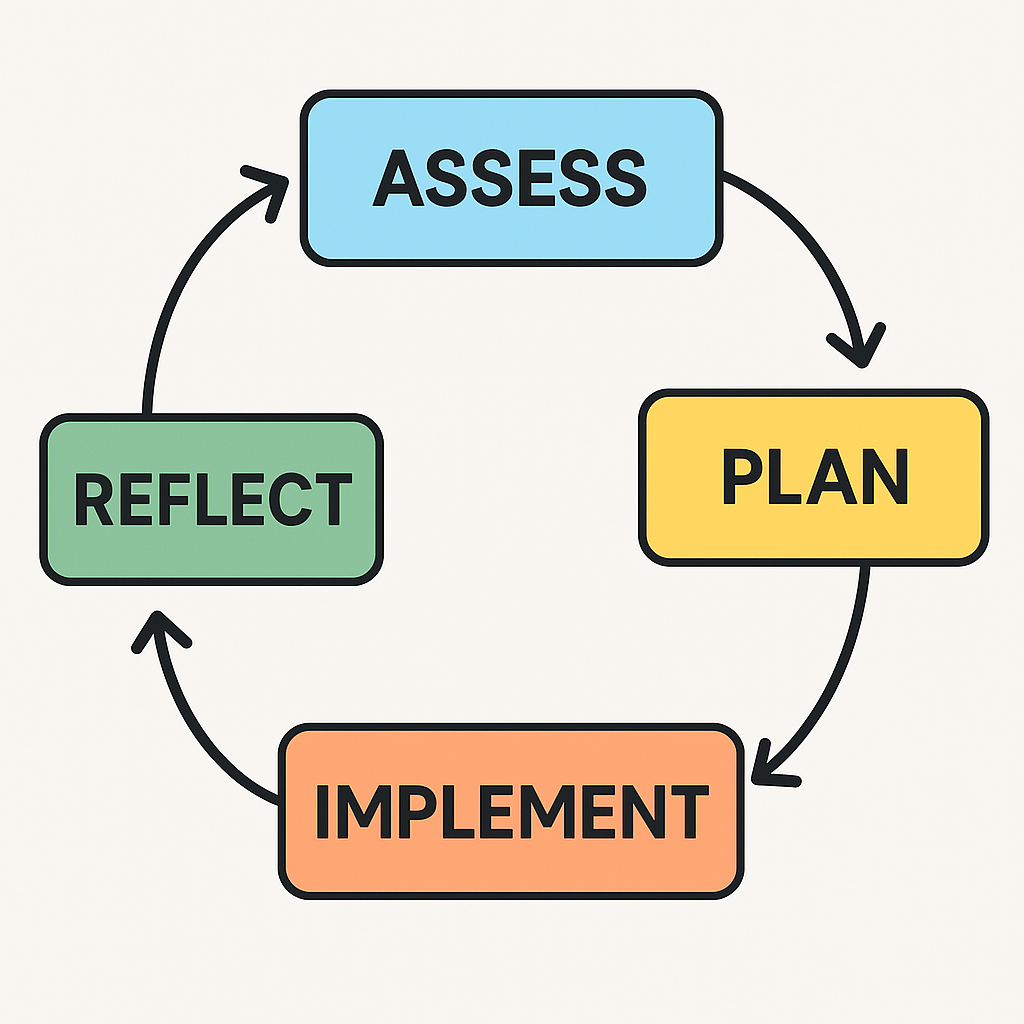

In ECE, the teaching cycle is a continuous, dynamic process that guides intentional and responsive teaching. At the heart of this cycle is assessment, which serves as the foundation for effective planning. By observing and assessing children’s development, interests, and learning styles, educators gather valuable insights that inform the next steps in instruction. These observations allow teachers to design meaningful, developmentally appropriate experiences that meet each child where they are. Rather than following a rigid curriculum, the teaching cycle empowers educators to adapt and respond—using assessment not just to monitor progress, but to plan experiences that foster deeper engagement, support individual needs, and promote holistic growth. Through this cycle of “Assess,” “Plan,” “Implement,” and “Reflect,” educators create an environment where every child can thrive.

Assessment in ECE is a systematic process of gathering, interpreting, and using information about children’s learning and development to make informed decisions that support their growth. Observation serves as a primary method for collecting meaningful data about children’s behaviors, skills, and interactions in natural contexts. Assessment serves multiple purposes. First, it helps educators monitor children’s progress toward developmental goals. Second, it helps identify individual learning needs, plan appropriate interventions, evaluate the effectiveness of teaching strategies and curriculum, and communicate progress to families and other professionals. Finally, it also informs decisions about transitions and future learning experiences.

The interconnection between observation and assessment is essential—systematic observation provides the raw data that helps educators identify what children know and can do, how they learn, and how they are progressing developmentally. This intentional approach allows educators to plan responsive and individualized learning experiences rooted in real understanding.

Observation in ECE is the intentional and systematic practice of watching, listening, and documenting children’s behaviors, interactions, and learning processes in their natural settings. It involves being fully present and attentive as children engage in play and interact with peers and their environment—without directing or participating in their activities. This kind of mindful presence, whether for a brief moment or a longer period, allows educators to truly see what unfolds in children’s play and learning. Through careful observation, educators can better understand each child’s unique strengths, interests, and learning styles. It also provides valuable insight into developmental milestones, social-emotional growth, communication skills, and problem-solving abilities. These observations serve as a foundation for responsive curriculum planning, help identify areas where additional support may be needed, and foster meaningful relationships by showing genuine interest in the child’s experiences. Additionally, documentation from observations supports communication with families, offering a window into their child’s progress and daily life in the classroom.

There are various observation and assessment methods described in Table 8d.

| Method | Description |

|---|---|

| Anecdotal Records | Brief notes describing specific incidents or behaviors |

| Running Records | Detailed, sequential accounts of everything a child says and does during a specific time |

| Time Sampling | Observing and recording specific behaviors at predetermined intervals |

| Event Sampling | Observing and recording every instance of a specific behavior |

| Checklists and Rating Scales | Using predetermined lists of skills or behaviors to mark presence or frequency |

| Learning Stories | Narrative observations that focus on a child’s learning process, highlighting their strengths and dispositions |

| Photographs and Videos | Capturing visual evidence of children’s learning and development |

| Work Samples | Collecting children’s drawings, writings, and creations to analyze their progress |

Early childhood educators see and support children as researchers, investigators, and experts and thus design the play environment to serve the children’s inquisitive minds. Educators also provide the materials children need to construct concepts and ideas and master skills in the natural context of play. Children learn from opportunities to discover materials that they may be seeing for the first time and need time to explore and get to know the properties of these materials. It means offering children materials that they can organize into relationships of size, shape, number, function, and time. Children can investigate what happens when they put these materials together or arrange them in new ways, experiencing the delight of discovering possibilities for building with them, transforming them, or using them to represent an experience.

8.7 Hands-on Learning Developing in All Areas

Hands-on learning uniquely allows children to gain knowledge of the topic or idea they are learning through experience.

Dr. Jody Sherman LeVos (2024) states that there are seven benefits to hands-on learning for children of all ages:

- Encourages Interaction to Improve Skills: Learning by doing is a great way to help children practice the skills that they have just learned. The key to hands-on learning is the engagement aspect with the content.

- Makes Abstract Concepts Concrete: When a child commits something to memory, such as counting numbers, it does not necessarily mean that they understand what they are doing or the concept. However, when they physically hold objects they are counting, they begin to understand. By using hands-on learning, children are able to connect what they are learning in the world around them.

- Strengthens Fine Motor Skills: Experiential learning (hands-on learning) encourages children to work on their fine motor skills, also known as the small muscles in your hands and fingers that help perform precise movements. These are movements and skills that will be used into adulthood

- Allows for Creativity: Hands-on learning creates opportunities for children to use all different types of creativity, not just in arts or music but also in their critical thinking skills when finishing a hands-on learning science experiment.

- Promotes Problem-Solving Skills: When children can figure things out on their own and think critically, they are allowing for different perspectives and different approaches to come up with solutions. Children face challenges when engaging in hands-on activities and can use trial and error to come up with solutions.

- Builds Social Skills: Hands-on experiences often involve group work or collaboration. Children practice communication skills, compromise, and conflict resolution when working hands-on as a group.

- Sparks Curiosity: When working hands-on with materials, children are often inspired to explore and ask questions. Children start to engage with the world around them and become active participants in their learning.

8.8 Conclusion

In conclusion, play is not merely a pastime for young children but rather a critical cornerstone of developmentally appropriate practice. It serves as the primary vehicle through which children explore their world; develop essential cognitive, social-emotional, physical, and language skills; and build a foundation for future learning. By recognizing and actively fostering child-led, engaging, and meaningful play experiences, educators align with developmentally appropriate principles, creating environments where children thrive, learn authentically, and reach their full potential. Embracing play as a fundamental element of ECE is, therefore, paramount to nurturing well-rounded, curious, and capable young learners.

8.9 Learning Activities

8.10 References

Grounds for Play. (2025). Cognitive and social types of play. https://groundsforplay.com/blog/cognitive-and-social-types-of-play

California Department of Education. (2016). Best practices for planning curriculum for young children [PDF]. https://www.cde.ca.gov/sp/cd/re/documents/intnatureoflearning2016.pdf

Dyer, J. L., & Moneta, G. (2006). Play and child development. Pearson.

Learneo, Inc. (n.d.). Lifespan Development Module 5: Early Childhood – Introduction to Early Childhood. Course Hero. https://courses.lumenlearning.com/lifespandevelopment2/chapter/module/

LeVos, J. S. (2024). 7 key benefits of hands-on learning (+5 engaging ideas). Begin Learning. https://www.beginlearning.com/parent-resources/hands-on-learning/#:~:text=Hands%2Don%20learning%20uniquely%20allows,something%20or%20solve%20a%20problem

Lockett, A. (2004). The continuous curriculum: Planning for spontaneous play. Kirklees Children & Young People Service Learning.

Murphy, L. (2016). Lisa Murphy on play: The foundation of children’s learning. Redleaf Press.

Parten, M. B. (1933). Social play among preschool children. Journal of Abnormal and Social Psychology, 28(3), 136-147.

Picture Perfect Playgrounds, Inc. (2025a). Constructive play. Play and Playground Encyclopedia. https://www.pgpedia.com/c/constructive-play

Picture Perfect Playgrounds, Inc. (2025b). Games and rules. Play and Playground Encyclopedia. https://www.pgpedia.com/g/games-rules

Picture Perfect Playgrounds, Inc. (2025c). Symbolic play. Play and Playground encyclopedia. https://www.pgpedia.com/s/symbolic-play

Images:

Figure 8a: Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/

Figure 8b: Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/

Figure 8c: OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. (April 28 version) [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/

Figure 8d: “the teaching cycle” by Nic Ashman, Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Videos:

Wisconsin. (2017, April 18). Play is the way [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=sbHwOzAO8to&t=108s