Chapter 9: Assessment

Jamie Howell, MSN, RN-EMT, CHSE

9.1 Introduction

You’re called to a secluded hiking trail where a 30-year-old male fell from a steep ledge while hiking with his partner. Upon arrival, you see the patient about 20 feet below the trail with visible injuries, including possible fractures. His partner is nearby, calling for help but appears unsteady as his feet slide 3 feet down the narrow trail on loose rocks that are making it slippery. What are your concerns prior to providing these hikers care? Do you need any additional resources?

Learning Objectives

(missing from google doc)

(from COS comparison grid)

15.1. identify common scene hazards

15.2. obtain patient history

15.3. identify chief complaint

15.4. determine if critical life-saving interventions are needed

15.5. apply components of a primary assessment/survey

15.6. perform a primary assessment

15.7. determine if age-related assessment considerations apply

15.8. modify assessment based on patient age

15.9. obtain vital signs

15.10. perform reassessment

15.11. perform secondary assessment

9.2 Scene Assessment

Safety and Resources

When arriving at the scene of an emergency, it’s important to resist the urge to rush in and start helping immediately, especially when the situation involves risks like a dangerous hiking trail. Take the time to assess the environment carefully. By doing so, you can avoid putting yourself or the patient in greater danger, address hazards early, and ensure a more effective response. A thorough scene size-up will help prevent overlooked injuries and ensure that proper resources are called to assist when needed.

As an EMR, it’s crucial to approach each scene with preparation, based on the initial information provided by dispatch. This information can guide you in identifying potential hazards and determining the necessary personal protective equipment (PPE) and equipment. However, always remember that dispatch information may not be complete or fully accurate, so it’s important to stay alert to any additional dangers that may arise upon arrival.

Scene safety should always be your top priority. Upon arrival, assess the environment using all your senses to identify potential hazards, including traffic, unstable structures, hazardous materials, and other dangers. Some risks may be immediately apparent, like fire or violence, while others, like toxic chemicals, might only become evident as you progress in your care.

Once immediate hazards are dealt with, managing the scene, especially in a traffic situation, is essential. If police are not yet on the scene, you may need to assume responsibility for traffic control. Make sure that you have proper reflective bright attire on such as emergency medical gear. Always ensure you are adhering to local guidelines and protocols to keep everyone safe.

How do you typically prepare for handling the unknown risks that might come with emergency scenes, such as hazardous materials or unstable environments?

Traffic

To ensure safe traffic control at an emergency scene, vehicles should be redirected well before they reach the area. Allow enough space for vehicles to slow down and move safely over. Set up warning devices like flares, cones, or signs about 10-15 feet apart, positioned in a slanting line. Be cautious of flammable fluids when placing flares. If the incident is on a curve or hill, begin the warning devices at the curve’s start or hilltop. Emergency vehicles, including ambulances, should park strategically, angling tires away from the care area and ensuring they don’t block other emergency vehicles. In hazardous material or fire situations, maintain a safe distance and position vehicles accordingly, turning on emergency lights to further alert oncoming drivers.

[Need to add this reference link for this section:

https://wisconsindot.gov/Documents/about-wisdot/who-we-are/dtsd/bto/etcsmguidelines2016.pdf

Control

To keep the scene under control, maintain your composure and approach the situation calmly. Walking in a purposeful manner, instead of running, signals authority and helps maintain order. In uncontrolled or disorderly situations, consider setting up a barrier around the scene and appointing a person to ensure bystanders stay at a safe distance.

Situational Awareness

Continually evaluate the scene for potential dangers, as new hazards can emerge. Assign a dedicated safety officer whose primary role is to oversee the overall safety of the scene, ensuring responders and bystanders remain protected throughout the incident.

When responding to an emergency, personal safety is your most important responsibility. Begin by assessing the area carefully, noting the emergency’s location, scope, visible risks, number of patients, and any potentially hazardous behavior from bystanders or patients. Always use appropriate PPE to guard against unexpected hazards. If the area feels unsafe, keep a safe distance and contact additional support, waiting until the scene is secure. Reassess regularly as conditions may change. Avoid any actions beyond your training and always follow protocol to prevent exposure to infectious diseases. Being cautious and prepared can prevent harm to yourself and others and ensure a more effective response.

More information about scene safety and situational awareness is found in EMS Operations.

Personal Protective Equipment (PPE)

PPE is an essential aspect of standard precautions, designed to prevent exposure to infectious agents found in blood and other potentially infectious materials (OPIM). Since body fluids may carry pathogens, these precautions are used universally across healthcare settings for all patients, regardless of infection status.

Key PPE components include:

- Hand Hygiene: Effective cleaning to prevent illness transmission.

- Gloves: Essential for contact with patients.

- Gowns: Extra protection against splashes.

- Masks and Eyewear: Shields to guard facial areas from airborne particles or droplets.

- Breathing Barriers: For safe patient ventilation when required.

**Need to move this: Hand Hygiene Videos need to be added – Should be in Preparatory 1 – in the BSI-PPE section

Section on hand hygiene from Nursing text

4.2 Aseptic Technique Basic Concepts – Nursing Skills – 2e

How to Handwash

When washing with soap and water, the CDC recommends using the following steps. See Figure 4.4[13] for an image of a handwashing poster created by the World Health Organization.

- Wet hands with warm or cold running water and apply facility-approved soap.

- Lather hands by rubbing them together with the soap. Use the same technique as the handrub process to clean the palms and fingers, between the fingers, the backs of the hands and fingers, the fingertips, and the thumbs.

- Scrub thoroughly for at least 20 seconds.

- Rinse hands well under clean, running water.

- Dry the hands using a clean towel or disposable toweling.

- Use a clean paper towel to shut off the faucet.[14]

How to Handrub

When using the alcohol-based handrub method, the CDC recommends the following steps. See Figure 4.3[11] for a handrub poster created by the World Health Organization.

- Apply product to the palm of one hand in an amount that will cover all surfaces.

- Rub hands together, covering all the surfaces of the hands, fingers, and wrists until the hands are dry. Surfaces include the palms and fingers, between the fingers, the backs of the hands and fingers, the fingertips, and the thumbs.

- The process should take about 20 seconds, and the solution should be dry.[12]

Examples:

WHO: How to handwash? With soap and water

https://www.bing.com/videos/riverview/relatedvideo?q=open%20source%20nursing%20textbook%20AND%20Chippewa%20valley%20technical%20college%20AND%20hand%20washing%20resource&view=riverview&mid=54488E64883F754C863754488E64883F754C8637&ajaxhist=0

WHO: How to handrub? With alcohol-based formulation

https://www.bing.com/videos/riverview/relatedvideo?q=open%20source%20nursing%20textbook%20AND%20Chippewa%20valley%20technical%20college%20AND%20hand%20washing%20resource&view=riverview&mid=ADD169BB45C3BB578826ADD169BB45C3BB578826&ajaxhist=0

This is longer and more detailed. There are also videos from CVTC Nursing Program

Hand Hygiene for Healthcare Workers | Hand Washing Soap and Water Technique Nursing Skill

https://www.bing.com/videos/riverview/relatedvideo?q=open+source+nursing+textbook+AND+Chippewa+valley+technical+college+AND+hand+washing+resource&&view=riverview&mmscn=mtsc&mid=667D6F1386F478B7F6E3667D6F1386F478B7F6E3&&aps=0&FORM=VMSOVR

The level of PPE needed depends on the anticipated exposure. These standard precautions prioritize the safety of both healthcare responders and patients, helping prevent the spread of infectious diseases while ensuring effective care.

Scene Control

Ensuring the safety of everyone at an emergency scene, including yourself, bystanders, and patients, is critical. Always keep unauthorized individuals from entering unsafe areas. For patients, assess the situation carefully and avoid moving them unless there’s immediate danger, such as a fire or structural instability. If a patient’s safety is threatened, prioritize moving them without worsening their injuries. However, if the situation is stable, have the patient remain still until fully assessed. Bystanders can also be valuable resources in an emergency. If it’s safe, involve them by gathering information about the incident and any relevant medical history for the patients. They can even assist by aiding in care under guidance. In critical situations, a well-organized approach to scene management, clear communication, and vigilance can create a safer and more controlled environment for everyone involved.

When evaluating an emergency scene, identifying the total number of patients needing care is essential. In straightforward situations, this can be done quickly, but complex incidents, such as a building collapse or crowd surge, may require a detailed search to locate everyone involved. Look for signs, like personal belongings or scattered items, that might indicate where individuals were. Some patients might be silent or unable to call for help, so conduct a thorough scan. Knowing the patient count early helps you gauge the resources needed. If you have more patients than you can assist, request additional support before starting care.

When it’s safe to approach a patient, take note of the surroundings and gather clues to understand what happened, as well as any potential causes of injury (mechanism of injury or MOI) or illness (nature of illness, or NOI). With experience, you’ll become skilled at quickly assessing a scene to anticipate possible health issues you may encounter.

Understanding the mechanism of injury, or the event that caused harm, is critical. Identifying a high energy MOI, such as impacts from sports injuries, high falls, or other types of trauma, can reveal underlying injuries that might not be obvious at first glance.

Scene Size-Up and Safety

Before beginning any assessment, a scene size-up ensures responder and bystander safety. This includes confirming the scene is secure, evaluating the mechanism of injury or illness, counting patients, and assessing resource needs.

Steps in Scene Size-Up

- Scene Safety: Ensure safety for responders, the patient, and others.

- Determine Mechanism of Injury (MOI) or Nature of Illness (NOI): Look for visual clues (e.g., damaged objects, substances, or other signs) to help anticipate injuries.

- Identify All Patients: Double-check for multiple individuals needing care.

- Request Advanced Help if Necessary: Contact additional medical support if patients show severe symptoms, such as unresponsiveness, breathing difficulty, chest pain, severe bleeding, or suspected spine injuries.

- Consider the Need for Cervical Spine Stabilization: Is the patient on the ground or not completely alert?

9.3 Primary Assessment

Case Example

Your EMS unit responds to a scene. When you arrive you find a young adult slumped over in a chair, with shallow breathing and a faint pulse. Friends at the scene say he may have overdosed on opioids. How do you assess and stabilize the patient? What equipment or medications might you consider? What are your first steps?

In an emergency, the initial assessment is critical for identifying any life-threatening conditions and providing immediate, targeted care. This rapid assessment involves quickly forming a general impression of the patient, checking responsiveness, and assessing airway, breathing, and circulation (ABCs).

After reviewing these skills, students should be able to: [Where do these belong? At the beginning of the chapter or this section?]

- Conduct a primary assessment

- Evaluate levels of consciousness

- Use techniques like the head-tilt/chin-lift or jaw-thrust to open the airway

- Apply a resuscitation mask for assisted breathing

- Evaluate for adequate circulation

National Registry of EMTs Assessment Check Sheets:

General Impression and Immediate Life Threats

The general impression of a patient is crucial to starting an effective primary assessment. Once the scene is deemed safe, your first goal is to quickly understand the patient’s condition. This involves observing the patient’s appearance and behaviors, asking questions like:

- Does the patient appear injured or unwell?

- What is the mechanism of injury (MOI)?

- Is the patient alert and breathing?

- Are there signs of bleeding or shock?

This initial assessment guides your next steps. For instance, severe bleeding requires immediate intervention, such as controlling the bleeding with direct pressure or delegating that task to another responder.

While evaluating the patient, prioritize life-threatening conditions, such as confirming the patient’s level of consciousness, ensuring a clear airway, and checking for breathing and pulse. If the situation suggests potential spinal injuries, manual stabilization is necessary to prevent further harm.

Through these steps, responders can identify whether advanced medical help is needed and initiate the appropriate care.

Level of Consciousness

When approaching a patient, assessing their responsiveness is a key first step. You can gauge their level of consciousness (LOC) through verbal and physical cues, ranging from full awareness to complete unresponsiveness. Start by speaking calmly to the patient, introducing yourself, and assessing their understanding and responsiveness. Asking questions like “What happened?” or “Can you tell me your name?” helps you gauge how alert they are. Be aware that age, pre-existing conditions, and situational stress (e.g., trauma or fear) can influence their responses.

For children, consider their ability to understand or speak, and be patient. With older adults, cognitive conditions like dementia might affect their responses, so speaking to family members could clarify whether this is a normal behavior.

To classify their LOC, use the AVPU scale:

- Alert: Fully responsive to questions.

- Verbal: Responds only to verbal cues, such as your voice.

- Painful: Responds only to painful stimuli (e.g., pinching).

- Unresponsive: Does not respond to any stimuli.

Evaluating LOC is the first step in determining how to proceed with further assessments, such as airway, breathing, and circulation checks, which are essential to ensuring the patient’s well-being.

Airway Status

Airway is the clear pathway through which air moves from the nose and mouth to the lungs. In emergencies, ensuring that a patient’s airway remains open is critical, as they cannot breathe if it’s blocked. A conscious patient who can speak or cry has a functional airway, but even if they seem stable, there may still be risks like obstruction from trauma, swelling, or foreign objects.

Assessing Airway in a Responsive Patient: If the patient can speak, you know they have a clear airway.

Check for a stoma (a surgical opening in the neck) in patients who have had a laryngectomy or similar surgery. These patients may breathe through the stoma, so use a pediatric mask for ventilation.

Assessing an Airway in the Unconscious Patient: When a patient is unresponsive and lying face-up, the airway must be evaluated for any obstructions. If the patient is breathing normally (chest rising and falling), or responding verbally, make sure nothing is hindering airflow. Continue checking the patient’s breathing status as you care for them. Potential airway obstructions can come from fluids, debris, the tongue, or even swelling due to trauma or allergic reactions.

Opening the Mouth: If you need to open the mouth to clear debris or fluids in an unconscious patient, use the cross-finger technique:

- Kneel at the patient’s head.

- With gloved hands, place your thumb on the bottom teeth and your forefinger on the top teeth.

- Open the mouth with a scissor-like motion.

For an unconscious patient with no head or neck injuries, use the head-tilt/chin-lift maneuver:

- Kneel beside the patient.

- Place one hand on the forehead to tilt the head back.

- Lift the chin with two or three fingers to open the airway.

Be mindful not to tilt the head back too far in children and infants, as their airways are more sensitive.

View the following YouTube video to learn more: Airway manoeuvers (BLS) | Head-Tilt & Chin-Lift | Jaw Thrust | ABCDE Emergency | OSCE Guide | PLAB 2

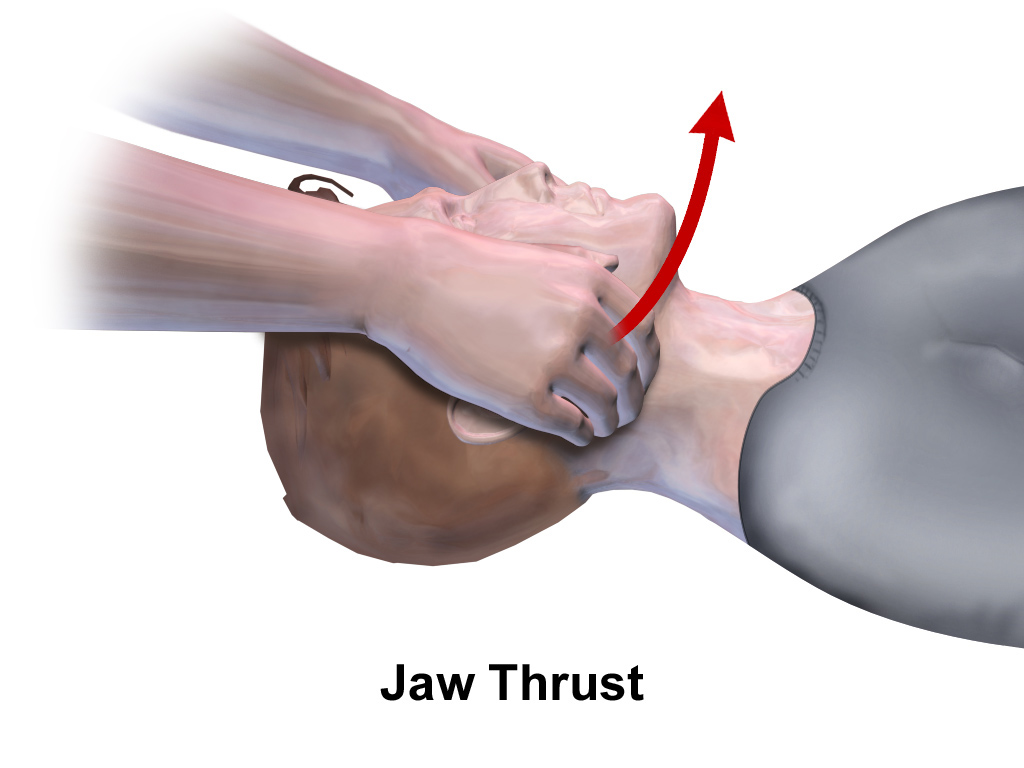

Jaw-Thrust Maneuver for Trauma Patients: If there is a suspicion of head, neck, or spine injury, the jaw-thrust (without head extension) maneuver should be used to open the airway:

- Position above the head and place your palms on the patient’s temples and your fingers under the angle of the jaw.

- Lift the jaw upward with your fingers, at least until the lower incisors are higher than the upper incisors.

Be sure to pull or push up only on the bony parts of the jaw. Pressure to the soft tissues of the neck may obstruct the airway. This technique helps move the tongue from blocking the throat while maintaining a neutral head and neck position.

Airway Maintenance: Assess whether any interventions are needed to keep the airway open. For example:

- Suction may be required to clear fluids.

- If a foreign object or debris is seen, a finger sweep may be necessary to remove it.

- An oral or nasal airway may be required if the tongue is blocking the throat.

If the patient wears dentures, leave them in place unless they obstruct the airway. Dentures can aid in securing a resuscitation mask, making ventilations easier.

Breathing Status

If a patient is breathing, you will notice chest rise and fall. Assess for breathing for 5-10 seconds. Be sure to also assess the pulse at the same time.

Assessing Breathing in a Responsive Patient: If the patient can speak, you know they have a clear airway.

Regularly assess the patient’s breathing, as it may change rapidly, requiring you to adjust your intervention.

Breathing Effort Observations: Observe if the patient uses accessory muscles (such as neck, chest, and abdominal muscles) or is experiencing nasal flaring in infants. A tripod position (sitting and leaning forward with arms braced) also suggests breathing difficulty. The arms are braced to give the muscles more support. Regular respirations are active on inhalation and passive on exhalation; or just allowing the chest to recoil. In respiratory distress, both inhalation and exhalation use active muscle movements.

Abnormal Breathing Patterns: In both adults and children, be alert to:

- Slow Breathing: Fewer than 8 breaths per minute for adults, fewer than 10 for children, or fewer than 20 for infants.

- Rapid Breathing: More than 20 breaths per minute for adults, 30 for children, or 60 for infants.

- Shallow Breathing: The chest barely rises with each breath.

- Noisy Breathing: Gurgling, wheezing, stridor, or snoring sounds.

Pediatric Considerations:

- Infants and children breathe faster than adults. For example, infants can breathe up to 50 breaths per minute.

- Look for signs of difficulty breathing, including shallow, deep, or irregular breaths.

- For children and infants, it’s especially important to monitor changes in their breathing patterns, as agonal (not effective, shallow, weak, gasping) breaths are rare in these age groups.

If the patient’s breathing is irregular or there is agonal breathing (a sign of cardiac arrest), provide care as if the patient is not breathing at all.

Providing Ventilations: If the patient is unable to breathe adequately:

- Supplemental oxygen may be necessary.

- In unresponsive patients, ensure their airway is open and assist with breathing using a bag-valve-mask (BVM) device.

- If the patient is hypoxic (low oxygen), they may show signs such as pale, cool skin.

- If the patient is cyanotic (blue lips or nail beds), they are likely not receiving enough oxygen.

Circulatory Status

When conducting a primary assessment, it’s essential to evaluate not only the airway and breathing but also the circulation of blood throughout the body. Without effective circulation, the heart’s ability to pump oxygen-rich blood is compromised, and severe complications can arise, including brain damage or death if untreated.

Pulse Assessment

A pulse is the result of blood being pushed through the arteries each time the heart beats. This pulse can be felt in arteries near the skin’s surface. When the heart is functioning normally, it beats in a regular rhythm, creating a pulse that can be felt in specific areas of the body. You are assessing for the strength, regularity, and rate of the pulse. The typical resting heart rate for an adult is between 60 and 100 beats per minute. However, athletes may have lower heart rates, sometimes even below 50 beats per minute (bradycardia), while a heart rate above 100 beats per minute (tachycardia) can indicate an abnormality, particularly at rest.

Example: A marathon runner, exhausted after a race, might present with a heart rate above the normal range due to exertion. On the other hand, if you encounter someone who is on beta-blockers for hypertension, their pulse may be unusually low but still normal for that individual.

In pediatrics, heart rates vary significantly with age. For example, a child aged 1-3 years may have a heart rate between 80 and 130 beats per minute, while a teenager may present with a heart rate between 60 and 105 beats per minute. These differences are natural and should be considered during assessment.

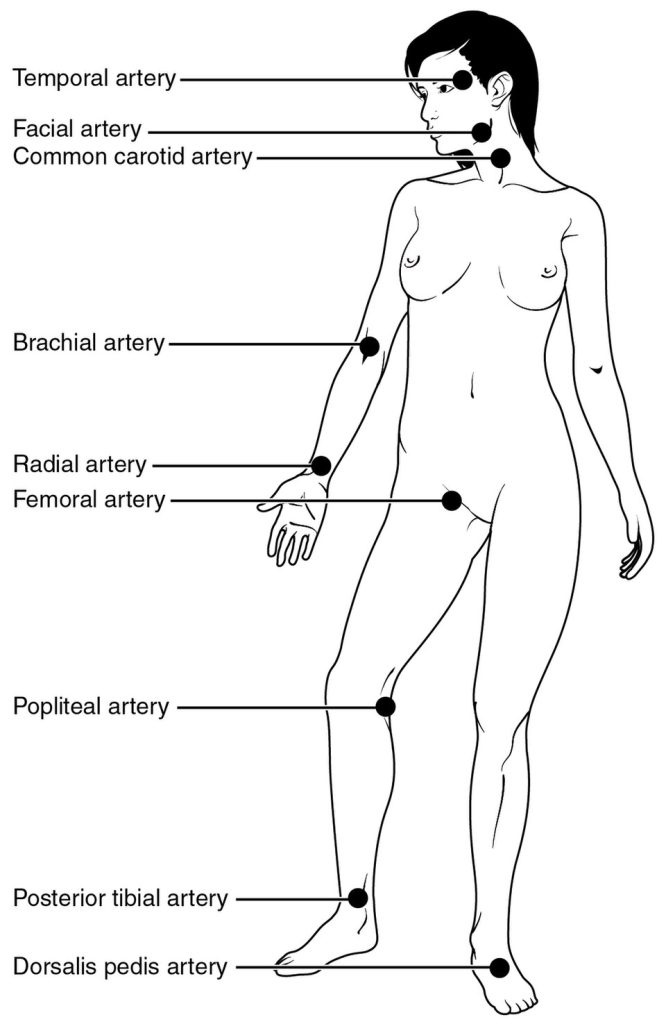

An irregular or absent pulse often signals a serious issue. The rate and rhythm of the pulse can change in response to factors like stress, pain, blood loss, or certain medical conditions. Recognize that the heart rate and the pulse rate may not be the same. The heart rate represents the electrical signals in the heart. The pulse rate is the impulse felt at peripheral artery points. When heart beats are not effective in moving blood forward, the beats may be non-perfusing, and the pulse rate will be less than the heart rate. This can happen when heart rates are too slow or too fast, or irregular. Make sure to clarify if you find a difference between a heart rate from auscultation (listening with a stethoscope) or recorded by a monitoring device, versus a palpable pulse at a certain location. The further away from the heart, the more force is required for a pulse. If you cannot feel a radial pulse, check the femoral or carotid sites.

Checking Pulse in Emergencies

To assess a pulse, use two fingers to press gently over a major artery near the skin’s surface. The most common pulse points are the carotid artery in the neck, the radial artery at the wrist, the femoral artery in the groin, and the brachial artery on the upper arm. To determine the pulse rate, count the number of beats in 15 seconds and multiply by 4, or count for 30 seconds and multiply by 2. Slower heart rates are more accurate with longer assessments. The best assessment is over a full minute, but is often not practical.

Example: If you’re unable to locate a pulse on one wrist, try the opposite wrist or the carotid artery in the neck. This strategy is useful when blood flow is obstructed, or the pulse is faint.

9 Pulse Points Assessment on the Body Nursing – Anatomy and Physiology

The nine pulse points on the body are important to learn as a healthcare professional. You’ll be using many of these common pulse points during your assessments, such as the head-to-toe assessment.

In this video, you’ll learn the locations and landmarks of nine different pulse points. In addition, you’ll learn information you’ll need to document while assessing the pulse point locations, including the pulse rhythm, strength, and pulse rate.

Here are the nine pulse points covered in this video:

- Temporal Pulse Point Assessment (temporal artery near ear and temples)

- Carotid Pulse Point Assessment (carotid artery on neck)

- Apical Pulse Point Assessment (apex of the heart)

- Brachial Pulse Point Assessment (brachial artery in arm)

- Radial Pulse Point Assessment (near the wrist and thumb)

- Femoral Pulse Point Assessment (near crease of upper leg)

- Popliteal Pulse Point Assessment (behind the knee)

- Dorsalis Pedis Pulse Point Assessment (top of foot)

- Posterior Tibial Pulse Point Assessment (inside of ankle region)

How to Check Your Pulse | Finding the Radial Pulse

How to check the radial pulse on a patient (clinical nursing skill). In addition, it shows how to find the radial pulse on your wrist, right below the thumb.

How to Find, Count, and Check a Carotid Pulse Rate

Checking the carotid pulse is a skill that you may use often. You may use this during a routine head-to-toe assessment, or various other situations in which you need to assess the patient’s pulse rate. The carotid artery is fairly easy to locate.

For an unconscious patient, focus on confirming whether the pulse is present rather than counting its rate or rhythm. In a life-threatening situation, where the pulse is absent, initiate CPR immediately.

Perfusion and Skin Assessment

After assessing the pulse, the next step is to evaluate perfusion, or whether blood is circulating adequately. The condition of the skin can provide important clues. During your evaluation, observe the following aspects of the skin:

- Color: Healthy, well-perfused skin is usually evenly colored, but a pale or bluish color can indicate poor circulation. Note that healthcare providers may have difficulty determining abnormal skin color when the patient has a different skin tone than their own. It is helpful to ask family or caregivers for noticeable changes. This is also useful in young children.

- Temperature: Warm skin suggests good blood flow, while cool skin may point to shock or hypothermia.

- Moisture: Wet or sweaty skin can be a sign of stress, pain, or shock, whereas dry skin typically indicates normal circulation.

- Capillary Refill: The time it takes for the color to return to the skin after pressure is applied is a quick indicator of blood flow. A slow refill may signal poor circulation.

Example: A patient suffering from shock may have pale, cool, and clammy skin, indicating that their blood is being diverted to vital organs, leaving less blood flow to peripheral areas.

Capillary Refill in Pediatric Patients

Capillary refill is an effective way to check circulation in children, especially in infants and toddlers. To perform this test, press on the child’s fingernail, toenail, forehead, or chest for 2 seconds and release. The color should return to the nailbed within 2 seconds. If it does not, this is a sign of inadequate circulation and may require urgent intervention.

Example: You might notice in a young child with a leg injury that the capillary refill time in the toes is prolonged, which could suggest that circulation to the lower extremities is compromised.

View the following YouTube video on capillary refill:

Identifying Life-Threatening Conditions

During the assessment of the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation, it’s crucial to identify any immediate threats to life. This includes any abnormal pulse, changes in skin color, or difficulty with perfusion. For instance, if a patient shows signs of shock, such as pale, cold skin and weak pulses, this requires immediate action. For unstable patients, reassess vital signs every 5 minutes or more frequently if conditions worsen.

Ultimately, your role as an EMR is to quickly identify these signs, provide necessary interventions like CPR or bleeding control, and ensure that the patient remains stable until more advanced care is available.

9.4 History Taking

You are the EMR

You arrive at the scene of a house fire that has been mostly extinguished. Firefighters are still working to ventilate the structure. A woman is standing in the front yard, coughing and holding her chest. She reports that she was inside when the fire started and was unable to escape until firefighters arrived. As an EMR, how would you assess this woman, and what steps would you take to ensure her safety and well-being?

Obtaining a Focused Medical History

As an EMR, one of your primary responsibilities is to gather as much relevant information as possible about the situation, allowing you to communicate critical details to more advanced medical professionals. While direct observation of the scene and patient is essential, engaging in interviews with those involved or bystanders is often your most valuable source of information. However, always ensure your safety before entering the scene.

This process of gathering information, particularly about the incident and the patient’s medical history, is referred to as obtaining a focused history. It should be a quick and efficient part of your assessment, typically completed before or during the physical exam. When responding to critically injured patients or unconscious medical cases, you may need to prioritize physical assessment before the history taking.

Key Considerations When Taking a History

- Older Adults: When interacting with elderly patients, approach them with respect and formality, using titles like “Mr.” or “Mrs.” Position yourself at eye level and speak slowly, as older adults may experience hearing or vision impairments. Additionally, confusion in older patients can be due to acute medical issues or conditions like dementia, so be patient and give them time to respond. You may also encounter medical identification tags, service animals, or medications that provide important information about their condition. If you’re in a patient’s home, be on the lookout for a Vial of Life label, which will help you access vital health details.

- Pediatric Considerations: Children and infants may not respond verbally or immediately to your questions due to fear, confusion, or a lack of understanding. Always try to approach them at their eye level and reassure them. Keep parents or guardians nearby, unless it’s absolutely necessary to separate them.

- Inability to Obtain Information From the Patient: Sometimes, you may be unable to gather information directly from the patient, especially if they are unconscious, agitated, or confused. In these cases, you can turn to family members, caregivers, or bystanders for insights into the patient’s condition. If the patient doesn’t speak your language, seek help from others who can interpret or translate.

- Chief Complaint: The chief complaint refers to the main reason EMS was called to the scene. It’s essential to ask the patient, “What made you call 911?” or “What seems to be the problem?” Record the complaint in the patient’s own words. Sometimes, the primary issue you observe (e.g., a visible injury) may not be the most urgent problem, so be thorough in assessing the situation.

- Mechanism of Injury (MOI) or Nature of Illness (NOI): Knowing the MOI for trauma cases or NOI for medical cases is crucial. This helps you anticipate potential injuries or medical conditions that need immediate attention. For instance, a car accident might lead you to suspect internal injuries or spinal trauma, while a patient experiencing chest pain might be suffering from a cardiac event. If the MOI suggests the potential for spinal injury, ensure the patient remains immobilized until further medical support is available.

- Pain Assessment: Assessing pain is an essential part of obtaining a history. Ask the patient to describe the pain’s location, intensity, and nature (e.g., sharp, dull, throbbing). Use the OPQRST method to help clarify the onset, provocation, quality, radiation, severity, and timing of the pain. For example, ask: “When did the pain start?” or “Does the pain radiate to any other part of your body?” If the patient is unable to speak, other clues, such as facial expressions or body language, may provide insights.

The SAMPLE History

Use the SAMPLE mnemonic to gather important information:

- Signs and Symptoms: Observe the patient’s condition and ask about any symptoms they may be experiencing.

- Allergies: Check if the patient has any known allergies, especially to medications or environmental triggers.

- Medications: Ask about any current medications the patient is taking, including over-the-counter drugs or supplements.

- Pertinent Medical History: Gather information on past medical conditions that could be relevant to the current situation.

- Last Oral Intake: Determine when and what the patient last ate or drank, as this could affect treatment (e.g., for potential surgery).

- Events Leading Up to the Incident: Find out what happened just before the emergency, as it could provide vital clues to the cause of the illness or injury.

OPQRST

Use the OPQRST mnemonic to define the symptom, especially pain:

- Onset: When did the pain start? What were you doing? Did it start all of a sudden, or gradually build up?

- Provocation/Palliation: What makes the pain worse or better?

- Quality: What does the pain feel like (sharp, dull, etc.)?

- Region/Radiation: Where is the pain located, and does it spread? Point to where is hurts, and where it goes.

- Severity: On a scale of 1 to 10, how bad is the pain? (Remember this number is very subjective.)

- Time: How long has the pain been present?

Signs and Symptoms

When assessing a patient, it is crucial to differentiate between signs and symptoms. Signs are objective indicators that you, as the responder, can observe or measure during your assessment. These might include observable physical injuries, such as a visible wound, bruising, or swelling. For example, you might notice a deep laceration on a patient’s arm after a car accident or detect the sound of wheezing when a patient is experiencing respiratory distress. On the other hand, symptoms are subjective, meaning they are reported by the patient based on their personal experience. For instance, a patient may describe feeling lightheaded, report chest pain, or express difficulty breathing. When gathering symptoms, ask the patient to elaborate on their condition. Some good questions to ask include:

- “Can you point to where you are feeling pain?”

- “How severe is the pain on a scale from 1 to 10?”

- “Have you noticed any dizziness or shortness of breath?”

- “How severe is your shortness of breath on a scale from 1 to 10?”

- “Do you feel nauseated or have an upset stomach?”

- “What other changes have you noticed?”

These open-ended questions will help you obtain a clearer picture of the patient’s condition, allowing for more effective communication with other healthcare professionals.

Allergies

Inquiring about allergies is a vital step in assessing a patient’s medical history. Ask the patient whether they have any known allergies, particularly to medications, food, or environmental factors. For example, a patient might inform you that they have a severe allergy to penicillin, which could be critical if they need antibiotics. You should also ask:

- “Do you have any allergies to food, medications, or environmental triggers?”

- “Have you had an allergic reaction to any medications in the past?”

- “Do you carry an EpiPen or other allergy medications with you?”

Being aware of allergies ensures that you do not inadvertently administer something harmful, such as an inappropriate medication, and it also helps with faster and safer decision-making on the scene.

Medications

Patients may be taking prescribed medications, over-the-counter drugs, vitamins, or even herbal remedies, all of which can influence their current condition or treatment options. It’s essential to ask the patient about their medication history. For example, you might ask if they are currently using any prescription drugs, such as blood thinners or antihypertensives, which could be important for assessing risks related to bleeding or blood pressure. Other questions to consider include:

- “Do you take any medications, either prescription or over-the-counter?”

- “Are you currently using any patches or inhalers?”

- “Have you ever taken someone else’s medication, even by accident?”

- “Do you take any vitamins or natural supplements regularly?”

- “Do you take, or has anyone given you, any street drugs?”

These details are crucial in forming an accurate understanding of the patient’s medical status, as some medications can affect responses to injuries or illnesses.

Pertinent Medical History

Understanding the patient’s medical background is essential for providing effective care. Ask whether the patient has any pre-existing health conditions, such as diabetes, asthma, or heart disease, as these conditions may affect the treatment you administer. Additionally, knowing if the patient has experienced similar symptoms in the past, or if they’ve recently been hospitalized or had surgery, can provide vital clues to their current state. For example, a patient with a history of heart disease who complains of chest pain may be at higher risk for a cardiac event. You should also ask if there are any other health conditions that you should be aware of, such as:

- “Have you ever had this happen before?”

- “Do you have a history of heart disease, asthma, or diabetes?”

- “Have you recently had surgery or been hospitalized for any reason?”

- “Could you be pregnant?”

This information will guide your treatment decisions and assist you in providing the most appropriate care, particularly in complex situations where the patient’s past medical history plays a critical role.

Last Oral Intake

Knowing when the patient last ate or drank and what they consumed can be important, especially if the patient requires surgery or other interventions that may be affected by food or fluid intake. For instance, if a patient has eaten a large meal shortly before a traumatic injury, they may be at higher risk for aspiration if they need to be intubated. Likewise, knowing what medications they’ve taken recently is important for avoiding potential interactions or adverse effects. Ask:

- “When did you last eat or drink something?”

- “What did you have to eat or drink?”

- “Is that what you normally eat or drink?”

Understanding these factors is important for making decisions related to treatment, especially if you anticipate needing to administer anesthesia or other medications.

Events Leading Up to the Incident

The events leading up to the incident provide context that can help you determine the MOI for trauma patients or understand the NOI for medical patients. Understanding what the patient was doing immediately before the event can offer insight into the cause and severity of the condition. For example, if a patient was involved in a high-speed collision, you might suspect traumatic injuries, such as fractures or internal bleeding. If the patient suddenly collapsed while exerting themselves, it might indicate a cardiac event or stroke. Questions to ask in this section include:

- “What were you doing right before the incident happened?”

- “Did you experience any dizziness, chest pain, or shortness of breath?”

- “Were you participating in any physical activity when this occurred?”

By gathering this information, you can form a more complete picture of the patient’s situation, guiding you in providing the appropriate care and helping other medical personnel understand the underlying causes of the emergency.

Pain and Trauma Considerations

When assessing trauma patients, understanding how the injury occurred is vital. It helps predict possible internal injuries or complications, especially when dealing with significant MOIs like motor vehicle collisions, falls from height, or blunt trauma. In these situations, make sure to immobilize the patient and take appropriate precautions, such as applying cervical collars if necessary.

Using Bystanders and Family for Information

Not all necessary information comes directly from the patient. If the patient is unresponsive or confused, family members, friends, or bystanders may be able to provide insight into the situation. They might also help calm the patient or even assist in providing a clearer medical history. Ask questions like:

- “Has the patient had any prior heart conditions?”

- “What medications are they currently on?”

Gathering Information in Challenging Situations

In some cases, such as when the patient is a child or has lost consciousness, you may have to rely on family members, friends, or witnesses to provide the history. Always make sure to obtain consent before touching the patient, and be prepared to deal with the emotional state of those around you, especially in critical situations.

By carefully conducting a thorough history taking, you not only assist in making an accurate diagnosis but also prepare the patient for higher-level care. Your ability to gather and communicate this information efficiently can significantly affect the outcome of the situation.

9.5 Secondary Assessment

The secondary assessment is a critical step in evaluating a patient’s condition after addressing any immediate life-threatening issues identified during the primary assessment. It allows responders to gather detailed information about injuries or medical conditions that could worsen without proper care. This assessment typically involves a head-to-toe physical exam but may include a focused exam, depending on the patient’s presentation. The secondary assessment involves additional equipment to obtain vital signs, listen to lung sounds, or check pupil reactivity.

Key Considerations During Secondary Assessment

If a patient presents with serious injuries or altered mental status, the first priority is to stabilize life-threatening conditions. This includes unconsciousness, severe bleeding, or failure to maintain an airway. Only after addressing these conditions should you proceed with the secondary assessment, which may involve a more thorough evaluation of the patient’s physical condition.

For example, in cases of severe trauma, where spinal injuries are suspected, maintaining spinal motion restriction and ensuring an open airway should be the top priorities. In cases like these, rapid intervention and transportation may be necessary to prevent further harm.

Steps for Conducting the Secondary Assessment

- Physical Exam:

- Trauma: Rapid Head-to-Toe Exam

- Start by inspecting the head and neck for visible signs of injury. Look for swelling, bruising, deformities, or any other abnormal findings. Proceed to the chest, checking for signs of broken ribs, or decreased lung sounds. Palpate the abdomen to assess for tenderness, and be cautious around areas the patient reports as painful, such as the upper right quadrant, where liver injuries are often detected. Confirm circulation, motor movement, and sensation in all extremities.

- The less responsive your patient is, the more you must rely on palpating all areas. If they are alert, they can quickly confirm or deny pain or injury.

- Medical: Assess Body Part/System

- Cardiovascular, Pulmonary, Neurological, Musculoskeletal, Integumentary, GI/GU, Reproductive, Psychological/Social

- Again, the less responsive your patient is, the more you must rely on your examination.

- Trauma: Rapid Head-to-Toe Exam

- Assess Baseline Vital Signs: Measure the patient’s blood pressure, pulse, respiratory rate, and oxygen saturation levels. These readings give you a snapshot of the patient’s condition, such as signs of shock or breathing difficulties.

- Reevaluate Mental Status: Always reassess the patient’s mental status, especially if they were initially altered or confused. A change in mental status could indicate worsening conditions, such as increased intracranial pressure or hypoxia.

- Prepare for Transport: Throughout the secondary assessment, make preparations for transport. Ensure that the ambulance or other transport resources are ready, and alert the receiving facility about the patient’s status and needs.

- Provide Emergency Care: As you gather more information, continue providing care for the patient. For example, if you discover signs of a puncture wound in the chest, you may need to apply an occlusive dressing to prevent air from entering the wound.

View the following YouTube video for more information: Secondary Survey

DCAP-BTLS and DOTS Mnemonics

When conducting a trauma exam, the mnemonics DCAP-BTLS and DOTS are invaluable in identifying the types of injuries to look for:

- DCAP-BTLS: Deformities, Contusions, Abrasions, Punctures/Penetrations, Burns, Tenderness, Lacerations, and Swelling.

- DOTS: Deformities, Open injuries, Tenderness, and Swelling.

For example, if you encounter a patient with a possible pelvic injury from a fall, you’ll look for any deformities in the pelvic region, swelling, or tenderness upon palpation.

Special Considerations

- Unresponsive Patients: If you’re assessing an unresponsive patient, start with a rapid head-to-toe assessment. This helps to identify any immediately life-threatening injuries or conditions. In these cases, time is critical, and the focus should be on maintaining an airway, managing circulation, and preparing for transport as soon as possible.

- Privacy and Dignity: Always ensure the patient’s privacy during the physical exam. Expose only the areas necessary for examination, especially in the case of serious MOI, and cover the rest of the body with a sheet to maintain dignity.

Obtaining Vital Signs

Obtaining vital signs during the secondary assessment is essential when evaluating both medical and trauma patients. Vital signs (including pulse, respirations, blood pressure, skin condition/temperature, and oxygen saturation) provide critical insight into a patient’s physiological status and can reveal early signs of deterioration. For trauma patients, vital signs help identify internal bleeding, shock, or rising intracranial pressure, even when external injuries are not obvious. In medical patients, abnormal vital signs can point to conditions such as infection, cardiac events, respiratory distress, or metabolic imbalances. Consistent and accurate vital sign monitoring supports clinical decision-making, helps determine transport urgency, and provides a baseline for comparison as patient care progresses.

As assessment of pulse and respirations have been previously described, this section will focus on methods to measure blood pressure.

Obtaining a Blood Pressure Reading

Following source: 15.7 Blood Pressure – Clinical Nursing Skills | OpenStax

Blood pressure is the pressure exerted by the blood on arterial walls and must be measured to ensure the pressure is adequate to perfuse the body and not too great to rupture the blood vessels. It consists of two numbers, a higher systolic and lower diastolic, and is reported as a fraction with the systolic on top and the diastolic on the bottom. Systole is the pressure of blood during contraction of the left ventricle. Diastole is the pressure of the blood when the ventricles are at rest and filling.

Variations in Blood Pressure

The normal adult blood pressure ranges between 90 to 120 systolic and 60 to 80 diastolic, but it can vary due to medical conditions and age. An elevated blood pressure is known as hypertension and a lowered one is called hypotension. Either of these conditions can lead to serious health consequences. Hypertension increases the pressure placed on the arterial walls leading to complications such as hemorrhagic stroke but also increases the risk of a myriad of health conditions if it occurs with other comorbidities, particularly myocardial infarction, heart failure, cerebrovascular accident, and end-stage renal disease. Hypotension also presents various dangers. Hypotension means that blood is not being circulated sufficiently, which can lead to ischemia, anoxic brain injury, and even death. Hypotension is a hallmark characteristic of shock, a life-threatening condition that develops from multiple medical causes.

| Category | Blood Pressure Reading |

|---|---|

| Normal | 90 to 119/60 to 80 |

| Elevated | 120 to 129 systolic and ≤80 diastolic |

| Stage I hypertension | 130 to 139 systolic or 80 to 89 diastolic |

| Stage II hypertension | ≥140 systolic or ≥90 diastolic |

Blood Pressure Cuff and Size

Blood pressure cuffs are available in a variety of sizes and are meant to wrap around the upper arm. The nurse is responsible for obtaining a proper size cuff for the patient (Figure 15.26). Within the cuff is the inflatable bladder, which, when inflated, impedes the blood flow through the brachial artery. The edges of the cuff will encircle the upper arm and be secured with Velcro to ensure that the cuff does not pop off during inflation of the bladder.

The first step is selecting which arm to use, this can be patient preference or the need to avoid the arm with IVs, lymphedema, fistulas, and so on. The width of the cuff should cover approximately 80 percent of the upper arm from shoulder to elbow, and the bladder within the cuff should encircle about 40 percent of the arm. An improper blood pressure cuff size leads to an inaccurate reading. If a blood pressure cuff is too large, the reading will be lower. If it is too small, the reading will be higher. At times, hypertension has been missed by medical personnel simply due to improper equipment.

Pediatric Considerations

Pediatric blood pressure cuff sizes are limited in EMS. The equipment is often not available for children under the age of 10 years, and mostly for those under 5 years old. A small, child, or infant BP cuff may be used. The internal bladder of the cuff must not overlap when applied. Patient movement is a common source of error in BP measurements.

Technique for the Manual Blood Pressure Measurement

The preferred technique is to estimate the systolic BP by the palpation method, and then apply the auscultation method.

- Choose the appropriate BP cuff

- Palpate the radial or brachial artery pulse

- Inflate the BP cuff until loss of pulse

- Note level

- Apply stethoscope with diaphragm (wider, covered side) over the brachial artery point

- https://www.bing.com/ck/a?!&&p=c1310e898ca4dd1e2cf036a1812a1786a5b838ddd65eb41cdf9e6d8a5e62e512JmltdHM9MTc2MTk1NTIwMA&ptn=3&ver=2&hsh=4&fclid=145eadd3-def0-653c-17ee-bb5edf9f6414&u=a1L2ltYWdlcy9zZWFyY2g_cT1kaWFwaHJhZ20rb3IrYmVsbCtzaWRlK29mK3N0ZXRob3Njb3BlJmlkPUVBNDNBMDQ5MkRBQUUwRTUyRTk0Qjg4QkUyRDU3QjcwRjg3OTJBRjA

- Inflate the cuff to 20 mmHg above the estimated systolic pressure

- Release the air at a rate of 2 to 3 mmHg per second while listening through your stethoscope.

- First Korotkoff sound (systolic pressure):

- As the pressure in the cuff is released, listen for the first pulse sound, known as the first Korotkoff sound. The reading at the time of hearing the first Korotkoff sound is known as the systolic pressure.

- Disappearance of the Korotkoff sound (diastolic pressure):

- Continue to slowly release the pressure at a rate of 2 to 3 mmHg per second, as you continue to listen with your stethoscope. The point at which the sound stops indicates the level of the diastolic blood pressure.

Korotkoff Sounds

To place the cuff, align the cuff with the artery position indicator label on the cuff. The valve of the inflation bulb should be fully closed. Place the diaphragm of the stethoscope over the brachial artery and inflate the cuff by squeezing the bulb. The gauge will show the pressure as the cuff inflates. Slowly deflate the bladder while carefully listening for the return of the pulse. This is done by turning the knob on the valve counterclockwise approximately 2 mm/s while listening and watching the pressure indicated on the gauge. The pulsating, tapping sound heard with a stethoscope as blood flows through the brachial artery is known as a Korotkoff sound. The first Korotkoff sound is the systolic blood pressure reading, and the last Korotkoff sound is the diastolic reading. Once the diastolic number is obtained and there are no more Korotkoff sounds heard, the bladder can be quickly deflated and the cuff removed. Remember that if the blood pressure does not align with the patient’s previous trends, the nurse should recheck in the other arm, recheck with a manual cuff if the reading was taken using an electronic machine, or let the patient rest for five minutes and recheck.

Link to Learning

A demonstration of what to listen for when listening for the Korotkoff sounds is presented in this video.

Blood Pressure Measurement: How to Check Blood Pressure Manually

Blood pressure measurement technique: nurse demonstrates how to check a blood pressure manually at home with a blood pressure cuff kit (sphygmomanometer) and stethoscope.

Factors Affecting Blood Pressure

Blood pressure is determined by the force of heart contractions, the diameter of the blood vessels, and the amount of circulating blood. If any of these factors are abnormal, blood pressure will be abnormal.

The force of heart contractions will determine the force that blood exerts on the arterial walls. During exercise, the heart will strongly contract, increasing the blood pressure temporarily during the activity. When the heart contractions are weak, blood pressure drops. If the heart is unable to contract and pump blood through the vasculature, it is known as cardiogenic shock. A primary cause of this is heart failure.

Need to find an EMS equivalent video, this is more detailed than needed.

Vital Signs Nursing: Respiratory Rate, Pulse, Blood Pressure, Temperature, Pain, Oxygen

Vital signs help us assess patients in the nursing profession, and there are six common vital signs that we assess as nurses:

1. Heart Rate (Pulse)

2. Respiration Rate

3. Temperature (often not possible for non-transporting EMS staff)

4. Blood Pressure

5. Pain Rating

6. Oxygen Saturation

This video will demonstrate how to check vital signs (live) on a patient, along with normal rates for each assessment.

Palpated Blood Pressure Measurement

When an auscultated (using a stethoscope) blood pressure reading is not possible due to environmental noise or patient movement, the systolic measurement may be obtained via palpation.

- Apply the BP cuff to the upper arm

- Palpate the radial artery pulse

- Inflate the BP cuff until the pulse disappears

- Slowly release the BP cuff pressure

- Note the return of the radial pulse as the systolic blood pressure measurement

- Record the reading as XXX/P

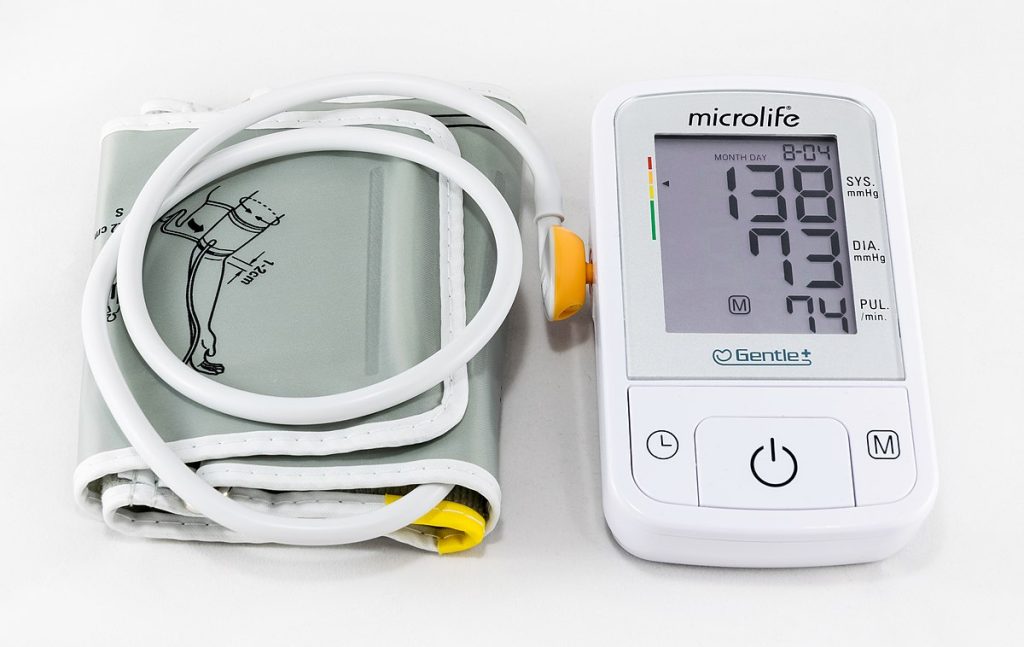

Automated Blood Pressure Measurements

The convenience of an automated blood pressure measurement must be weighed by its accuracy. Patient movement, incorrect cuff size, and hypotension limit the ability of a monitor or automated BP cuff. When an automated BP cuff fails or “times out,” a manual measurement should be obtained. When the automated BP measurement is significantly different, a manual BP should be obtained. A blood pressure change of more than 30 mmHg or 33% (1/3) should be rechecked.

The Detailed Physical Exam

After completing the focused or rapid assessment, if the patient’s condition allows, a more detailed physical exam may be necessary. This is especially the case when there’s time available or when the patient is en route to the hospital.

For example, while treating a patient with a suspected fractured arm, you might find that the arm is swollen, bruised, and tender to the touch. The secondary exam would allow you to assess the range of motion, check for pulses, and evaluate nerve function to gauge the extent of injury.

The detailed exam should be systematic, starting from the head and moving down to the feet. Use your senses to inspect, palpate, and auscultate (listen). For example, listening for abnormal breath sounds in the chest could reveal conditions such as pneumonia or pneumothorax. As you examine the patient, ask them to describe any areas of discomfort or pain, and watch for any signs of distress, such as grimacing or shallow breathing.

Conclusion

The secondary assessment is a systematic approach to identifying non-life-threatening injuries or medical conditions. It helps ensure that all potential issues are identified, and proper care is provided. By following a structured process—gathering a SAMPLE history, performing a thorough physical exam, assessing vital signs, and considering the need for additional resources—you’ll be well-equipped to address the patient’s needs and prepare them for transport to the appropriate facility.

9.6 Monitoring Devices

For EMRs, understanding and properly using medical devices is essential for providing effective care. While this equipment is important for gathering data about the patient’s condition, it’s crucial to remember that the true focus should always be on the patient. Your hands, eyes, and judgment are your most valuable tools when assessing a patient. Here’s an overview of some key devices you’ll likely use and why it’s important to integrate them with hands-on patient care.

1. Stethoscope

A stethoscope is essential for listening to internal sounds, such as the heart, lungs, and abdomen. It helps in assessing heart rate, lung sounds, and the presence of abnormal noises such as wheezing, crackles, or gurgling. While the stethoscope is an important diagnostic tool, it’s essential to remember that listening is just one part of your assessment. Feel for pulses and observe the patient’s overall appearance—this can give you insights that a stethoscope alone cannot.

- Use it: To assess lung sounds, heart sounds, and bowel sounds.

- Remember: Always be sure to listen actively and in combination with physical assessments. Don’t rely only on the stethoscope. Your observations and physical touch are equally important.

2. Sphygmomanometer (Blood Pressure Cuff)

The sphygmomanometer is used to measure blood pressure and provides critical information about a patient’s cardiovascular status. It includes a cuff, a pressure gauge, and a bulb for inflating the cuff. Accurate blood pressure measurement helps identify conditions such as hypertension or hypotension.

- Use it: To assess the blood pressure by inflating the cuff and listening for the Korotkoff sounds using a stethoscope.

- Remember: Blood pressure is only one piece of the puzzle. Be sure to assess the patient’s overall condition and not just their blood pressure. A patient’s history, mental state, and physical appearance provide important context.

3. Blood Glucose Monitor

A blood glucose monitor is an optional skill or piece of equipment for the EMR. It is used to measure the amount of glucose (sugar) in a patient’s blood. This is especially useful for patients who may be experiencing diabetic emergencies such as hypoglycemia or hyperglycemia.

- Use it: To quickly assess blood sugar levels, especially if the patient is showing signs of confusion, dizziness, or altered mental status.

- Remember: The blood glucose level is helpful, but it’s just one part of the clinical picture. Always look at the patient’s behavior, symptoms, and history. A blood glucose reading without considering the patient’s overall condition might lead you to miss a more urgent problem.

Blood Glucose Monitoring

Skills-Procedures-Manual-August-11-2021.pdf

- Objective(s): Provide systematic approach to accurately document patient blood glucose levels to rule in or rule out treatable diabetic related emergencies

- Equipment Needed

- Adhesive bandage

- 2X2s

- Sterilizing wipes

- Lancets

- Glucometer with test strips

- Sharps container

- Steps in Skill/Assessment

- Ensure glucometer is appropriately calibrated according to manufacture instructions

- Assemble required equipment

- Prepare glucometer to accept sample

- Appropriately clean patient’s finger and allow to air dry

- Using lancet, prick side of patient’s finger and place lancet in approved sharps container

- Bring glucometer to finger and collect appropriate sample

- Agency or manufacturer policy may indicate to wipe off the first drop of blood and use the second drop

- Properly document glucometer reading

- Critical Criteria

- Ensure proper management of sharps

- Precautions/Comments

- Record reading in mg/dL

- Consider use on all patients with altered level of consciousness

- Ensure unit is calibrated per manufacturers specifications

- Check expiration date on test strips

EMS Skills – Blood Glucose Measurement

YouTube WCTCFire&EMS

https://www.bing.com/videos/riverview/relatedvideo?q=Waukesha+County+Technical+college+EMS+videos+AND+blood+glucose+&refig=69092675c0d94c7fb14b0e764e77251b&pc=LCTS&ru=%2fsearch%3fq%3dWaukesha%2bCounty%2bTechnical%2bcollege%2bEMS%2bvideos%2bAND%2bblood%2bglucose%2b%26form%3dANNTH1%26refig%3d69092675c0d94c7fb14b0e764e77251b%26pc%3dLCTS&mmscn=vwrc&mid=60F3D1A5D6A10CE034DC60F3D1A5D6A10CE034DC&FORM=WRVORC&ntb=1&msockid=c34225b8b90211f082a291bdbef236f5

4. Oximeter

An oximeter is a non-invasive monitoring technique that measures the oxygen saturation in the blood by shining light at specific wavelengths through tissue, most commonly the fingernail bed. Deoxygenated and oxygenated hemoglobin absorb light at different wavelengths. The absorbed light is processed by an algorithm in the pulse oximeter to display a saturation value. This is particularly useful in respiratory emergencies, such as asthma attacks, pneumonia, or overdose situations.

While easy to use, the pulse oximeter has multiple limitations. Any decrease in perfusion to the tissue under the oximeter may give a false reading. This may occur in hypotension, peripheral vascular disease, irregular or abnormal heart rhythms, or injuries to the area. This happens frequently when a blood pressure reading is taken on the same extremity where the oximeter is placed. Another factor is interference with the passage of light into the underlying tissues. There are various reported errors due to dark nail polish or artificial nails. Too much overhead light may interfere with the reading, requiring a towel or blanket to be placed over the device. Chemicals or medications in the blood may change the light absorption. Critically for EMS, exposure to carbon monoxide will change the hemoglobin and cause a falsely elevated saturation reading in standard pulse oximeters.

- Use it: To monitor oxygen levels, especially when the patient is showing signs of respiratory distress.

- Remember: While an oximeter provides important data, it doesn’t replace your assessment of the patient’s breathing and overall condition. For example, a low oxygen reading might not be accurate if the patient is moving or has poor circulation.

5. Automatic Blood Pressure Device

An automatic blood pressure cuff is a more modern device that inflates and deflates automatically and provides a digital reading of the blood pressure. These devices are useful in situations where quick readings are necessary and you need both hands free to monitor the patient.

- Use it: To obtain blood pressure readings quickly when you are managing other aspects of the patient’s care.

- Remember: Like with the sphygmomanometer, don’t just focus on the number. The context in which the reading is taken matters. A high reading might be less concerning in an anxious patient than in one who is calm and stable.

The Importance of Patient Interaction and Hands-On Assessment

Although medical devices play a vital role in emergency care, the most important part of patient assessment is the human connection—your ability to observe, touch, and interact with the patient directly.

- Use Your Hands: Palpation (feeling) is a crucial part of assessment. For example, feeling for a pulse, determining areas of tenderness, or assessing for swelling can provide key information about the patient’s condition. Never underestimate the importance of physically assessing the patient’s body, as sometimes things you feel will tell you more than any device.

- Observe Closely: The patient’s appearance, behavior, and responses provide vital clues to their condition. Is the patient alert and oriented, or are they disoriented or unresponsive? Are they in visible distress, or do they appear calm? These are things that a device cannot tell you but can be invaluable for making clinical decisions.

- Look Beyond the Equipment: Equipment is a tool for you to use, but it should never replace the need for a full, hands-on assessment. When using equipment like an oximeter or sphygmomanometer, keep your eyes on the patient. If their oxygen levels are low, is their breathing labored? If their blood pressure is low, are they showing signs of shock? Always use the equipment in conjunction with your assessment skills.

- Communication is Key: Always explain what you’re doing. For example, when you’re taking vitals, let the patient know why it’s important and how it helps you assess their condition. This communication can help keep them calm, especially in stressful situations.

While equipment is necessary for gathering data, remember that your greatest diagnostic tool is your own ability to assess, interact, and care for the patient. The stethoscope, sphygmomanometer, blood glucose monitor, oximeter, and automatic blood pressure devices are all helpful, but they should always complement your direct physical assessments. Always look at your patient holistically and never rely solely on the devices in front of you. By combining technology with hands-on care, you can ensure the best possible outcome for your patient.

Reassessment

Once you’ve completed the secondary assessment and addressed any immediate injuries or illnesses, the next step is to continuously reassess the patient as you wait for advanced medical personnel to arrive. Ongoing assessment helps to identify any changes in the patient’s condition promptly, ensuring that you can modify your care accordingly. It also allows you to monitor the effectiveness of the interventions you’ve already provided. Keep detailed notes on any changes in the patient’s condition to relay to the next healthcare provider when they take over.

A patient’s status can change quickly; conditions that initially seem stable can deteriorate, or a sudden, life-threatening issue like respiratory or cardiac arrest can arise unexpectedly. Do not assume the patient is safe just because they appeared stable at first. Reassessing regularly ensures you don’t miss any developing complications.

For patients in critical condition, reassess at least every 5 minutes, or more frequently if necessary based on their condition. For more stable patients, reassess every 15 minutes, or as needed, depending on their circumstances. While repeating the primary assessment isn’t always necessary, you should check for any changes, especially if a new issue arises.

Your reassessment includes:

- Primary Assessment: Continuously verify that the patient’s airway remains clear, that they’re breathing adequately, and that their circulation is stable.

- Vital Signs: Ensure vital signs remain consistent or track any concerning fluctuations.

- Chief Complaint: Keep a close watch on the reason the patient called for help and monitor for any progression of symptoms.

- Interventions: Reevaluate the effectiveness of the care you’ve already provided, and be prepared to adjust or add new interventions as needed.

Reassessing the Primary Assessment

In each reassessment, it’s important to return to the basics. Review the patient’s airway, breathing, and circulation, and compare these findings to your initial assessment. For instance, assess the patient’s level of consciousness. Are they becoming more alert, or are they deteriorating into confusion or unresponsiveness? Ensure the airway remains open, and check the adequacy of breathing by counting the rate, depth, and effort. Listen to breath sounds to detect any changes that might indicate worsening respiratory distress.

Next, check pulses to assess circulation and confirm whether both the carotid and radial pulses are still strong. Observe the patient’s skin—are they still warm, dry, and pink, or has the appearance changed, indicating shock or a deterioration in circulation?

Ongoing Monitoring

A patient’s condition can evolve, and it’s crucial to stay vigilant. Even if the primary and secondary assessments don’t initially reveal significant concerns, you must continue reassessing frequently, especially in the dynamic environment of emergency care. For example, you might find that a patient initially stable during the primary assessment begins to experience shortness of breath or chest pain during transport. At this point, you should call for additional help and adjust your care, potentially administering oxygen or altering your positioning to support the patient’s condition.

Adjusting Care Based on Reassessment

As you evaluate the effectiveness of your interventions, consider whether the care you’ve provided has made a noticeable difference. Are the patient’s vital signs improving, or have new problems emerged that need immediate attention? Sometimes, you might need to introduce a new intervention, such as pain management, or modify your current approach if things are not improving as expected.

In every situation, trust your instincts and keep reassessing. Each patient presents unique circumstances, and conditions may change unexpectedly. While you don’t need to diagnose the exact cause of a patient’s symptoms, focusing on life-threatening conditions and treating them first should always guide your care. By continually reassessing and adjusting, you can ensure that the patient receives the most appropriate care possible until more advanced medical personnel take over.

9.7 Case Study: Mrs. Martha Smith—Elderly Adult with Hypoglycemia

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ An elderly woman is sitting along on a sofa. She appears tired.](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/68/2025/04/d0cibq4r2pig0081cd80-701x1024.jpg)

Background:

Mrs. Martha Smith is a 76-year-old female who was found disoriented in her home by her daughter. Her daughter reports that she hasn’t eaten much today and has been feeling off, but there is no known history of diabetes. Mrs. Smith has a past medical history of hypertension and occasional dizziness. Her daughter called 911 when she found her mother confused and unable to answer basic questions.

When EMS arrived, they found Mrs. Smith to be confused, disoriented, and unable to provide a coherent response to basic questions.

Primary Assessment:

- Airway: Patent, no obstruction.

- Breathing: 18 breaths per minute, normal rate and depth.

- Circulation: Pulse 72 bpm, regular. Skin cool, pale, and moist.

- LOC (Level of Consciousness): Confused, disoriented, and unable to recall name or location.

Glucose Level: 45 mg/dL (hypoglycemic).

Secondary Assessment:

- History: Found disoriented by daughter, no recent trauma.

- Physical Exam: No trauma noted. Soft abdomen, no signs of distress.

- Neuro: Confused, pupils equal, round, and reactive. Capillary refill greater than 2 seconds.

Intervention:

- Administered glucose gel (15 grams) while monitoring the patient’s status.

Socratic Questions:

- Why is it important to assess the airway, breathing, and circulation first in any patient, especially one with altered mental status?

- What is the significance of evaluating these life-support functions before addressing the underlying cause of altered mental status?

- What might you suspect is causing Mrs. Smith’s altered level of consciousness based on her clinical presentation?

- What are the possible causes of confusion or disorientation in elderly patients, and how would you prioritize them?

- When you found Mrs. Smith’s blood glucose level to be 45 mg/dL, what immediate actions did you take to manage her condition?

- Why is hypoglycemia a medical emergency, and how does glucose administration help in managing the situation?

- How do you determine the most appropriate treatment for hypoglycemia in a patient who is awake and able to swallow?

- Why would you choose to administer glucose gel in this situation over other possible treatments, such as intravenous glucose?

- What are the key signs that indicate Mrs. Smith is beginning to improve following glucose administration?

- How does improvement in vital signs (e.g., blood glucose level, mental status) influence your ongoing treatment plan?

- What steps should you take during transport to ensure Mrs. Smith remains stable, and how often should you reassess her?

- What specific monitoring is essential during transport for a patient recovering from hypoglycemia?

- What are the important details to include in a handoff report to the receiving healthcare team at the hospital?

- How can you effectively communicate your assessment and interventions to ensure continuity of care and avoid potential errors?

Case Scenario: Full Assessment and Reassessment

Patient Overview:

- Name: Mrs. Martha Smith

- Age: 76 years old

- Chief Complaint: Found disoriented at home by her daughter. Reports minimal food intake today. No known history of diabetes.

- Presenting Signs: Disoriented, confused, unable to provide a coherent response to basic questions.

1. Scene Size-Up:

- Scene Safety: Confirmed the scene is safe, with no apparent hazards.

- MOI (Mechanism of Injury): No trauma or fall noted; likely a medical issue.

- Additional Resources: Called for an ambulance as more advanced care is needed.

2. Primary Assessment:

- Initial Impression: The patient is a 76-year-old woman found confused. The daughter reports that she hasn’t been feeling well and has eaten very little today.

Airway:

- The patient’s airway is open and unobstructed. She is able to talk but exhibits confusion in her speech.

Breathing:

- The patient is breathing at a rate of 18 breaths per minute, with normal depth and effort. No signs of labored breathing or abnormal breath sounds.

Circulation:

- Pulse: 72 beats per minute, regular and strong.

- Skin: Cool, pale, and moist, which can indicate hypoperfusion.

Level of Consciousness (LOC):

- AVPU Scale: Alert but confused. She is unable to recall her name or the current date. When asked about her location, she answers, “I’m not sure.”

- Glucose Check: A glucometer reading of 45 mg/dL confirms hypoglycemia as the cause of altered mental status.

Decision:

- The patient’s blood sugar is dangerously low, and glucose gel (15 grams) is administered. The patient is in a safe position, and swallowing is not compromised.

3. Secondary Assessment:

While waiting for the glucose to take effect, a more detailed secondary assessment is performed.

History:

- SAMPLE History:

- Signs & Symptoms: Confusion, disorientation, cool and pale skin.

- Allergies: None reported.

- Medications: No medications noted, aside from occasional dizziness.

- Past Medical History: Hypertension, dizziness.

- Last Oral Intake: Daughter reports minimal food intake today.

- Events Leading up to Present Illness: Daughter found her confused and called 911.

Physical Exam:

- Head: No visible trauma or injuries.

- Neck: No jugular venous distention or tenderness.

- Chest: Clear to auscultation, no abnormal sounds.

- Abdomen: Soft and nontender.

- Extremities: No obvious deformities or swelling. Capillary refill is greater than 2 seconds, indicating poor perfusion.

- Neuro: Confusion persists, but pupils are equal, round, and reactive to light.

4. Reassessment (5 minutes after glucose gel administration):

The patient is reassessed after 5 minutes.

- Airway: No changes, still clear.

- Breathing: No changes in respiratory rate or effort.

- Circulation: Pulse remains steady at 72 beats per minute. Skin shows a slight improvement in color, less pale than initially.

- LOC: The patient is more aware and begins to recall her name and location but still seems mildly confused.

Vital Signs:

- Pulse: 72 bpm (stable).

- Blood Pressure: 120/78 mmHg (normal).

- Respirations: 18 breaths per minute (unchanged).

- Glucose: 75 mg/dL (still low but improving).

Decision:

- The patient’s condition is improving, but her blood sugar is still below normal. Another dose of glucose gel is administered, and continued monitoring is planned.

5. Reassessment (10 minutes after second glucose gel dose):

The patient is reassessed again.

- Airway: Clear, no distress.

- Breathing: Normal rate and depth.