Chapter 1: Exploring Family: Structures, Trends, and Influences on Child Development

Toshiba L. Adams, PhD and Sara Horstman

Course Competency: Analyze family patterns and trends.

Learning Objectives:

- Develop a definition of family that is inclusive and diverse.

- Explore various family structures (e.g., nuclear family, one-parent family, foster family, gender-diverse parents).

- Describe trends affecting families.

- Analyze circumstances in families’ lives that influence child and family members’ actions.

- Explore literature and classroom resources related to diverse family patterns and trends.

1.1 Introduction

The concept of family is both deeply personal and profoundly social. Families exist in a rich array of forms, shaped by culture, history, socioeconomic factors, and personal experiences. Across the globe—and even within a single community—the definition of family continues to evolve. For some, family is defined by blood relations or legal ties; for others, it is grounded in emotional bonds, mutual care, and chosen connections. In the context of early childhood education, understanding what constitutes a family is essential. Educators and caregivers must be equipped to recognize and support a wide range of family structures, including nuclear families, single-parent households, blended families, multigenerational families, foster families, and families with gender-diverse parents. Each of these family forms carries its own strengths, traditions, and challenges, all of which influence the day-to-day experiences and development of children.

This chapter explores the inclusive and ever-evolving nature of families. A broad, respectful definition of family is developed—one that embraces the diversity found in today’s communities. Current social, economic, and cultural trends shaping family life are examined, including shifting marriage patterns, increased mobility, financial pressures, and changing gender roles. The chapter analyzes how life circumstances such as employment, housing, immigration, health, and access to resources influence the decisions, behaviors, and well-being of family members. By the end of the chapter, a deeper understanding of the important and complex role families play in a child’s life is gained—along with practical strategies to support and honor that diversity in educational settings.

1.2 What Is a Family?

According to the Blackwell Encyclopedia of Sociology, the definition of “family diversity” refers to a “broad range of characteristics or dimensions on which families vary, along with a recognition that many different family types function effectively” (Van Eeden-Moorefield & Demo, 2007). This statement highlights the outdated assumption that only one type of family is ideal, and all others are dysfunctional and deviant. As our world and society change, the definition of family has to evolve as well. Changing your ideas and definitions of family is an important part of providing inclusive programs.

What many consider as “family” has changed over time partly due to divorce, remarriage, globalization, cohabitation, gender-diverse partners, and more women entering the workforce full-time (Kendall, 2019; Parker & Minkin, 2023). As reported by the Pew Research Center (Parker & Minken, 2023), the change in the American family structure has shifted our thinking about what constitutes a family unit. Today, families are more diverse in their composition and gender roles.

Data Checkpoint

“In 1970, 67% of Americans aged 25-49 were married, living with their spouse and one or more children under the age of 18 years” (Parker & Minken, 2023). By 2021 this number dropped to 37% of married couples living with their children under the age of 18 years (Parker & Minken, 2023).

Discuss the following question:

- How do you define family, and what experiences, values, or relationships have shaped that definition over time?

1.3 Family Structures

Family structures are diverse and ever-evolving, shaped by cultural, societal, and individual differences. Understanding these various family configurations is crucial for educators to create inclusive and supportive environments that recognize and respect the unique needs of every child. This section will explore different family types and their dynamics, beginning with Table 1a (the table is not an all-inclusive list). Recognizing and valuing these diverse family types are key to promoting acceptance, understanding, and equality in educational settings.

| Family Type | Description |

|---|---|

| Single-Parent Family | The population of the U.S. who are not married, but who serve as parents (Kendall, 2019). |

| Dual-Parent Family | A child is raised by two parents who share caregiving responsibilities, regardless of gender, marital status, or biological relationships to the child. |

| Other Relative Care | Children whose parents are unable to care for them (for any reason) may be cared for by extended family members, such as grandparents, aunts, uncles, or cousins, including those who may not be biologically related but play a significant role in the child’s life. |

| Teen Parents | Teenage individuals who have children. Many are in high school when this occurs. They are often able to return to school, and there are programs on some high school campuses where teens may bring their child. They may receive parenting classes in addition to their high school curriculum. |

| Adoptive Family | Family in which one or more adults become the legal parents of a child who is not biologically their own. Families who choose to adopt children must start and complete an extensive home study approval process. There are many personal reasons a family chooses to become an adoptive family and there are many different forms of adoption, like domestic, international, and open adoption to name a few. |

| Foster Family | Children placed in temporary care due to extenuating circumstances involving their family of origin are often placed in homes licensed to care for children. The adults who care for these children must go through strict protocols to provide the support and care that these vulnerable children will need. You may also hear the families fostering these children referenced as “resource families.” The intent of the foster system is to reunite the children with their family of origin whenever possible. When reunification is not possible, guardianship or adoption may be pursued. |

| Blended Family | A blended family represents a unique and diverse family structure that brings together children and parents from different backgrounds into one household. It requires adaptability, communication, and cooperation to navigate the emotional, social, and logistical challenges, but it also provides opportunities for new relationships, support networks, and shared experiences (Gonzalez-Mena, 2016). |

| Communal Family | A family structure where multiple families or individuals live together and share responsibilities, resources, and child-rearing duties. This arrangement emphasizes collective living, cooperation, and shared decision making among its members. In a communal family, the focus is on the well-being of the entire community rather than just individual family units, and resources such as food, finances, and caregiving are often pooled together. |

| Group Home Family | A living arrangement where children or individuals who cannot live with their families (due to various reasons such as abandonment, neglect, behavioral needs, or disability) are cared for in a structured, residential setting. Group homes are typically staffed by adult professionals, and the residents live together as a family unit with shared responsibilities, routines, and support systems. |

| Gender-Diverse Parent Family | Parents who identify with the LGBTQ+ community and their children (Kendall, 2019). There are many ways in which they may decide to form their family such as adoption, reproductive technology, egg or sperm donors, or bring children from previous relationships. |

| Children With an Incarcerated Parent | Sometimes children are cared for by one caregiver while the parent is incarcerated. While the incarcerated parent who is away, the family structure changes, requiring children to adjust to temporary changes in routines and caregiving. |

| Children With Parents in the Military | Children with a parent serving in the military often experience unique family dynamics due to deployments, relocations, and long periods of separation. When a parent is deployed, the family structure shifts, requiring children to adjust to temporary changes in routines and caregiving. |

| Cohabitation and Domestic Partner | Two people who live together and refer to themselves as a couple, without legally being married (Kendall, 2019). Recently, many parents are deciding to raise children together but not to marry. The only difference is that they do not have a legal marriage license; however, their family structure is the same as dual-parent families regardless of gender. |

By exploring and understanding various family structures, educators can create more inclusive and nurturing environments that support the unique needs of every child. Recognizing the diversity of families not only reflects the reality of children’s lives but also promotes empathy, respect, and community within the educational environment.

1.4 Trends

Historically, there has been societal pressure for parents to develop families that are considered traditional or nuclear (Kendall, 2019). From a traditional perspective, the term “nuclear family” is defined as follows:

“A group of people who are related to one another by blood, marriage or adoption and who live together, form an economic unit, and bear and raise children” (Kendall, 2019, p. 193).

However, this traditional definition of family has expanded over time to include diverse and multicultural notions. A modern family incorporates more diverse living arrangements and relationships, including single-parent households, cohabiting unmarried couples, domestic partnerships of LGBTQ+ couples, and several generations of family members (i.e., other relative care) living under the same roof (Kendall, 2019). To include all the diverse living arrangements, Kendall (2019) defines the modern family as the following: “…relationships in which people live together with commitment, form an economic unit and care for any young, and consider the group critical to their identity.”

Similarly, the Administration for Children and Families (2020) explains how family can be “…biological or nonbiological, chosen or circumstantial. They are connected through cultures, languages, traditions, shared experiences, emotional commitment, and mutual support” (p. 1).

Let’s pause to think about the aspects of a family’s unit. Have you ever considered how some of the individuals in your life, who are not related to you by blood or marriage, still hold an irreplaceable spot at family gatherings? These connections, which we often take for granted, are part of what sociologists call “fictive kinship” (Fordham & Ogbu, 1986; Fordham, 1998). Fictive kinship refers to the “intense sense of group loyalty and membership extending beyond conventional family relationships” (Fordham & Ogbu, 1986). This fascinating social arrangement allows us to form family bonds based on factors beyond genetics and legal ties. Explore examples of fictive kinship in Table 1b.

| Example | Description |

|---|---|

| Godparents |

|

| Ritual Kinship

Compadrazgo (coparent) |

|

| Milk Kinship |

|

| Milk Mothers |

|

As illustrated by the definitions above, the concept of family is not fixed. Media, both traditional and digital, play a key role in shaping and evolving public perceptions of what constitutes a family.

Television sitcoms offer a window into how the definition and structure of families have evolved over time. In early examples like Leave It to Beaver (1957–1963), the family is portrayed as a traditional nuclear unit, consisting of a stay-at-home mother, a breadwinning father, and two children. This depiction reinforced mid-20th-century norms about gender roles, parenting, and what a “normal” family should look like. In contrast, contemporary shows such as This Is Us (2016–2022) reflect a broader and more inclusive view of family life. The show follows a multigenerational, racially diverse family formed through birth and adoption, exploring themes such as grief, disability, mental health, and blended families. It emphasizes emotional closeness and resilience over conformity to traditional family structures. Another example, Girlfriends (2000–2008), centers on a group of close friends who form a chosen family, supporting one another through life’s challenges. Their relationships reflect fictive kinship—emotional and practical bonds that function like family ties without legal or biological connections. Together, these shows illustrate how families in media have become more complex and diverse, paralleling real-world shifts in how families are formed and defined. For early childhood educators, this evolution highlights the importance of recognizing and respecting a wide range of family structures, emphasizing that what unites all families is not their form but their commitment, care, and emotional connection.

As you engage with various forms of media, be mindful of the images that are portrayed. What kind of people and families do you see represented? While the representation of women, people of color, and people of differing sexualities and gender expressions has increased in media, they still predominantly play less consequential characters within the plot lines. As early childhood educators recognize and honor the differences in family structures, they must be mindful of how the common thread noted within all family units is commitment, caring, and the close emotional ties (Benokraitis, 2015). Individuals can achieve such family goals without mirroring a traditional family unit.

Reflect

Discuss the following questions:

- Are there family structures, included in this section, with which you were not previously familiar? Explain.

- Imagine that you are working with families in a school or community setting. What level of comfort do you have in working with diverse families? What may be challenging for you? What are some strategies that you could use to help you in working on the biases that you may have?

- Reflect on the traditional and modern definitions of “family.” To which type of family do you belong? To which type of family do most of your friends/acquaintances belong? Which type of family definition describes the families whom you work with in your programs? Compare and contrast.

- What is missing from these traditional and modern definitions of “family” that are presented in this section? What would you add to the definition of “family”?

- How can you ensure that a family’s “kin” are also included in the everyday life of your early education program? What program policies can be maintained, changed, or developed to provide inclusive family spaces?

- How has your perception of families in media changed over time? What shows or films do you feel provide a realistic depiction of diverse families?

1.5 Trends Affecting Families

Families are dynamic units that evolve in response to broader social, economic, and cultural shifts. Educators need to understand the trends that influence families to better support children’s development and foster inclusive environments. This section explores various trends, such as changes in family structures, economic factors, and the influence of technology, and considers how these shifts impact family dynamics and early childhood education. Because family life is ever-changing, it is essential for educators to stay current on emerging trends and societal changes. Doing so allows them to respond thoughtfully to the diverse realities of children’s home lives, avoid assumptions based on outdated models, and build respectful, supportive relationships with all families.

Changing Family Structures

Over recent decades, family structures have become more diverse. Traditional nuclear families are less common, while single-parent, gender-diverse parents, and blended families are increasingly visible (Feeney et al., 2019). In early childhood education, it is crucial for teachers to recognize and accommodate this diversity by adopting inclusive teaching practices. Educators must avoid making assumptions about family roles and responsibilities, ensuring that all children feel respected and supported in their family dynamics (Gonzalez-Mena, 2016). Every family is unique, and as early childhood educators, it is essential that we respect and celebrate these differences to create an inclusive and supportive learning environment for all children, even if those family structures do not match our own. Being a reflective educator will assist us in this area.

Economic Pressures

Economic shifts, such as the rise of dual-income households and an increase in income inequality or the high cost of childcare, have placed additional strain on families. Many families now rely on both parents working, which can affect childcare arrangements and family time (Owen & Ware, 2020). These economic pressures can lead to stress that impacts parenting styles and the availability of resources for children, which, in turn, can affect children’s emotional and academic development (Bronfenbrenner, 2005).

Technological Advancements

Technology has profoundly reshaped how families communicate and interact. The rise of smartphones, social media, and digital entertainment has affected family dynamics, with some families experiencing a “technology gap” between generations (Livingstone, 2018). Children are exposed to digital devices at increasingly younger ages, which can influence their social skills, attention spans, and learning styles. As a result, early childhood educators must find a balance between using technology as a learning tool and encouraging traditional, play-based learning to support children’s development together with the family (Palaiologou, 2016).

Cultural Diversity and Globalization

Immigration and increased globalization have led to more culturally diverse family groups, expanding the range of languages, values, and traditions present in early childhood classrooms. Many children grow up in households that blend multiple cultural traditions, religious practices, and family customs, creating a rich and complex mix of lived experiences (Gonzalez-Mena, 2016). These families may include recent immigrants, refugees, multilingual households, or families with strong transnational ties, where cultural identity is maintained through connection to extended family, community networks, and cultural practices across borders. Additionally, LGBTQ+ families, multiracial families, and families formed through adoption or foster care bring unique structures and perspectives that challenge traditional definitions of family.

Indigenous peoples provide a strong example of how culture shapes family structures and values. Many Indigenous families emphasize intergenerational caregiving, where grandparents, aunts, uncles, and tribal communities share responsibilities in raising children. Traditional knowledge, oral storytelling, and spiritual practices are often passed down through generations, fostering cultural identity, belonging, and resilience. These family dynamics reflect collective responsibility and a deep respect for ancestral wisdom.

It is important for early childhood educators to incorporate both multicultural and Indigenous perspectives into their curriculum and practice. This includes recognizing Indigenous ways of knowing, honoring tribal sovereignty, and integrating culturally responsive teaching practices that reflect the languages, histories, and traditions of all the families they serve. Educators must also be mindful of how their own cultural lens influences their expectations and interactions. By valuing and respecting the diverse backgrounds that families bring to the classroom, educators can create a more inclusive and affirming learning environment—one that nurtures every child’s identity, fosters belonging, and builds strong school–family partnerships (Feeney et al., 2019).

Work–Life Balance

As societal norms shift, there has been a growing expectation for more shared parenting responsibilities between mothers and fathers. The concept of “work–life balance” has gained prominence as families try to navigate professional demands and caregiving roles (Bianchi & Milkie, 2010). The rise of remote and hybrid work arrangements has further reshaped family dynamics, allowing some parents greater flexibility to be more involved in daily caregiving tasks. However, blurred boundaries between work and home life can also present challenges, as parents may struggle to set limits on work obligations while meeting the needs of their children.

Work–life balance challenges can create stress, but they also offer opportunities for fathers to take more active roles in caregiving, challenging traditional gender roles in parenting and fostering a more equitable division of family responsibilities (Feeney et al., 2019). Additionally, nontraditional family structures, including gender-diverse parents, single parents, and multigenerational households, have become more visible, further expanding conversations about equitable caregiving and the diverse ways families navigate work and home life.

As workplace policies continue to evolve, including paid parental leave, flexible scheduling, and family-friendly benefits, there is potential to further support parents in managing their dual roles. For early childhood educators, understanding these changing family dynamics is essential in fostering empathy, collaboration, and support for children and families who are adapting to new models of work and caregiving.

Health and Well-Being

Rising concerns about physical and mental health have significantly influenced family life. Increased awareness of mental health issues, particularly among parents and children, has led to shifts in how families approach well-being and seek support (Owen & Ware, 2020). Mental health challenges, including stress, anxiety, and depression, are increasingly being recognized in early childhood. As a result, educators must be prepared to support children from families coping with health-related issues, ensuring that children’s emotional needs are met and their development is nurtured (Bronfenbrenner, 2005).

However, while awareness of mental and physical health needs has grown, many families continue to struggle with access to adequate health care and insurance. Families with lower incomes, immigrant families, and those living in rural areas often face significant barriers to receiving timely medical, dental, and mental health care. Limited provider availability, long wait times, high out-of-pocket costs, and restrictive insurance networks prevent many children from receiving early intervention, counseling, or necessary medical treatments. Additionally, the stigma surrounding mental health in some communities may discourage families from seeking help, further delaying crucial support.

Families who rely on employer-provided health care may struggle if they have inconsistent work schedules, part-time jobs, or gig-based employment that does not offer benefits. Meanwhile, families who do qualify for Medicaid or the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP) may still encounter difficulties finding providers who accept public insurance, particularly for mental health services. Gaps in coverage can leave families with limited options, forcing them to make difficult decisions about prioritizing health care over other essential expenses.

The effects of these challenges extend into the classroom, where children experiencing untreated physical or mental health issues may have difficulty focusing, regulating emotions, or fully engaging in learning. Early childhood educators play a crucial role in recognizing signs of distress, providing a supportive environment, and connecting families to available community resources. Schools and early childhood programs can help bridge gaps by integrating social-emotional learning, trauma-informed practices, and partnerships with health care providers to ensure children receive the care they need.

1.6 Family Circumstances

Family members’ actions, behaviors, and decision-making processes are often shaped by a variety of circumstances, including socioeconomic status, cultural expectations, mental and physical health, and family dynamics. Understanding how these factors influence family life is essential for educators to support children’s development and family well-being. This section will explore how these circumstances affect both children and adults in families, shaping relationships, behavior, and educational outcomes.

Socioeconomic Status

Socioeconomic status (SES) is one of the most significant factors influencing family life. Families with lower incomes often face increased stress due to financial instability, limited access to resources, and a lack of time for meaningful family interactions because of work demands (Conger & Donnellan, 2007). These stresses can affect parenting styles, sometimes leading to authoritarian approaches or reduced supervision, depending on the family’s circumstances. Children from low-SES families may experience challenges such as limited access to educational resources, extracurricular activities (dance, soccer, etc.), and adequate health care, which can hinder their academic performance and social-emotional development (Bradley & Corwyn, 2002).

Parental Mental Health

Parental mental health plays a critical role in shaping family dynamics. Parents experiencing mental health challenges, such as depression or anxiety, may struggle with emotional regulation, which can impact their parenting behaviors, family interactions, and decision making (Lovejoy et al., 2000). Children of parents with mental health conditions may experience emotional distress, behavioral challenges, or take on greater responsibilities within the household, leading to developmental challenges. Support systems and resources are crucial in mitigating these effects and promoting healthier family functioning (National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2010).

Family Conflict and Divorce

High levels of family conflict or divorce can lead to significant changes in family dynamics and parenting approaches. Research indicates that parental conflict, whether resolved or ongoing, affects the emotional stability of both parents and children (Amato, 2010). Divorce, while sometimes necessary, often leads to changes in living arrangements, economic status, and parenting time, all of which influence how family members interact and make decisions. Children in families with high conflict or divorce may experience emotional turmoil and academic and behavioral needs, especially if the conflict is prolonged or if they feel caught between parents. However, children in divorced families can adapt well over time, particularly when parental conflict is minimized and a stable, nurturing environment is provided (Hetherington & Kelly, 2002).

Cultural Expectations

Culture refers to the shared values, beliefs, customs, practices, behaviors, and artifacts that characterize a group of people or society. It includes elements such as language, religion, food, clothing, art, traditions, and social norms, which are passed down from generation to generation. Culture shapes how individuals think, interact, and interpret their world, creating a sense of identity and belonging within a group. Cultural norms and expectations shape how families organize themselves, make decisions, and interact with each other. In many cultures, extended family plays a significant role in caregiving and decision making, and expectations regarding children’s roles, respect for elders, and gender roles can vary widely (Gonzalez-Mena, 2016). Families with strong cultural ties may prioritize collective well-being over individual desires, influencing how they handle education, discipline, and family responsibilities. Children raised in a culture different from their peers may experience different expectations, which can affect their social interactions and identity development. Educators must be culturally competent to support children from diverse backgrounds and respect family values, ensuring that all children feel valued and understood (Rogoff, 2003).

Physical Health of Family Members

The physical health of family members can significantly impact family life. Chronic illness or disability may require additional caregiving responsibilities, affect family routines, and influence economic decisions, especially if one or both parents must reduce work hours or leave the workforce to care for a family member (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine, 2016). Children in families with chronic illness or disability may experience increased anxiety, caregiving responsibilities, or feelings of isolation. Support from health care professionals and programs is crucial in helping these children cope with the demands placed on them by their family’s health circumstances, ensuring their emotional and developmental needs are met (Seligman & Darling, 2007).

Substance Abuse

Substance abuse within a family can disrupt normal family functioning, leading to instability, neglect, or conflict. Parents struggling with addiction may have difficulty maintaining consistent routines or providing emotional support, while other family members may either enable the behavior or attempt to compensate for the dysfunction (Rahimi & Shooli, 2024). Children in households with substance abuse are at greater risk for neglect, emotional trauma, and developmental concerns. They may adopt coping mechanisms that include acting out or withdrawing, and they often require external support from schools, counselors, or social services to help address the emotional and developmental challenges they face (Kelley et al., 2010).

The circumstances within families greatly influence the actions of both children and family members, shaping their emotional, social, and developmental outcomes. By recognizing the complex factors that families face, educators can offer more compassionate, individualized support that promotes resilience and well-being for all family members.

Ecological Systems Theory

Urie Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory provides a framework for understanding the multiple layers of influence on a child’s development (Bronfenbrenner, 1979, 1986). Bronfenbrenner studied Freud, Erikson, Piaget, and other learning theorists and believed that all their theories could be enhanced by adding the dimension of context (Bronfenbrenner, 1979). What is being taught and how society interprets situations depend on who is involved in the life of a child and where a child lives or their community. Bronfenbrenner’s ecological system model explains the direct and indirect influence that systems have on an individual’s development.

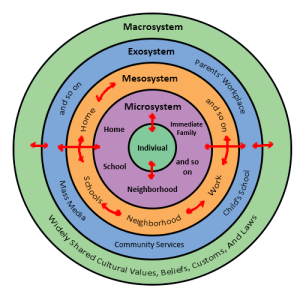

Figure 1a and the corresponding text provides an overview of Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory, demonstrating how each layer of society has a direct impact on a child’s development:

- Microsystem: Serves as the immediate environment that impacts a child directly. The relationship between individuals and those around them must be considered. These are the people such as parents, peers, educators, and community members with whom the child interacts.

- Example: Supportive parents who read to their child and provide educational activities may positively influence cognitive and language skills.

- Mesosystem: Interactions between those surrounding the child, like the relationship between a child’s home and early childhood program, will impact their development.

- Example: A child whose parents are actively involved in their education, such as attending parent–educator conferences and volunteering for school events, may perform better academically.

- Ecosystem: Larger institutions such as the mass media or the health care system are ecosystems. These have an impact on families and peers and early education settings/schools who operate under policies and regulations found in these institutions.

- Example: If a parent’s workplace offers flexible working hours or work-from-home options, the parent might have more time to spend with their children, positively impacting the child’s emotional development and family relationships.

- Macrosystem: Broader cultural and societal influences are at the level of macrosystems. These larger ideals and expectations inform institutions that will ultimately impact the individual.

- Example: In a society that highly values individual achievement, children might be encouraged to be more competitive and independent.

- Chronosystem: All this happens in an historical context referred to as the chronosystem. Cultural values change over time, as do policies of educational institutions or governments in certain political climates. Development occurs at a point in time (Bronfenbrenner & Morris, 2006).

- Example: The introduction of widespread Internet access and social media represents a significant chronosystem change for many children.

Reflect

Discuss Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory by answering the following questions:

- Think of an example of each system. How it has impacted your life thus far?

- How have your unique family circumstances—such as structure, culture, values, or life events—shaped your development within each of Bronfenbrenner’s systems?

1.7 Classroom Resources and Strategies for Teaching Family Diversity

Understanding and teaching about diverse family patterns is crucial in early childhood education. The evolving nature of family structures requires educators to be well-versed in current literature and equipped with educational resources that reflect the variety of family experiences. By engaging with diverse family representations, educators can create inclusive environments that honor every child’s background and provide culturally responsive pedagogy. This section will explore key literature, classroom resources, and teaching strategies related to diverse family patterns and trends.

Inclusive Curriculum Design

When planning lessons, educators should intentionally incorporate materials that reflect various family structures, creating an inclusive curriculum. This can be achieved through the selection of storybooks, family-themed projects, and discussions that allow children to share their own family experiences. Educators can also integrate topics like adoption, foster care, and blended families into social studies or family-themed lessons (Feeney et al., 2019). Additionally, a classroom wall or bulletin board can be dedicated to showcasing the diverse family structures of students. Each child can contribute pictures or drawings of their family, which helps foster a sense of belonging and validates the different family configurations represented in the classroom (Couchenour & Chrisman, 2018).

Children’s Literature Examples

- The Family Book by Todd Parr: This vibrant picture book celebrates all kinds of families, including those with two moms or two dads, single parents, and large extended families. Its simple language and colorful illustrations make it an excellent resource for introducing young children to the concept of family diversity.

- Stella Brings the Family by Miriam B. Schiffer: This story features a young girl with two dads, tackling the question of how to celebrate Mother’s Day in a way that reflects her unique family structure. It is a valuable tool for teaching children about the different ways families are formed and how love defines a family.

- All Are Welcome by Alexandra Penfold: A beautifully illustrated book that emphasizes inclusion and diversity in schools, All Are Welcome depicts children from a variety of family backgrounds, cultures, and traditions. It is a great resource for building an inclusive classroom environment.

Collaborative Learning with Families

Encouraging families to share their unique stories and traditions with the class is an effective way to foster an inclusive environment. Inviting parents and caregivers to participate in classroom activities allows children to see different family roles and cultural practices firsthand, promoting empathy and understanding among peers (Gonzalez-Mena, 2016). Another valuable approach is assigning children a family book project, where they can share their family’s history, traditions, and interests. This project can be made into a classroom book, stored in the library center, or read during large-group time. This project can further enhance children’s understanding and appreciation of diversity (Gonzalez-Mena, 2016).

Use of Multimedia and Technology

Educators can use digital tools to create interactive storytelling sessions, allowing children to explore stories about diverse families from around the world. Websites like PBS Kids and Storyline Online offer age-appropriate, family-centered stories that reflect various family patterns. Additionally, short videos or documentaries showcasing different family forms can be valuable resources.

Exploring literature and classroom resources related to diverse family patterns is essential for creating inclusive and culturally responsive learning environments. Early childhood educators can draw from a wealth of books, research, and teaching strategies to ensure that all children see their families represented and valued in the educational environment. By actively engaging with these resources, educators support the development of empathy, respect, and understanding among their students.

Multicultural Resources

1.8 Conclusion

In conclusion, the study of family patterns and trends in early childhood education highlights the importance of recognizing and embracing the diverse configurations and circumstances that shape family life. As society evolves, so does the concept of family, requiring educators to adopt inclusive and culturally responsive practices. By understanding the various family structures—from traditional nuclear families to gender-diverse parent households, blended families, and other relative-led homes—educators can create learning environments that reflect the lived realities of their students.

Moreover, the changing trends affecting families, such as economic pressures, technological advancements, and shifts in work–life balance, underscore the need for educators to be flexible and supportive. Family circumstances, such as socioeconomic status, mental health, and cultural expectations, influence children’s development and behavior. Early childhood educators must be equipped to navigate these complexities, offering compassion and individualized support.

Ultimately, a focus on family diversity enriches the educational experience by fostering empathy, respect, and community. By exploring literature and utilizing classroom resources that represent various family dynamics, educators can ensure that every child feels seen and valued, creating a foundation for lifelong learning and inclusivity.

Case Study

The Johnson family consists of Tamara, a single mother, and her two children—Malik, age 6, and Ava, age 2. Tamara recently relocated to a new city to pursue better job opportunities and is now working full-time as a nurse. This move meant leaving behind her extended family, who had previously played a significant role in caregiving. As Tamara works long and irregular shifts, she has come to rely on a small group of neighbors for help with childcare. These neighbors include a retired couple who help occasionally, and a college student who babysits as needed. While supportive, these arrangements are not always consistent, which has created some gaps in caregiving routines. The neighbors do not have ongoing relationships with the children beyond occasional care, and the people involved change depending on availability, which means the children do not have consistent caregivers outside of their mother.

Tamara’s family structure—a single-parent household with limited extended family support—affects both children in unique ways. Malik, now in first grade, has started showing signs of emotional distress, including frequent outbursts, difficulty focusing, and anxious behaviors at school. Some educators have wondered if his behaviors are directly tied to the stress of transition, inconsistency in routines, or emotional needs related to recent changes. Ava, while still a toddler, has become increasingly clingy and experiences separation anxiety when Tamara leaves for work, possibly due to having multiple caregivers and unpredictable routines.

While both children demonstrate strengths—Malik is bright and curious, and Ava is playful and observant—they also face emotional and developmental challenges linked to instability in their caregiving environment. It is important to avoid assumptions based on family structure alone and instead consider a broader view of the family’s unique circumstances, strengths, and needs.

Reflect and discuss the following questions:

- How can family structure and caregiving responsibilities impact a child’s emotional and academic development?

- What resources or support systems could help families like the Johnsons improve stability and well-being for both parents and children?

- Why is it essential for communities and educators to recognize the diversity in family structures and offer tailored support?

- How do the changing caregiving arrangements in this case affect the consistency and stability that young children typically need?

- How could Bronfenbrenner’s ecological systems theory help us understand the various layers influencing Malik and Ava’s development (e.g., the role of neighbors, school, work schedules, and community resources)?

1.9 Learning Activities

1.10 References

Administration for Children and Families. (2020). Partnering with families of children who are dual language learners. Building Partnerships Series. For Head Start and Early Head Start Professionals. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED609049.pdf

Amato, P. (2010). Research on divorce: Continuing trends and new developments. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72, 650–666. http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00723.x

Benokraitis, N. V. (2015). Marriages & families: Changes, choices, and constraints, 8e. Pearson.

Bianchi, S. M., & Milkie, M. A. (2010). Work and family research in the first decade of the 21st century. Journal of Marriage and Family, 72(3), 705–725. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1741-3737.2010.00726.x

Bradley, R. H., & Corwyn, R. F. (2002). Socioeconomic status and child development. Annual Review of Psychology, 53, 371–399. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135233

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1979). Contexts of child rearing: Problems and prospects. American Psychologist, 34(10), 844–850. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.34.10.844

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723–742. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723

Bronfenbrenner, U. (Ed.). (2005). Making human beings human: Bioecological perspectives on human development. Sage Publications.

Bronfenbrenner, U., & Morris, P. A. (2006). The bioecological model of human development. In R. M. Lerner & W. Damon (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology: Theoretical models of human development, 793–828. John Wiley & Sons.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). About nutrition. https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/php/about/?CDC_AAref_Val=https://www.cdc.gov/nutrition/about-nutrition/index.html

Conger, R. D., & Donnellan, M. B. (2007). An interactionist perspective on the socioeconomic context of human development. Annual Review of Psychology, 58(2007), 175–199. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.58.110405.085551

Couchenour, D., & Chrisman, K. (2018). Families, schools, and communities: Building partnerships for educating children. Cengage Learning.

Feeney, S., Moravcik, E., & Nolte, S. (2019). Who am I in the lives of children? An introduction to early childhood education. Pearson Education.

Fordham, S. (1998). Blacked out: Dilemmas of race, identity, and success at Capital High. University of Chicago Press.

Fordham, S., & Ogbu, J. U. (1986). Black students’ school success: Coping with the “burden of acting white.” The Urban Review, 18(3), 176–206. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED281948.pdf

Gonzalez-Mena, J. (2016). Diversity in early care and education: Honoring differences. McGraw-Hill Education.

Hetherington, E. M., & Kelly, J. (2002). For better or for worse: Divorce reconsidered. Norton.

Kelley, M. L., Klostermann, K., Doane, A. N., Mignone, T., Lam, W. K. K., Fals-Stewart, W., & Padilla, M. A. (2010). The case for examining and treating the combined effects of parental drug use and interparental violence on children in their homes. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 15(1), 76–82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2009.09.002

Kendall, D. (2019). Social problems in a diverse society. Pearson.

Kumar, P. (2022). Fictive kinship: Social bonds beyond blood and marriage. Sociology Institute. https://sociology.institute/sociology-of-kinship/fictive-kinship-social-bonds-beyond-blood-marriage/#What_is_fictive_kinship

Livingstone, S. (2018). The class: Living and learning in the digital age. NYU Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctt18040ft

Lovejoy, C., Graczyk, P. A., O’Hare, E., & Neuman, G. (2000). Maternal depression and parenting behavior: A meta-analytic review. Clinical Psychology Review, 20(5) 561–592. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7358(98)00100-7

Owen, M. T., & Ware, A. M. (2020). Families and children: Diverse perspectives and impact on early childhood education. In S. L. Kagan & E. T. T. Reynolds (Eds.), Early childhood education: Dilemmas and directions (pp. 45–64). Routledge.

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. (2016). Families caring for an aging America. National Academies Press. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK396398/

National Scientific Council on the Developing Child. (2010). Persistent fear and anxiety can affect young children’s learning and development: Working paper no. 9. https://developingchild.harvard.edu/resources/working-paper/persistent-fear-and-anxiety-can-affect-young-childrens-learning-and-development/

Palaiologou, I. (2016). Children under five and digital technologies: Implications for early years pedagogy. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 24(1), 5–24. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/1350293X.2014.929876

Parker, K., & Minken, R. (2023). Public has mixed views on the modern American family. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2023/09/14/public-has-mixed-views-on-the-modern-american-family/

Rahimi, L., & Shooli, Z. A. (2024). How parental substance abuse affects family functioning and child psychological health. Iranian Journal of Neurodevelopmental Disorders, 3(2), 1–10. https://maherpub.com/jndd/article/view/291

Rogoff, B. (2003). The cultural nature of human development. Oxford University Press.

Seligman, M., & Darling, R. B. (2007). Ordinary families, special children: A systems approach to childhood disability. Families, Systems, & Health, 25(4), 453–454. https://doi.org/10.1037/1091-7527.25.4.453

Van Eeden-Moorefield, B., & Demo, D. H. (2007). Family diversity. In G. Ritzer (Ed.), Blackwell encyclopedia of sociology. Blackwell Publishing. Blackwell Reference Online.

Images:

1a: “Urie_Bronfenbrenners_Bioecological_Model” by Lopezmarielys is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0