Chapter 16: Special Patient Populations

Suzanne Martens, MD, FACEP, FAEMS, MPH, EMT

16.1 Introduction

Learning Objectives

- Gynecology

- Obstetrics

- Neonatal care

- Patients with special challenges

16.2 Gynecology for the Emergency Medical Responder

EMRs must be prepared to respond to calls involving female patients experiencing gynecologic emergencies. These situations may involve abdominal or pelvic pain, vaginal bleeding, emotional trauma, or a combination of these. In some cases, the patient may be dealing with a chronic condition, while in others, the situation may be sudden and life-threatening. Additionally, some emergencies involve not only physical but also psychological and legal components, such as in cases of sexual assault.

What sets gynecologic emergencies apart is the need for increased sensitivity, discretion, and compassion. These calls often involve intimate areas of the body and deeply personal health issues. As such, EMRs must demonstrate professionalism, maintain patient dignity, and conduct assessments with care. A strong foundation in anatomy and pathophysiology is essential to correctly interpret symptoms and initiate the appropriate response.

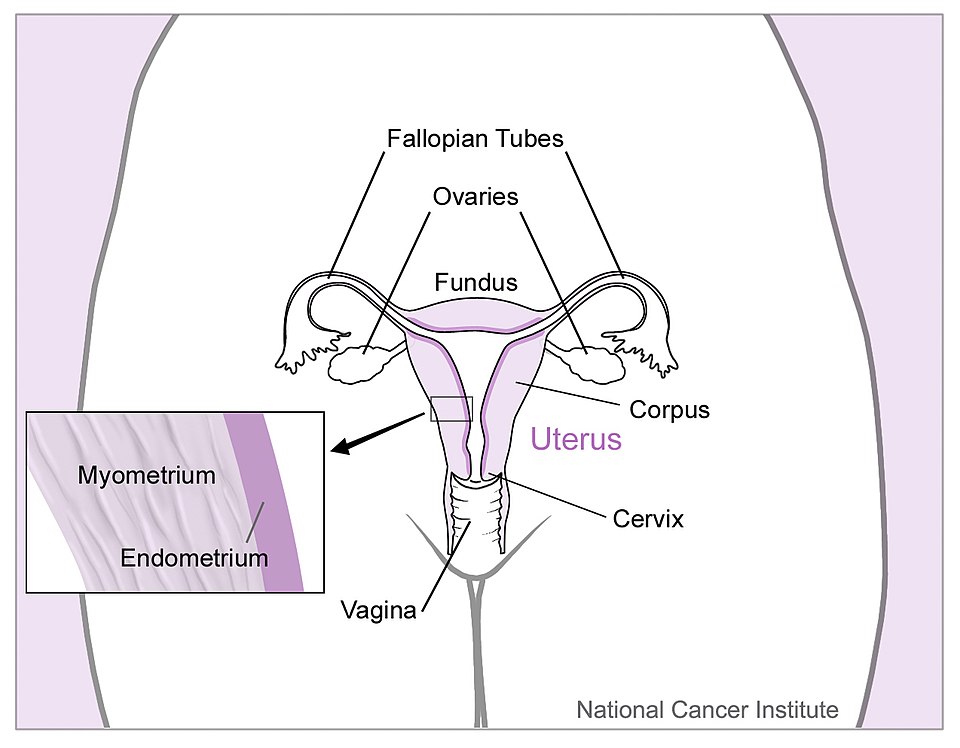

Anatomy and Physiology of the Female Reproductive System

The female reproductive system is responsible for producing eggs (ova), facilitating fertilization, supporting fetal development during pregnancy, and regulating the menstrual cycle. Understanding this anatomy helps EMRs determine the potential source of a patient’s complaint and assess whether the condition may be serious.

Ovaries: Two almond-shaped glands located on either side of the uterus. They contain thousands of immature ova and are responsible for releasing one mature egg each month (ovulation). They also produce the hormones estrogen and progesterone, which regulate the menstrual cycle and support pregnancy.

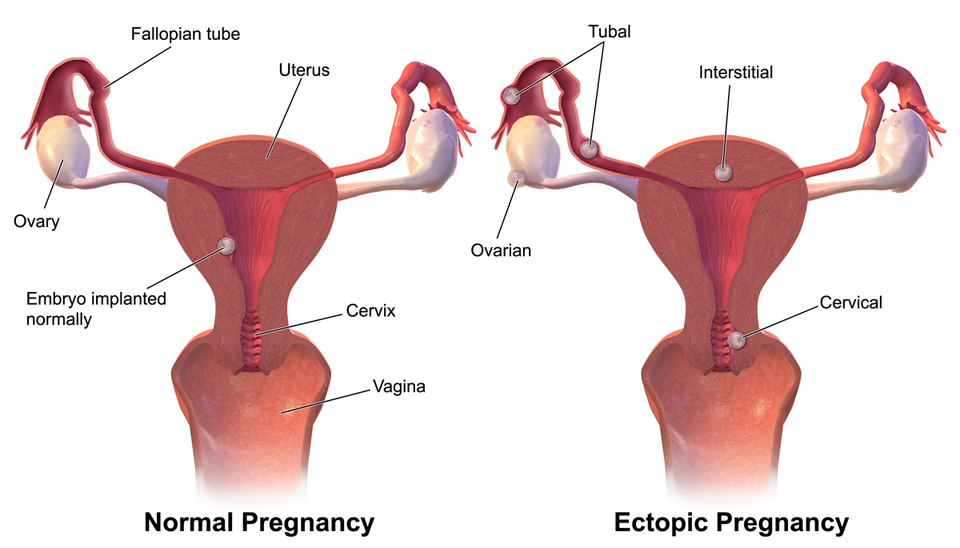

Fallopian Tubes: Narrow, muscular tubes that connect the ovaries to the uterus. After ovulation, the egg travels through one of these tubes. Fertilization by a sperm cell typically occurs here. If a fertilized egg implants in the fallopian tube, this leads to an ectopic pregnancy—a life-threatening emergency.

Uterus: A thick-walled, muscular organ located in the center of the pelvis. During each cycle, the uterine lining thickens in preparation for pregnancy. If no fertilized egg implants, the lining is shed as menstrual blood. The uterus also contracts during labor to deliver the baby.

Cervix: The lower, narrow portion of the uterus that opens into the vagina. It acts as a gateway, remaining tightly closed during most of the menstrual cycle and pregnancy, but dilating during childbirth.

Vagina: A muscular, elastic canal that connects the cervix to the external genitals. It serves as the birth canal and the passageway for menstrual blood and sexual intercourse. Its proximity to the urinary and digestive systems can sometimes complicate the identification of abdominal or pelvic pain.

Understanding how these organs interact helps EMRs consider possible causes when a female patient presents with symptoms like pain, abnormal bleeding, or signs of infection.

Pathophysiology of Gynecology-Related Emergencies

Gynecologic emergencies can arise from structural, hormonal, or traumatic causes. Many conditions can produce overlapping symptoms such as pelvic pain or vaginal bleeding, so obtaining a thorough history and observing for signs of distress is crucial. EMRs are not expected to diagnose these conditions but should recognize when rapid transport is necessary.

Ovarian Cysts: Ovarian cysts are fluid-filled sacs that develop on the ovaries, often as part of the normal ovulation cycle. While most are harmless and go unnoticed, larger cysts can twist (ovarian torsion) or rupture. A ruptured cyst can cause sudden, severe abdominal pain and may lead to internal bleeding. This can mimic appendicitis or ectopic pregnancy. Patients may appear pale, dizzy, or in shock if bleeding is significant.

Endometriosis: This chronic condition involves endometrial tissue growing outside the uterus, often on the ovaries, fallopian tubes, or pelvic walls. It responds to the menstrual cycle just like uterine tissue, causing inflammation and scarring over time. Symptoms include severe menstrual cramps, pelvic pain, pain during intercourse, and sometimes infertility. Though not typically life-threatening, the pain can be intense and debilitating.

Non-Traumatic Vaginal Bleeding: This refers to abnormal vaginal bleeding not caused by injury. It may stem from hormonal imbalances, uterine fibroids, polyps, miscarriage, or even malignancy. While some causes are benign, others—especially in pregnant women—can be life-threatening. Heavy or prolonged bleeding may lead to hypovolemic shock. For EMRs, estimating the amount of blood lost, identifying signs of shock, and determining pregnancy status are key steps.

Sexual Assault: Sexual assault is both a medical emergency and a deeply personal trauma. Victims may present with emotional distress, genital or other bodily injuries, or signs of psychological shock. Some may be frightened, withdrawn, or reluctant to speak. EMRs should never interrogate or attempt to investigate. Instead, they should focus on ensuring safety, providing emotional support, and preserving any potential forensic evidence.

Assessment and Interventions for Gynecology-Related Emergencies

Gynecologic emergencies require a high degree of professionalism and communication. Patients are often in pain and may feel embarrassed, anxious, or vulnerable. EMRs must focus on providing respectful care while identifying life-threatening conditions and initiating transport as needed.

General Assessment Guidelines:

- Ensure scene safety and patient privacy.

- Request a female provider if available, especially for sensitive exams.

- Explain procedures clearly and obtain verbal consent.

- Use open-ended questions to gather history:

- When did the symptoms start?

- Where is the pain located?

- When was your last menstrual period (LMP)?

- Is there any chance you could be pregnant?

- Observe for signs of shock (pale skin, rapid pulse, hypotension).

Condition-Specific Assessment and Intervention

Ovarian Cysts

- Assessment: Sudden, sharp pain in one lower quadrant; may report dizziness or fainting if ruptured.

- Intervention: Monitor for internal bleeding which may cause hypotension or shock, provide reassurance, minimize movement, and initiate rapid transport.

Endometriosis

- Assessment: Chronic pelvic pain, worsens during menstruation; may report painful intercourse or bowel movements.

- Intervention: Offer supportive care and transport for definitive management.

Non-Traumatic Vaginal Bleeding

- Assessment: Volume and duration of bleeding; presence of clots or tissue; possible pregnancy.

- Intervention: Place absorbent pads to monitor blood loss; position patient supine or left side (if obviously pregnant); treat for shock; rapid transport.

Sexual Assault

- Assessment: Observe demeanor and physical state without probing for details.

- Intervention: Protect privacy; avoid touching or moving the patient’s clothes unless necessary; involve law enforcement and/or Sexual Assault Response Team; transport to an appropriate facility for care and forensic evaluation.

16.3 Obstetrics

Caring for pregnant patients in the prehospital setting is both a privilege and a responsibility. A pregnant patient represents not just one life, but two. Medical emergencies during pregnancy can escalate rapidly, and delays in recognition or treatment can have serious consequences for both the mother and the unborn child. EMRs play a vital role in the early recognition and stabilization of these patients.

This chapter introduces the essential anatomy and physiology of pregnancy, the changes a woman’s body undergoes, and the unique emergencies that may occur. It also equips EMRs with focused assessment strategies and the skills to provide safe and effective emergency care for pregnant women.

Anatomy and Physiology of Pregnancy, the Menstrual Cycle, and the Prenatal Period

Understanding how the female reproductive system functions—and how it changes during pregnancy—is key to assessing and managing obstetric calls.

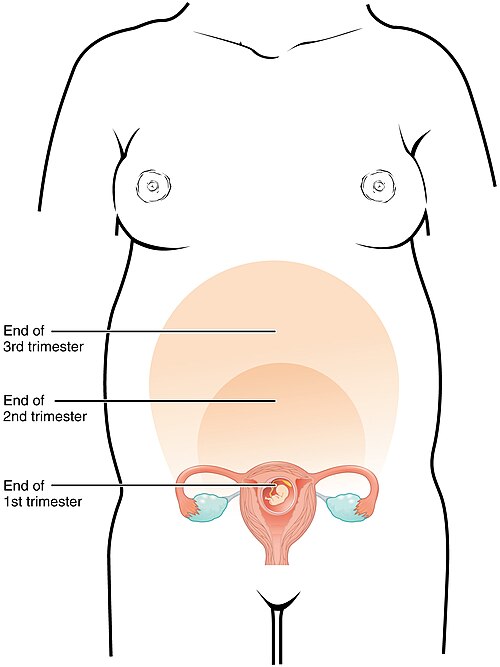

Female Reproductive Anatomy During Pregnancy

- Fetus: The developing baby, which grows within the uterus. Begins as an embryo and is referred to as a fetus after 8 weeks of gestation.

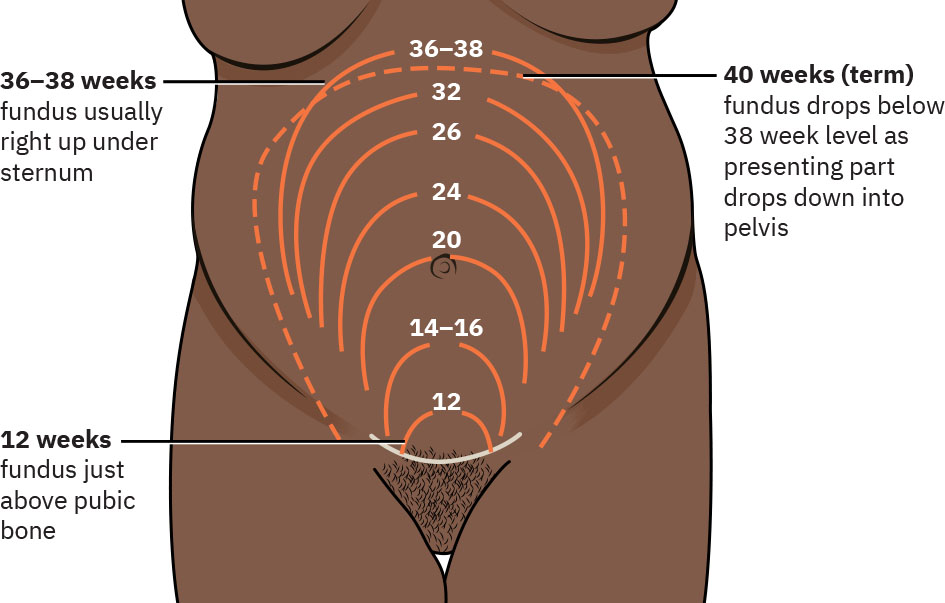

- Uterus and Fundus: The uterus expands dramatically during pregnancy. The fundus, or top of the uterus, becomes a useful landmark to estimate fetal age and progression of pregnancy. It rises above the pubic bone around 12 weeks, the umbilicus around 20 weeks, and near the xiphoid process near full term (36–40 weeks).

- Cervix: The lower, narrow end of the uterus that remains closed during most of the pregnancy. It softens and begins to dilate in preparation for childbirth.

- Placenta: A vital organ that attaches to the uterine wall and acts as the interface between the mother and fetus. It transfers oxygen and nutrients and removes waste through the umbilical cord. It is also a site of hormone production necessary for sustaining pregnancy.

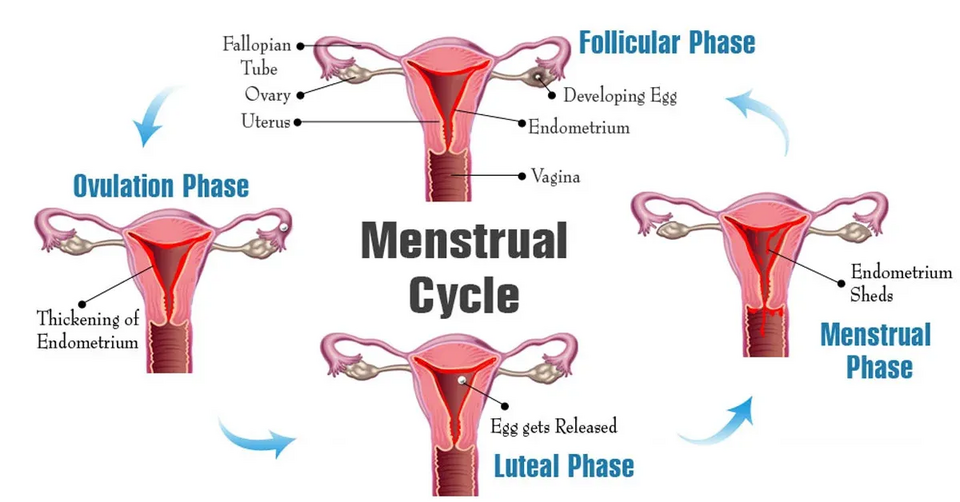

The Menstrual Cycle

The menstrual cycle prepares the female body for pregnancy. It involves coordinated hormonal signaling between the brain and ovaries, leading to ovulation and changes in the uterine lining.

- Typical Cycle Length: 28 days

- Ovulation: Around day 14—an egg is released.

- If Fertilization Does Not Occur: Hormone levels drop, and the uterine lining is shed (menstruation).

Prenatal Period and Gestation

- Prenatal Period: The time from conception to birth.

- Gestational Age: Measured in weeks from the first day of the last menstrual period (LMP).

- Trimester Divisions:

- First Trimester (0–13 weeks): Organ formation; highest risk of miscarriage.

- Second Trimester (14–26 weeks): Rapid fetal growth.

- Third Trimester (27–40 weeks): Final maturation and preparation for birth.

Anatomical and Physiological Changes During Pregnancy

Pregnancy affects nearly every organ system. Understanding these changes helps explain why pregnant patients may present with symptoms that differ from non-pregnant individuals and helps EMRs interpret vital signs and physical findings accurately.

Reproductive System

- Uterus grows from a pelvic organ to fill much of the abdominal cavity.

- Increased blood flow to the uterus (about 20% of cardiac output by term).

- Cervical changes include softening and mucus production to protect the fetus.

Respiratory System

- Oxygen demand increases by 15–20%.

- Diaphragm elevates, reducing lung capacity.

- Respiratory rate increases.

- Increased metabolism with decreased thoracic area results in decreased respiratory reserve.

- Pregnant women may feel short of breath even at rest.

Cardiovascular System

- Blood volume increases by up to 50%, supporting both mother and fetus.

- Heart rate increases by 10–15 bpm.

- Mild relative anemia is common due to increased plasma volume.

- Blood pressure often decreases slightly in the second trimester, then returns to baseline.

Gastrointestinal System

- Slower digestion due to hormonal effects.

- Nausea and vomiting are common, especially in the first trimester.

- Delayed gastric emptying increases risk of aspiration in unconscious patients.

- Try to keep head elevated.

Urinary System

- Kidney function increases to manage metabolic waste for two.

- Uterus compresses the bladder, leading to frequent urination.

Musculoskeletal System

- Joints become more flexible due to the hormone relaxin.

- Center of gravity shifts forward, increasing fall risk.

Medical Emergencies of the Pregnant Female

Pregnant women are at risk for several medical conditions that are either caused by pregnancy or exacerbated by it. Early recognition and timely transport are critical.

Hyperemesis Gravidarum

- Severe, persistent vomiting that goes beyond normal morning sickness.

- Can cause dehydration, weight loss, and electrolyte imbalance.

- May require hospitalization and IV fluids.

Gestational Diabetes

- Occurs in about 6% of pregnant women in the second half of pregnancy.

- Does not mean they will continue to be diabetic.

- Be alert for both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia in pregnant women.

Seizures in Pregnancy

- May be due to epilepsy, trauma, or pregnancy-related conditions (e.g., eclampsia).

- Protect airway and patient from injury.

- Consider high-flow oxygen and prepare for potential complications.

Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension (PIH)

- High blood pressure developing after 20 weeks gestation.

- May be a precursor to preeclampsia.

Preeclampsia

- Characterized by high BP (above 140/90 mmHg), swelling (edema), and protein in urine.

- Symptoms may include headaches, vision changes, and abdominal pain.

- Can progress to eclampsia, involving seizures—an obstetric emergency.

Supine Hypotension Syndrome

- Gravid uterus compresses the inferior vena cava when patient lies flat.

- Reduces venous return, causing dizziness or hypotension.

- Position the patient on left side to relieve compression.

Hemorrhagic Antepartum Emergencies

Vaginal bleeding during pregnancy may be a warning sign of serious complications, particularly in the second or third trimester.

Spontaneous Abortion (Miscarriage)

- Occurs before 20 weeks.

- The most common complication of pregnancy in the U.S., experienced in 20% of pregnancies.

- Signs include vaginal bleeding, cramping, and passage of tissue.

- Emotional support is crucial in addition to physical care.

- There is little or nothing that can be done to cause or resolve the reason for bleeding.

- Positive support of the patient is key.

Ectopic Pregnancy

- Fertilized egg implants outside the uterus (commonly in the fallopian tube).

- Occurs in about 1–2% of pregnancies in the U.S.

- Can rupture, leading to severe internal bleeding.

- Symptoms include sharp lower abdominal pain, shoulder pain (referred pain), and signs of shock.

- Early in pregnancy, first trimester.

- Surgical emergency.

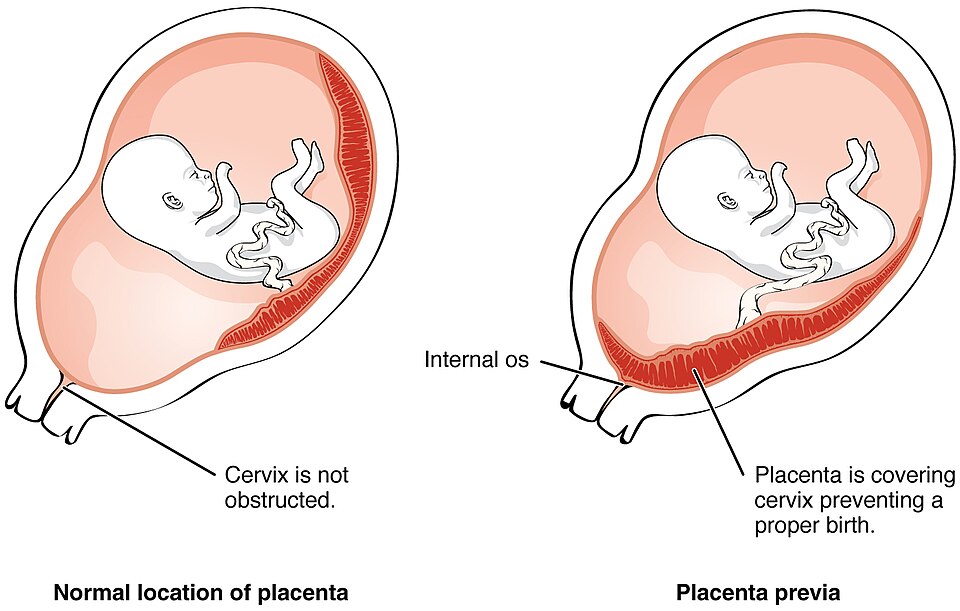

Placenta Previa

- Placenta partially or fully covers the cervix.

- Painless, bright red bleeding in late pregnancy.

- Do not perform vaginal exams; transport carefully.

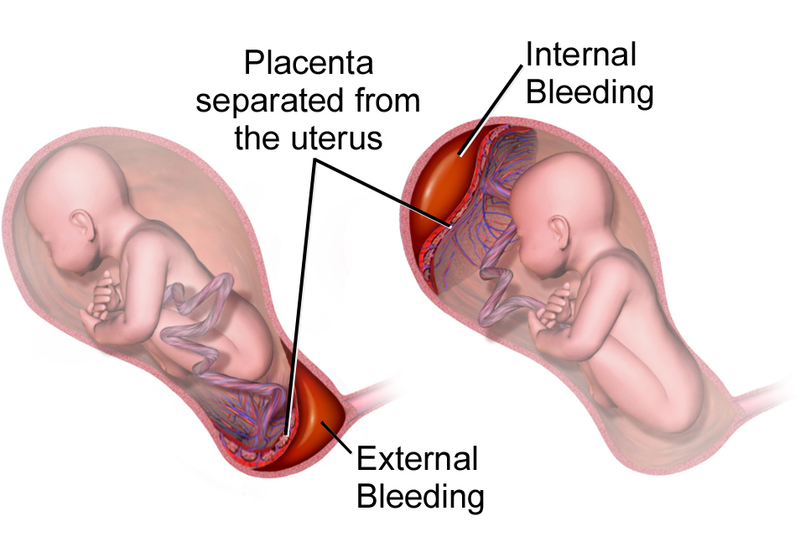

Abruptio Placentae

- Premature separation of placenta from uterine wall.

- Painful, dark red bleeding; may have signs of fetal distress or maternal shock.

- Requires immediate transport and ALS support if available.

Ruptured Uterus

- Rare but catastrophic.

- Risk factors include trauma or previous C-section scars.

- Symptoms include sudden pain, cessation of contractions, and shock.

Pregnancy-Specific Assessment and Emergency Care

EMRs must adjust their assessment techniques and interventions to account for pregnancy-related changes.

Scene Size-Up

- Assess for hazards.

- Look for signs of trauma, blood, or childbirth in progress.

- Request ALS or additional transport if needed.

Primary Assessment

- Focus on ABCs with modifications for pregnancy.

- Position patient on left side to improve circulation after 20 weeks.

- At 20 weeks gestation the uterus rises to the level of the umbilicus.

- Monitor for signs of hypoxia, shock, or altered mental status.

Secondary Assessment

- Obtain SAMPLE history.

- Ask pregnancy-specific questions:

- When was your last menstrual period (LMP)?

- How many weeks pregnant are you?

- Have you had any prenatal care?

- Are there fetal movements?

- Is there any bleeding or fluid loss?

Determine Gestational Age by Fundal Height

- Fundus at:

- 12 Weeks: Just above the pubic bone.

- 20 Weeks: At the level of the umbilicus.

- 36–40 Weeks: Near the xiphoid process.

Emergency Medical Care

- Airway: Ensure patency; use OPA/NPA if needed.

- Breathing: Administer high-flow oxygen.

- Circulation: Control bleeding, treat for shock (position on left side, keep warm, oxygen).

- Vaginal Bleeding: Place sanitary pads to estimate blood loss. Do not pack the vagina.

- Reassessment: Monitor vital signs and fetal movement regularly. Adjust care based on patient stability.

16.4 Normal Labor and Delivery

EMRs are often the first healthcare professionals to arrive during labor, sometimes unexpectedly assisting in childbirth outside the hospital. While labor is a normal physiological process, complications can arise quickly, and the ability to recognize labor stages and support delivery is essential.

This chapter will help EMRs understand the progression of labor, identify when delivery is imminent, and provide step-by-step guidance for assisting a normal prehospital birth—ensuring safety for both mother and newborn.

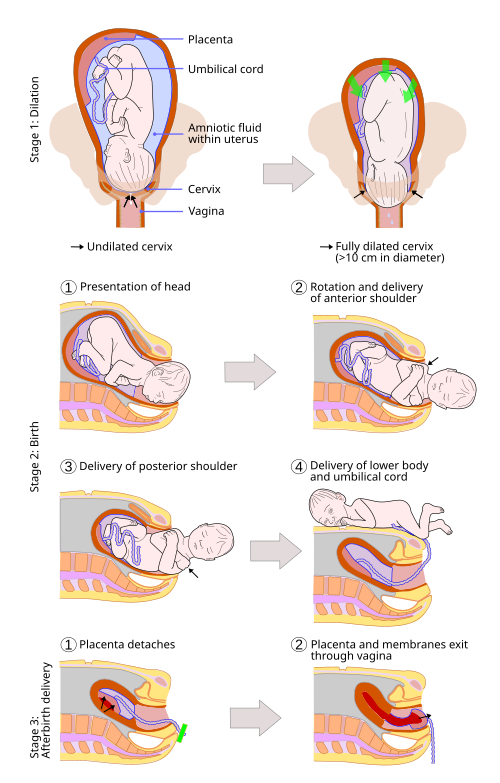

Stages of Labor

Labor is divided into three stages, each with distinct physiological changes and observable signs. Recognizing these stages allows EMRs to determine the urgency of the situation and prepare appropriately.

First Stage: Dilation

Begins with the onset of true labor contractions and ends with full cervical dilation (10 cm). It’s the longest stage, especially for first-time mothers.

What’s Happening Physiologically:

- Uterine muscles contract rhythmically to thin (efface) and open (dilate) the cervix.

- Cervical dilation progresses from 0 to 10 cm.

Defining Characteristics:

- Contractions start irregularly, then become more frequent (every 2–5 minutes) and intense.

- May last several hours to over 24 hours.

- “Water breaking” (rupture of membranes) may occur spontaneously or not at all.

- Patient may feel increasing pressure in the pelvis or lower back.

Key Considerations for EMRs:

- If contractions are more than 5 minutes apart and no crowning is observed, there may be time for hospital transport.

- Ask about past pregnancies—women with prior deliveries may progress faster.

Second Stage: Expulsion

Begins when the cervix is fully dilated and ends with the birth of the baby.

What’s Happening Physiologically:

- Strong contractions push the baby through the birth canal.

- The mother experiences an irresistible urge to push.

- The fetal head begins to crown (become visible at the vaginal opening).

Defining Characteristics:

- Contractions are intense and close together (2–3 minutes apart).

- Crowning occurs: the baby’s head remains visible during contractions.

- The mother may feel intense pressure or a “ring of fire” sensation.

Key Considerations for EMRs:

- Delivery is imminent if crowning is observed—do not attempt transport.

- Prepare for birth and reassure the mother.

- Stay calm and focused; most normal deliveries occur without complication.

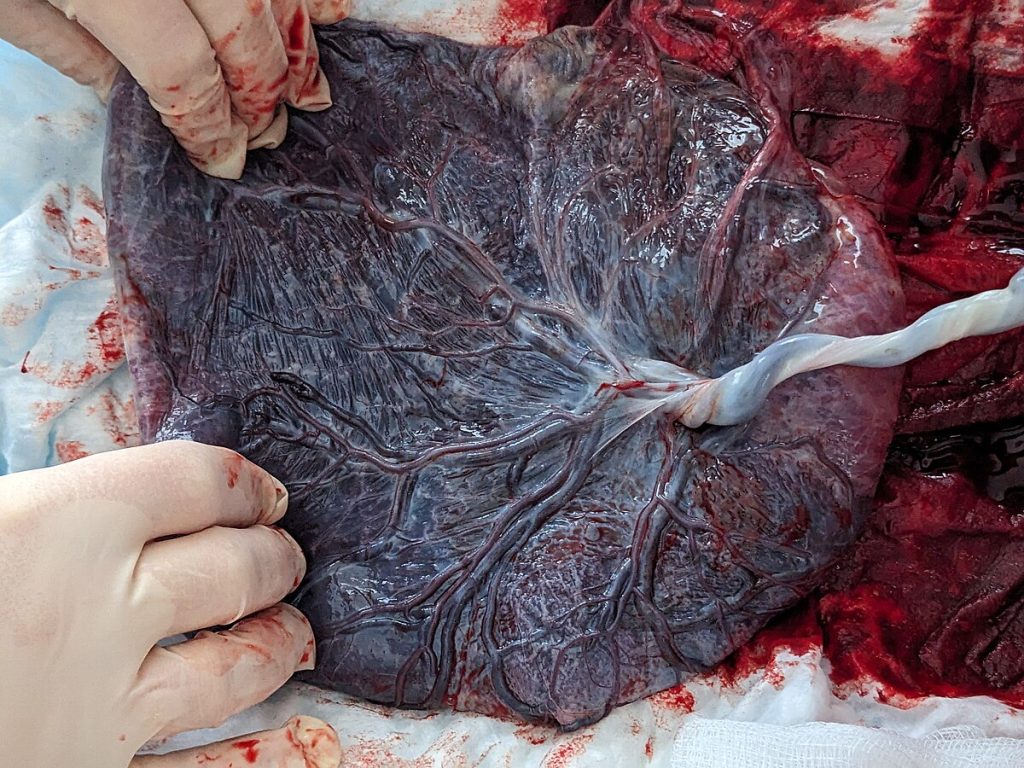

Third Stage: Placental Delivery

Begins after the birth of the baby and ends with the expulsion of the placenta.

What’s Happening Physiologically:

- Continued uterine contractions help detach and expel the placenta.

- The uterus begins to contract and return to pre-pregnancy size.

Defining Characteristics:

- Typically occurs within 5–30 minutes after delivery.

- Mild contractions resume.

- Some vaginal bleeding is expected, but excessive bleeding (>500 mL) may signal hemorrhage.

Key Considerations for EMRs:

- Never pull on the umbilical cord—this could cause uterine inversion or retained placenta.

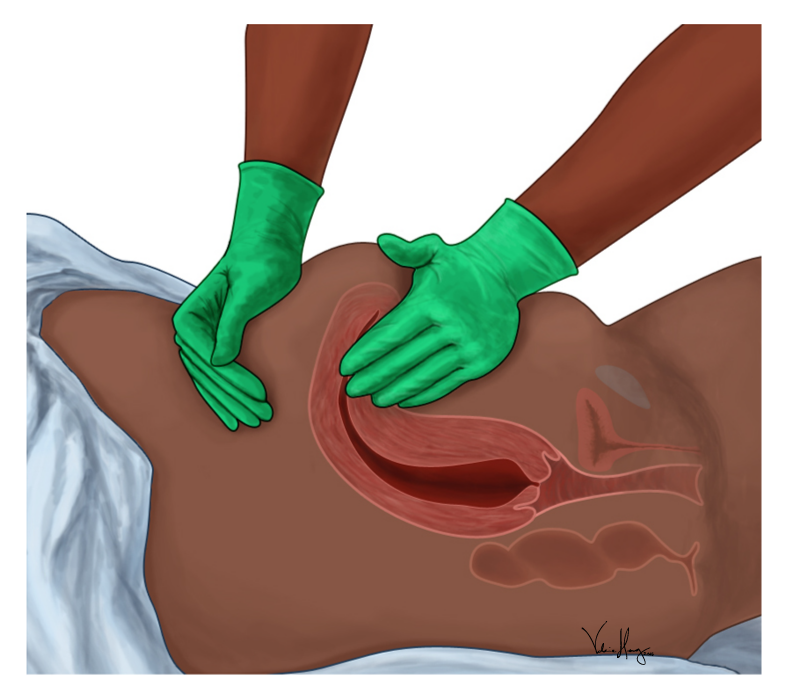

- Massage the fundus (top of the uterus) to encourage contraction and reduce bleeding.

- Save and transport the placenta for hospital evaluation.

Assessment and Approach to Normal Delivery

Estimating Gestational Age by Fundal Height

Determining gestational age helps guide delivery decisions and readiness for neonatal care.

Fundal Landmarks:

- 36–40 Weeks: Near the xiphoid process.

Helpful Questions:

- “How far along are you?”

- “Is this your first pregnancy?”

- “Have you had any prenatal care?”

- “Do you know of any complications with this pregnancy?”

- “Have your membranes ruptured (i.e., has your water broken)?”

- “Have you delivered before—and if so, how quickly?”

Signs of Imminent Delivery

These signs indicate that transport is not safe or feasible and delivery should occur on scene:

- Contractions < 2 minutes apart, lasting > 45 seconds.

- Strong urge to push or bear down.

- Crowning is visible.

- Patient says, “The baby is coming now.”

- History of precipitous (very fast) previous deliveries.

Preparing for Prehospital Delivery

Scene and Patient Preparation:

- Ensure privacy and scene safety.

- Position the patient lying supine with knees drawn up and legs apart, ideally on a clean surface.

- Don gloves, eye protection, and a gown if available.

- Use clean towels, sterile gauze, and OB kit if available.

Delivery Steps:

- Crowning Observed:

-

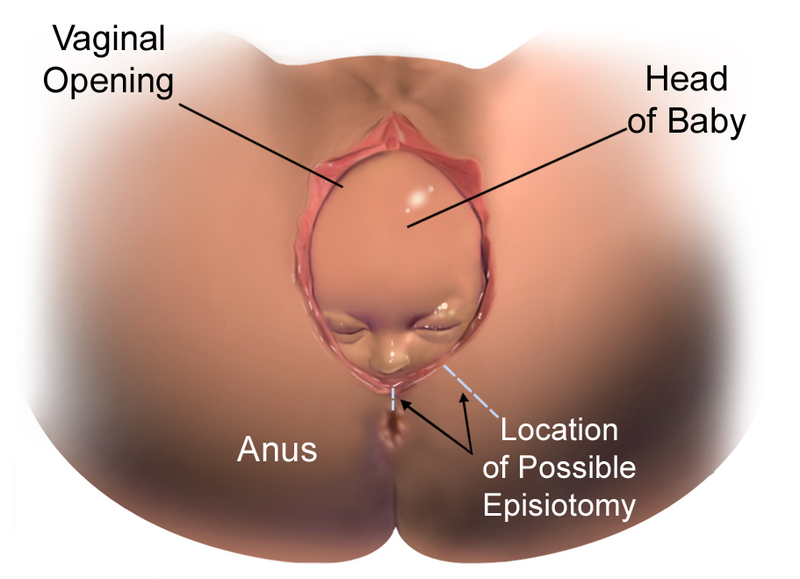

Figure 16.10 Do not try to stop delivery.

- Place the palm (not fingers) of your gloved hand gently on the baby’s head to control the speed of birth and avoid perineal tearing.

- If the amniotic sac (bag of waters) is still intact, you must puncture it with your fingers and allow the fluid to drain.

-

- Check for Nuchal Cord:

- Present in approximately one-third of full term infants.

- If the cord is wrapped around the neck, gently lift it over the head.

- If it is tight and cannot be slipped over, clamp and cut it quickly.

- Guide the Shoulders:

- Gently support the head as it rotates.

- Allow upper shoulder to deliver (guide downward), then lower shoulder (guide upward).

- Support and Deliver Baby:

Figure 16.11 - The baby will be slippery—support the head and body.

- Immediately dry and stimulate the baby.

- Have another dry towel or blanket to wrap the baby.

- Clear the Airway:

- Suction mouth then nose with a bulb syringe only if secretions obstruct breathing.

- Stimulate breathing by rubbing the back or soles of the feet.

View the following supplementary YouTube video to learn more about nuchal cords:

Nuchal cords during pregnancy and childbirth and complications

Cutting the Umbilical Cord

Procedure:

- Wait 30–60 seconds (or until pulsations stop).

- Clamp 6 inches and 8 inches from the baby.

- Cut between the clamps using sterile scissors or blade.

Delivery of the Placenta

- Do not pull on the cord.

- Placenta usually delivers within 30 minutes.

- Collect it in a plastic bag for transport.

- Massage the fundus (top) of the uterus with firm, circular motions after delivery to promote contraction and reduce bleeding. This is uncomfortable for the mother.

Reassessment After Delivery

Mother:

- Monitor vital signs and mental status.

- Observe vaginal bleeding—apply sanitary pads to assess volume.

- Treat for shock if pale, tachycardic, or hypotensive.

Newborn:

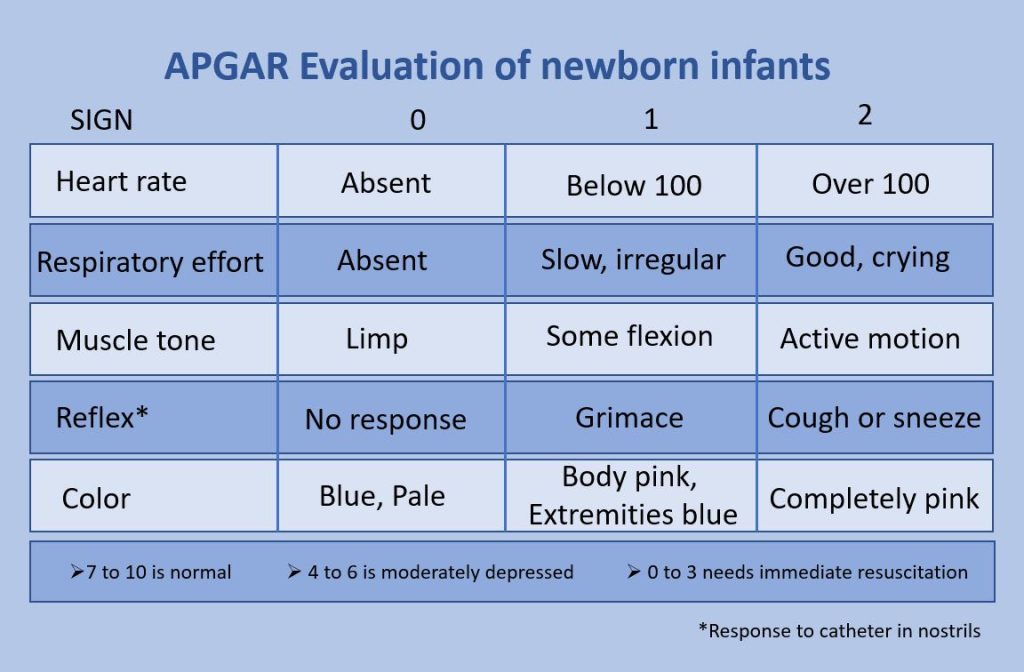

- Perform APGAR assessment at 1 and 5 minutes:

- Appearance, Pulse, Grimace, Activity, Respirations.

- Keep warm and dry—hypothermia is a serious neonatal risk.

- If possible, place the infant on the mother’s chest for skin-to-skin contact initially.

- Reassess every 5 minutes.

Practical Tips for the EMR

- Stay Calm and Reassuring—the mother takes emotional cues from you.

- Do Not Delay Delivery once crowning is evident.

- Support the Family—communicate clearly with family members or support people.

- Document Everything—contraction timing, times of crowning, birth, placenta delivery, interventions, and estimated blood loss (report number of pads or towels used).

View the following supplementary YouTube video to learn more about the delivery steps and considerations:

16.5 Abnormal Labor and Delivery

While most pregnancies progress without incident, some deliveries present unique and serious challenges that require quick thinking and precise action. Abnormal labor and delivery events can endanger both the mother and the fetus and demand that EMRs act decisively, often before advanced help arrives.

This chapter will guide you through the pathophysiology, assessment, and prehospital management of abnormal presentations and labor-related complications, building confidence for real-world scenarios where time and calm judgment are crucial.

Abnormal Deliveries: Pathophysiology, Assessment, and Care

Prolapsed Umbilical Cord

Pathophysiology: In a prolapsed cord, the umbilical cord precedes the presenting part of the fetus during delivery. The descending fetus may compress the cord between itself and the bony pelvis, leading to decreased or absent oxygen and nutrient delivery. This condition typically occurs after membrane rupture and is more common in transverse lies, breech presentations, or preterm deliveries.

Recognition:

- Visible or palpable cord in the vaginal canal.

- Sudden fetal bradycardia or distress (if auscultated or monitored).

- Patient may report feeling a “something slipping out” after water breaks.

EMR Care:

- Place mother in knee-chest or Trendelenburg position to relieve pressure on the cord using gravity.

- With sterile gloved fingers, gently elevate the presenting part off the cord.

- Do not manipulate or attempt to replace the cord.

- Cover any exposed cord with sterile, saline-soaked gauze to keep it moist.

- Provide high-flow oxygen to improve maternal oxygenation.

- Urgent ALS intercept and immediate transport. Notify the hospital early.

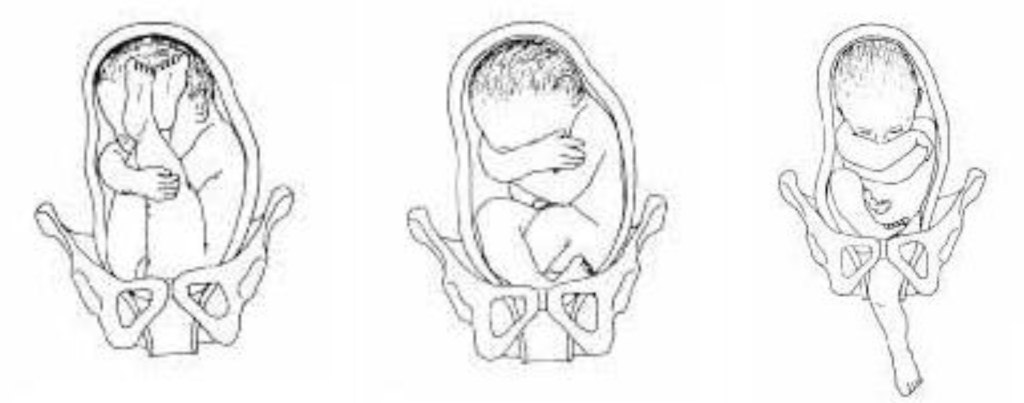

Breech Birth

Pathophysiology: A breech birth occurs when the fetus presents buttocks- or feet-first. This position is more likely before 37 weeks but may persist to term. The greatest danger lies in the possibility that the head—being the largest and least compressible part—becomes trapped, delaying expulsion and risking asphyxia.

Assessment:

- Visible buttocks or feet as presenting part.

- Slower delivery progress; limb flailing or umbilical cord visible before head.

- Mother may feel intense rectal pressure.

EMR Management:

- Allow spontaneous delivery up to the umbilicus without pulling.

- Support the baby’s body; if the head delays, insert two gloved fingers in a “V” to create an airway for the baby’s mouth and nose away from the vaginal wall.

- Do not pull on the baby’s legs or torso.

- Immediate transport if head is not delivered within 3 minutes of the torso.

- Anticipate neonatal resuscitation.

Shoulder Dystocia

Pathophysiology: This occurs when the anterior fetal shoulder becomes impacted behind the pubic symphysis after the head has delivered. It causes mechanical obstruction and umbilical cord compression, creating a true obstetric emergency. It is associated with fetal macrosomia (large baby), maternal diabetes, or prolonged second-stage labor.

Signs:

- Head delivers and then retracts (“turtle sign”).

- No further descent after pushing efforts.

EMR Actions:

- Do NOT pull on the baby’s head.

- Apply the McRoberts Maneuver: have the mother hyperflex her hips to widen the pelvis.

- Apply suprapubic pressure (not on the fundus) to dislodge the shoulder.

- If not resolved in 2–4 minutes, initiate emergency transport with ongoing care.

- Be prepared for neonatal hypoxia or trauma.

Figure 16.17

Precipitous Delivery

Pathophysiology: Delivery occurring within less than 3 hours of the onset of contractions. Caused by forceful, frequent uterine contractions and/or lack of cervical resistance. Risk of maternal tearing and neonatal trauma is increased.

Recognition:

- Sudden onset of intense, frequent contractions.

- Little time between contraction and crowning.

- Patient may express panic, urge to push, or report rapid descent.

EMR Care:

- Stay calm and prepare quickly for delivery on scene.

- Protect the perineum and support the baby as it emerges rapidly.

- Maintain newborn warmth (dry, wrap, skin-to-skin).

- Watch for postpartum hemorrhage and maternal tearing.

- Deliver placenta only if it presents spontaneously.

Multiple Births

Pathophysiology: More than one fetus is delivered. Twins or more pose higher risks of preterm labor, uterine atony, breech presentation, and hemorrhage. Each infant may require individualized care.

Recognition:

- Large fundal height for gestational age.

- Continued labor/contractions after first delivery.

- Presence of multiple fetal parts or sacs.

EMR Considerations:

- Prepare for multiple neonatal resuscitations.

- Label babies (Baby A, B, etc.) and note times of delivery.

- Clamp and cut umbilical cord as the infant is delivered.

- Anticipate postpartum hemorrhage due to uterine fatigue.

Preterm Labor and Birth

Pathophysiology: Labor occurring before 37 weeks gestation, often due to infection, uterine abnormalities, or trauma. Preterm babies have immature lungs, fragile blood vessels, and low fat stores.

Signs:

- Early, regular contractions.

- Membrane rupture.

- Small, underdeveloped infant (<5 lbs).

EMR Actions:

- Keep baby warm with plastic wrap or foil, hat, and warm blankets.

- Gentle handling to avoid trauma.

- If breathing is inadequate, use BVM with caution (risk of barotrauma).

- Expedite transport to a NICU-capable hospital.

Post-Term Pregnancy

Pathophysiology: Pregnancy lasting beyond 42 weeks. Risks include placental insufficiency, fetal macrosomia, meconium aspiration, and stillbirth.

Assessment:

- Lack of fetal movement.

- Mother reports overdue status.

- Meconium-stained fluid may be present at ROM.

EMR Interventions:

- Prepare for complications including birth trauma or non-vigorous neonate.

- Perform aggressive neonatal suctioning if meconium is present and the baby is not crying.

- Monitor for signs of postpartum hemorrhage.

View the following supplementary YouTube videos to learn more about the abnormal deliveries and considerations:

Complications of Labor and Delivery

Meconium-Stained Amniotic Fluid

Pathophysiology: A sign of fetal stress, especially in post-term or prolonged labor. If aspirated, it can cause chemical pneumonitis, airway obstruction, and respiratory distress.

Recognition:

- Yellow-green or brown fluid at ROM.

- Limp or unresponsive baby with no cry.

EMR Response:

- Suction mouth before nose with bulb syringe.

- If baby is not crying or breathing, initiate BVM ventilation.

- Anticipate need for advanced airway.

- Transport rapidly to facility with neonatal care.

Postpartum Hemorrhage (PPH)

Pathophysiology: Loss of >500 mL of blood within 24 hours postpartum. Often due to uterine atony, retained placenta, or lacerations.

Signs:

- Profuse vaginal bleeding.

- Soft, non-contracted uterus.

- Signs of hypovolemic shock: pale skin, tachycardia, hypotension.

EMR Management:

- Fundal massage to stimulate contraction.

- Allow baby to nurse if mother consents.

- Monitor bleeding closely; soak count of pads or towels is useful.

- Do not place any packing into the vagina.

- Administer high-flow oxygen.

- Position supine and keep warm.

- Transport urgently.

Amniotic Fluid or Pulmonary Embolism

Pathophysiology: Amniotic fluid or a blood clot enters maternal bloodstream during or shortly after labor, causing a massive inflammatory response or vascular obstruction, leading to sudden collapse.

Signs:

- Sudden onset of chest pain or dyspnea.

- Cyanosis, restlessness, or seizures.

- Cardiopulmonary arrest may follow rapidly.

EMR Actions:

- Immediate BLS and ALS support.

- Begin CPR if indicated.

- Provide high-flow oxygen, monitor vitals.

- Rapid ALS intercept and notification to ED.

16.6 Care of the Newborn

The transition from intrauterine to extrauterine life is a dramatic and delicate process. At birth, the newborn must suddenly begin breathing air, regulating body temperature, and functioning independently from the mother’s circulatory and respiratory systems. For most infants, this transition is smooth. However, approximately 10% of newborns require some level of assistance, and about 1% need advanced resuscitation efforts. EMRs must be prepared to act quickly and confidently during these critical moments to support the newborn’s adaptation to life outside the womb.

This chapter presents an assessment-based approach to newborn care in the prehospital setting, providing the knowledge and skills necessary for EMRs to evaluate and intervene during the first minutes of life. It includes the APGAR scoring system, oxygenation guidelines based on the Neonatal Resuscitation Pyramid, and resuscitation care aligned with American Heart Association and national standards.

Assessment-Based Approach to Newborn Care

The Initial Moments After Birth

From the moment a baby is born, the clock begins ticking. The first 30 seconds are crucial. EMRs must act swiftly and systematically to assess the newborn’s condition. The assessment begins even before the baby is fully delivered. Observations about amniotic fluid color, meconium staining, gestational age, and fetal tone can provide early warning signs of distress.

Once the infant is delivered, focus on three key questions:

- Is the baby full-term?

- Is the baby crying or breathing?

- Does the baby have good muscle tone?

If the answer to all three is yes, routine care may proceed. If the answer to any is no, begin with initial interventions to support breathing and circulation.

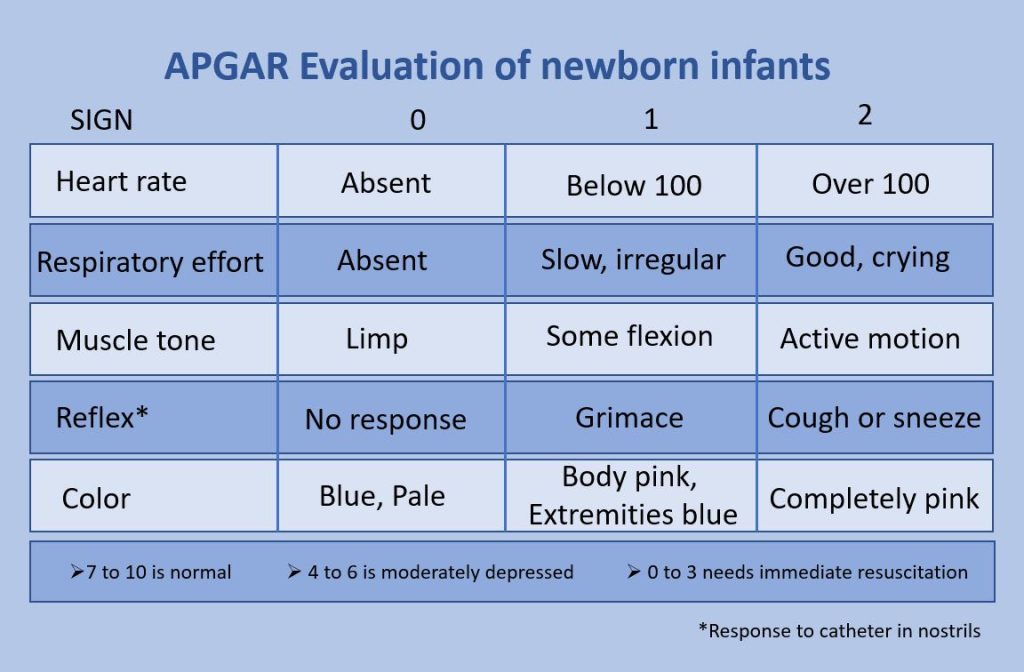

APGAR Scoring: A Framework for Field Assessment

The APGAR score provides a standardized way to assess the newborn’s clinical status and response to resuscitation. It is calculated at 1 minute and 5 minutes after birth. Each of five parameters is scored from 0 to 2, with a maximum score of 10.

A – Appearance (color)

P – Pulse (heart rate)

G – Grimace (reflex irritability)

A – Activity (muscle tone)

R – Respirations

Scoring Guidelines:

- 7–10: No resuscitation needed beyond routine care.

- 4–6: Moderate depression—may require stimulation and oxygen.

- 0–3: Severely depressed—immediate resuscitation required.

APGAR scoring is not used to direct resuscitation efforts but provides a structured framework to monitor progression and document the newborn’s status.

Emergency Medical Care: Interventions Based on Assessment

The Inverted Pyramid of Neonatal Resuscitation

The Neonatal Resuscitation Pyramid is a decision-making tool that organizes resuscitative actions in a sequence based on the infant’s response. It emphasizes starting with the least invasive steps and progressing only as necessary. The majority of newborns will respond to initial measures alone.

Initial Interventions: The First 30 Seconds

These actions should be initiated within the first 30 seconds after birth:

1. Vigorous Warming

Newborns are highly susceptible to heat loss, which can lead to hypothermia, hypoglycemia, and respiratory distress. Prompt drying with warm towels, placing the newborn under a radiant warmer, or skin-to-skin contact with the mother helps maintain body temperature.

- Remove wet towels and wrap the baby in a dry, warm blanket.

- Cover the head to minimize heat loss.

2. Appropriate Positioning

Position the newborn supine with the head in a neutral or slightly sniffing position to open the airway. A towel roll under the shoulders may help achieve this position.

3. Suction (Only If Needed)

Routine suctioning is no longer recommended. However, if the newborn is not breathing or has obvious airway obstruction:

- Suction the mouth first, then the nose.

- Use a bulb syringe or soft catheter.

- Avoid deep suctioning which may cause bradycardia or trauma.

4. Tactile Stimulation

If breathing is absent or irregular, stimulate the newborn:

- Gently rub the back or flick the soles of the feet.

- Avoid aggressive stimulation.

Secondary Interventions: Based on Clinical Response

If the newborn remains apneic, gasping, or has a heart rate below 100 bpm after initial interventions:

Positive Pressure Ventilation (PPV)

Effective ventilation is the cornerstone of neonatal resuscitation.

- Use a bag-valve-mask device with a neonatal mask.

- Deliver breaths at a rate of 40–60 breaths per minute.

- Watch for chest rise to confirm effective ventilation.

- Reassess heart rate and respirations after 30 seconds.

If chest rise is not observed:

- Reposition the head.

- Check the mask seal.

- Suction the airway again if needed.

Supplemental Oxygen

Oxygen should be titrated based on the newborn’s color and pulse oximetry. For term newborns, begin with room air unless signs of persistent cyanosis or low oxygen saturation exist.

- Use blow-by oxygen near the mouth and nose.

- Target SpO₂ values increase gradually after birth.

- Recognize newborns are normally ~60–65% at 1 minute.

- Then up to ~85–95% by 10 minutes.

Advanced Resuscitation: If Heart Rate <60 bpm After Ventilation

Chest Compressions

If the heart rate remains below 60 bpm after 30 seconds of effective ventilation:

- Begin chest compressions using the two-thumb encircling technique.

- Place thumbs just below the nipple line.

- Compress to a depth of one-third the chest diameter.

ALS Providers

- Coordinate higher level care and continue resuscitation.

Summary

Newborn care in the prehospital setting is one of the most time-sensitive and potentially life-saving responsibilities of the EMR. By performing a focused assessment, using APGAR scores, and following the Neonatal Resuscitation Pyramid, EMRs can identify distress early and take the right steps to support the newborn’s transition to life outside the womb. Mastery of these skills ensures better outcomes and reinforces the vital role of the EMR in early life-saving intervention.

16.7 Patients with Special Healthcare Needs

Introduction

As an EMR, you will encounter patients who present with a wide range of chronic illnesses, disabilities, and specialized health needs that fall outside typical emergency scenarios. These individuals may have physical, sensory, cognitive, or emotional impairments, or they may be socially vulnerable or medically dependent on home-based technology. Understanding how to adapt your assessment and interventions with these patients is not only essential for providing effective care but is also a reflection of your professionalism, compassion, and competence.

Caring for special medical needs begins with recognition. These patients often rely on unique supports—be it a caregiver, a home ventilator, or a coping mechanism for communication—and any disruption can turn an emergency into a moment of personal crisis. It is your role to stabilize not only their medical condition but also their trust, safety, and dignity in that moment.

While some patients have unique situations and considerations, always approach the scene with the same thoughts of safety and identify the need for additional resources. Perform your assessment and identify life- or limb-threatening issues. Rely on family or caregivers to provide a background and define what is different that prompted the emergency call. Take direction from these people who are typically well trained to interact with and care for these patients. Also identify specialty equipment that should accompany the patient to the hospital.

Patients with Sensory Impairments

Sensory impairments affect how individuals receive and process information about their environment. These can include impairments in hearing, vision, speech, or touch, each presenting unique challenges during emergency care.

A patient who is deaf or hard of hearing may not respond to questions or instructions. Some communicate using American Sign Language (ASL) or may read lips. In high-stress environments, however, even those who usually manage well may find communication difficult. EMRs should approach from within the patient’s line of sight and use simple, visible gestures. Writing notes or using text on a phone can facilitate interaction. Avoid shouting, which can seem aggressive.

Visual impairments can arise from various causes. The extent of visual impairment varies widely, ranging from partial vision loss to total blindness. Patients with vision impairments rely heavily on their remaining senses, particularly hearing and touch. Sudden or unexplained physical contact can be distressing. Verbally narrating your actions, identifying yourself clearly, and maintaining calm, clear communication fosters cooperation and reduces anxiety. Guide dogs or white canes should remain close to the patient whenever possible.

Speech impairments, often resulting from strokes or neurological conditions, require patience and creativity. These patients may understand you fully but be unable to respond clearly. Give them time, avoid interrupting, and ask simple yes/no questions when needed. Be sensitive to their frustration. Watch for non-verbal cues, such as facial expressions or gestures, especially to indicate pain.

Some individuals experience sensory processing disorders, especially those with autism. Bright lights, loud noises, or even the texture of medical gloves can provoke severe distress. In these cases, work with caregivers to understand how to reduce stimuli. If the environment allows, turn off sirens, reduce lighting, and avoid unnecessary touch.

EMR Tips for Sensory Impairments:

- Approach calmly and within the patient’s line of sight.

- Use clear, simple language and visual or written aids.

- Avoid assumptions—impairment does not imply cognitive deficit.

- Narrate your actions to vision-impaired patients.

- Reduce sensory stimulation for patients with sensory processing disorders.

Patients with Cognitive and Emotional Disabilities

Cognitive and emotional disabilities encompass a wide range of conditions that affect a person’s ability to understand, communicate, or respond to their environment. Patients may have congenital conditions such as Down syndrome or acquired disorders such as traumatic brain injury. Others may live with mental health challenges like severe anxiety, depression, schizophrenia, or PTSD.

Patients with intellectual disabilities might struggle with decision-making, attention, or communication. As an EMR, it’s critical to speak in short, direct sentences, allow additional time for responses, and involve caregivers when appropriate. Use visual cues or demonstrate tasks when possible. Patients may feel overwhelmed if multiple responders speak at once, so designate one person to communicate.

Autistic individuals often require structured environments and may have specific communication preferences. Some are non-verbal but capable of understanding language. Be aware that they may avoid eye contact, have repetitive behaviors, or become agitated by touch or loud noises. Allow them extra time and space, and respect their need for routine.

Mental and emotional disorders can affect mood, perception, and behavior. A patient experiencing paranoia or hallucinations may interpret your actions as threatening. Simply being a stranger in a uniform may be frightening to them. Always explain what you’re doing, avoid sudden movements, and keep your tone neutral. Demonstrating your next exam step or piece of equipment on yourself or their caregiver may show them it is not painful or dangerous. If a patient becomes agitated, back off, offer choices, and involve behavioral health support if available.

Patients with Down syndrome have additional medical considerations for emergency personnel. Hearing and vision impairments are common. Instability of the C1-C2 vertebrae occurs in about 15% of individuals, increasing the risk of spinal cord injury. Approximately 40% of individuals have congenital structural heart problems. Small oral cavities with larger tongues can make airway management challenging.

EMR Tips for Cognitive/Emotional Disabilities:

- Speak clearly and use short, simple sentences.

- Limit the number of people interacting with the patient.

- Allow time for the patient to respond.

- Avoid touching the patient unless necessary and explained.

- Recognize and de-escalate fear, anxiety, or agitation.

Patients with Central Nervous System Injuries

Patients with central nervous system (CNS) injuries may have mobility limitations, communication barriers, or altered levels of consciousness. These injuries could stem from spinal cord trauma, stroke, multiple sclerosis, or traumatic brain injury.

Patients with spinal cord injuries may be paralyzed below a certain point and require special equipment such as catheters or mobility aids. They might also be at risk for autonomic dysreflexia—a life-threatening condition marked by severe hypertension and headache, often caused by minor irritants like a full bladder or pressure ulcer. While neurologic injury is usually associated with loss of sensation, some patients may have hyperesthesia, or an increased sensitivity resulting in pain.

Traumatic brain injury (TBI) survivors may appear confused, disoriented, or emotionally labile. Ask about the patient’s baseline mental status to help determine if symptoms are new or expected. Always reassess frequently, as deterioration can be subtle. Approach slowly, speak clearly, and monitor for signs of rising intracranial pressure, such as changes in consciousness or vomiting.

Transporting CNS-injured patients requires care to avoid further damage. Protect any areas with reduced sensation and ask caregivers for insight on mobility techniques.

EMR Tips for CNS Injury Patients:

- Ask caregivers about the patient’s baseline behavior and mobility.

- Monitor mental status closely for changes.

- Watch for signs of autonomic dysreflexia.

- Be gentle and deliberate when moving patients with reduced sensation.

Patients with Bariatric Needs

Bariatric patients—individuals with obesity that affects health and mobility—may experience unique medical and logistical challenges during emergencies. They often live with chronic conditions such as diabetes, hypertension, or obstructive sleep apnea. Respiratory distress may be more severe due to body mass placing pressure on the lungs, particularly when the patient is lying flat.

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ A bariatric patient is seated in a wheelchair](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/68/2025/04/aitubo-7-701x1024.jpg)

In addition to medical considerations, bariatric patients may experience anxiety or reluctance related to prior negative healthcare experiences. Sensitivity, dignity, and respect are essential. Use appropriate-sized equipment, such as larger blood pressure cuffs and bariatric stretchers. Anticipate the need for additional personnel when lifting or moving the patient to prevent injury to both patient and providers.

Ask the patient about their preferred method of movement or positioning. Many are experts in their own care. Positioning them upright or in a semi-Fowler’s position may significantly improve their breathing. Monitor for signs of hypoxia, and consider early oxygen support if needed.

If a bariatric patient has been confined to their residence for a prolonged period, extricating and transporting them may require multiple resources and extended time. A consideration for your community is to identify this potential and establish a plan before it becomes necessary.

EMR Tips for Bariatric Patients:

- Use bariatric-rated equipment when available.

- Request additional lifting support early.

- Position for comfort and airway support.

- Monitor closely for respiratory compromise.

- Treat all patients with dignity and compassion.

Neglected, Abused, and Vulnerable Patients

Some emergencies involve patients who are neglected, abused, or otherwise vulnerable. These may include children or adults with signs of poor hygiene, malnutrition, repeated injuries, or a fearful demeanor. You may also encounter homeless individuals, victims of domestic violence, or human trafficking survivors.

It is important to look beyond physical symptoms and consider the broader context. Repeated calls to the same location, suspicious explanations, or injuries inconsistent with the mechanism of injury can all be warning signs. Victims may appear unusually compliant or fearful, avoid speaking, or defer entirely to a controlling companion.

Vulnerable populations include:

- Child abuse

- Intimate partner violence

- Elder abuse

- Sexual assault

- Homeless/unhoused

- Human trafficking, which includes:

- Sex trafficking

- Labor trafficking

- Domestic servitude

- Forced child labor

- Child soldiers

- Organ trafficking

- Familial trafficking

Human trafficking is everywhere.

Altoona School Superintendent Charged with Sex Trafficking & Producing Child Pornography

Milwaukee human trafficking, sex assault case; real estate broker accused

Learn more about the survivor led initiatives to fight human trafficking: Rebecca Bender Initiative

Learn more about global initiatives to fight human trafficking: Our Rescue

Creating a safe, private environment is critical. Speak with the patient away from caregivers if possible. Document findings factually, and never confront suspected abusers on scene. Familiarize yourself with local mandatory reporting laws and procedures. When in doubt, consult medical control or your EMS supervisor.

EMR Tips for Vulnerable Patients:

- Create a private, safe environment for assessment.

- Document observations factually and clearly.

- Be alert for inconsistencies in stories or injuries.

- Report suspicions according to local protocol.

- Treat patients with empathy, patience, and respect.

Trauma-Informed Care: A Little Extra Knowledge can go a Long Way

Why EMRs Should Learn and Apply Trauma-Informed Care

EMRs are often the first professionals to interact with patients during frightening or emotionally intense moments. Many patients—especially those who are children, elderly, and survivors of abuse or violence—may have experienced prior trauma. Without realizing it, traditional medical assessments and interventions can unintentionally re-trigger these experiences.

Trauma-informed care (TIC) is a patient-centered approach that acknowledges the impact of trauma on health and behavior. It involves recognizing signs of trauma, avoiding re-traumatization, and supporting recovery through compassion, communication, and safety. When EMRs adopt trauma-informed practices, they foster trust, reduce fear and resistance, and improve both patient and provider outcomes.

Key Points for EMRs to Consider in Trauma-Informed Care

When treating a potentially traumatized or vulnerable patient, EMRs should:

- Ensure physical and emotional safety.

- Create a calm, respectful environment.

- Approach slowly and avoid sudden movements or loud voices.

- Minimize the number of responders crowding the patient.

- Establish trust and transparency.

- Identify yourself clearly and explain each step before performing any action.

- Be honest about what to expect and how long it may take.

- Offer choices and support patient control.

- Whenever possible, offer options (e.g., “Would you like to sit or lie down?”).

- Respect the patient’s autonomy and preferences.

- Use empathetic and nonjudgmental communication.

- Listen actively and validate the patient’s emotions without minimizing or challenging their reactions.

- Avoid blaming language or tones of authority that may feel threatening.

- Be aware of trauma triggers.

- Recognize that some actions (e.g., restraint, bright lights, certain medical procedures) may remind a patient of past trauma.

- Modify techniques when feasible (e.g., cover exposed areas quickly, explain painful procedures in advance).

- Recognize cultural and individual sensitivity.

- Be respectful of the patient’s cultural background, language needs, and religious beliefs.

- Avoid stereotypes or assumptions.

- Collaborate with the patient.

- Involve the patient in their care as much as possible.

- Ask for permission before touching or moving the patient.

- Practice self-awareness and emotional regulation.

- Stay calm and composed—even in tense or emotional situations.

- Understand how your own stress response can affect the patient.

- Advocate for continued support.

- When appropriate, notify hospital staff or social services if trauma-related needs are identified.

- Document signs of emotional distress or previous trauma for continuity of care.

Resources for Trauma-Informed EMS Care

- National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians (NAEMT):

- Psychological Trauma in EMS Patients (PTEP) course

- Emphasizes the role of EMS providers in identifying and responding to psychological trauma.

- Website: https://www.naemt.org

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA):

- TIP 57: Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services

- While not EMS-specific, this is the gold standard guide for trauma-informed care principles.

- Website: TIP 57: Trauma-Informed Care in Behavioral Health Services | SAMHSA Library

Conclusion

Trauma-informed care isn’t a specialty skill—it’s a mindset that enhances every patient interaction. For EMRs, applying these principles builds trust, supports recovery, and improves scene safety and patient satisfaction. With even small adjustments to language, tone, and approach, EMRs can provide care that heals both body and mind.

Patients with Terminal Illness

Patients who are terminally ill often receive palliative or hospice care aimed at managing symptoms rather than curing diseases. These individuals may experience shortness of breath, uncontrolled pain, or sudden deterioration. A sudden change may catch family, loved ones, or caregivers by surprise and result in calling 911. A care coordinator may have been subsequently called and a treatment plan enacted. Do not be surprised when this plan is focused on home care rather than transport.

Before beginning any aggressive intervention, determine if the patient has an advanced directive, Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) order, or Physician Orders for Life-Sustaining Treatment (POLST) form. If available and valid, follow the patient’s documented wishes. In the absence of such documentation, speak with family members or caregivers about the patient’s usual status and preferences.

In many cases, your role will be to provide comfort: repositioning the patient to ease breathing, administering oxygen if permitted, and offering calm, supportive presence. “Do Not Resuscitate” does not mean do not treat. Even in urgent circumstances, prioritize dignity and respect. Death is not a failure of care—how you support a dying patient and their loved ones can be as meaningful as any medical intervention.

EMR Tips for Terminally Ill Patients:

- Check for DNR or POLST forms and follow accordingly.

- Focus on symptom relief and patient comfort.

- Reassure family and explain what you are doing.

- Avoid invasive procedures unless required.

- Treat the situation with compassion and presence.

Patients Using Home Medical Equipment

The healthcare system in the United States continues to prioritize increasing value by improving quality and reducing relative costs. One way this is achieved is by decreasing the length of hospital stays. Meanwhile, advances in medicine and medical technology allow more people with chronic diseases or injuries to live at home or in non-hospital settings.

Many patients depend on home-based medical devices such as oxygen concentrators, CPAP or BiPAP machines, tracheostomy tubes, ventilators, feeding tubes, or urinary catheters. These devices support daily life but can become sources of emergency when they malfunction, become dislodged, or are improperly used.

When responding to such situations, observe carefully and ask questions. Patients and caregivers often know the equipment best. If oxygen isn’t flowing, check the tank valve and tubing. If a tracheostomy is blocked, suctioning may relieve distress. In case of ventilator alarms, prepare to provide manual ventilation if needed until advanced providers arrive.

For devices like feeding tubes, ostomy bags, or catheters, your focus should be on securing the equipment, preventing contamination, and monitoring for signs of infection or bleeding. Avoid manipulating central lines or IV pumps unless specifically trained. Always bring relevant devices or supplies with the patient during transport.

As an EMR in the community, you will likely become familiar with locations of home-based care and patients dependent on medical equipment. Be an advocate for emergency planning in case of power outages, severe weather, or other possible disasters. It is always better to plan for resources or evacuation before you actually need to utilize any.

Common Home Medical Equipment for Patients – Functions and Troubleshooting

| Equipment | Function | Common Troubleshooting Tips |

|---|---|---|

| Home Medical Oxygen | Provides supplemental oxygen to patients with chronic respiratory conditions (e.g., COPD, heart failure). |

|

| Tracheostomy Tubes | Maintains an open airway in patients with upper airway obstruction or long-term ventilation needs. |

|

| CPAP/BiPAP Devices | Provides continuous or bilevel airway pressure to keep airways open, mainly for sleep apnea or CHF. |

|

| Home Ventilators | Mechanically delivers breaths for patients with respiratory failure or paralysis. |

|

| Ports and Central Lines | Provides long-term intravenous access for medications, nutrition, or dialysis. |

|

| Ventricular Assist Devices (VADs) | Assists or replaces function of one or both ventricles in severe heart failure. |

|

| Feeding Tubes (e.g., G-tube, J-tube) | Delivers nutrition or medication directly into the stomach or intestine. |

|

| Ostomy Bags | Collects waste from a surgically diverted bowel or urinary tract. |

|

| Urinary Catheters (Foley or Suprapubic) | Drains urine for patients with bladder dysfunction. |

|

EMR Tips for Home Medical Equipment:

- Ask the patient or caregiver how the equipment normally functions.

- Check for obvious issues: disconnected tubing, power loss, alarms.

- Use manual interventions (e.g., BVM) if necessary.

- Transport the device and its supplies if possible.

- Do not attempt to fix or access devices beyond your training.

References:

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (2025). About Us. https://www.acog.org/about

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Pregnancy. https://www.cdc.gov/pregnancy

Division of Reproductive Health. (2025). About reproductive health. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth

Ho, A. L., Hernandez, A., Robb, J. M., Zeszutek, S., Luong, S., Okada, E., & Kumar, K. (2022). Spontaneous miscarriage management experience: A systematic review. Cureus, 14(4), e24269. https://doi.org/10.7759/cureus.24269

Kilpatrick, S. J. (Ed.). (2017). Guidelines for perinatal care. American Academy of Pediatrics; The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. https://hscsnhealthplan.org/sites/default/files/OB%20-%20ACOG%20Guidelines%20for%20Perinatal%20Care%20-%208th%20Edition.pdf

National Association of Emergency Medical Technicians (NAEMT). (2022). Pediatric education for prehospital professionals. Jones & Bartlett Learning.

National Highway Traffic Safety Administration. (2021). 2021 National Emergency Medical Services Education Standards [PDF]. https://cdn.ymaws.com/naemse.org/resource/resmgr/files/ems_education_standards_2021.pdf

Pollak, A. N., Mejia, A., McKenna, K., & Edgerly, D. (2021). Emergency care and transportation of the sick and injured (12th ed.). American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons (AAOS).

RAINN. (2025). About Rainn. https://rainn.org/about-rainn

Wisconsin Department of Health Services. (2025). Emergency medical services (EMS). https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/ems

Wisconsin Department of Health Services. (2025a). EMS: Scope of practice and protocols. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/ems/licensing/scope.htm

Images:

Figure 16.1: “Uterus_and_nearby_organs” by NIH Medical Arts is in the Public Domain.

Figure 16.2: “Menstrual-cycle-phases” by Elara Care is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 16.3: “2917_Size_of_Uterus_Throughout_Pregnancy-02” by English is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Figure 16.4: “4a25573a0e278f97388458baa77a0b25fc5c7e5f” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/10-3-common-discomforts-of-pregnancy

Figure 16.5: “Ectopic_Pregnancy” by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 16.6: “2906_Placenta_Previa-02” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Figure 16.7: “Blausen_0737_PlacentalAbruption” by Blausen.com staff (2014). “Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014 is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Figure 16.8: “6201e447a83e81d93ee4d66beb063558c62ce402” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/maternal-newborn-nursing/pages/11-3-care-in-the-second-trimester-of-pregnancy

Figure 16.9: “2920_Stages_of_Childbirth-en” by Jmarchn is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Figure 16.10: “Blausen_0294_Delivery_Crowning” by BruceBlaus is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Figure 16.11: “HumanNewborn” by Ernest F is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Figure 16.12: “Umbilicalcord.jpg” by Tristan Denyer is licensed under CC0

Figure 16.13: “Human_placenta_just_after_delivery” by Grendelkhan is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 16.14: “Side_View_of_Postpartum_Uterine_Massage_with_Internal_Anatomy” by Valerie Henry is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 16.15: “APGAR_score” by Dr.Vijaya chandar is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 16.16: “Pnalgas1“, “Pnalgas2“. and “Pnalgas3” by César AuMaVa~commonswiki is in the Public Domain.

Figure 16.17: “McRoberts_maneuver” by geraldbaeck is licensed under CC0, Public Domain

Figure 16.18: “Twin_breech” by C.Monck is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 16.19: “APGAR_score” by Dr.Vijaya chandar is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 16.20: Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/

Videos:

Shannon M. Clark, MD, MMS, FACOG. (2023, February 11). Nuchal cords during pregnancy and childbirth and complications [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=j6iXZXfzHXw&list=PLcQLs3xrRaYZZVsCovWpppAcjDgt7lTid&index=32

VVC EMT. (2022, February 3). VVC Emergency Childbirth [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=iUBw5fjfLh0

Limmer Education. (2022, September 13). Pregnancy & Delivery Emergencies in EMS [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lBYOVxS-3yg

Birth Injury Center. (2020, January 17). Umbilical Cord Prolapse [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ni621ZlVxUE

Birth Injury Center. (2020, February 5). Fetal Macrosomia (Overly Large Baby) [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://youtu.be/jSk_4LFjCiw?si=AoxnCfG1i27dQvgy