Chapter 10: Medicine Part 1

Jamie Howell, MSN, RN-EMT, CHSE

10.1 Introduction

(Needs to be written to be consistent with other chapters)

Learning Objectives

- Abdominal and Gastrointestinal Disorders 6.3

- Cardiovascular 6.8

- Disorders of the Eyes, Ears, Nose, and Throat 6.14

- Endocrine Disorders 6.6

10.2 Introduction to Medical Emergencies

As an EMR, you may encounter situations where the exact nature of a medical emergency is unclear. This uncertainty can be unsettling, but it’s important to remember that your role is to provide care to the best of your ability, not to definitively diagnose the patient’s condition. By relying on basic care principles and your training, you can confidently assist patients until more advanced medical personnel arrive.

Medical emergencies can vary widely in how they present. Some develop suddenly and require immediate attention, while others progress more gradually. Symptoms may be subtle or atypical, such as when older adults or individuals with diabetes experience a heart attack without the classic symptom of chest pain. Patients might only describe feeling generally unwell or sensing that something is wrong, which makes your assessment even more critical.

The causes of medical emergencies are diverse. They may stem from chronic illnesses like heart disease or diabetes, acute conditions such as allergic reactions or seizures, or environmental factors like extreme temperatures. Signs and symptoms can range from altered mental status and dizziness to nausea, vomiting, or changes in breathing and pulse. If a patient appears ill or their condition is deteriorating, you should act quickly to provide the necessary care.

General Guidelines for Medical Emergencies

When responding to a medical emergency, follow these steps to assess the situation and provide care:

- Ensure Scene Safety: Confirm that the environment is safe for you, the patient, and others before proceeding.

- Form a General Impression: Observe the patient’s overall condition to identify any immediately life-threatening issues, such as severe bleeding or unconsciousness.

- Primary Assessment: Check for and address life-threatening conditions involving airway, breathing, or circulation.

- Gather Patient History: Use the SAMPLE acronym to collect critical information (Symptoms, Allergies, Medications, Past medical history, Last oral intake, Events leading up to the incident).

- Secondary Assessment: Perform a head-to-toe examination to gather additional information about the patient’s condition.

- Obtain Vital Signs: Monitor the patient’s breathing, pulse, and other vital indicators.

- Call for Advanced Help: Ensure that more advanced medical personnel are on their way.

- Provide Comfort: Help the patient rest in a position of comfort and prevent them from becoming too hot or cold.

- Offer Reassurance: Calm and reassure the patient to reduce anxiety and help stabilize their condition.

- Prevent Further Harm: Take measures to avoid any worsening of the patient’s situation.

- Administer Oxygen: Provide supplemental oxygen if needed and if your local protocols allow.

These steps will guide you through the care process for most medical emergencies, allowing you to respond effectively and confidently in any situation.

Activity

Situational awareness is key to identifying scene hazards and potentially unsafe situations involving hazardous materials. In the box, below identify one or more potential hazardous materials.

| Scenario | Possible Hazardous Materials |

|---|---|

| 3-year-old female found unresponsive, in the garage with an unlabeled empty container | |

| 45-year-old male with shortness of breath after working with pesticides | |

| A couple living in a small trailer start experiencing headache and dizziness during a cold snap. |

A Rural Healthcare Medical Emergency

Scene Arrival

You are the EMR for a rural ambulance service. It’s a hot summer afternoon, and you are dispatched to a remote farming area where a Spanish-speaking male, approximately 60-years old, has been reported wandering near a field. Upon arrival, you find the man sitting on the edge of a dirt road, confused and visibly agitated. His clothing is soaked with sweat, and he appears disoriented.

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ An older man is sitting on the side of a gravel road, looking overheated and disoriented](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/68/2025/04/aitubo-2-701x1024.jpg)

Initial Assessment

The man looks at you with apprehension but does not respond when you speak English. Recognizing the language barrier, you use basic Spanish phrases like “¿Está bien?” (Are you okay?) and “¿Cómo se llama?” (What is your name?). He mumbles something unintelligible but eventually says, “José.” He doesn’t seem to know where he is or why he’s there.

You perform a quick primary assessment:

- Airway: Clear.

- Breathing: Normal but rapid.

- Circulation: Skin is hot and sweaty, but pulses are strong.

His vital signs are:

- Pulse: 100 bpm (regular)

- Respiratory rate: 20 breaths per minute

- Blood pressure: 120/80 mmHg

- Skin: Cool, clammy, and pale

Gathering Information

You check his surroundings and notice a pile of picked vegetables nearby. It seems he was working in the fields. A bystander mentions he’s part of a local migrant farming crew but doesn’t know him personally.

From your observations, his symptoms and history raise concerns about heat exhaustion or possibly hypoglycemia given his confusion.

Immediate Actions

- Positioning:

You help José sit in a shaded area to cool down. - Hydration:

You provide sips of cool water while carefully monitoring his ability to swallow. - Cool Down:

You remove his hat and place a cool, damp cloth on his neck and forehead. - Ongoing Assessment:

While waiting for advanced medical personnel, you reassess his LOC and check for additional signs of dehydration or shock. You ask simple yes/no questions in Spanish, such as “¿Dolor en el pecho?” (Chest pain?) or “¿Está mareado?” (Are you dizzy?) to identify further symptoms.

Additional Information

While waiting, you consider other possible causes of his condition:

- Low Blood Sugar (Hypoglycemia): He might not have eaten recently, which is common among laborers during long work shifts.

- You ask nearby workers if José ate lunch or has diabetes. If safe and appropriate, you consider offering him oral glucose or a sugary drink if symptoms worsen.

- Heat-Related Illness: The combination of hot weather, physical labor, and profuse sweating strongly suggests heat exhaustion.

Hand-Off to Advanced Medical Personnel

When paramedics arrive, you provide a thorough hand-off:

- The patient is a 60-year-old Spanish-speaking male, identified as José.

- He is confused, sweating profusely, and showing signs consistent with heat exhaustion or hypoglycemia.

- His vital signs and immediate care measures are relayed.

- You share that he is part of a migrant farming crew and may have limited access to food, water, or medical care.

Reflections on Rural Healthcare Challenges

This incident highlights the unique challenges of rural healthcare:

- Language Barriers: Being prepared with basic Spanish phrases helped establish communication.

- Access to Care: Migrant workers often have limited healthcare access, making prehospital care crucial.

- Environmental Risks: Rural settings expose workers to heat, dehydration, and long hours without breaks.

As an EMR, your quick thinking and culturally sensitive approach ensured that José received timely and appropriate care, possibly preventing a life-threatening emergency.

10.3 Introduction to Cardiac Emergencies

Cardiac emergencies, including heart attacks and cardiac arrest, can occur anywhere, including rural communities where access to advanced medical care may be delayed. This chapter prepares EMRs to handle such emergencies effectively while also addressing the unique challenges of rural healthcare, such as longer response times, limited resources, and extended distances to hospitals.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Circulatory System

The Heart

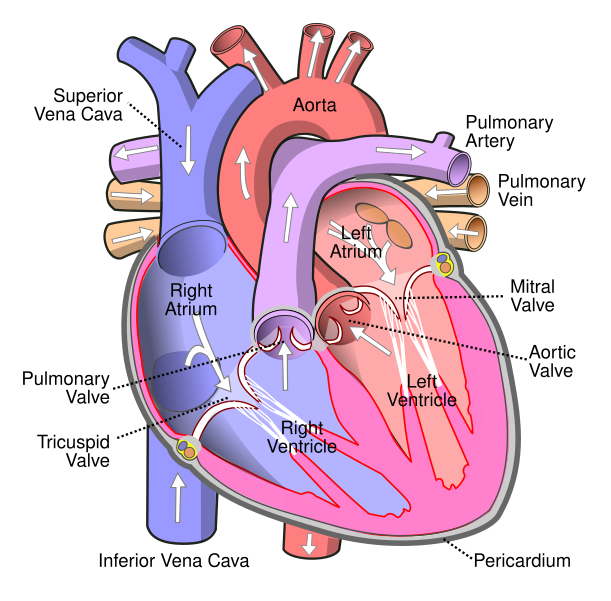

The heart, a fist-sized muscular organ, functions as a pump to circulate blood. Positioned centrally in the chest, it is protected by the sternum, ribs, and spine. It has four chambers: the right and left atria, and the right and left ventricles. Blood flows through these chambers in a one-way system regulated by valves.

- Right Atrium: Receives oxygen-depleted blood from the body.

- Right Ventricle: Pumps blood to the lungs for oxygenation.

- Left Atrium: Receives oxygen-rich blood from the lungs.

- Left Ventricle: Pumps oxygen-rich blood to the rest of the body.

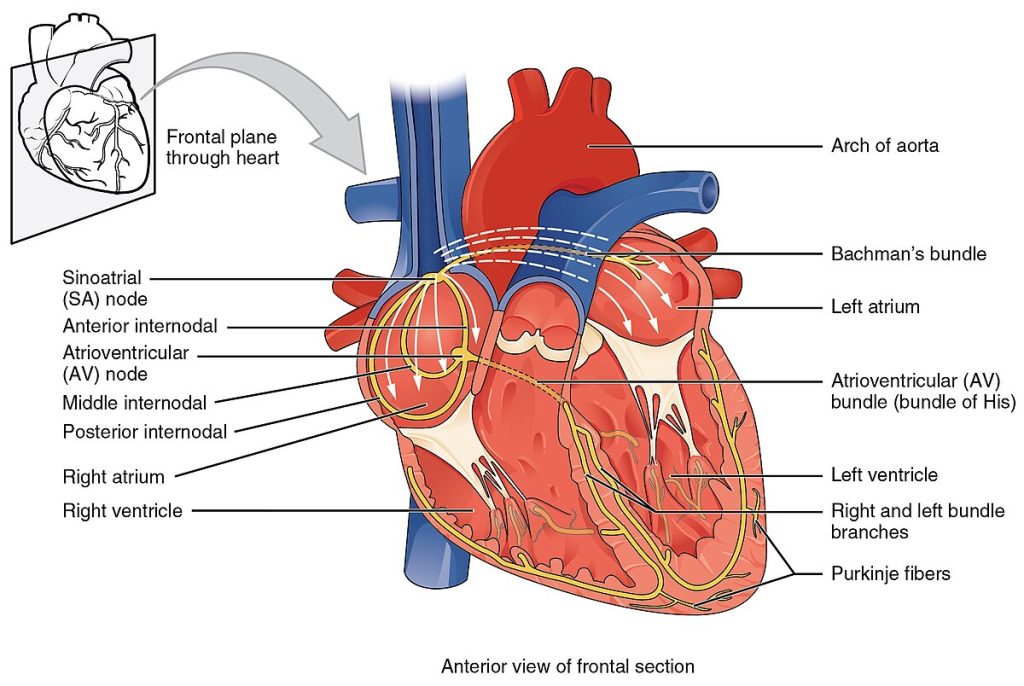

Electrical System

The heart’s electrical impulses originate at the sinoatrial (SA) node, pass through the atrioventricular (AV) node, and travel via Purkinje fibers to the ventricles, prompting contraction. This rhythm is crucial for maintaining circulation.

In rural settings, limited healthcare access increases the importance of community education about heart health and the availability of basic lifesaving tools like AEDs.

Physiology of the Circulatory System

The circulatory system ensures oxygen and nutrients are delivered to cells and waste products are removed. This process, called perfusion, depends on a functioning heart, healthy blood vessels, and adequate blood oxygen levels.

Pathophysiology of the Circulatory System

Cardiovascular Disease

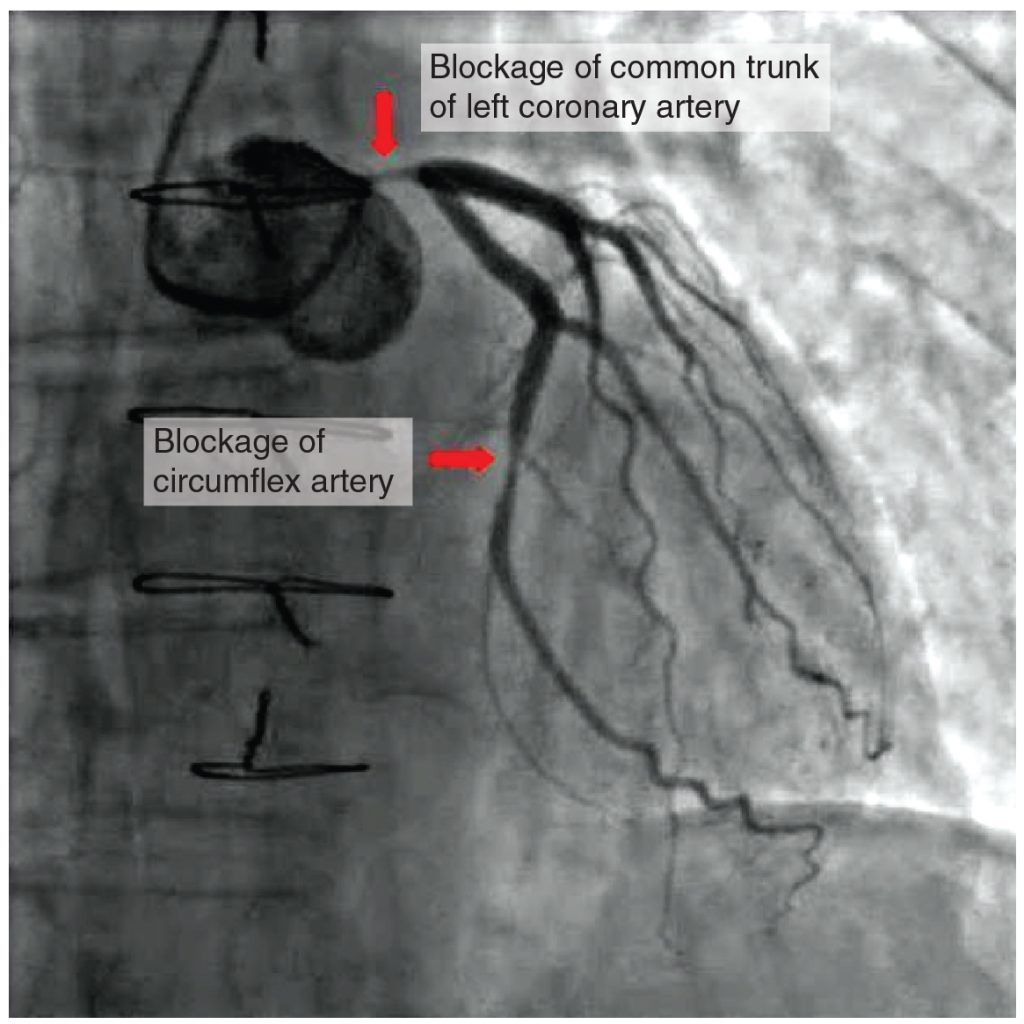

Cardiovascular disease remains the leading cause of death in the U.S. Common conditions include coronary heart disease (CHD) and stroke. CHD, often caused by atherosclerosis, results from cholesterol and plaque buildup in arteries, narrowing them and reducing blood flow.

Rural communities face unique challenges with CHD management, including limited access to diagnostic tools like electrocardiograms (ECGs) and specialist care. Preventive education and timely response protocols are crucial.

Heart Attack (Myocardial Infarction)

A heart attack, or myocardial infarction, occurs when coronary arteries become blocked, leading to tissue damage. Symptoms include:

- Chest pain or discomfort.

- Pain radiating to the arms, back, or jaw.

- Shortness of breath or nausea.

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ A middle aged woman with hand on her chest, a look of discomfort on her face](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/68/2025/04/aitubo-3-701x1024.jpg)

Silent heart attacks, particularly in older adults, may present with atypical symptoms like weakness, fatigue, or indigestion, emphasizing the importance of thorough assessment in rural areas where follow-up care may be delayed.

Diabetes and “Silent” Heart Attacks

People with diabetes face unique challenges, as nerve damage may dull their ability to feel typical heart attack symptoms like chest pain. Instead, they might experience unexplained fatigue or subtle discomfort. These “silent” heart attacks often go unnoticed until detected through diagnostic tests, underscoring the importance of regular monitoring in diabetic patients.

Women and Atypical Heart Attack Symptoms

Heart attacks in women can manifest differently than in men. While chest pain is common, women are more likely to report symptoms like jaw pain, nausea, back discomfort, or extreme fatigue. For instance, consider a mother feeling unusually tired and dismissing it as stress, only to later learn it was a heart attack. These less obvious signs often delay medical attention, emphasizing the need for awareness and education.

Cardiac Arrest

Cardiac arrest occurs when the heart stops functioning as a pump, often caused by arrhythmias or oxygen deprivation. Prompt CPR and AED use can significantly increase survival rates.

Considerations for Specific Populations

Older Adults

Older adults may experience subtle or atypical symptoms of cardiac emergencies, such as fatigue or abdominal pain, making early detection more challenging. In rural areas, EMRs must rely on careful observation and patient history to identify possible cardiac events.

Pediatrics

Cardiac emergencies in children and infants are often secondary to respiratory issues or traumatic injuries. Causes may include:

- Airway obstruction or respiratory distress.

- Traumatic events like drowning or electrocution.

- Congenital heart defects.

Rural Adaptations

- Fact: Cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of death in the U.S.

- Rural Adaptation: Equip communities with AEDs and provide ongoing CPR training to compensate for delayed EMS arrival times.

Understanding Specific Cardiovascular Emergencies

The circulatory system is complex, and when emergencies arise, quick recognition and intervention are vital. Let’s delve into some of the specific cardiovascular conditions and how they can be managed effectively.

Angina Pectoris: A Cry for More Oxygen

Angina pectoris translates to “chest pain” and typically occurs when the heart demands more oxygen than the narrowed coronary arteries can supply. Imagine a person jogging uphill, their heart working harder to keep up, and then feeling a gripping chest discomfort. This is how angina presents—often triggered by physical exertion or emotional stress. Thankfully, angina is temporary and manageable. Stopping the activity and using prescribed medication, like nitroglycerin, usually eases the pain. Nitroglycerin works by dilating blood vessels, improving oxygen flow to the heart.

A helpful analogy: Angina is like a “yellow light” at a traffic signal, warning of potential danger ahead. It’s not a full-blown heart attack but indicates that action is needed to prevent one.

Arrhythmias: A Misstep in the Heart’s Rhythm

Arrhythmias occur when the heart’s electrical system malfunctions, disrupting its regular rhythm. While some arrhythmias are harmless, others signal severe issues that could lead to heart disease, stroke, or sudden cardiac death.

One common type is atrial fibrillation (AFib), where the heart’s upper chambers (atria) beat irregularly and out of sync with the lower chambers (ventricles). This reduces the heart’s efficiency, akin to a drumline playing out of rhythm at a parade. Though not usually life-threatening, AFib raises the risk of stroke. Advanced treatments like medications or electrical interventions can restore or control the rhythm.

Congestive Heart Failure: The Overloaded Pump

In congestive heart failure (CHF), the heart struggles to pump blood effectively, leading to fluid buildup throughout the body. Picture a sump pump failing to remove water from a flooded basement—fluid collects where it shouldn’t. Patients often experience swelling in the legs, ankles, and feet, along with weight gain and difficulty breathing. Managing CHF involves medications, lifestyle changes, and in severe cases, medical devices or surgery.

Hypertension: The Silent Killer

High blood pressure, or hypertension, quietly damages blood vessels over time. Many patients are unaware they have it, earning it the nickname “silent killer.” Factors like sodium intake, stress, and certain medications can exacerbate hypertension. In secondary cases, underlying conditions like kidney disease or adrenal tumors are to blame. Left untreated, hypertension can lead to heart attacks or strokes.

| Category | Blood Pressure Reading |

|---|---|

| Normal | 90 to 119/60 to 80 |

| Elevated | 120 to 129 systolic and ≤80 diastolic |

| Stage I hypertension | 130 to 139 systolic or 80 to 89 diastolic |

| Stage II hypertension | ≥140 systolic or ≥90 diastolic |

Recognizing and Acting on Cardiac Emergencies

Quick recognition of heart attack symptoms can save lives. Persistent chest pain, shortness of breath, and pale or clammy skin are key warning signs. Even brief or intermittent chest discomfort should not be ignored. Ask patients open-ended questions like, “Can you describe how you feel?” to understand their experience better.

If a heart attack is suspected:

- Call for Emergency Help: Activate EMS, if not already done.

- Calm the Patient: Help them rest and reduce stress.

- Administer Aspirin: If allowed and appropriate, aspirin can slow damage by thinning the blood. Ensure the patient chews it fully for faster absorption.

- Consider Oxygen: If evidence of respiratory distress or hypoxia.

- Prepare for CPR: If the heart stops, cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) and an automated external defibrillator (AED) may be necessary.

Aspirin as a Lifesaving Tool

For patients showing early heart attack symptoms, aspirin can be a game-changer. This common medication prevents blood clots from worsening by inhibiting platelet aggregation. Always verify that the patient has no allergies, or active bleeding. A simple dose of 2 to 4 low-dose tablets can make all the difference.

Important Note: Aspirin is not interchangeable with NSAIDs like ibuprofen or acetaminophen. Coated aspirin is acceptable as long as it is chewed thoroughly.

Skills for Cardiac Emergencies

Cardiopulmonary Resuscitation (CPR)

See additional details in the Resuscitation section.

- One-Responder CPR: Deliver high-quality compressions at a rate of 100-120 per minute. Alternate chest compressions with rescue breaths (30:2 ratio) if a barrier device or BVM is available.

- Two-Responder CPR: Alternate roles to minimize fatigue, maintaining the same compression-to-ventilation ratio.

Using an AED

- Turn on the AED and follow prompts.

- Attach electrode pads to the bare chest as indicated.

- Ensure no one touches the patient during rhythm analysis or shock delivery.

Key Takeaways

- Early recognition and rapid action are crucial for cardiac emergencies, especially in rural areas.

- Cardiac emergencies may present without chest pain.

- High-quality CPR and defibrillation can bridge the gap until advanced care arrives.

- Effective communication and adaptability are critical in rural settings with limited resources.

Review Questions

- Describe the difference between a heart attack/myocardial infarction and cardiac arrest.

- What steps would you take when responding to a cardiac emergency in a remote location?

- How does rural healthcare impact the timing and effectiveness of CPR and AED use?

10.4 The Endocrine System and Diabetic Emergencies for Emergency Medical Responders

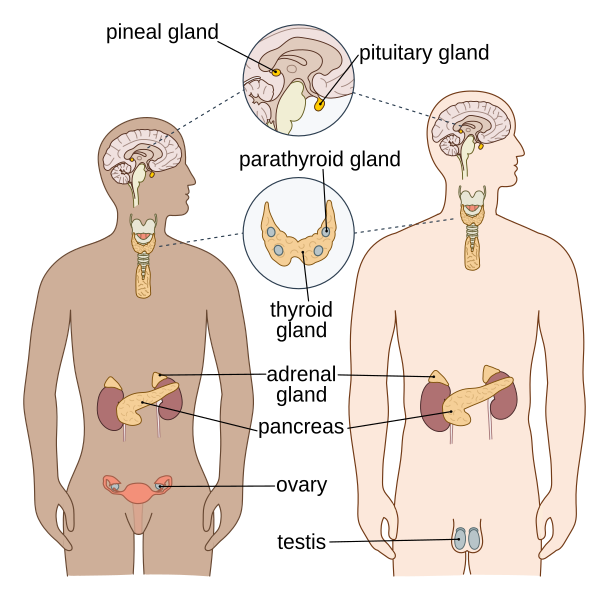

The endocrine system, composed of ductless glands, is integral to maintaining the body’s internal balance and regulating various functions. These glands secrete hormones that influence physical activity, growth, metabolism, and behavior. As responders, understanding endocrine anatomy, physiology, and common emergencies, such as diabetes-related crises, is crucial for effective patient care.

Anatomy of the Endocrine System

The endocrine system includes several essential glands:

- Hypothalamus and Pituitary Gland (Brain):

- The pituitary gland, the “master gland,” regulates growth and controls other glands.

- The hypothalamus acts on the pituitary gland to influence body functions.

- Thyroid Gland (Neck):

- Regulates metabolism, growth, development, and nervous system activity.

- Adrenal Glands (Above Kidneys):

- Secrete epinephrine and norepinephrine.

- Also regulate kidney function and balance water and electrolytes.

- Pancreas:

- Contains the Islets of Langerhans, which secrete:

- Insulin: Lowers blood glucose and helps cells utilize glucose.

- Glucagon: Raises blood glucose levels.

- Contains the Islets of Langerhans, which secrete:

- Gonads (Ovaries and Testes):

- Control reproduction and sex characteristics.

- Pineal Gland (Brain):

- Regulates sleep and wake patterns.

Physiology of the Endocrine System

The endocrine system regulates vital functions, including:

- Blood Glucose Control:

The pancreas plays a key role by producing insulin and glucagon to balance glucose levels in the blood. - Sympathetic Nervous System Activation:

Adrenaline and norepinephrine manage the “fight or flight” response, including increased heart rate, vessel constriction, and respiratory muscle relaxation. - Electrolyte and Water Balance:

Glands like the adrenal and pituitary glands regulate fluids and electrolytes to maintain homeostasis.

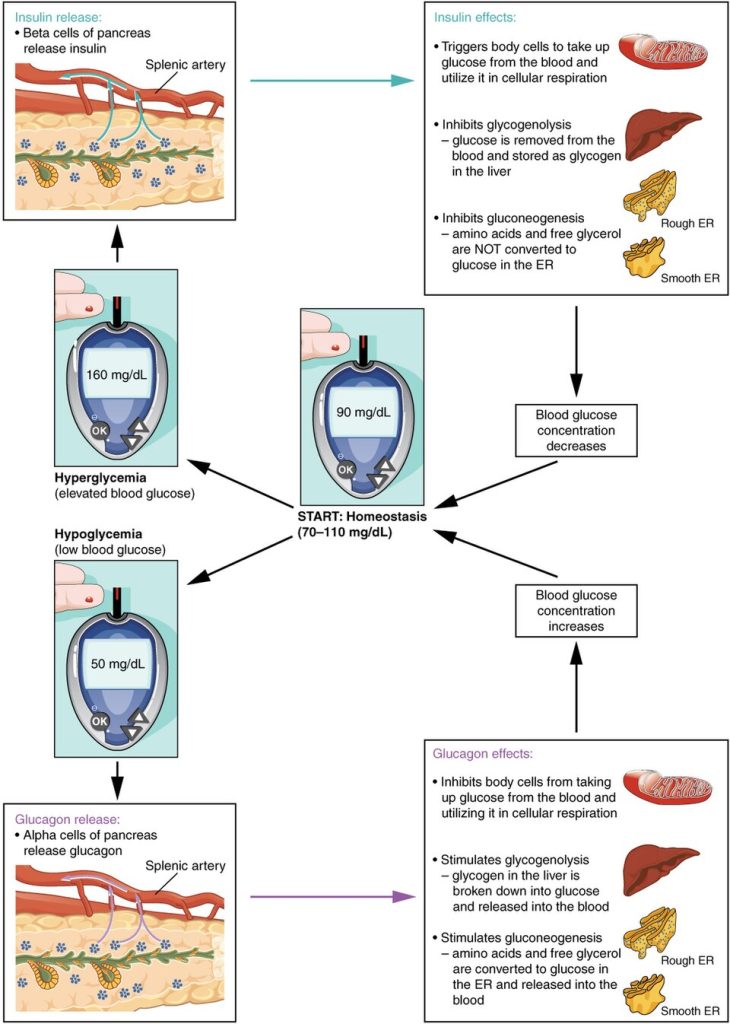

Homeostatic Regulation of Blood Glucose Levels. Blood glucose concentration is tightly maintained between 60-70 mg/dL and 100-110 mg/dL depending on the reference. Similar to heart rates, the value may be somewhat outside of the range, but not require treatment until significantly abnormal. If blood glucose concentration rises, insulin is released, which stimulates body cells to remove glucose from the blood. If blood glucose concentration drops, glucagon is released, which stimulates body cells to release glucose into the blood.

Diabetes-Related Emergencies

Diabetes mellitus is a chronic condition resulting from insufficient insulin production or ineffective insulin utilization, leading to elevated blood glucose levels. Unmanaged diabetes can lead to emergencies requiring immediate attention.

- Hypoglycemia (Low Blood Sugar):

- Causes: Too much insulin, skipping meals, or excessive exercise.

- Signs and Symptoms:

- Sweating, shaking, and confusion.

- Rapid pulse, weakness, and irritability.

- Progression to seizures or unconsciousness if untreated.

- Treatment:

- Provide glucose (oral tablets, juice, or candy) if the patient is conscious.

- If unconscious, requires advanced care.

- Example: A 35-year-old man at a gym becomes confused and collapses after skipping breakfast.

- Hyperglycemia (High Blood Sugar):

- Causes: Insufficient insulin, excessive carbohydrate intake, or infection.

- Signs and Symptoms:

- Excessive thirst, frequent urination, fatigue, and blurred vision.

- Sweet-smelling breath (ketones) in severe cases.

- Treatment:

- Position the patient for comfort and arrange immediate transport.

- Example: A 60-year-old woman at home becomes lethargic and complains of extreme thirst over several days.

- Diabetic Ketoacidosis (DKA):

- Causes: A severe lack of insulin, often in Type 1 diabetes.

- Signs and Symptoms:

- Deep, rapid breathing (Kussmaul respirations).

- Nausea, abdominal pain, confusion, and fruity-smelling breath.

- Signs of dehydration and potential progression to shock.

- Report of being very thirsty, drinking a lot of water.

- Treatment:

- Ensure airway patency and prevent aspiration.

- Monitor for shock and arrange for rapid transport.

- Example: A 22-year-old college student exhibits confusion and labored breathing after missing insulin doses.

- Hyperosmolar Hyperglycemic State (HHS):

- Causes: Uncontrolled Type 2 diabetes, often triggered by illness or dehydration.

- Signs and Symptoms:

- Extremely high blood glucose, severe dehydration, and altered mental status.

- Report of being very thirsty, drinking a lot of water.

- Treatment:

- Provide airway support and monitor vital signs.

- Arrange immediate transport to manage dehydration and hyperglycemia.

- Example: A 70-year-old man in a rural nursing home becomes unresponsive, with a history of poor diabetes management.

Special Considerations

- Children:

Children with diabetes are more prone to hypoglycemia due to erratic eating and activity patterns. Pediatric DKA requires urgent attention, as it can develop rapidly.

Example: A 10-year-old girl on a school trip becomes lethargic and irritable after skipping lunch. - Older Adults:

Older adults may have subtle symptoms, making hyperglycemia or hypoglycemia harder to detect. Dehydration and infections can exacerbate diabetes-related emergencies.

Example: An 80-year-old woman at a care facility becomes confused, with dry mucous membranes and high blood glucose.

Emergency Medical Response

- Assessment:

- Collect a detailed SAMPLE history, focusing on medications, blood glucose monitoring, and recent meals or insulin use.

- Observe for signs of dehydration, confusion, or abnormal respiratory patterns.

- Treatment:

- For Hypoglycemia: Administer glucose if conscious; arrange transport if unconscious.

- For Hyperglycemia, DKA, or HHS: Stabilize airway, monitor vital signs, and arrange immediate transport.

- Transport:

- Hand-off report to transporting crew with vital signs and glucose level.

Conclusion

By recognizing the signs and symptoms of endocrine emergencies like diabetes-related crises, responders can provide timely, lifesaving interventions. Knowledge of the endocrine system’s anatomy and physiology ensures a holistic approach to patient care in both urban and rural settings

10.5 Abdominal Emergencies and the Digestive System for Emergency Medical Responders

The abdominal cavity houses multiple critical organs involved in digestion, circulation, and other essential processes. Abdominal pain or emergencies can stem from issues in these organs and may range from mild discomfort to life-threatening conditions. For EMRs, understanding the anatomy and physiology of the digestive system and recognizing common abdominal emergencies is vital to providing effective care.

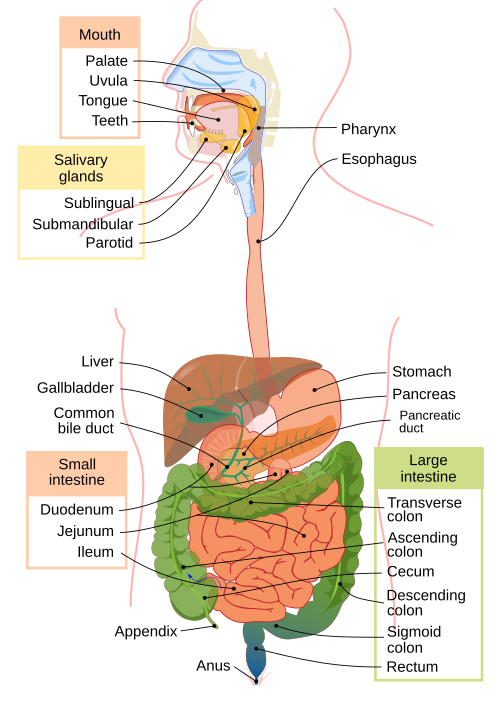

Anatomy of the Digestive System

The digestive system, or gastrointestinal (GI) system, is responsible for breaking down food, absorbing nutrients, and eliminating waste. It consists of two main components:

- The Alimentary Tract (Food Passageway):

- Includes the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine.

- Accessory Organs:

- These include the liver, gallbladder, and pancreas, which assist in digestion.

Digestive Process:

- Food enters the digestive system through the mouth.

- Digestion begins with mastication (mechanical break down of food by chewing) and addition of enzymes in saliva to start degradation of food.

- Break down of food continues in the stomach, where hydrochloric acid is added and mechanical turning breaks the elements down further.

- From the stomach, partially digested food moves to the small intestine for nutrient absorption. Enzymes and chemicals are added from the gallbladder, liver and pancreas.

- The hepatic portal system transfers nutrients and toxins from the small intestine to the liver, where they are processed.

- Waste products enter the large intestine, where water is absorbed, and the remaining waste is excreted through the rectum and anus.

Accessory Organs and Their Functions:

- Liver: Produces bile to digest fats and processes toxins and nutrients.

- Gallbladder: Stores bile.

- Pancreas: Produces digestive enzymes and hormones, including insulin and glucagon, essential for blood glucose regulation.

Common Abdominal Emergencies

Abdominal pain is a frequent medical complaint, often challenging to assess due to the range of potential causes. Abdominal emergencies can originate from digestive, circulatory, or other organ systems within the abdominal cavity.

- Acute Abdomen:

- A sudden onset of severe abdominal pain that requires immediate medical attention. Causes may include appendicitis, bowel obstruction, or ectopic pregnancy.

- Gastrointestinal Bleeding:

- Causes: Esophageal varices, peptic ulcers, gastritis, diverticulitis, or hemorrhoids.

- Signs and Symptoms:

- Vomiting blood (bright red or coffee-ground appearance).

- Coffee-ground appearance indicates exposure to stomach acid

- Bloody or black, tarry stools.

- Dark tarry-appearing stool also indicates contact with stomach acid, then passed through the GI tract.

- Pale skin appearance, fatigue, and shortness of breath.

- Vomiting blood (bright red or coffee-ground appearance).

- Treatment: Stabilize airway, monitor vitals, and arrange transport promptly. Severe bleeding may require transfusion or surgery.

- Appendicitis:

- Cause: Inflammation of the appendix.

- Signs and Symptoms:

- Pain starting near the navel and shifting to the lower right abdomen.

- Nausea, fever, and loss of appetite.

- Treatment: Arrange transport for surgical intervention.

- Bowel Obstruction:

- Cause: Blockage in the intestines due to scar tissue, tumors, or impacted stool.

- Signs and Symptoms:

- Crampy abdominal pain, bloating, nausea, and vomiting.

- Inability to pass stool or gas.

- Treatment: Position for comfort and arrange transport.

- Gallbladder Emergencies (Cholecystitis):

- Cause: Inflammation due to gallstones.

- Signs and Symptoms:

- Severe pain in the upper right abdomen, often radiating to the shoulder.

- Nausea, vomiting, and fever.

- Treatment: Monitor for shock and arrange transport promptly.

Signs and Symptoms of Abdominal Emergencies

When assessing a patient with abdominal pain, assume the condition is serious and observe for:

- Pain Characteristics: Colicky (waves) or localized tenderness.

- Abdominal Changes: Rigidity, distension, or visible guarding.

- Associated Symptoms: Nausea, vomiting, fever, blood in stool or vomit, rapid pulse, or signs of shock.

- Movement: Reluctance to move or pain worsening with movement.

Assessment and Care for Abdominal Pain

- Initial Assessment:

- Monitor airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs).

- Look for signs of aspiration if vomiting is present.

- Physical Examination:

- Palpate the four abdominal quadrants last, starting away from the pain.

- Observe for rigidity, distension, or tenderness. Avoid over-palpation.

- Remember the abdominal anatomy and organs.

- Care Considerations:

- Do not administer food, drink, or medication unless directed by advanced medical personnel.

- Place the patient in a comfortable position, preferably on their side if nausea or vomiting is present.

- Monitor for shock (pale skin, rapid pulse, low blood pressure) and keep the patient warm.

Special Considerations

- Children:

Abdominal pain in children may indicate conditions such as appendicitis, gastroenteritis, or ingestion of toxic substances. Vomiting and diarrhea are significant concerns due to dehydration risks.- Assess mental status, abdominal tenderness, and vital signs.

- Female patients of child-bearing age (approximately 15 to 49 years old per WHO, or puberty to menopause):

Always consider ectopic pregnancy..- Especially if unstable with hypotension and tachycardic.

- Older Adults:

Older patients may have vague symptoms with serious conditions such as diverticulitis, bowel obstruction, or mesenteric ischemia. Dehydration and electrolyte imbalances from vomiting or diarrhea can worsen outcomes.-

- Monitor for subtle changes in mental status or physical findings.

-

Conclusion

Understanding the anatomy and physiology of the digestive system provides a foundation for identifying and managing abdominal emergencies. By recognizing signs of serious conditions and providing timely interventions, responders play a critical role in improving patient outcomes during these emergencies.

10.6 Eye, Ear, Nose and Throat (EENT) Emergencies for Emergency Medical Responders

EENT emergencies encompass a range of conditions that can affect vision, breathing, swallowing, or overall airway function. Prompt recognition and intervention are vital to prevent serious complications. Below is an overview of common EENT emergencies, their signs, and management considerations in prehospital care.

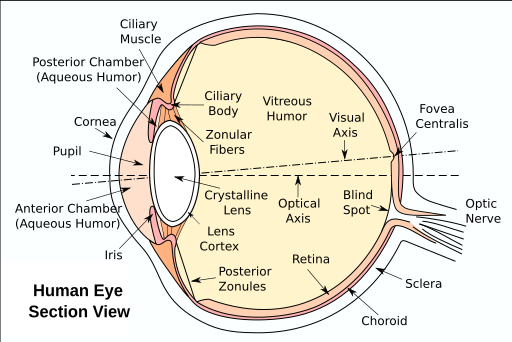

Common Eye Emergencies

A special treatment consideration for eye emergencies is the need to cover BOTH eyes if significant pain or injury. The eyes move in a coordinated manner. Then, also realize your patient will not be able to see, and you will need to verbally warn them of any interaction, further treatment, or impending movement (such as lifting to the ambulance cot).

- Foreign Bodies in the Eye:

- Cause: Dust, metal shavings, or other debris entering the eye.

- Signs: Pain, redness, tearing, and sensation of something in the eye.

- Management:

- Do not rub the eye.

- Gently flush with sterile saline or water if the foreign body is visible and superficial.

- Cover the eye with a sterile dressing and arrange transport for further evaluation.

- Chemical Burns:

- Cause: Exposure to acidic or alkaline substances.

- Signs: Severe pain, redness, swelling, and blurry vision.

- Management:

- Immediately flush the eye with copious amounts of water or saline for at least 15–20 minutes.

- Avoid contaminating the unaffected eye.

- Cover with a sterile dressing and arrange transport promptly.

- Blunt Trauma:

- Cause: Direct impact to the eye or surrounding area.

- Signs: Swelling, bruising, vision changes, or blood in the eye (hyphema).

- Management:

- Protect the eye with a shield or sterile dressing.

- Avoid applying pressure.

- Arrange transport for further evaluation, watching for signs of associated head injury.

- Penetrating Eye Injuries:

- Cause: Sharp objects causing puncture wounds to the eye.

- Signs: Severe pain, vision loss, or visible object protruding from the eye.

- Management:

- Do not remove the object.

- Stabilize the object with gauze and a protective cover.

- Keep the patient calm and arrange transport urgently.

- Acute Angle-Closure Glaucoma:

- Cause: Sudden increase in intraocular pressure.

- Signs: Severe eye pain, headache, nausea, vomiting, and blurry vision.

- Management:

- Keep the patient in a semi-reclined position.

- Arrange transport urgently as this is a vision-threatening emergency.

Common Ear Emergencies

Add ear diagram

- Foreign Bodies in the Ear:

- Cause: Small objects like beads, insects, or food lodged in the ear canal.

- Signs: Pain, hearing loss, or visible object in the ear.

- Management: Avoid attempts to remove objects unless visible and superficial. Arrange transport for further care.

- Ear Trauma:

- Cause: Direct impact or penetrating injuries to the ear.

- Signs: Bleeding, swelling, or deformity.

- Management: Apply a sterile dressing to control bleeding. Avoid probing the ear canal. Arrange transport promptly.

Common Nose Emergencies

Add nose diagram

- Nosebleeds (Epistaxis):

- Cause: Trauma, dry air, or hypertension.

- Signs: Bleeding from one or both nostrils.

- Management:

- Pinch the nostrils shut and lean the patient forward.

- Avoid tilting the head back.

- If bleeding persists, arrange transport for medical care.

- Foreign Bodies in the Nose:

- Cause: Small objects lodged in the nasal passage, often in children.

- Signs: Nasal congestion, bleeding, or foul odor.

- Management: Do not attempt to remove objects unless superficial. Arrange transport for medical evaluation.

Common Throat Emergencies

Add throat diagram

- Airway obstruction with stridor:

- Description: A high-pitched sound caused by partial airway obstruction.

- Types:

- Inspiratory: From obstructions near the larynx and vocal cords (e.g., croup, epiglottitis).

- Expiratory: From obstructions in the lower airway, less common. May actually be unrecognized wheezing.

- Biphasic: From more severe obstructions in the trachea.

- Management: Keep the patient calm to reduce anxiety, administer oxygen if needed, and prepare for airway intervention.

- Croup:

- Cause: Viral infection leading to swelling in the airway, commonly affecting children aged 6–24 months.

- Signs: Stridor, barking cough, and difficulty breathing.

- Management: Keep the child calm, provide oxygen, and arrange transport promptly for further care.

- Acute Epiglottitis:

- Cause: Bacterial infection causing swelling of the epiglottis, leading to potential airway obstruction.

- Signs: Rapid onset of sore throat, difficulty swallowing, drooling, and stridor.

- Management: Avoid agitating the patient, keep them upright, and arrange transport urgently. Do not attempt to visualize the throat as it may worsen the condition.

- Foreign Body Aspiration:

- Cause: Objects (e.g., food, small toys) lodged in the airway, typically in children aged 1–3 years.

- Signs: Sudden choking, stridor, wheezing, and difficulty breathing.

- Management: Perform back blows and chest thrusts in infants or abdominal thrusts in older children and adults. Monitor for airway compromise and arrange transport promptly.

- Tracheostomy Emergencies:

- Cause: Dislodgement, obstruction, or infection of the tracheostomy tube.

- Signs: Respiratory distress, gurgling sounds, or complete airway blockage.

- Management: Assist caregivers to clear the obstruction, and suction if necessary. Provide oxygen and arrange transport for further care.

- Bleeding Tonsils (Post-Tonsillectomy Hemorrhage):

- Cause: Bleeding after a tonsillectomy, occurring within the first week post-surgery.

- Signs: Coughing up blood, vomiting blood, or difficulty breathing.

- Management: Keep the patient upright to prevent aspiration, monitor for shock, and arrange transport urgently.

- Deep Neck Space Abscesses:

- Cause: Infections from dental or upper respiratory tract sources.

- Signs: Swelling, fever, difficulty swallowing, and potential airway compromise.

- Management: Allow for position of comfort, ensure the airway is clear, administer oxygen as needed, and arrange transport for hospital-based treatment.

Assessment and Management Tips for EENT Emergencies

- Protect Airway and Vision:

- Prioritize airway management in ENT emergencies and protect the eyes in eye-related emergencies.

- Calm and Reassure:

- Keeping the patient calm can help prevent worsening of symptoms, especially in cases of stridor or eye trauma.

- Oxygenation:

- Provide supplemental oxygen when airway compromise or respiratory distress is suspected.

- Transport:

- Arrange transport to advanced care, especially for penetrating injuries, chemical burns, or airway obstruction.

Conclusion

EENT emergencies can quickly become life-threatening. EMRs must recognize signs, stabilize the patient, and ensure prompt transport for specialized care. Early intervention can significantly improve outcomes in these critical situations.

References:

American Red Cross. (2017). Emergency medical response.

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2024). Heart disease facts. https://www.cdc.gov/heart-disease/data-research/facts-stats/index.html

Hamper, C., Curtz, C., Edwins, H. A., & Kennel, J. (2023). Oregon EMS psychomotor skills lab manual. OpenOregon. https://openoregon.pressbooks.pub/emslabmanual/chapter/hazardous-materials/

Le Baudour, C., Wesley, K., & Bergeron, J. D. (2018). Emergency medical responder: First on scene (11th ed.). Pearson.

Le Baudour, C., Laurélle, K., & Wesley, K. (2023). Emergency medical responder: First on scene (12th ed.). Pearson.

Sokolovs, D., & Tan, K. W. (2023). Ear, nose, and throat emergencies. Anaesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine, 24(3), 184–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.mpaic.2022.12.022

Images:

Figure 10.1: Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/

Figure 10.2: ”Diagram_of_the_human_heart_(cropped)” by Wapcaplet is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Figure 10.3: ”2018_Conduction_System_of_Heart” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Figure 10.4: Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/

Figure 10.5: ”2016_Occluded_Coronay_Arteries” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0

Figure 10.6: ”Endocrine_English” by OpenStax & Tomáš Kebert & umimeto.org is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

Figure 10.7: “1822 The Homeostatic Regulation of Blood Glucose Levels.jpg” by OpenStax is licensed under CC BY 4.0.

Figure 10.8: ”Digestive_system_diagram_en” by Mariana Ruiz, Jmarchn is in the Public Domain.

Figure 10.9: ”Eyesection” by user:ZStardust is in the Public Domain.