Chapter 12: Medicine Part 3

Jamie Howell, MSN, RN-EMT, CHSE

12.1 Introduction

Musculoskeletal disorders (MSDs) are conditions that affect the muscles, bones, joints, ligaments, and tendons. These disorders are not necessarily caused by trauma or injury but can result from chronic conditions, overuse, or systemic diseases. Examples of musculoskeletal disorders include arthritis, osteoporosis, and fibromyalgia. While these conditions may not always present as emergencies, EMS responders must be prepared to assist patients experiencing acute exacerbations, chronic pain, or complications related to these disorders.

This chapter explores common musculoskeletal disorders and provides guidelines for emergency responders to assess and care for patients with these conditions.

Learning Objectives

- Non-Traumatic Musculoskeletal Disorders 6.13

- Psychiatric or Behavioral Emergencies 6.7

- Respiratory 6.10

- Toxicology 6.9

12.2 Musculoskeletal Disorders and Emergency Medical Response

Understanding the Musculoskeletal System

The musculoskeletal system is a complex network that provides structure, movement, and protection for the body. Its key components include:

- Bones: Provide structural support and store minerals like calcium.

- Muscles: Enable movement and maintain posture.

- Tendons: Connect muscles to bones, allowing motion.

- Ligaments: Connect bones at joints, ensuring stability.

- Joints: Facilitate movement and bear weight.

When disorders affect any part of this system, they can lead to pain, stiffness, weakness, and limited mobility.

Common Musculoskeletal Disorders

Arthritis

- Description: Inflammation of the joints, causing pain, stiffness, and reduced range of motion. Common types include osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis.

- EMS Considerations: Patients may experience acute flare-ups, swelling, or difficulty moving. Chronic pain and deformities can also impact mobility.

Osteoporosis

- Description: A condition where bones become fragile and more prone to fractures due to loss of bone density.

- EMS Considerations: Patients with osteoporosis may experience spontaneous fractures, especially in the hips, spine, or wrists, without significant trauma.

Fibromyalgia

- Description: A chronic condition characterized by widespread musculoskeletal pain, fatigue, and tenderness in specific areas.

- EMS Considerations: Patients may report severe pain without an obvious cause, often accompanied by fatigue or cognitive difficulties (“fibro fog”).

Chronic Back Pain

- Description: Persistent pain in the lower or upper back, often due to degenerative disc disease or other spinal conditions.

- EMS Considerations: Back pain may limit the patient’s mobility, and improper handling can worsen their condition.

Emergency Care for Musculoskeletal Disorders (MSDs)

While most MSD-related emergencies are non-life-threatening, EMRs should focus on alleviating discomfort and preventing further complications.

Assessment

- Gather a thorough history, including the onset of symptoms and any pre-existing musculoskeletal conditions.

- Evaluate the affected area for swelling, deformities, and range of motion.

- Ask the patient to describe their pain using a pain scale (0-10).

- Check for signs of complications like nerve involvement (numbness or tingling) or circulatory compromise (pale or cold extremities).

Management

- Positioning: Help the patient find a comfortable position that reduces pain and pressure on the affected area.

- Immobilization: Use splints or other devices if necessary to stabilize the affected area and prevent further injury.

- Pain Management: While EMRs typically do not administer pain medication, you can provide reassurance and gentle support to minimize discomfort.

- Monitor for Complications: Observe for signs of worsening conditions, such as difficulty breathing (if ribs or spine are involved) or impaired circulation.

- Transport Considerations: Use caution during transport, especially with conditions like osteoporosis or chronic back pain, as sudden movements can exacerbate symptoms or cause fractures.

Key Takeaways

- Musculoskeletal disorders can significantly impact a patient’s quality of life and mobility, even in the absence of trauma.

- EMRs play a critical role in assessing and managing acute symptoms of MSDs while prioritizing patient comfort and safety.

- Understanding the unique needs of patients with conditions like arthritis, osteoporosis, or chronic pain ensures better outcomes and compassionate care.

12.3 Psychiatric and Behavioral Emergencies

Introduction

Behavioral emergencies arise when individuals exhibit abnormal behavior that is dangerous, disruptive, or distressing to themselves or others. These situations can result from mental health conditions, substance use, or extreme stress. EMRs are often the first to interact with such patients and must balance providing compassionate care with maintaining safety for everyone involved.

Behavioral Emergencies

Behavioral emergencies can present in many ways, including agitation, aggression, withdrawal, or confusion. Common causes include:

- Mental Health Conditions: Schizophrenia, bipolar disorder, or severe depression.

- Substance Use: Alcohol, illicit drugs, or medication interactions.

- Medical Conditions: Low blood sugar, brain injuries, infections, or oxygen deprivation.

- Stress and Trauma: Emotional or physical trauma can trigger panic, grief, or shock.

Assessment in Behavioral Emergencies

- Scene Safety

- Always ensure the scene is safe before approaching the patient. Be aware of potential weapons or hazards.

- Request law enforcement assistance if there is a threat of violence.

- Patient Observation

- Note the patient’s appearance, speech, and behavior. Look for signs like dilated pupils, sweating, or erratic movements.

- Gauge the patient’s level of consciousness and ability to communicate.

- Interviewing the Patient

- Approach calmly and avoid sudden movements. Maintain a non-threatening posture.

- Introduce yourself and explain your role.

- Ask open-ended questions like, “Can you tell me what’s going on?”

- Gathering Information

- Ask family, friends, or bystanders about the patient’s medical and behavioral history.

- Look for signs of substance use or medical conditions that could explain the behavior.

Managing Behavioral Emergencies

- De-escalation Techniques

- Speak in a calm, steady voice. Avoid arguing or raising your voice.

- Validate the patient’s feelings without judgment. For example, say, “I understand you’re upset, and I want to help.”

- Provide clear, simple instructions.

- Building Trust

- Use the patient’s name and maintain eye contact (if culturally appropriate).

- Be honest about what you’re doing and why.

- Avoid making promises you can’t keep.

- Physical and Emotional Safety

- Maintain a safe distance. Keep exits accessible and avoid cornering the patient.

- If restraint becomes necessary, follow local protocols and ensure the safety of everyone involved.

Common Psychiatric Conditions

- Anxiety and Panic Disorders

- Symptoms: Rapid breathing, sweating, dizziness, or chest pain.

- Care: Encourage slow, deep breathing. Reassure the patient that they are safe.

- Depression

- Symptoms: Fatigue, hopelessness, and potential suicidal thoughts.

- Care: Listen empathetically and ask directly about suicidal intentions. Do not leave the patient alone if they are at risk.

- Substance-Induced Behavioral Changes

- Symptoms: Aggression, hallucinations, or paranoia.

- Care: Monitor vital signs and avoid confrontation. Ensure the patient’s airway remains clear.

Psychiatric and Behavioral Disorders: Patients Who Are Violent to Others

Patients experiencing behavioral emergencies can become aggressive or violent due to a variety of factors, such as medical conditions, mental health issues, substance abuse, lack of oxygen, or head injuries.

Indicators of Potential Violence

- Physical Cues: Agitation, pacing, rapid or incoherent speech, shouting threats, clenching fists, or adopting a fighting stance.

- Object Use: Patients might throw objects or use them as weapons.

Safety Measures:

- Be alert to the patient’s posture and comments.

- Identify potential exit routes for your safety.

- Remove objects that can be used as weapons when safe to do so.

- Avoid approaching if the patient possesses a weapon.

Sexual Assault and Rape

Sexual assault and rape victims experience profound physical and emotional trauma. Providing sensitive and professional care is essential.

Initial Steps:

- Preservation of Evidence: Avoid cleaning or allowing the patient to clean themselves. Use a clean white sheet to collect debris or evidence during care.

- Respect and Reassurance: Clearly explain each action to the patient, ensuring they feel supported.

Stages of Rape-Trauma Syndrome:

- Acute Phase: Immediate need for critical emotional and physical support.

- Outward Adjustment Phase: Ongoing internal turmoil despite outward normalcy.

- Resolution Phase: Long-term healing requiring professional counseling.

Collaborate with Sexual Assault Nurse Examiners (SANE) when possible and follow legal protocols for evidence preservation.

Pediatric Considerations: Child Abuse and Neglect

Child abuse can manifest as physical, emotional, or sexual assault, often coupled with neglect. Identifiable patterns include:

- Physical Abuse: Unexplained injuries, burns, or bruises in various stages of healing.

- Neglect: Lack of supervision, malnutrition, unsafe environments, or untreated chronic illnesses.

Reporting:

- Mandatory reporting laws require suspicion of abuse to be reported to authorities. Reports made in good faith typically protect reporters from liability.

Considerations for Older Adults: Elder Abuse and Neglect

Elder abuse includes physical, sexual, or emotional mistreatment, as well as neglect by caregivers. Signs may include:

- Physical Abuse: Unexplained injuries, burns, or bruises.

- Neglect: Malnutrition, improper clothing, unsafe living conditions, or untreated medical issues.

Reporting:

- Familiarize yourself with state laws and report suspicions of abuse to appropriate authorities. Like child abuse reporting, good faith protects against liability.

Managing Behavioral Emergencies

Scene Safety:

- Assess the environment for risks to yourself, patients, or bystanders.

- Be aware of patient behaviors, including hallucinations or delusions, but do not validate false perceptions.

Building Rapport:

- Use calm, empathetic communication.

- Maintain a safe distance and gain permission before touching the patient.

- Show active listening to build trust and encourage cooperation.

Professional Support:

- Engage advanced personnel (EMS, law enforcement, or crisis centers) for situations involving suicidal patients, rape victims, or violent individuals.

Key Communication Tactics:

- Speak in a calm, reassuring voice.

- Use deliberate movements and avoid sudden actions.

- Rephrase patient responses to show understanding and encourage dialogue.

These measures ensure the safety and dignity of both responders and patients during behavioral emergencies.

To properly care for a patient exhibiting symptoms of a behavioral emergency, especially one who has been struggling with substance use and has recently experienced personal loss, consider the following steps and resources:

1. Patient Assessment:

- Observe Behavior: Monitor for signs of agitation, withdrawal, or aggression. Given the patient’s history, assess for any withdrawal symptoms related to substance use, depression, or a potential mental health crisis (e.g., anxiety, panic attacks, or suicidal ideation).

- Ask Relevant Questions: In addition to obtaining basic health information, inquire about the patient’s mental state, feelings of hopelessness, or any thoughts of harming themselves or others.

- Assess Physical and Mental Status: Consider any signs of overdose, head injuries, or physical trauma that may be contributing to the behavioral changes. Assess vital signs, oxygen levels, and glucose levels as changes in these could be linked to disorientation or violent behavior.

2. Calming Techniques:

- Establish Rapport: Use a calm, empathetic tone to build trust. Gently explain the situation to the patient, offering reassurance that you are there to help.

- Non-Threatening Approach: Keep a safe distance and avoid sudden or aggressive movements, which could escalate the situation. Allow the patient to express their feelings and concerns, but stay focused on their safety and yours.

3. Consider Mental Health and Substance Use:

- Substance-Use History: Given the patient’s admission of drug rehabilitation and recent lapse, consider the possibility of withdrawal symptoms or relapse. Withdrawal from substances such as alcohol or opioids can cause confusion, agitation, and aggression.

- Mental Health Issues: The recent loss of close relatives may trigger depression or exacerbated emotional distress, potentially leading to suicidal thoughts or manic behavior. Be alert to any signs of depression or an emotional crisis, including hopelessness or an inability to cope.

4. Safety First:

- Personal Safety: Always prioritize your safety and the safety of the patient and others on the scene. Identify any objects that could be used as weapons. If necessary, request assistance from law enforcement if the situation escalates.

- Monitor for Escalation: Observe for signs of escalating aggression (e.g., clenched fists, shouting, or a threatening posture). Be prepared to withdraw from the situation if it becomes unsafe.

5. Additional Resources:

- Law Enforcement: If the patient poses a risk to themselves or others, or if there is a history of violent behavior, law enforcement involvement may be necessary to safely manage the situation.

- Mental Health Professionals: Given the patient’s emotional distress and possible psychiatric condition, consider contacting mental health professionals or a crisis intervention team for expert evaluation and care.

- Substance Use Support: Since the patient has a history of substance abuse, it may be important to connect them with specialized addiction treatment services or a crisis stabilization unit that can address both their mental health and substance use concerns.

- Transport to Appropriate Facility: Depending on the patient’s condition, they may need to be transported to a psychiatric facility, emergency room, or detox center for further evaluation and treatment.

6. Documentation and Follow-Up:

- Thorough Documentation: Document all relevant observations, communications with the patient, and any interventions provided, including any restraints used (if applicable), and the reasons for their use.

- Family and Bystander Input: If possible, involve family members or close contacts to gain more context about the patient’s condition, including their medical history, recent emotional or physical changes, and any medication noncompliance.

7. Legal and Ethical Considerations:

- Legal Authorization for Restraints: If restraints are required, ensure that they are used in accordance with local laws and protocols, and only with authorization from law enforcement or advanced medical direction.

- Confidentiality: Maintain patient confidentiality while communicating with mental health professionals or law enforcement.

By following these steps and collaborating with appropriate resources, you can help manage the patient’s behavioral emergency in a way that prioritizes their safety, well-being, and dignity.

12.4 Respiratory Emergencies

Breathing is fundamental to life, and the ability to ensure that a patient can breathe effectively is essential for any EMR. The airway must remain open for oxygen to flow into the lungs and carbon dioxide to exit. Without an open airway, a person will not be able to breathe, and the lack of oxygen can quickly lead to death. When assessing a patient, always ensure their airway is open and unobstructed. A conscious patient who can speak or cry is likely breathing and has an open airway, but unconscious patients require immediate assessment for any obstructions.

Once the airway is secure, it’s important to assess the patient’s breathing. If the patient is experiencing difficulty breathing, artificial ventilation might be necessary to help them get the oxygen they need. Respiratory emergencies can manifest as either respiratory distress (when breathing becomes difficult) or respiratory arrest (when breathing stops altogether). This chapter will explore the causes, signs, and symptoms of respiratory emergencies, highlighting both chronic conditions like Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD) and acute emergencies such as asthma and pulmonary embolism.

The Respiratory System

Anatomy and Function

The respiratory system is divided into the upper and lower airways. The upper airway includes the nasal and oral cavities, where air enters the body. From there, air travels through the pharynx and passes through the larynx and trachea before reaching the lungs. The lower airway consists of the trachea, bronchi, bronchioles, and alveoli, where gas exchange occurs. The alveoli are tiny sacs in the lungs where oxygen is transferred into the bloodstream and carbon dioxide is removed.

Breathing is controlled by the brain, which monitors oxygen and carbon dioxide levels in the body. When there is an issue with the respiratory system, it can lead to insufficient oxygen delivery, which affects the entire body, especially vital organs like the brain. Inadequate breathing can be caused by a variety of conditions, including trauma, illness, or chronic diseases, and can quickly become life-threatening.

Respiratory Emergencies

A respiratory emergency occurs when the airflow into and out of the lungs is obstructed or compromised. This can lead to reduced oxygen levels in the bloodstream, which can stop the heart and prevent blood from circulating to vital organs. The brain, which requires a constant supply of oxygen, begins to deteriorate within minutes if deprived of oxygen. After 4-6 minutes, brain damage is possible; after 10 minutes, brain damage is certain. There are two types of respiratory emergencies: respiratory distress and respiratory arrest.

Types of Respiratory Emergencies

- Respiratory Distress

Respiratory distress refers to a condition in which breathing becomes difficult, but the patient is still able to breathe on their own. It can result from various causes, including:- Obstructions (e.g., choking)

- Asthma attacks

- Pneumonia

- Trauma to the chest or lungs

- Allergic reactions

- Chronic conditions like COPD

- Respiratory Arrest

Respiratory arrest occurs when the patient’s breathing completely stops. This is a life-threatening situation requiring immediate intervention, often with artificial ventilation or CPR.

Patient Example:

Lisa’s Asthma Attack: Lisa, a 27-year-old teacher, had always managed her asthma with medication and avoided triggers like pollen and pet dander. One evening, while outside gardening, she was exposed to dust and pollen, which triggered an asthma attack. Lisa began to cough uncontrollably, and her breathing became labored. She started wheezing and had difficulty speaking full sentences. Her skin turned pale, and she felt tightness in her chest. Fortunately, her inhaler was nearby, and she used it immediately, but her breathing continued to worsen, prompting a call for help. When EMS arrived, Lisa was showing signs of respiratory distress and was administered supplemental oxygen to aid in her breathing. She was later transported to the hospital, where her asthma was stabilized.

Causes of Respiratory Emergencies

Breathing problems can arise from various factors affecting the airway, the lungs, or the heart. Some common causes include:

- Obstructions

Choking, either from food or an object blocking the airway, is one of the most common causes of respiratory distress. For children, choking hazards are often small toys or food items, while for adults, an obstructed airway may result from alcohol consumption or unconsciousness. - Asthma

Asthma is a chronic condition where the airways become inflamed, narrowing the passage for air to move in and out of the lungs. Asthma attacks are often triggered by allergens, cold air, exercise, or stress. In an asthma attack, patients may experience wheezing, shortness of breath, and chest tightness. - Pneumonia

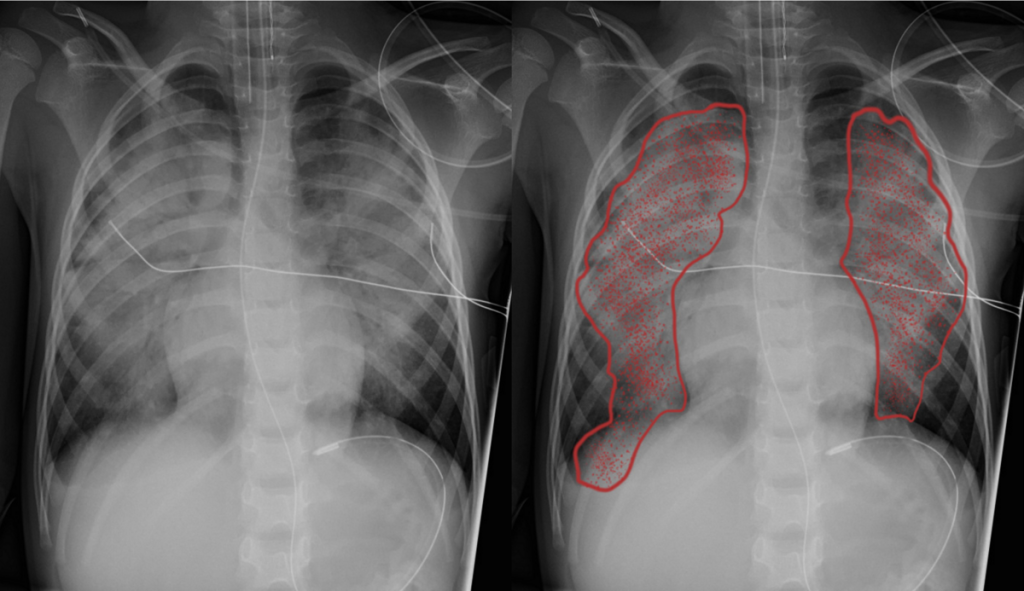

Pneumonia is an infection that causes the air sacs in the lungs to fill with fluid or pus. This impedes the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide and causes difficulty breathing. Symptoms include fever, chills, chest pain, and shortness of breath. - Pulmonary Embolism

A pulmonary embolism occurs when a blood clot blocks one of the pulmonary arteries, preventing blood flow to the lungs. The blockage impairs gas exchange, causing difficulty breathing and chest pain. A pulmonary embolism can be life-threatening and requires immediate treatment.

Patient Example:

Tom’s Pulmonary Embolism: Tom, a 60-year-old man, had been recovering from knee surgery and was largely confined to his bed. One afternoon, he suddenly experienced sharp chest pain and difficulty breathing. His breath became rapid and shallow, and he felt light-headed. He was rushed to the hospital, where doctors discovered a pulmonary embolism caused by a clot from his leg. Timely intervention saved his life, but the event underscored the importance of mobility and early intervention in patients at risk for blood clots.

Signs and Symptoms of Respiratory Emergencies

The signs and symptoms of a respiratory emergency can vary, but common indicators include:

- Slow or rapid breathing

- Shallow or deep breathing

- Gasping for air

- Wheezing or gurgling noises

- Cyanosis (bluish skin, especially around lips or fingers)

- Shortness of breath

- Dizziness or confusion

- Chest pain or tightness

- Pale or moist skin

Recognizing these signs is essential for identifying respiratory emergencies early and providing timely intervention.

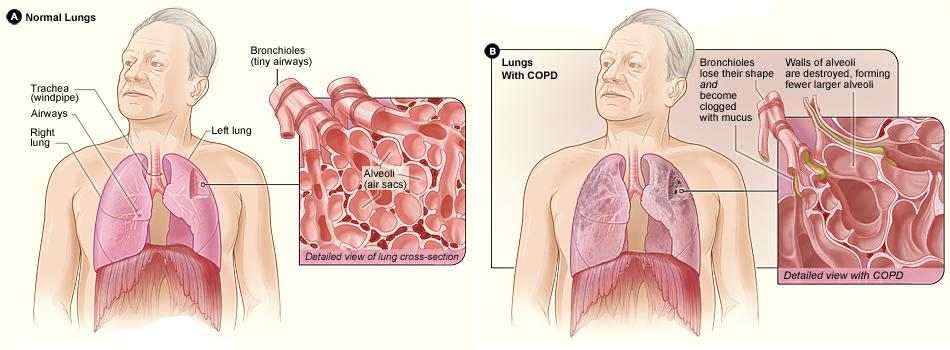

Chronic Obstructive Pulmonary Disease (COPD)

COPD is a progressive lung disease that causes difficulty in breathing due to damage to the lungs, often resulting from long-term smoking or exposure to pollutants. Symptoms include chronic cough, wheezing, fatigue, and shortness of breath. Patients with COPD may have a barrel-shaped chest and can become confused due to a lack of oxygen in the blood. COPD exacerbations may require immediate oxygen therapy and medication.

Acute Pulmonary Edema

Acute pulmonary edema is a life-threatening condition where fluid builds up in the lungs, impairing oxygen exchange. It is often caused by heart failure and can present with symptoms such as shortness of breath, wheezing, and coughing up pink, frothy sputum. Rapid intervention with oxygen and transport to the hospital is crucial for survival.

Hyperventilation

Hyperventilation occurs when a person breathes rapidly, reducing the carbon dioxide levels in the blood and causing dizziness and anxiety. It is often triggered by emotional stress or anxiety, but can also result from medical conditions like asthma or head trauma. Treatment involves helping the patient breathe slowly and calmly, using pursed lip breathing if necessary.

Conclusion

Recognizing the signs and symptoms of respiratory distress and arrest is critical for EMRs. Early intervention can make the difference between life and death. Whether caused by chronic conditions like asthma or COPD or acute events like choking or a pulmonary embolism, prompt and effective care is essential. Through patient assessment and timely treatment, EMRs can stabilize the patient’s condition and ensure they receive the necessary care.

By understanding respiratory emergencies and practicing the appropriate interventions, you can help save lives and ensure patients receive the oxygen they need to survive.

Pediatric Considerations in Respiratory Emergencies

It’s crucial to promptly identify and manage breathing emergencies in pediatric patients, as their hearts often stop due to respiratory issues, unlike adults whose cardiac arrest is more commonly linked to heart disease. Infants and children can experience respiratory distress due to various conditions, including birth defects, infections like bronchiolitis, pneumonia, or croup, as well as asthma or bronchospasms. Many respiratory conditions in children are preventable through vaccines, including those for diseases such as diphtheria, whooping cough, and pneumococcal infections. Though some illnesses may not manifest with respiratory symptoms, they can still spread through respiratory transmission, highlighting the importance of preventive care.

Considerations for Older Adults

Older adults may not always display the typical signs of respiratory distress, often because of diminished sensitivity to pain or other symptoms. Common respiratory issues in older adults include pneumonia, emphysema, and pulmonary edema, and their symptoms may differ from younger patients. It’s essential to observe their breathing patterns closely to detect any early signs of distress.

Opening the Airway

The head-tilt/chin-lift maneuver is the preferred method for opening the airway, except in cases where spinal injury is suspected. This technique lifts the tongue off the back of the throat, facilitating air entry. Alternatively, the jaw-thrust maneuver is used in cases where spinal injury is a concern, as it opens the airway without extending the neck.

Signs of an Open Airway

When the airway is open and clear, you’ll see the chest rise and fall with each breath. You may also hear air moving in and out of the patient’s nose and mouth. If the patient can speak in full sentences, it’s a sign that the airway is open and functioning normally.

Signs of an Inadequate Airway

Signs that the airway may be inadequate include visible difficulty breathing, gasping for air, or unusual sounds such as stridor (a high-pitched sound during inhalation) or snoring (often due to the tongue or soft tissues blocking the airway). A patient who is awake but unable to speak, or whose voice sounds hoarse, is experiencing significant respiratory difficulty. In the case of apnea (complete cessation of breathing), immediate intervention with artificial ventilation is necessary.

Causes of Airway Obstruction

There are two primary types of airway obstructions: mechanical and anatomical. Mechanical obstructions are caused by foreign objects (e.g., food, toy parts, or dentures), while anatomical obstructions occur when the tongue or other tissues block the airway, typically in unconscious patients. Conditions such as trauma, infections, or allergic reactions can also lead to swelling that obstructs the airway.

Clearing an Airway Obstruction

When a patient is conscious, airway obstructions can often be cleared with abdominal thrusts (Heimlich maneuver), back blows, or chest thrusts. The specific method used may vary based on the patient’s condition and the size of the obstruction.

In unconscious patients, techniques like finger sweeps or suctioning are employed to remove visible foreign matter. It’s important to use these methods carefully to avoid causing further injury to the airway.

Recovery Position

For unresponsive patients who are breathing normally, placing them in a side-lying recovery position can help keep the airway open and prevent choking. This is not recommended for patients with suspected spinal, head, neck, or pelvic injuries unless it’s necessary to maintain the airway or if you’re alone and need to call for help.

Assessing Breathing

To assess breathing, look for the rise and fall of the chest, listen for breath sounds, and feel for air escaping from the patient’s nose or mouth. Adequate breathing involves a normal rate, depth, and effort of breathing. For adults, this is typically 12-20 breaths per minute, with a slightly faster rate for children (15-30 breaths per minute) and infants (25-50 breaths per minute).

Signs of Inadequate Breathing

Signs of inadequate breathing include:

- Muscle retraction between the ribs, around the neck, and below the rib cage, indicating increased effort to breathe.

- Pursed-lip breathing, a technique used to regulate breathing.

- Nasal flaring in infants and children.

- Fatigue, anxiety, and sweating, all of which may indicate respiratory distress.

Other signs include paradoxical breathing, where part of the chest moves in the opposite direction during breathing, or abnormal breath sounds like stridor or wheezing. These signs often suggest that immediate intervention is needed to assist with ventilation.

Oxygenation and Ventilation

Oxygenation refers to the process by which oxygen enters the bloodstream, typically through the lungs, while ventilation is the physical movement of air in and out of the lungs. Adequate oxygenation results in normal mental status, skin color, and overall well-being.

Signs of inadequate oxygenation include cyanosis (a bluish discoloration of the skin or lips), mottling (blotchy skin caused by poor circulation), and signs of mental confusion or agitation.

Inadequate Oxygenation Causes

Causes of inadequate oxygenation may include poor air quality (such as in high altitudes or enclosed spaces), poisoning (e.g., carbon monoxide), or physical obstructions like lung injury. Without sufficient oxygen, the body can suffer severe complications, including brain damage and death.

Esophageal Opening Pressure and Complications in Ventilation

In normal ventilation, when the diaphragm contracts and moves downward, creating negative pressure in the chest, air enters the lungs. This process ensures that the esophagus remains closed, preventing air from entering the stomach. In contrast, during positive pressure ventilation, air is forcibly pushed into the lungs by the responder, typically using a device like a resuscitation mask or a BVM. This process, however, can increase the pressure in the chest, causing a decrease in venous return to the heart and reducing cardiac output.

One of the complications of positive pressure ventilation is that air can be pushed into the stomach due to the increased pressure in the abdomen. This can lead to gastric distention, which might cause vomiting and obstruct the airway. Additionally, air in the stomach can increase the risk of aspiration, making it critical for responders to avoid overventilation.

Overventilation and Hyperventilation

Overventilation refers to delivering too much air, either in volume or frequency, to the patient. This condition can have detrimental effects on the patient’s circulation, as it increases intrathoracic pressure. Elevated intrathoracic pressure decreases venous return to the heart and reduces coronary perfusion, leading to compromised circulation.

Hyperventilation, often caused by rapid or forceful ventilations, exacerbates this effect by further increasing the intrathoracic pressure, ultimately reducing the efficiency of blood flow to vital organs. To prevent these risks, responders should aim to deliver controlled, smooth breaths that cause the chest to rise without excessive force.

Assisted Ventilation During Respiratory Distress

Assisted ventilation is provided when a patient shows signs of inadequate breathing. This may occur due to respiratory distress or failure, where the patient’s body is not effectively oxygenating the blood. Symptoms indicating the need for assisted ventilation include:

- Breathing rates that are either too fast or too slow.

- Cyanosis (bluish color of the skin or mucous membranes).

- Insufficient chest wall movement.

- Changes in consciousness (restlessness, confusion).

- Chest pain or discomfort.

The procedure for assisted ventilation involves placing a resuscitation mask over the patient’s mouth and nose, ensuring a tight seal. The responder provides ventilation at the patient’s own breathing rate and gradually adjusts the ventilations as the patient’s breathing improves. Oxygen supplementation is provided as needed based on local protocols.

Special Considerations for Pediatric Patients

Both resuscitation masks and BVMs come in pediatric sizes. It is crucial to use the correct equipment for the patient’s size to ensure proper ventilation. Pediatric BVMs, for instance, are specifically designed for smaller airways, and using an adult-sized BVM can lead to ineffective ventilation or potential injury to the patient.

Ventilation Strategies for Specific Patient Conditions

- Stoma Patients: For patients with a stoma, use a pediatric resuscitation mask over the stoma to provide ventilation. Be sure to keep the patient’s head in a neutral position to avoid blocking the airway. If necessary, pinch the patient’s nose and close the mouth to ensure that air is delivered exclusively through the stoma.

- Head, Neck, or Spinal Injuries: If there is suspicion of a head, neck, or spinal injury, take special precautions when opening the airway. The jaw-thrust maneuver (without extending the neck) is preferred, as it minimizes the risk of exacerbating spinal injuries. Only use the head-tilt/chin-lift maneuver if the jaw-thrust does not adequately open the airway.

- Dentures: If the patient has dentures, they should generally be left in place as they help maintain a better seal during ventilation. However, if dentures are loose and obstructing the airway, remove them to ensure proper airflow.

By understanding these principles of ventilation and airway management, responders can help maximize oxygen delivery while minimizing complications during resuscitation efforts.

Substance abuse and misuse are serious public health concerns, extending beyond just illegal drugs to include widely available legal substances. While illegal drugs are often the focus of public discussion, legal substances like alcohol, tobacco, and prescription medications also play a significant role in the challenges of substance misuse. Misuse may involve using a substance for a purpose other than what it was intended for, or taking it in excess or without proper guidance, potentially leading to serious health issues.

The impact of substance abuse is extensive, with significant costs to healthcare systems, lost productivity, and lives lost due to overdoses and other complications. For example, drug overdose is now the leading cause of accidental death in the United States, surpassing even motor vehicle accidents. Beyond overdose, substance abuse contributes to a wide range of social and personal problems, including family breakdown, criminal behavior, and the spread of infectious diseases like HIV.

The consequences of long-term substance misuse are equally concerning. Many drugs, when used regularly, can lead to dependence, a condition where the person feels they need the drug to function normally. Addiction often follows, characterized by a compulsive need for the substance despite negative physical, emotional, or social consequences. Withdrawal symptoms can be severe, making it difficult for individuals to stop using the substance without medical help. This is especially true for substances like alcohol, which can cause life-threatening withdrawal symptoms.

Tolerance is another significant issue. As individuals continue to use a substance, their bodies often become accustomed to it, requiring them to increase the dosage to achieve the same effects. This can escalate the risk of overdose, especially when substances are used in combination, creating a potentially lethal synergistic effect.

Substance abuse and misuse span a wide variety of substances, including stimulants like methamphetamine and cocaine, hallucinogens like LSD and mushrooms, depressants like alcohol, and prescription medications, opioids, and cannabis. Each class of substance has its own effects on the central nervous system and body, and misuse can lead to a range of dangerous outcomes. For example, stimulants can increase heart rate and blood pressure, while depressants, including alcohol, can slow breathing and impair coordination, leading to accidents and overdose.

Ultimately, preventing and addressing substance abuse requires a multi-faceted approach. It involves educating the public about the risks of misuse, providing effective treatments for addiction, and ensuring that those struggling with dependency have access to the support and care they need to recover. Public health campaigns, legal regulations, and medical interventions all play essential roles in reducing the prevalence of substance misuse and its devastating consequences.

Opioid Narcotics: Case Scenarios

- Case Scenario 1: Opioid Overdose

- Patient: John, a 34-year-old male found unconscious in his apartment.

- Situation: John is unresponsive with slow, shallow breathing, and pinpoint pupils. Paraphernalia, including a syringe and a pill bottle with an expired prescription for oxycodone, are found nearby.

- Clinical Concern: Opioid overdose, with a risk of respiratory arrest.

- Care Plan: Administer naloxone via nasal atomizer and call for advanced medical personnel. Monitor vital signs and ensure airway patency. If John remains unresponsive, a second dose of naloxone may be required based on protocol.

- Case Scenario 2: Naloxone Administration Training

- Patient: Sarah, a 27-year-old female prescribed oxycodone for post-surgical pain management.

- Situation: Sarah’s family is concerned about her risk of opioid overdose. She has been educated about the risks and trained to administer naloxone in the event of an overdose.

- Clinical Concern: Educating patients on the proper use of naloxone and recognizing signs of opioid overdose.

- Care Plan: Provide hands-on training with naloxone nasal spray and auto-injector, ensuring Sarah understands when to administer the medication and how to seek help promptly.

Inhalants: Case Scenarios

- Case Scenario 1: Inhalant Abuse

- Patient: Mike, a 19-year-old male found disoriented and agitated in a public restroom.

- Situation: Mike is sweating profusely, has a strong odor of glue on his breath, and is displaying erratic behavior. Witnesses report he was inhaling from an aerosol can.

- Clinical Concern: Inhalant abuse with possible central nervous system depression and organ damage.

- Care Plan: Administer supplemental oxygen if available, call for advanced medical personnel, and monitor Mike’s vitals. Ensure airway is clear and provide reassurance.

- Case Scenario 2: Medical Consequences of Chronic Inhalant Use

- Patient: Brenda, a 56-year-old female with a history of chronic inhalant abuse.

- Situation: Brenda is exhibiting signs of heart and liver damage, with frequent chest pain and difficulty breathing.

- Clinical Concern: Long-term inhalant use resulting in damage to vital organs.

- Care Plan: Monitor Brenda’s respiratory and cardiac function, administer oxygen if needed, and transport her to a medical facility for further evaluation and management of organ damage.

Cannabis Products: Case Scenarios

- Case Scenario 1: Cannabis Intoxication

- Patient: Adam, a 22-year-old male, found in a public park with red, bloodshot eyes and impaired motor coordination.

- Situation: Adam reports smoking marijuana earlier that day. He exhibits symptoms of euphoria, altered perception, and a strong odor of cannabis.

- Clinical Concern: Acute cannabis intoxication, with impaired judgment and motor skills.

- Care Plan: Monitor Adam for any signs of further deterioration in vital signs. Reassure him and ensure safety until he returns to baseline. If necessary, call for advanced care if respiratory issues or complications arise.

- Case Scenario 2: Synthetic Marijuana Overdose

- Patient: Carla, a 19-year-old female found in a state of extreme agitation and hallucinations.

- Situation: Carla’s friends report she consumed synthetic marijuana (K2 or spice) earlier. She is pacing, yelling, and displaying erratic behavior.

- Clinical Concern: Synthetic marijuana overdose, with a risk of seizures, agitation, and possible life-threatening symptoms.

- Care Plan: Ensure Carla’s safety, provide reassurance, monitor vitals closely, and administer supplemental oxygen if she shows signs of respiratory distress. Call for advanced medical assistance as synthetic cannabinoids can have unpredictable and dangerous effects.

Designer Drugs: Case Scenarios

- Case Scenario 1: MDMA (Ecstasy) Overdose

- Patient: Lucas, a 25-year-old male, found in a concert crowd exhibiting rapid heartbeat, high blood pressure, and profuse sweating.

- Situation: Lucas is hyperactive and confused, complaining of nausea and dizziness. He admits to taking ecstasy (MDMA) at the event.

- Clinical Concern: MDMA overdose, with potential for dehydration, hyperthermia, and cardiovascular complications.

- Care Plan: Keep Lucas cool, administer fluids if appropriate, monitor heart rate and blood pressure, and call for advanced medical personnel to manage any life-threatening complications.

- Case Scenario 2: Hallucinogen-Induced Aggression

- Patient: Emily, a 28-year-old female, found in an alleyway exhibiting violent behavior and paranoia.

- Situation: Emily is unresponsive to verbal commands and seems to be hallucinating, claiming that people are following her. She admits to taking a designer drug, possibly LSD.

- Clinical Concern: Hallucinogen toxicity, with risk of self-harm or harm to others due to impaired judgment and perception.

- Care Plan: Ensure the scene is safe, monitor for self-harm, reassure Emily, and provide support until she calms down. Call for advanced care to assess her condition and manage any aggressive behaviors or psychiatric concerns.

These case scenarios help to contextualize how different substances impact patients in real-world situations, showing how responders can recognize symptoms, administer care, and make appropriate decisions to provide the best possible outcome.

References

American Red Cross. (2017). Emergency medical response.

Le Baudour, C., Wesley, K., & Bergeron, J. D. (2019). Emergency medical responder: First on scene (11th ed.). Pearson.

Le Baudour, C., Laurélle, K., Wesley, K., & Bergeron, J. D. (2024). Emergency medical responder: First on scene (12th ed.). Pearson.

Images:

Figure 12.1: ”Copd_2010Side” by National Heart Lung and Blood Institute is in the Public Domain

Figure 12.2: ”Comparison_PE” by Moustafa A. Mansour is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0