Chapter 14: Trauma Part 01

Jamie Howell

14.1 Introduction

(needs to be written to be consistent with other chapters)

Learning Objectives

- Overview of Trauma

- Trauma and the Abdomen

- Chest Trauma

- Bleeding

- Environmental Emergencies

- Head, Facial, Neck and Spine Trauma

Overview of Trauma

Trauma is a leading cause of death and disability in the United States, particularly among individuals under the age of 45. In 2023, unintentional injuries were the third leading cause of death, following heart disease and cancer.

The CDC’s National Center for Health Statistics reports that in 2022, there were 227,039 deaths due to unintentional injuries, equating to a death rate of 68.1 per 100,000 population . The primary causes of these fatalities included:

- · Unintentional poisonings: 102,958 deaths (30.9 per 100,000 population)

- · Unintentional falls: 44,630 deaths (14.0 per 100,000 population)

- · Motor vehicle traffic incidents: 44,534 deaths (13.4 per 100,000 population)

Overall, injury-related deaths, encompassing both unintentional and intentional causes, totaled 307,785 in 2022, with a death rate of 92.3 per 100,000 population.

Recognized in the “White Paper” that launched modern EMS, the report sent to President Lydon Johnson in 1966 titled “Accidental Death and Disability: The Neglected Disease of Modern Society” brought to light the impact of accidental injuries as the leading cause of death in the first half of American’s life span. It was stated that in 1965, vehicle crashes killed more Americans than soldiers who died in the Korean War during the same time. The call came for civilian training and ambulance operations standards. This led to the first nationally recognized curriculum for the emergency medical technician-ambulance (EMT-A) in 1969.

For EMRs, trauma is a familiar and urgent reality. Whether arriving at the scene of a vehicle collision, a fall, a gunshot wound, or an industrial accident, you are often the first to assess, stabilize, and initiate care for the injured.

The trauma sections focus on the mechanisms of trauma, in EMS referred to as a mechanism of injury (MOI), or the physical forces that cause injury to the human body. From blunt force and penetrating injuries to thermal, electrical, and blast trauma, understanding the underlying physics and biology of these mechanisms is essential for effective on-scene decision-making. Quick and accurate assessment of how an injury occurred often determines the course of treatment and can impact the patient’s outcome.

The central focus to this education is utilization of the National Guidelines for the Field Triage of Injured Patients, a project started in 2011 and updated in 2021, that has the input and support of multiple professional organizations.

You can access and download the guidelines by visiting National Guidelines for the Field Triage of Injured Patients PDF.

The Golden Hour and The Platinum Ten Minutes

When it comes to trauma, time is a critical factor. The longer a severely injured patient goes without definitive care—like surgery or intensive hospital treatment—the lower their chance of survival. This concept is known as The Golden Hour. While it’s not a rigid countdown clock, it serves as a reminder that the most critically injured patients need to be in the hands of trauma surgeons within about an hour of the injury to prevent early deaths, especially from blood loss.

Even more urgent is the Platinum Ten Minutes—a goal that EMRs should strive for when caring for seriously injured patients. The aim is to assess and provide treatment for life- or limb-threatening injuries within 10 minutes of arriving on scene.

Mechanism of Injury (MOI)

The mechanism of injury (MOI) refers to how an injury happened and the energy forces involved. Understanding MOI gives you valuable clues about what injuries to expect—even if you can’t see them yet.

Some significant mechanisms of injury include:

-

- Penetrating injuries to the head, neck, torso, and proximal extremities

- Suspected spinal injury with new motor or sensory loss

- Active bleeding requiring a tourniquet or wound packing with continuous pressure

An example of high risk physical findings:

- Unable to follow commands (motor GCS <6)

Moderate risk mechanism of injury to note:

-

- High-risk auto crash:

- Significant intrusion into the vehicle (more than 12 inches at occupant site)

- Complete or partial ejection

- Death of another passenger in the same compartment

- Vehicle telemetry suggesting serious impact

- High-risk auto crash:

- Pedestrian/bicycle rider thrown, run over, or with significant impact

Other less significant MOIs—like minor falls or isolated injuries—may not require trauma center care, but each case should be considered individually. Factors like the patient’s anatomy, age, or chronic conditions may elevate their risk.

Don’t forget special considerations:

- Spinal motion restriction (SMR) should be applied promptly if the MOI or symptoms suggest a spine injury.

- Assess the entire body, including the back, to catch injuries you might not see at first.

Primary Survey (Review)

The primary survey is your rapid, systematic scan for life-threatening conditions. It uses the XABCDE approach, which you should memorize and practice until it becomes second nature.

- X – Exsanguination: Immediately control massive, visible bleeding.

- A – Airway: Ensure it’s open and protected; use airway adjuncts if necessary.

- B – Breathing: Look, listen, and feel; provide oxygen or ventilate if needed.

- C – Circulation: Check pulse, skin condition, and look for hidden bleeding.

- D – Disability: Assess responsiveness using AVPU and consider the Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS).

- E – Exposure/Exam: Undress the patient to check for hidden injuries and perform a quick head-to-toe scan. Always consider the need for spinal motion restriction (SMR).

Secondary Survey (Review)

Once immediate threats are addressed, you’ll perform the secondary survey, which is a more detailed examination and history-taking process. Here’s what it includes:

- Full body scan: Look for pain, deformities, bleeding, crepitus, swelling, and open wounds.

- Focused exam: Targeted assessment based on chief complaint or MOI.

- Vital signs: Record and monitor trends.

Your goal is to uncover any injuries missed in the primary survey and ensure the patient remains stable.

Management of the Trauma Patient

Managing a trauma patient means doing what’s necessary in the moment—but also making smart choices about where the patient needs to go. Key considerations include:

- Rapid transport: Critical patients should be packaged and moved quickly. If the transport time is long, air transport may be faster and more appropriate.

- Destination selection: Transport patients to facilities that match the level of care they need. For example:

- Trauma Red/Level 1: For patients with life-threatening trauma

- Trauma Yellow/Level 2: For patients with serious, but not immediately life-threatening, trauma

- Trauma system: Understand how local hospitals are categorized and what services they offer. Follow your region’s trauma activation protocols.

Pediatric Considerations in Trauma

Children respond to trauma differently than adults. They are more resilient in some ways—but also more fragile in others. Trauma is the leading cause of death in children, and blunt force injuries are the most common type.

Injury patterns in children can include:

- Motor vehicle crashes:

- Unrestrained: Head and neck injuries

- Restrained: Abdominal and lower spine injuries

- Bicycle and pedestrian accidents: Often result in head and abdominal injuries

- Burns and sports injuries: Typically involve the head, face, or spine

Use a calm and reassuring tone with pediatric patients, involve caregivers when possible, and be sensitive to the child’s emotional state.

Geriatric Considerations in Trauma

Older adults face unique risks when it comes to trauma. Falls, car crashes, and burns are major causes of injury, but aging also brings additional challenges like fragile bones, impaired balance, multiple medications, and chronic conditions. Older patients are more likely to be anticoagulated (on blood thinners), which is associated with worse trauma outcomes even for apparently minor injuries.

Also be alert for elder abuse, which may cause unexplained bruises or fractures. Prevention starts with education—help families identify fall risks at home, review medications, and encourage balance or strength exercises.

Define the Kinematics of Trauma

Kinematics is the study of how motion, force, and energy transfer lead to injury. Think of it as the “physics of trauma.” By understanding how a crash or fall happened, you can predict which parts of the body might be injured—even if the injuries aren’t immediately obvious.

For example:

- A rollover car crash may cause head, spine, and chest injuries.

- A fall from a ladder may lead to internal bleeding, spinal fractures, or head trauma.

- A gunshot wound involves high energy transfer and may cause damage far beyond the visible wound.

By combining kinematic insight with your assessment findings, you become a better-informed, more effective responder.

14.2 Trauma and the Abdomen

The abdomen is a complex and vital area of the human body. Situated between the chest and pelvis, it houses essential organs that facilitate digestion, blood filtration, and immune responses. Its vulnerability to injury stems from the absence of a protective bony structure, although the spine and ribs provide partial coverage. Understanding abdominal trauma, its assessment, and management is critical for healthcare providers tasked with saving lives in emergency settings.

Anatomy and Vulnerabilities of the Abdomen

The abdominal region is divided into four quadrants:

- Right Upper Quadrant (RUQ): Contains the liver, gallbladder, and portions of the intestines.

- Left Upper Quadrant (LUQ): Houses the spleen, stomach, and pancreas.

- Right Lower Quadrant (RLQ): Includes the appendix and parts of the intestines.

- Left Lower Quadrant (LLQ): Contains additional portions of the intestines.

Each organ within these quadrants is susceptible to specific types of injury. For example:

- The liver, rich in blood supply, is prone to hemorrhage from blunt force trauma or penetrating injuries.

- The spleen, a blood storage organ, is at risk of rupture from impact, causing rapid blood loss.

- The stomach, a crucial digestive organ, can release food contents into the abdominal cavity when perforated, leading to severe infections.

Case Study: A Roadside Emergency

During a multi-vehicle accident, a 35-year-old man was found unconscious with severe bruising on his upper right abdomen. Upon arrival at the emergency department, diagnostic imaging revealed a lacerated liver. Quick stabilization, including fluid resuscitation and surgical intervention, was crucial in preventing fatal hemorrhagic shock.

Recognizing Abdominal Trauma

Signs and Symptoms:

- Severe abdominal pain, often exacerbated by movement or palpation.

- External bruising or bleeding.

- Nausea or vomiting, potentially with blood.

- Distended or rigid abdomen.

- Cool, clammy skin and signs of shock (e.g., rapid heartbeat, low blood pressure).

- Visible organ protrusion in cases of evisceration.

Assessment Techniques:

- Observation: Look for bruising, swelling, or open wounds.

- Palpation: Gently examine each quadrant, starting away from the site of pain.

- Inspection for Evisceration: Note any protruding organs and take immediate steps to protect them.

- Vital Signs Monitoring: Identify indications of shock or internal bleeding.

- Neurological Assessment: Check sensory and motor function in the extremities.

Types of Abdominal Injuries and Management

Closed Abdominal Injuries: These occur when blunt force damages internal organs without an open wound.

- Care Steps:

- Position the patient on their back.

- Bend the knees slightly to relax abdominal muscles.

- Avoid applying direct pressure to the abdomen.

- Administer supplemental oxygen if indicated.

- Monitor for signs of shock and summon advanced medical care.

Open Abdominal Injuries: Penetrating trauma, such as knife or gunshot wounds, may result in exposed internal organs.

- Care for Evisceration:

- Cover the wound with a moist, sterile dressing.

- Overlay plastic wrap to retain moisture and warmth.

- Avoid re-inserting protruding organs.

- Keep the patient warm and still while awaiting advanced care.

Impaled Objects:

- Care Steps:

- Stabilize the object using bulky dressings to prevent movement.

- Avoid removing the object as it may control internal bleeding.

Critical Thinking Exercise

Reflect on this scenario: You arrive at the scene of a warehouse accident where a worker has been impaled by a metal rod in the lower abdomen. Create a step-by-step plan for immediate care and stabilization until emergency personnel arrive.

Complications of Abdominal Trauma

Injuries to the abdomen can have severe, life-threatening complications:

- Hemorrhagic Shock: Rapid blood loss due to liver or spleen injury.

- Peritonitis: Infection resulting from the leakage of stomach or intestinal contents.

- Respiratory Compromise: Pressure from abdominal swelling can impede breathing.

Real-World Application: The Importance of Quick Action

A 22-year-old college athlete experienced a ruptured spleen after a collision during practice. Prompt recognition of symptoms by a nearby athletic trainer led to immediate transport to the hospital. Emergency surgery prevented fatal complications. This highlights the importance of early identification and intervention in abdominal trauma.

14.3 Chest Trauma

Chest injuries are a significant cause of trauma-related deaths in the United States. Motor vehicle collisions, falls, and direct blows are common mechanisms leading to such injuries. Understanding how to assess and manage chest trauma is crucial for EMRs, who often play a pivotal role in the initial care of these patients.

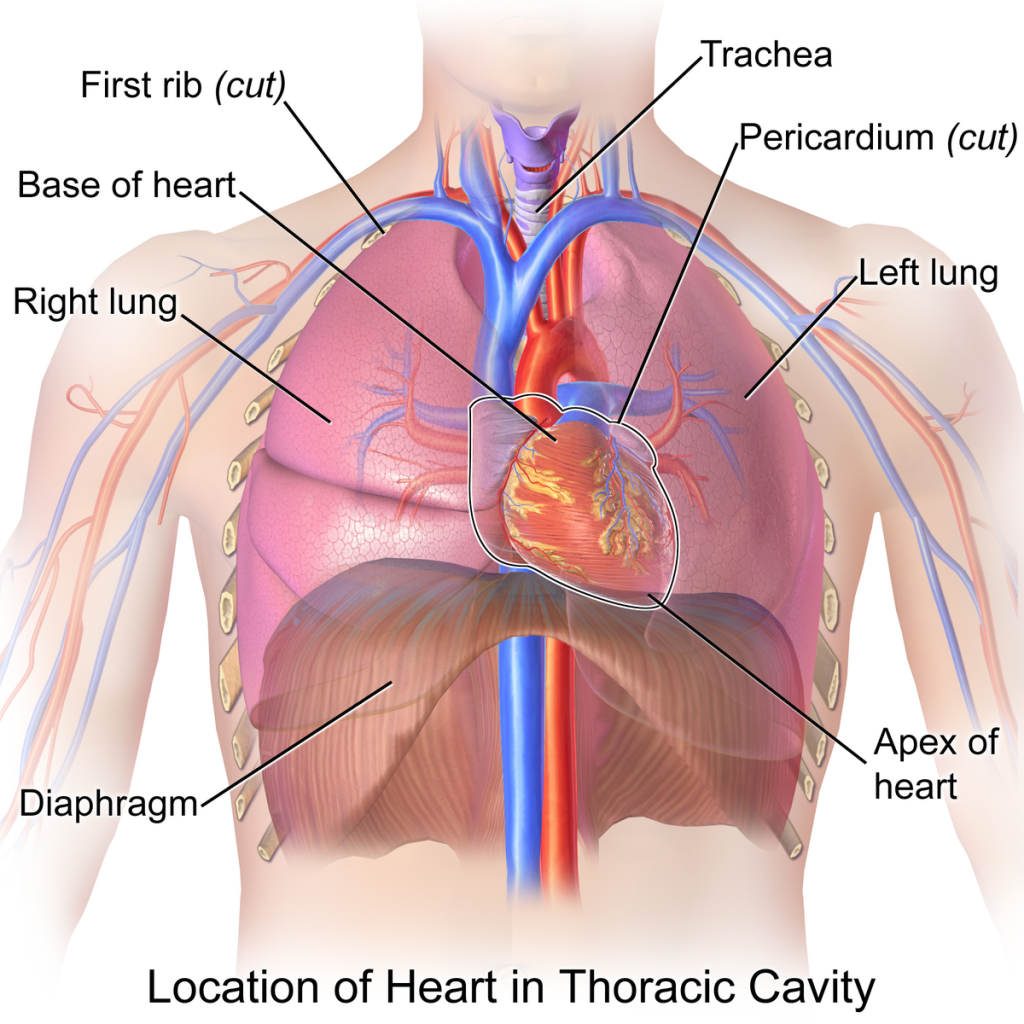

Anatomy of the Chest Cavity

The chest cavity, or thoracic cavity, is the second-largest body cavity and houses vital organs such as the heart and lungs. The thoracic cage, comprising the ribs, sternum, and thoracic vertebrae, provides protection and structure. The diaphragm, a large muscle at the bottom of the thoracic cavity, separates it from the abdominal cavity and plays a crucial role in respiration.

Types of Chest Injuries

Chest injuries are a significant cause of trauma-related deaths in the United States. They are commonly caused by motor vehicle collisions, blunt trauma, and falls. These injuries are categorized into two main types:

- Open Chest Wounds: Result from objects penetrating the chest wall, such as knives, bullets, or fractured ribs that break through the skin.

- Closed Chest Wounds: Occur when the skin remains intact, often due to blunt force trauma.

Common Chest Injuries and Their Management

Blunt Trauma

Blunt trauma results from forceful impact without penetration, such as a blow to the chest. Signs and symptoms include:

- Severe shortness of breath

- Chest pain

- Rapid or irregular pulse

Blunt trauma often leads to associated injuries, such as damage to the spleen, liver, or large blood vessels, which can result in hypovolemic shock due to major blood loss. Immediate medical attention is necessary to manage these complications.

Management:

- Assess for signs of respiratory distress and shock.

- Maintain the patient’s airway and administer oxygen per local protocols.

- Monitor vital signs and prepare for rapid transport to advanced care.

Traumatic Asphyxia

Caused by severe compressive forces, this condition results in a lack of oxygen due to chest trauma. Symptoms include:

- Cyanosis of the head, neck, and shoulders

- Distended neck veins

- Subconjunctival hemorrhage (broken blood vessels in the eyes).

- Bleeding from the nose or ears

- Shock

Management:

- Elevate the patient’s head to reduce pressure.

- Ensure adequate airway and breathing support.

- Provide supplemental oxygen and monitor for associated injuries.

- Rapidly summon advanced medical personnel.

You can learn more by visiting WikiEM’s traumatic asphysxia webpage

Rib Fractures

Rib fractures are usually caused by blunt force. While often not life-threatening, they can result in severe pain and shallow breathing, increasing the risk of complications like:

- Pneumothorax (collapsed lung).

- Hemothorax (blood accumulation in the chest cavity).

- Subcutaneous emphysema (air under the skin).

Management:

- Immobilize the injured area using a pillow or rolled blanket.

- Create additional support with a sling and binder to stabilize the arm on the injured side.

- Monitor for complications such as pneumothorax or hemothorax.

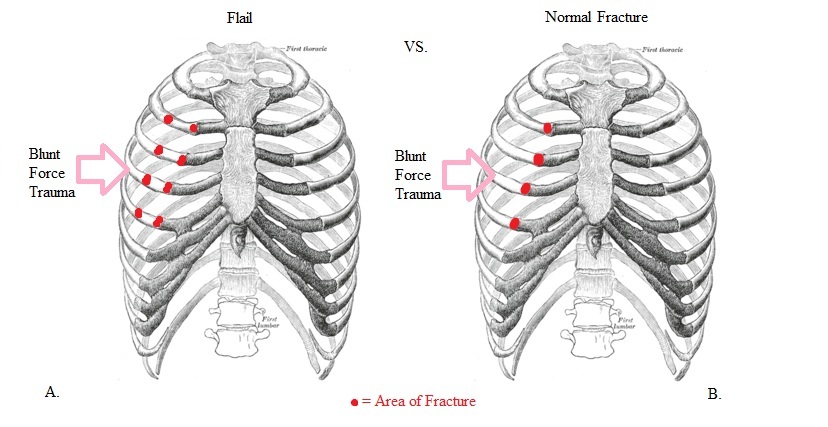

Flail Chest

A flail chest occurs when multiple ribs are fractured in multiple places, creating a loose section of the chest wall that moves independently during breathing.This impairs normal respiration and can be life-threatening.

View the following supplementary YouTube video to see a dramatic example of Flail Chest: Flail chest

Management:

- Support the flail segment with a bulky dressing or pillow.

- Stabilize the area using a sling and binder.

- Administer supplemental oxygen and prepare for rapid transport.

- Monitor for shock.

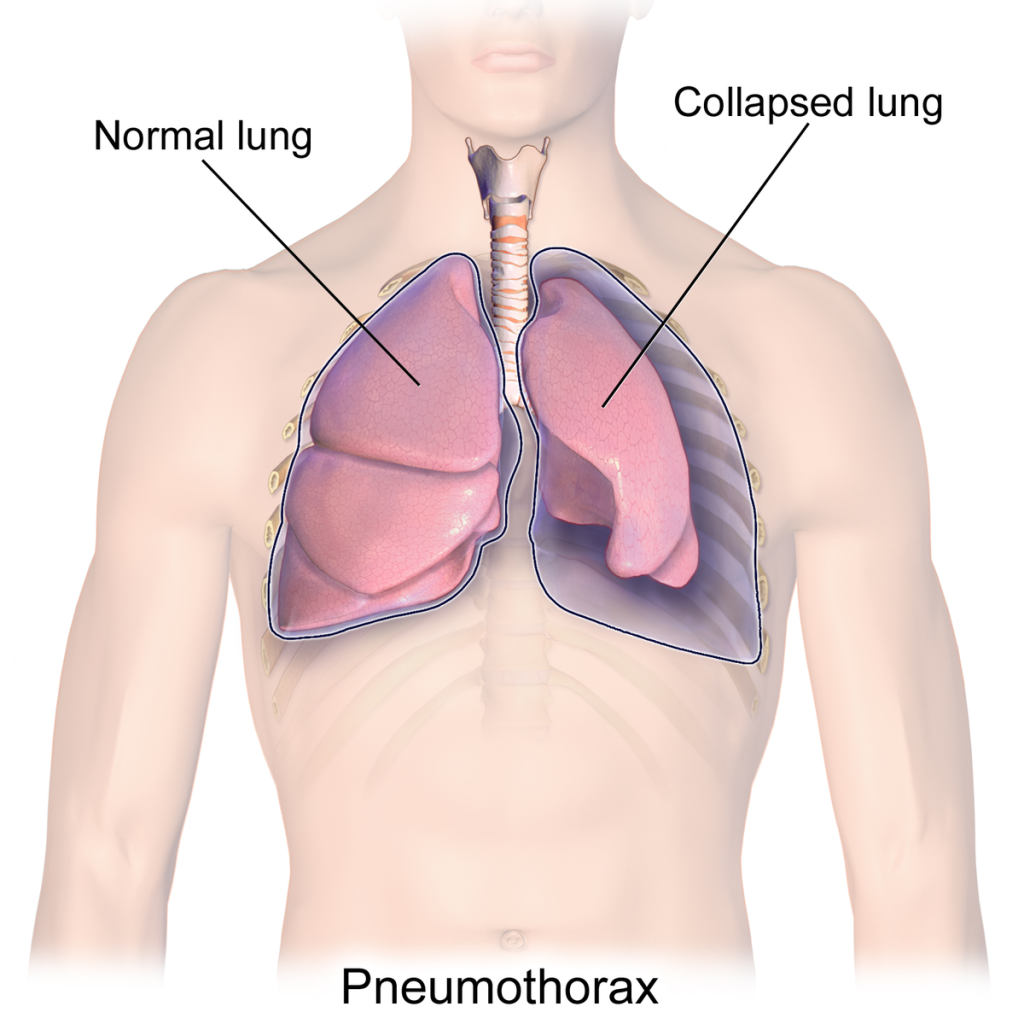

Pneumothorax

A pneumothorax occurs when air enters the chest cavity, collapsing the lung. This can result from blunt trauma or a sucking chest wound. Symptoms include:

- Difficulty breathing.

- Pain at the injury site.

- Diminished breath sounds.

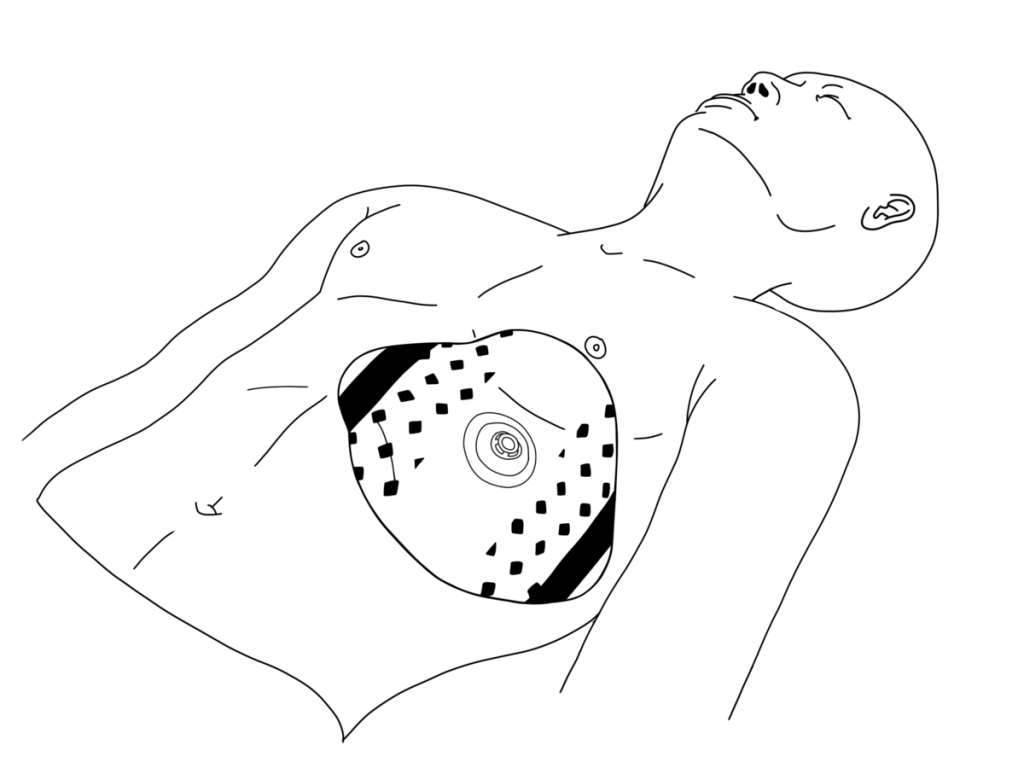

Management:

- If a sucking wound is present, cover it with a sterile gauze dressing, avoiding complete occlusion unless vented chest seals are available.

- Monitor for signs of respiratory distress.

- Provide oxygen as needed.

Hemothorax

A hemothorax involves blood accumulation in the chest cavity, which exerts pressure on the lungs and heart. Symptoms mirror those of pneumothorax but may include:

- Dull percussion sounds over the affected area.

- Abnormal blood pressure.

Management:

- Assess for decreased breath sounds and dull percussion sounds.

- Monitor vital signs and treat for shock.

- Ensure rapid transport to a medical facility.

Tension Pneumothorax

This life-threatening condition occurs when air continues to accumulate in the chest cavity, compressing the lung and major blood vessels. Signs include:

- Severe respiratory distress.

- Jugular venous distension (swollen neck veins).

- Tracheal deviation (a late sign).

Management:

- Recognize signs such as respiratory distress, jugular vein distension (JVD), and tracheal deviation.

- Administer high-flow oxygen and prepare for immediate evacuation.

- Decompression, if required, is performed by advanced medical personnel.

Signs and Symptoms of Chest Injuries

Both open and closed chest injuries can present with the following:

- Shortness of breath and difficulty breathing.

- Pain during breathing or at the injury site.

- Flushed, pale, or bluish skin.

- Distended neck veins.

- Coughing up blood.

- Drop in blood pressure.

Special Situations

Sucking (Open) Chest Wound

Puncture wounds that allow air to enter the chest cavity impair lung function and may cause a sucking sound with breathing.

Management:

- Control bleeding with sterile gauze but avoid completely sealing the wound unless using a vented chest seal.

- Allow air to escape by leaving one side of an occlusive dressing untaped if vented chest seals are unavailable.

- Provide oxygen.

- Monitor for tension pneumothorax and shock.

Impaled Objects

Objects embedded in the chest should not be removed unless they interfere with chest compressions.

Management:

- Stabilize the object with bulky dressings to prevent movement.

- Expose the wound by removing surrounding clothing.

- Apply pressure around the object to control bleeding.

- Secure the dressing in place and monitor for signs of shock.

View the following supplementary YouTube video to see how to handle impaled objects: Impaled Objects with Nick Rondinelli

14.4 Bleeding: An Overview

General Overview of Bleeding

Bleeding occurs when blood escapes from arteries, veins, or capillaries, which may lead to internal or external blood loss. External bleeding is usually visible, making it easier to identify, whereas internal bleeding can be harder to detect. Both types of bleeding can pose life-threatening risks if uncontrolled, as significant blood loss may cause shock and, ultimately, death.

During a primary assessment, it is critical to address severe bleeding before evaluating breathing or pulse. Internal bleeding might only become apparent during a detailed physical exam and patient history.

Key Considerations for Care

When providing care to a bleeding patient, take steps to prevent disease transmission by adhering to the following precautions:

- Use barriers such as latex-free gloves and protective eyewear to avoid contact with blood.

- Avoid touching your face or consuming food or drinks during care.

- Wash your hands thoroughly before (if feasible) and after administering care, even if gloves were worn.

- Replace gloves between patients and disinfect surfaces or equipment exposed to blood.

Recognizing and Responding to Types of Bleeding

Bleeding can originate from arteries, veins, or capillaries, with the following characteristics:

- Arterial Bleeding:

- Bright red blood that spurts in rhythm with the heartbeats.

- High pressure makes it difficult to control.

- The blood flow decreases as blood pressure drops from blood loss.

- Venous Bleeding:

- Dark red blood that flows steadily.

- Typically easier to manage due to lower pressure but can still result in significant blood loss.

- Capillary Bleeding:

- Slow oozing of blood that clots naturally or with minimal direct pressure.

Controlling External Bleeding

To manage external bleeding:

- Cover the wound with sterile gauze and apply direct pressure until the bleeding stops.

- If the dressing becomes saturated, layer additional gauze over the original dressing rather than removing it.

- Maintain firm pressure, and keep the patient warm and positioned flat on their back.

- Always monitor for and address signs of shock, such as pale, cool skin and a rapid pulse.

Nosebleeds

For nosebleeds:

- Position the patient upright with a slight forward tilt to prevent blood from being swallowed.

- Pinch the nostrils for 5–10 minutes.

- Avoid packing the nose, and monitor for shock if bleeding continues.

Life-Threatening Bleeding

For severe bleeding that cannot be controlled with direct pressure, consider:

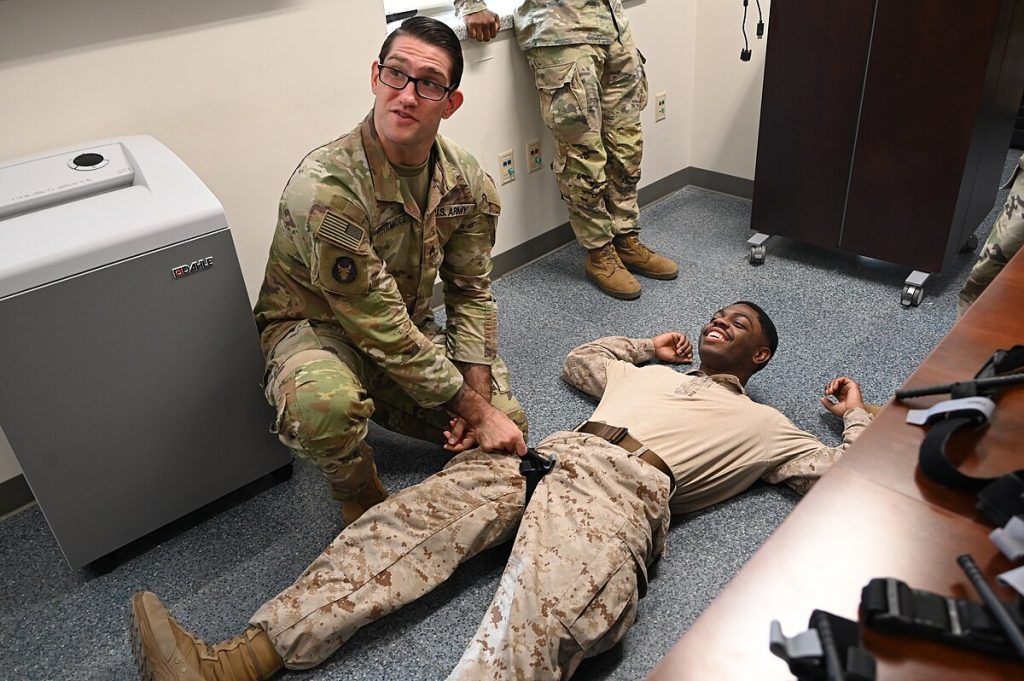

- Tourniquets:

- Apply about 2 inches above the wound (avoiding joints) and tighten until the bleeding stops.

- If the level of the wound is difficult to define, apply the tourniquet “high and tight” on the limb as taught in the military.

- Note the application time and provide this information to emergency personnel.

- Hemostatic Dressings:

- These dressings promote clotting and are used in areas where tourniquets cannot be applied, such as the neck or torso.

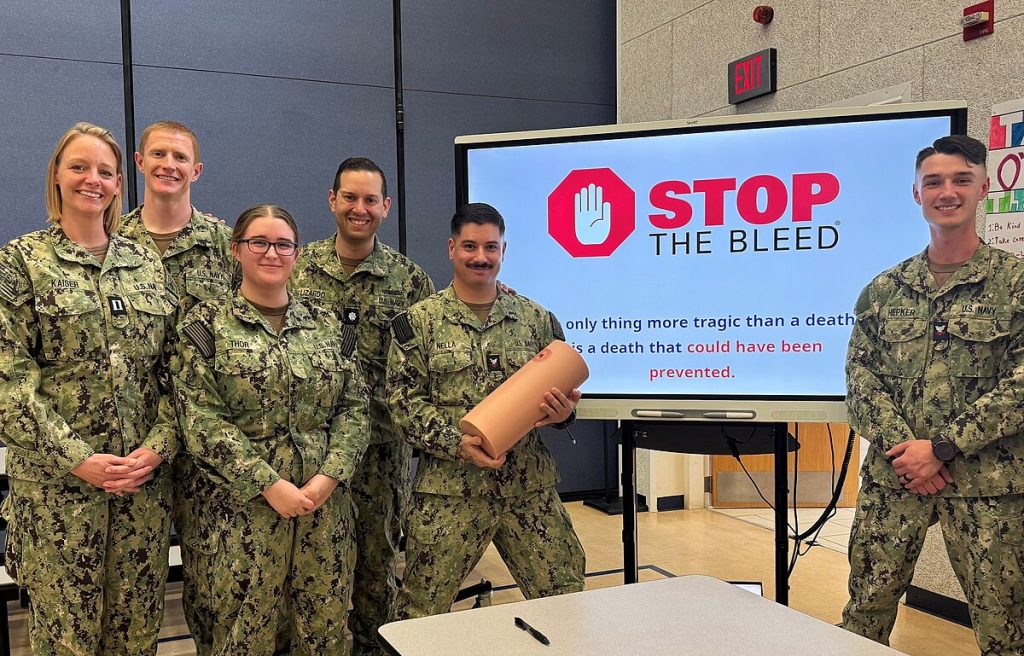

Stop The Bleed

The STOP THE BLEED® campaign was initiated by a federal interagency workgroup convened by the National Security Council Staff, The White House. The purpose of the campaign is to build national resilience by better preparing the public to save lives by raising awareness of basic actions to stop life threatening bleeding following everyday emergencies and man-made and natural disasters. Advances made by military medicine and research in hemorrhage control during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have informed the work of this initiative which exemplifies translation of knowledge back to the homeland to the benefit of the general public.

Visit https://www.stopthebleed.org for more information.

Severe Bleeding Control Considerations:

- Direct Pressure

- Wound Packing

- Tourniquet

Internal Bleeding

Internal bleeding can result from trauma or injuries such as fractures or organ damage. It may not always be visible, but signs include bruising, swelling, nausea, or rapid, weak pulse.

Providing Care:

- Minimize the patient’s movement to reduce blood circulation.

- Address symptoms of shock.

- Call for advanced medical assistance immediately.

14.5 Environmental Emergencies

Environmental emergencies encompass a variety of critical situations, from heat-related conditions like exertional heat stroke to cold-induced injuries such as frostbite. They may also involve encounters with wildlife, like snakebites, or accidents such as drowning. The severity of these emergencies ranges from minor discomfort to life-threatening conditions. For example, while a bee sting may cause mild irritation in one person, it can provoke a severe allergic reaction, such as anaphylaxis, in another.

These emergencies often arise unexpectedly during routine activities. A teenager might find themselves without proper shelter during a sudden downpour on a hike, an older adult may collapse from dehydration during a heatwave, or a small child could drown in a bathtub.

This section will provide you with essential knowledge on recognizing and managing various environmental emergencies, including heat- and cold-related illnesses, bites and stings, anaphylaxis, and drowning.

Understanding Body Temperature Regulation

The human body typically maintains a core temperature of around 98.6°F (37°C). The hypothalamus, located in the brain, acts as the control center for temperature regulation. It monitors changes in blood temperature and adjusts bodily functions to maintain a stable range, typically between 97.8°F and 99°F (36.5°C to 37.2°C). This range is critical for cellular health and function.

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ A simulated person is sweating and looking uncomfortable in the bright sun](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/68/2025/04/aitubo-28-1.jpg)

Mechanisms for Maintaining Warmth

The body generates heat through metabolism—the process of converting food and drink into energy. Physical activity further contributes to heat production. To conserve heat in cold environments, the body constricts blood vessels near the skin’s surface, keeping warmer blood close to vital organs. If this measure is insufficient, shivering begins, producing heat through muscle activity.

Mechanisms for Staying Cool

In hot conditions, the hypothalamus responds by dilating blood vessels near the skin’s surface, allowing heat to dissipate. The body employs five primary cooling methods:

- Radiation: Heat radiates from the body to cooler surroundings without direct contact.

- Convection: Moving air cools the skin by carrying away heat, as in a breeze.

- Conduction: Heat transfers to cooler objects through direct contact, such as sitting on a cold surface.

- Evaporation: Sweat evaporates from the skin, carrying heat away.

- Respiration: Heat exits the body when warm air from the lungs is exhaled.

Populations at Risk

Anyone can experience heat- or cold-related emergencies, but certain groups are more vulnerable:

- Individuals in Extreme Environments: People who work or exercise strenuously in hot, humid, or cold conditions.

- Those With Pre-existing Health Conditions: Chronic illnesses like diabetes or heart disease increase susceptibility. Medications for these conditions may also contribute to dehydration.

- Children and Older Adults: Infants and the elderly may struggle to regulate body temperature effectively.

- Individuals With a History of Temperature-related Issues: Previous heat- or cold-related emergencies increase future risk.

- People With Limited Access to Appropriate Shelter: Poorly insulated homes or lack of cooling systems can heighten risk.

- Those who are Inadequately Hydrated: Dehydration exacerbates susceptibility to temperature extremes.

- Improperly Dressed Individuals: Clothing choices that do not align with environmental conditions can lead to emergencies.

Examples of Environmental Emergencies

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ A simulated person showing discomfort outdoors due to heat](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/68/2025/04/aitubo-29.jpg)

Heat-Related Illnesses

- Heat Cramps: Painful muscle spasms resulting from dehydration and electrolyte loss during intense physical activity.

- Example: A marathon runner develops leg cramps after prolonged exertion on a hot day.

- Care: Rest, rehydration with electrolyte-containing fluids, and gentle stretching.

- Heat Exhaustion: A more severe condition characterized by heavy sweating, weakness, dizziness, and nausea.

- Example: A landscaper becomes lightheaded and weak after hours of work in humid weather.

- Care: Move to a cooler area, hydrate, and seek medical attention if symptoms worsen.

- Heat Stroke: A life-threatening emergency where the body’s cooling mechanisms fail, leading to a dangerously high core temperature.

- Example: An elderly individual collapses during a heatwave without air conditioning.

- Care: Immediate cooling with cold packs, hydration, and emergency medical intervention.

Cold-Related Illnesses

- Frostbite: Freezing of skin and underlying tissues, often affecting extremities like fingers and toes.

- Example: A hiker’s fingers turn pale and numb after being exposed to subzero temperatures.

- Care: Gradual rewarming and medical evaluation.

- Hypothermia: A dangerously low core body temperature caused by prolonged exposure to cold.

- Example: A homeless individual becomes lethargic and confused after a night in freezing weather.

- Care: Remove wet clothing, provide warm blankets, and seek emergency care.

Bites and Stings

- Snakebites: Venomous bites can cause localized pain, swelling, and systemic reactions.

- Example: A gardener is bitten by a rattlesnake while clearing brush.

- Care: Immobilize the limb, keep it below heart level, and transport to a medical facility.

- Bee Stings: May lead to localized swelling or severe anaphylaxis in allergic individuals.

- Example: A child stung during a picnic develops difficulty breathing.

Care: Administer epinephrine for anaphylaxis and seek emergency assistance.

Drowning

- Example: A toddler accidentally falls into a backyard pool and is submerged for several minutes.

Care: Initiate CPR if needed, ensure airway patency, and provide oxygen if available

Recognizing and Responding to Drowning Emergencies

Drowning is one of the leading causes of unintentional injury-related deaths worldwide. It occurs when water obstructs the airway, preventing oxygen exchange. Drowning can happen in various settings, including swimming pools, natural bodies of water, or even shallow bathtubs.

Key Signs of Drowning:

- Inability to call for help due to airway obstruction.

- Quiet struggle, often appearing as if the person is playing or treading water.

- Mouth at water level, alternating between gasping and sinking.

- Arms extended laterally, attempting to push downward for buoyancy.

- Absence of coordinated kicking or visible swimming motions.

- Loss of consciousness if hypoxia persists.

Immediate Actions:

- Ensure Scene Safety: Assess the environment to avoid becoming a victim yourself.

- Rescue: Remove the individual from the water. Use rescue aids if available.

- Basic Life Support:

- Open the airway and check for breathing.

- If absent, begin CPR immediately.

- Provide rescue breaths if trained.

- Activate Emergency Response: Call emergency services promptly.

- Post-Rescue Care: Administer oxygen.

Causes of Drowning

- Traumatic Injury: For example, diving into shallow water can lead to severe injury and drowning.

- Underlying Conditions or Disabilities: Heart disease, seizure disorders, or neuromuscular disorders may cause sudden weakness or loss of consciousness while in the water.

- Mental Health Concerns: Depression, suicide attempts, anxiety, or panic disorders may contribute to drowning incidents.

Severity of Drowning

- Key Factors:

- Duration of submersion and inability to breathe.

- Temperature of the water.

- Outcomes:

- Brain damage or death may begin after 4-6 minutes without oxygen. However, submersion in icy water has led to successful revivals even after prolonged periods.

- Immediate resuscitation increases survival chances and reduces the risk of permanent brain damage.

Signs and Symptoms

- Drowning Incident:

- Persistent coughing.

- Shortness of breath or apnea.

- Disorientation or confusion.

- Vomiting.

- Respiratory and/or cardiac arrest.

- Fatal Drowning:

- Unconsciousness.

- No breathing or pulse.

- Rigor mortis (in later stages).

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ A simulated person is reaching out from the water, face contorted in distress as they appear to be drowning](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/68/2025/04/cuiis0qvaekg00868s3g.jpg)

CPR and emergency interventions are recommended in all cases of drowning, even when the victim appears deceased.

Water Rescue Considerations

- Before the Rescue:

- Assess the patient’s condition, water conditions, and available resources.

- Ensure responders’ safety during the rescue.

- Shallow Water Blackout:

- Caused by voluntary hyperventilation and prolonged breath-holding.

- Leads to unconsciousness before the need to breathe is triggered.

- Instinctive inhalation allows water to enter, initiating the drowning process.

- Preventive measures include educating swimmers on the dangers of hyperventilation.

Water Rescue Techniques

- Prioritize Safety:

- Only attempt rescues if you are a skilled swimmer, trained in water rescue, wearing a personal flotation device (PFD), and accompanied by qualified responders.

- Follow the “reach, throw, row, then go” method:

- Reach with an object (e.g., pole, branch).

- Throw a floating device with a rope if possible.

- Row to the victim using a boat while maintaining distance to avoid capsizing.

- Only go into the water for rescue if properly trained.

Providing Care for Drowning Victims

- Initial Actions:

- Remove the victim from the water while prioritizing airway management.

- Start ventilations in the water if necessary, but chest compressions require removal from the water.

- Use spinal motion restriction if a spinal injury is suspected.

- CPR and Vomiting:

- Be prepared for vomiting, which may occur due to ingested water or forced air during resuscitation.

- Roll the patient to the side to prevent aspiration, and remove vomit using a suction device or finger.

- Hospitalization:

- All drowning victims should be transported to the hospital for monitoring. Complications can develop up to 72 hours post-incident.

Key Considerations

- Environmental Factors:

- Water visibility and depth.

- Temperature and movement of the water.

- Potential hazards like submerged objects or hazardous materials.

- Available Resources:

- Assess the availability of responders, equipment, and personal flotation devices.

Putting It All Together

Environmental emergencies require EMRs to be vigilant and adaptable. Whether managing heat- or cold-related illnesses, venomous bites, or water rescues, EMRs must prioritize patient care while ensuring their own safety.

- Temperature Extremes: Maintaining normal body temperature is critical for cellular function. Early intervention can prevent systemic shutdowns.

- Venomous Bites: Quick and appropriate actions minimize severe reactions.

- Water Rescues: Awareness of personal limits and safety protocols ensures effective assistance without creating additional victims.

Critical Thinking Exercise

Scenario: Snake Bite Reaction

You suspect the snake was venomous, and the patient is exhibiting symptoms of a reaction. Consider the following:

- What immediate care can you provide to minimize the effects of the venom?

- How will you stabilize the patient while waiting for advanced medical help?

- Why is it important to monitor the patient continuously for signs of worsening symptoms?

Understanding these principles equips EMRs to provide effective and life-saving care during environmental emergencies.

14.6 Responding to Head, Neck, and Spinal Injuries: A Practical Guide

Scene Size-Up and Initial Assessment

As an EMR, approaching the scene of a motorcycle crash requires vigilance and a systematic approach. Imagine arriving at the site of a crash where the motorcyclist lies motionless on the road, their helmet still on, while bystanders provide assistance. The motorcycle’s location, far from the driver, hints at the significant force involved.

Key Initial Steps:

- Scene Safety:

- Ensure the area is safe for you, the patient, and others.

- Watch for hazards such as leaking fuel, traffic, or unstable terrain that may pose additional risks.

- Scene Size-Up:

- Assess the mechanism of injury.

- The considerable distance between the motorcycle and the driver strongly suggests severe trauma.

- Primary Assessment:

- Approach the patient carefully, ensuring stabilization of their head and neck to prevent spinal movement.

- Evaluate for life-threatening conditions, focusing on airway obstructions, severe bleeding, or compromised breathing.

Suspected Injuries

Motorcycle crashes frequently result in significant trauma, including:

- Head Injuries:

- These can include open or closed injuries, such as skull fractures or traumatic brain injuries (TBI).

- Spinal Injuries:

- The force of impact may damage the cervical spine, leading to paralysis or other critical complications.

- Additional Trauma:

- Internal bleeding, bone fractures, and soft tissue injuries often accompany these incidents.

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ A simulated person's legs and feet are visible, from where they lie on a wet roadway, with a tipped motorcycle and other vehicles in the background.](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/68/2025/04/cuiobj257d0000802k50.jpg)

Importance of Recognizing Head, Neck, and Spinal Injuries

While injuries to the head, neck, and spine make up a smaller percentage of overall trauma cases, they disproportionately account for fatalities and long-term disabilities. Traumatic brain injury (TBI) alone contributes to approximately 30% of all injury-related deaths in the U.S. annually and results in over 2.5 million emergency department visits.

Common Causes:

- Falls are the leading cause of head, neck, and spinal injuries, particularly in children under 14 and adults over 65.

- Motor vehicle collisions follow as the second leading cause.

- Sports injuries, recreational accidents, and violence also contribute significantly.

Anatomy Review

The head, neck, and spine are complex structures that play critical roles in protecting vital organs and enabling movement:

- Head: Composed of the skull and face, it houses the brain and sensory organs. The cranial cavity shields the brain, while the face includes structures like the cheeks, nose, and jaw.

- Neck: Contains the cervical spine, esophagus, trachea, blood vessels, and muscles. These structures are vital for airway management and circulation.

- Spine: Supports the body and protects the spinal cord. It consists of vertebrae, cartilage, and associated tissues.

Types of Head Injuries

- Open Head Injuries:

- Involve skull fractures or penetrating objects.

- Care includes controlling bleeding with dressings while avoiding pressure over fractures or penetrating objects. Stabilize objects without removing them.

- Closed Head Injuries:

- Result from blunt force trauma. The brain may strike the skull, causing swelling or bleeding without visible external damage.

- Signs include depression or softness on the skull, blood or cerebrospinal fluid leaking from the nose or ears, and changes in consciousness.

Recognizing a Skull Fracture

Suspect a skull fracture when there is significant trauma to the head. Symptoms may include:

- Deformity or swelling.

- Leakage of blood or cerebrospinal fluid.

- Bruising around the eyes (“Raccoon eyes”) or behind the ears (“Battle’s sign”).

- Unequal pupils or facial movement.

View the following supplementary YouTube video to review patient assessment, starting with the Raccoon eyes and Battle’s sign: Never forget patient assessment

Concussion

A concussion is a common form of TBI caused by a bump, blow, or jolt to the head. Symptoms include:

- Confusion, disorientation, or behavioral changes.

- Headache, dizziness, nausea, or sensitivity to light and noise.

- Patients may feel “sluggish” or “not right.”

Management:

- Encourage the patient to stop any activity and seek immediate medical evaluation. Follow-up with a healthcare provider is essential for monitoring and recovery.

Penetrating Wounds

Penetrating wounds occur when objects such as bullets or knives pass through the skull and into the brain.

Management:

- Stabilizing the object with bulky dressings.

- Avoiding direct pressure over fractures, depressions, or areas where bone fragments are visible.

Recognizing a Skull Fracture

Suspect a skull fracture in cases of significant head trauma, even if the injury appears closed. Symptoms may include:

- Visible deformities or swelling.

- Leakage of blood or cerebrospinal fluid from the ears, nose, or scalp.

- Bruising around the eyes (“Raccoon eyes”) or behind the ears (“Battle’s sign”).

- Unequal pupils or facial movement.

Facial Injuries

Clinical Significance

Facial trauma can result from blunt force, penetrating objects, falls, motor vehicle collisions, or assaults. The face is highly vascular, and even minor injuries can produce heavy bleeding. Additionally, injuries near the mouth, nose, or jaw can rapidly compromise the airway.

Assessment

- Use DACP-BTLS for systematic inspection: Deformities, Abrasions, Contusions, Punctures/Penetrations, Burns, Tenderness, Lacerations, Swelling.

- Check for:

- Soft-tissue swelling or deformity

- Heavy bleeding from the mouth, nose, or lacerations

- Missing or broken teeth (risk for aspiration)

- Jaw dislocation or fracture (malalignment, difficulty speaking)

- Impaled objects (evaluate airway risk)

- Be alert for signs of airway compromise: gurgling, stridor, absent breath sounds, or excessive bleeding.

Management:

- Maintain a patent airway:

- Use suction if blood or vomit obstructs the airway.

- Avoid NPAs if midface trauma or suspected skull fracture is present.

- Use OPA only if no gag reflex is present.

- Control bleeding with gentle but firm pressure.

- Avoid pressure over suspected fractures.

- Stabilize impaled objects unless they obstruct the airway.

- Reposition the patient to drain fluids safely if airway control is threatened.

EMR Tip: Always prepare for airway deterioration in facial trauma. Suction and proper patient positioning are key to survival.

Eye Injuries

Clinical Significance

Eye injuries, though often isolated, can lead to blindness or significant anxiety. They require precise care to avoid worsening the injury.

Assessment

- Determine the mechanism: chemical splash, blunt trauma, penetrating object, or foreign body.

- Observe for:

- Tearing, redness, vision changes, swelling

- Abnormal pupil size or reactivity

- Impaled objects—do not remove

Management:

- For chemical exposures:

- Irrigate with normal saline or water for at least 15–20 minutes, flushing from the inside corner outward.

- For loose foreign bodies:

- Flush gently with saline if not embedded.

- Never attempt to remove embedded material.

- For blunt or penetrating trauma:

- Avoid pressure on the globe.

- Stabilize any protruding object with a rigid shield or cup.

- Cover both eyes to prevent movement.

EMR Tip: Covering both eyes reduces sympathetic movement. Reassure the patient throughout care, as vision loss causes extreme distress.

Neck and Spinal Cord Injuries

Clinical Significance

Neck and spinal cord injuries carry a high risk of permanent disability or death due to airway compromise, neurogenic shock, or paralysis. Cervical spine injuries, particularly above C5, may impair diaphragm function and threaten breathing. EMRs must act immediately to protect the spinal cord from further injury.

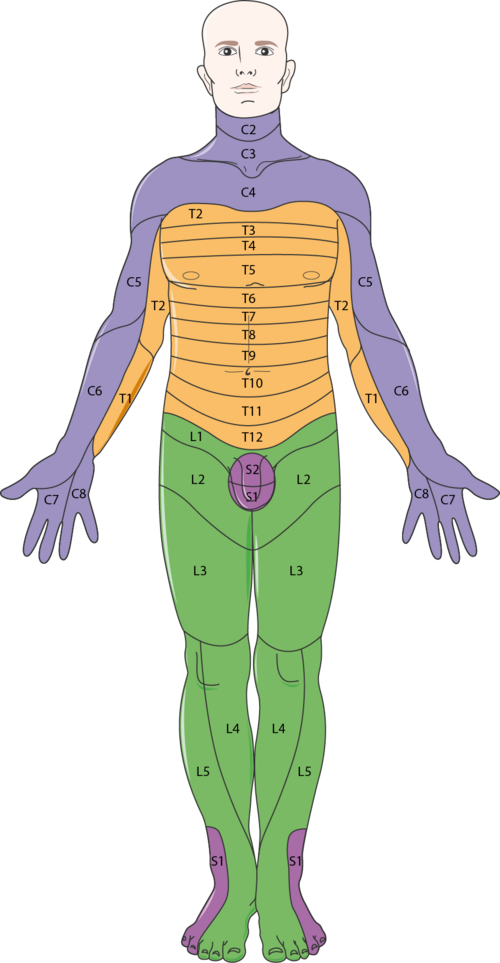

Relevant Anatomy

- Spinal column segments:

- Cervical (C1–C7): Most vulnerable; injuries may impair breathing and movement.

- Thoracic (T1–T12): Protected by ribs, but injuries can impact trunk stability.

- Lumbar (L1–L5): Susceptible in falls and lifting injuries.

- Sacrum/Coccyx: Rarely causes spinal cord damage, but painful.

- Spinal cord function:

- Transmits sensory and motor signals.

- Ends around L1–L2 (conus medullaris).

- Damage may cause quadriplegia, paraplegia, or autonomic dysfunction.

Mechanism of Injury (MOI)

- Significant MOI examples:

- High-speed crashes, ejections

- Falls >10 feet

- Motorcycle crashes >20 mph

- Diving accidents

- Axial loading (fall onto head)

- Penetrating trauma to the head, neck, or back

- Spinal motion risk types:

- Compression (axial loading)

- Flexion/extension (whiplash)

- Rotation

- Distraction (hanging)

- Lateral bending

- Penetrating injury

Spinal Injury Assessment

- Initiate manual in-line stabilization immediately.

- Airway: Use jaw-thrust maneuver to open the airway.

- Breathing: Watch for shallow or inadequate respirations (C3–C5 injury).

- Circulation: Manage shock without excessive manipulation.

- Conduct a focused neurological exam:

- Ask: “Can you move your fingers and toes?” “Can you feel me touching them?”

- Check grip strength, foot push, and sensation

- Evaluate for:

- Numbness or tingling

- Weakness or paralysis

- Incontinence

- Priapism (sign of cord injury)

Spinal Motion Restriction (SMR)

Cervical Collar

- Select based on patient’s size and anatomy.

- Do not obstruct airway or apply to unstable necks without support.

- If unavailable or unsuitable, use towel rolls and manual support.

View the following YouTube video for a review of sizing and placement of a cervical collar: Cervical Collar Application

Stabilization Devices

- Long spine boards: Used for movement only; pad voids and secure head last.

- Maintain manual stabilization throughout until fully secured or transferred to the transport stretcher.

Emergency Medical Care

- Scene Safety: Stabilize the environment and access safely.

- Primary Survey:

- Use jaw-thrust, not head-tilt.

- Support airway and breathing.

- Control bleeding with caution.

- Secondary Survey:

- Complete head-to-toe assessment.

- Reassess CMS after every movement.

- ALS Backup:

- Call for advanced support if:

- Mental status changes

- Ventilatory failure

- Multisystem trauma

- Call for advanced support if:

Complications of Spinal Cord Injury

- Neurogenic shock: Low BP, slow HR, warm skin—seen in high cord injuries.

- Respiratory compromise: Especially above C5.

- Permanent paralysis

- Secondary cord injury from poor immobilization

Special Considerations

Helmet Removal

- Only if:

- Airway compromised

- Cannot immobilize with helmet in place

- Patient is in cardiac arrest

- Remove with two trained providers. Retain helmet for transport with the patient.

View the following YouTube video for a review of removing a helmet and placing a cervical collar: Helmet Removal

Pediatrics

- Pad under shoulders for neutral alignment.

- Use a pediatric-sized collar or improvisation.

Geriatrics

- Handle gently.

- Pad spinal curves and consider brittle bones or arthritic changes.

Rapid Extrication

- Use only if:

- Scene is unsafe

- Life-threatening condition demands movement

- Access to another critical patient is blocked

Summary for EMRs

- Suspect spinal injury with any head, neck, or torso trauma.

- Perform continuous manual stabilization until immobilized.

- Reassess CMS frequently.

- Protect the airway and provide oxygen if needed.

- Collaborate with ALS when injury severity exceeds EMR capabilities.

References

American Red Cross. (2017). Emergency medical response.

Le Baudour, C., Wesley, K., & Bergeron, J. D. (2019). Emergency medical responder: First on scene (11th ed.). Pearson.

Le Baudour, C., Laurélle, K., & Wesley, K. (2024). Emergency medical responder: First on scene (12th ed.). Pearson.

Images:

Figure 14.1: “US_Army_Vet_Injury” by Wes Washington is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Figure 14.2: ”Blausen_0458_Heart_ThoracicCavity” by Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014 is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Figure 14.3: ”Flail_chest_vs._Normal_chest_fracture” by Mrnave is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Figure 14.4: ”Blausen_0742_Pneumothorax” by Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014 is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Figure 14.5: ”Vented-chest-seal” by Baedr-9439 is licensed under CC0, Public Domain

Figure 14.6: ”Direct-pressure-and-elevation” by Mike6271 is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 14.7: “Nosebleed” by Mark Schwartz, Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Figure 14.8: ”Tourniquet” by Mark Schwartz, Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Figure 14.9: ”Hemostatic_Agent_3” by Intropin (Mark Oniffrey) is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 14.10: “Naval_Hospital_Sigonella_STEM_Team_Hosts_Life-Saving_“Stop_the_Bleed”_Training_for_DoDEA_Educators_(8986352)” by Chiara Caputo, US Navy is in the Public Domain. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

Figure 14.11: “STOP_THE_BLEED_Course_(8209643)” by Staff Sgt. Juan Paz, US Air Force is in the Public Domain. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

Figure 14.12: “STOP_THE_BLEED_Course_(8209650)” by Staff Sgt. Juan Paz, US Air Force is in the Public Domain. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

Figure 14.13: “STOP_THE_BLEED_Course_(8209651)” by Staff Sgt. Juan Paz, US Air Force is in the Public Domain. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

Figure 14.14: “STOP_THE_BLEED_Course_(8209647)” by Staff Sgt. Juan Paz, US Air Force is in the Public Domain. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

Figure 14.15: Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/

Figure 14.16: Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/

Figure 14.17: “Stechende_Biene_12a” by Waugsberg is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Figure 14.18: ”Baltimore_District_hosts_water_rescue_simulation_at_Hammond_Lake,_Pa._(9685980493)” by U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is licensed under CC BY 2.0. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

Figure 14.19: Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/

Figure 14.20: Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/

Figure 14.21: “Ramstein_takes_action_alongside_host_nation_agencies_141018-F-IQ718-005” by Senior Airman Hailey Haux, US Air Force is in the Public Domain. The appearance of U.S. Department of Defense (DoD) visual information does not imply or constitute DoD endorsement.

Figure 14.22: “Nervous_system_-_Dermatomes_1_–_Smart-Servier” by Smart Servier website: Nervous system is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Videos:

International Emergency Medicine Education Project. (2018, July 14). Flail chest [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=gtMcEQSfje4

Heart2Heart CPR – First Aid 4 Real. (2008, November 10). Impaled Objects with Nick Rondinelli [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=yT4WirKxmuw

The Paramedic Coach. (2022, April 18). Never forget patient assessment [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/MSdKLorVhmU?si=r06Lk98PbGT0mJCI&t=126

San Diego Miramar EMT Program. (2020, August 12). Cervical collar application [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CtL9ukCCY9I

San Diego Miramar EMT Program. (2020, August 12). Helmet removal [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=tDTMIid7zA4