Chapter 6: Public Health

Suzanne Martens, MD, FACEP, FAEMS, MPH, EMT

Learning Objectives

- Understand the function of Public Health Services

- Understand the support between EMS and Public Health

6.1 Introduction

EMS and Public Health Services share a common mission in protecting and improving the health and safety of individuals and communities. Although the techniques and timelines are often different, there is increasing mutual support and shared end goals. From data sharing and vaccination efforts to emergency preparedness and education, the collaboration between EMS and public health is essential for a healthier, safer society. Together, these systems form a vital partnership that strengthens community resilience.

6.2 What is Public Health?

Public health is defined as the science of protecting the safety and improving the health of communities through education, policy making and research for disease and injury prevention (CDC Foundation).

Modern American public health services started in 1798 with the Marine Hospital Service (MHS), which was created to care for sick and injured seamen. Rules were established for optimal care and treatment, such as:

“Every patient is to be shaved Sunday and Wednesday”

“Every patient is forbidden to spit on the floor”

Successful treatment programs spread outside of the marine hospitals to civilian facilities. One of the first programs recognized was the need to quarantine sick persons to decrease the spread of infectious diseases. The term “quarantine” is a period of 40 days, which was the length of time a ship was held at the dock before allowing potentially contagious persons or cargo to be transferred to land. ** Modern medicine uses more specific methods of isolation and lengths of time depending on the type of infection being contained.

The Marine Hospital Services became the Public Health and Marine Hospital Service, and now the United States Public Health Service (USPHS), established in 1912. An important program created in 1942 was the Malaria Control in War Areas (MCWA), which directly contributed to the establishment of the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), by providing most of the CDC’s original 400 employees.

It is recognized that the U.S. Public Health Service is its own branch of the United States uniformed services alongside the Navy, Army, Coast Guard, Marines, Air Force, Space Force, and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

The goal of public health services is to promote the health and wellbeing of the population at large. This may also be known as health equity. The Public Health Services investigates barriers to health in order to develop support mechanisms. Barriers are often based on socioeconomic status, literacy, race, gender, disabilities, access to care, or safe and stable housing. Public health strives for equity in being able to achieve optimal health and well-being for each person. A strong vision in the Public Health Services is prevention of illness and injury, with forward-looking plans aimed at identified causes. Such examples are wide-ranging, from diabetes to gun violence, tick-borne illnesses to untreated mental health, or tobacco-use cessation to disaster planning and mitigation.

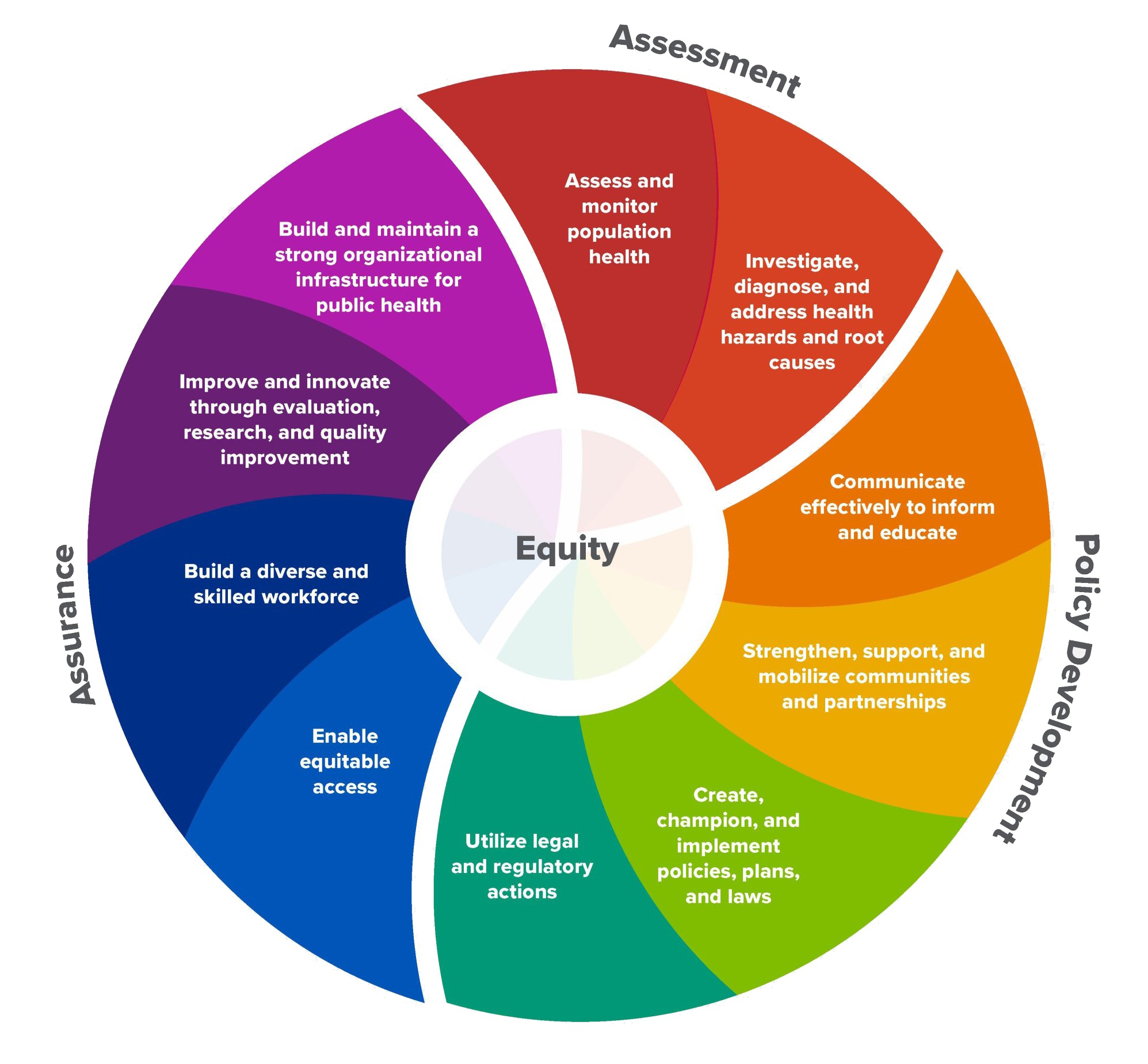

The essential public health services are:

- Assess and monitor population health status, factors that influence health, and community needs and assets.

- Investigate, diagnose, and address health problems and hazards affecting the population.

- Communicate effectively to inform and educate people about health, factors that influence it, and how to improve it.

- Strengthen, support, and mobilize communities and partnerships to improve health.

- Create, champion, and implement policies, plans, and laws that impact health.

- Utilize legal and regulatory actions designed to improve and protect the public’s health.

- Ensure an effective system that enables equitable access to the individual services and care needed to be healthy.

- Build and support a diverse and skilled public health workforce.

- Improve and innovate public health functions through ongoing evaluation, research, and continuous quality improvement.

- Build and maintain a strong organizational infrastructure for public health.

Much of the work involves data collection and discernment of patterns. Best practices are identified with the goal of providing optimal outcomes for all populations. This can require years, if not decades, of effort and development; both in the field and the lab. This is meticulous and detailed work, requiring consistency and attention to detail.

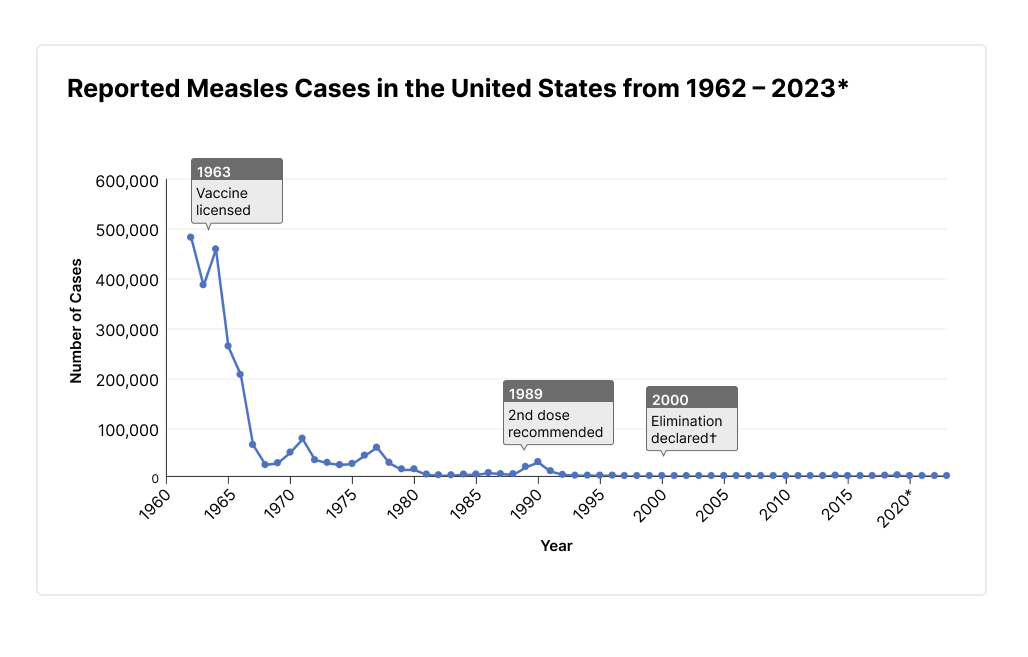

The CDC recognizes the following as the ten greatest public health achievements of the 20th century:

- Control of infectious diseases

- Decline in deaths from heart disease and stroke

- Family planning

- Fluoridation of drinking water

- Healthier mothers and babies

- Immunizations

- Motor vehicle safety

- Safer and healthier foods

- Tobacco as a health hazard

- Workplace safety

*2023 data are preliminary and subject to change. †Elimination is defined as the absence of endemic measles transmission in a region for ≥ 12 months in the presence of a well-performing surveillance system.

Public health successes aimed at improving health equity by focusing on community-wide determinants of health include:

- Laws to protect workers and consumers from companies that treat people unfairly, secure minimum wages and paid leave, and restrict misleading marketing.

- Agreements to secure community-wide broadband access, bringing work, education, and health care opportunities with it.

- Zoning and other policies that protect and promote safe, stable, housing, like proactive rental inspections (to regularly check home safety and fix issues before they become problematic) and inclusionary zoning (to ensure housing options for community members at a range of income levels).

Along with health care support and research responsibilities, the Public Health Services has legal authority to investigate illness or injury cases, with access to protected health information under HIPAA exceptions, and to quarantine, isolate, or detain persons at risk of spreading disease.

Per Title 45 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 164.512 (45 CFR 164.512):

Public Health Activities and Purposes:

- Prevent or control disease or injury

- Conduct surveillance, investigation and intervention

- Notify person exposed to communicable disease or at risk of contracting or spreading CD, if authorized by law to make notification

The Public Health Services have legal authority at all levels, Federal, State, Tribal and Local. It is responsible for both Powers and Duties.

- Powers – Authorize you to act

- Local health officer “may inspect schools and other public buildings. . . to determine. . . sanitary condition.”

- Duties – Require you to act

- Local health officer “shall immediately report to the department” when an outbreak occurs

The Public Health Services is charged with balancing public and personal wellbeing, and is directed to use the least restrictive arrangements to accomplish the goal of public safety. Voluntary cooperation is preferred, but legally enforced restrictions exist. Examples from Wisconsin State Statutes include compelling compliance with:

Seven possible directives:

- Participate in education or counseling

- Participate in treatment for known or suspected condition

- Undergo tests and exams to identify, monitor and evaluate disease

- Notify or appear before local health official to verify status, for testing or for direct observation of treatment

- Stop conduct or employment that is a threat to others

- Reside part-time or full-time in an isolated or segregated setting

- Be placed in an appropriate institutional treatment facility until noninfectious

If isolation or quarantine is ordered:

- May forbid contacts by certain persons

- May use others to guard the quarantine site

- Wis. Stat. 252.06

- May also direct persons who own or supervise property or animals and their environs, which present a threat of transmission of a CD, to abate the threat

- DHS 145.06(6)

A specific subsection pertains to Tuberculosis, where the risk to the public is significant:

- Wis. Stat. 252.07; DHS 145.08 -.12

- Shall at once investigate and make and enforce necessary orders

- May order medical evaluation, directly observed therapy or home isolation if the person does not comply with an order

- May order confinement to a facility

- Different process than for other CDs

- May confine for 72 hours before a hearing

More aggressive and restrictive enforcement will be enacted for high-risk diseases where the contagious person is noncompliant.

- A person is considered to have a known contagious medical condition which poses a threat if:

- The person has been medically diagnosed

and

- Exhibits anyone of the six behaviors listed in DHS 145:

- (1) Has transmitted or (2) likely will transmit

- (3) Refuses or is (4) unable to follow medical regimen

- (5) Misrepresented facts or other (6) willful act that increases the threat of transmission from an epidemiological standpoint

and

- One of the following exists:

- Has been linked epidemiologically to exposure to a known case, or

- Has lab findings indicative of a CD, or

- Exhibits symptoms medically consistent with a CD

The Public Health authority includes emergency powers such as:

- Purchase, store or distribute pharmaceutical agents and medical supplies

- Order compulsory vaccinations

- May designate local health as its agent and grant public health authority powers

- Wis. Stat. 250.041

Additionally, the Public Health Services is charged with environmental health. Under Wisconsin State Statute 254, such duties include:

- Shall report to the department environmental contamination; lead poisoning/exposure

- Shall issue orders to abate lead hazard

- Shall close or restrict access to beaches if human health hazard exists

- Shall enforce state rules to control human disease from animal-borne or vector-borne disease transmission

6.3 Mutual Support Between EMS and Public Health

Public Health gathers data retrospectively but looks for ways to protect the population prospectively, in the future. EMS can contribute to this by providing the most accurate data possible. Completing reports with details such as time of onset, incident location, number of vehicles involved or location of person within the vehicle, and of course signs and symptoms. Note that timely documentation is essential, as there are associated surveillance programs which upload data in real time, such as every 6 hours. This may trigger warnings of developing conditions like a wave of respiratory infections or a shift in overdose exposures.

What is NEMSIS?

The National Emergency Medical Services Information System (NEMSIS) gathers data from EMS reports throughout the United States and territories. This data is compiled, categorized and distributed as reports back to EMS agencies, government, and researchers. The dataset does not contain information that identifies patients, EMS agencies, receiving hospitals, or reporting states.

The 2023 NEMSIS Public-Release Research Dataset includes 54,190,579 EMS activations submitted by 14,369 EMS agencies serving 54 states and territories during the 2023 calendar year.

NEMSIS is a program of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration’s Office of EMS and is hosted at the University of Utah. It is a collaborative system to improve patient care through the standardization, aggregation, and utilization of point of care EMS data at a local, state and national level. Data from NEMSIS is also used to help benchmark performance, determine the effectiveness of clinical interventions, and facilitate cost-benefit analyses.

Public Health can influence EMS practice by sending out notices on emerging trends and diseases. For example, notification of seasonal respiratory diseases such as Influenza or respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) may heighten the awareness of the impact of patients complaining of a cough. Or when multiple students on a college campus are being evaluated for headaches and one was found to have meningitis. Future calls for headaches on campus should include proper personal protective equipment (PPE) to avoid exposure.

The COVID-19 pandemic has provided almost everyone with a glimpse into the operations of the Public Health Services, from the report of the spreading disease even prior to actual identification, to safety recommendations which were further defined and modified, followed by vaccines and antiviral medications, as well as best treatment guidelines. EMS practitioners early in the pandemic essentially lived in PPE while at work. Many chose not to live at home to avoid exposing family members. Standard medical care required modification for safety concerns, such as only administering nebulizer treatments under certain conditions. So many patients were moved to designated isolation wards. Through updates and acquired knowledge, EMS learned which patients were safe to treat at home. This was a fundamental change in patient assessment and treatment goals for EMS.

Another way EMS can integrate, and support Public Health is being available for surge deployments and treatments. COVID provided a backdrop for the need of mass vaccination. EMS practitioners were able to assist with testing and vaccination clinics or even establish their own vaccination clinics within communities.

EMS is unique in our working environment. We go into people’s homes every day. We get to see how they are doing and what the challenges are. EMS provides support and care on a moment’s notice, 24/7/365. When all else fails, people know they can call 911. However, because EMS is focused on each call and each patient, we often do not get a bigger picture; but we can contribute to this with our information and data. By contributing forward, EMS can show the change in illness or injury patterns. More and more metadata programs and systems are uploading and sampling EMS reports for early warnings and trends in infectious disease, overdose waves, injuries from new or changing situations. It is very important that you document your incidents, assessments, vital signs, and care provided very specifically, so this may be used to note these changes sooner rather than later.

EMS Metadata Dashboards

Visit the following websites to view visual demonstrations of how EMS data can be used:

California Emergency Medical Services Authority

National Integrated Heat Health Information System – EMS HeatTracker Tool

911 Records with influenza-like-illness EMS Provider Impressions – ESO

Expert Opinion

An excerpt from HealthcareITNews:

At HIMSS24, Erica Matti, senior analyst at the University of Michigan’s Center for Health and Research Transformation, and Joshua Legler, an EMS data consultant for the National Emergency Medical Services Information System’s Technical Assistance Center, emphasized the experience of these healthcare clinicians and their vital need for healthcare data exchange in the field.

“Accurate data is really important for them to be able to accurately present information about your condition to the rest of your healthcare team and treat you in the field,” said Matti, as she described the value that more widely used EMS data could also bring to healthcare delivery.

In addition to real-time information, that data can offer visibility into patients’ social determinants of health that is often richer than yes/no patient responses to SDOH questionnaires, she said.

NEMSIS data standards and protocols are used across the country by EMS record systems that undergo compliance testing.

Legler said about 30 software vendors exchange data with each other and to state databases, and ultimately, to a national EMS database that amasses approximately 50 million EMS encounter records per year.

“So, [it’s] a great ecosystem within EMS,” he said. “What we need to do is look at how EMS interrelates with the rest of healthcare.”

Matti described how EMS data can be eye-opening for SDOH measures in her experience as a public health nurse and in her work with the Michigan Health Information Network Shared Services.

“Often, EMS clinicians are the first point of contact for people with emerging healthcare needs,” she said, noting that community paramedics serve patients who primarily access the healthcare system through nontraditional pathways.

When they encounter the patient where they are, EMS clinicians have a front-row seat to that patient’s circumstances and can assess their SDOH determinants.

For example, a patient may answer yes when asked if “they have housing” when seeking care at a brick-and-mortar location, but when a paramedic arrives at their location when called, “they can tell right away this person is couch surfing,” said Matti.

“Maybe they see the same patient three or four times this month, and every time it’s in a new location,” she continued. “Or maybe the home they’re staying in has absolutely no water. Well, that’s not really housing, is it?”

6.4 Community EMS

EMS is able to participate in Community EMS for ongoing and long-term care. This is a newer section in EMS and has many versions. In some areas this is called Mobile Integrated Health (MIH). The challenge for Community EMS is that every community has different needs. Identifying and providing these are challenging. The most common question is: Why do we need Community EMS when we already have home health care or visiting nurses? The advantage in EMS is that we already work in the homes of our citizens, and we are used to being available on a moment’s notice. Being recognized as a complimentary support section in healthcare is a positive progression for EMS.

Community EMS is more in alignment with Public Health in that it is more proactive, rather than traditional EMS being mostly reactive. Some examples of community programs are hospital discharge safety checks, short-term medication administration, county-wide pediatric asthma home assessments, OB checks, wound care checks, and congestive heart failure maintenance programs. The seemingly counterintuitive goal for an EMS practitioner is to keep the patient out of an ambulance or an emergency department, by treating them at home. Establishing this type of program requires community and primary care input, support, and teamwork. It is not a simple task.

Newer programs in support of community mental health are growing. It has been recognized that often an EMS practitioner along with a mental health provider or social worker is more appropriate in crisis situations than law enforcement. This is a unique situation in which extended time spent on scene is a benefit, which is not the typical EMS circumstance. Spending time, providing supportive care, arranging forward interventions, and not forcing transport to the emergency department are key elements of behavioral health crisis interventions.

North Carolina Task Force for Racial Equity in Criminal Justice

Communities have begun changing how they respond to non-violent 911 calls related to behavioral health crises or social issues like homelessness. These Alternative Emergency Responses (AER) may include co-responders, where a law enforcement officer is paired with a behavioral health professional, or non-law enforcement responders who are behavioral health specialists.

Leaders often point to three particular alternative response models: Co-Responder teams; STAR (Support Team Assisted Response); and (Crisis Assistance Helping Out in The Streets). The essential component of each model is the utilization of specialized clinicians (social worker/mental health clinician) in partnership with law enforcement or EMS. CAHOOTS (Crisis Assistance Helping Out in The Streets). The essential component of each model is the utilization of specialized clinicians (social worker/mental health clinician) in partnership with law enforcement or EMS.

A Co-Responder model dispatches either a social worker or mental health clinician along with law enforcement on crisis calls. In both the CAHOOTS and STAR model, a crisis worker or mental health clinician is paired with a paramedic to respond to calls related to non-violent and non-criminal emergencies such as drug overdoses, suicidal individuals, intoxication, indecent exposure, trespass/unwanted person, and syringe disposal.

6.5 EMS Agenda 2050

To illustrate the alignment of EMS with Public Health goals, some of the vision statements from the EMS Agenda 2050 are pertinent.

-

INHERENTLY SAFE AND EFFECTIVE

- The entire EMS system, from how care is accessed to how it is delivered, is designed to be inherently safe and to minimize exposure of people to injury, infections, illness or stress. Decisions are made with the safety of patients, bystanders, the public and practitioners as a priority, from how people are moved to hygiene practices in the field and in the ambulance. Clinical care, operations and other aspects of the system are based on the best evidence in order to deliver the most effective service, with a focus on outcomes determined not only by the EMS service but by the entire community and the individuals receiving care.

-

INTEGRATED & SEAMLESS

- Healthcare systems, including EMS, are fully integrated with each other and with the communities in which they operate. Additionally, local EMS services collaborate frequently with their community partners, including public safety agencies, public health, social services and public works. Communication and coordination between different parts of the care continuum are seamless, leaving people with a feeling that one system, comprising many integrated parts, is caring for them and their families.

-

SOCIALLY EQUITABLE

- In a socially equitable system, access to care, quality of care and outcomes are not determined by age, socioeconomic status, gender, ethnicity, geography or other social determinants. In every community in the nation, EMS systems provide any resident or visitor the best possible care and services, in order to maintain the health of individuals and populations. Caregivers feel confident and prepared when caring for children, people who speak different languages, persons with disabilities or other populations that they may not interact with frequently.

6.6 Summary

Emergency Medical Services and the Public Health Services are mutually supportive. EMS works to identify and care for people in crisis and is often on the leading edge of a surge in illness or injuries. With its overall view, Public Health is better equipped to recognize these changes, gather data from multiple sources, and provide guidance. Public Health also supports EMS with safety, health, and mental health best practices as part of its overall goal to achieve health equity and disease prevention in the population.

6.7 Glossary of Terms

Community: is a group of people who have common characteristics; communities can be defined by location, race, ethnicity, age, occupation, interest in particular problems or outcomes, or other similar common bonds. Ideally, there would be available assets and resources, as well as collective discussion, decision-making and action. (Turnock, BJ. Public Health: What It Is and How It Works. Jones and Bartlett, 2009)

Contagious (or communicable) diseases: are capable of spreading from one person to another. All contagious diseases are infectious; but not all infectious diseases are contagious.

Epidemic: occurrence in a community or region of cases of an illness, specific health-related behavior, or other health-related event clearly in excess of normal expectancy. Both terms are used interchangeably; however, epidemic usually refers to a larger geographic distribution of illness or health-related events.

Equity: is defined as a fair and just opportunity for all to achieve good health and well-being. This requires removing obstacles to health such as poverty and discrimination and their consequences, including powerlessness and lack of access to good jobs with fair pay, quality education and housing, safe environments, and healthcare. It also requires attention to health inequities, which are differences in population health status and mortality rates that are systemic, patterned, unjust, and actionable, as opposed to random or caused by those who become ill.

Health: is a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity. The bibliographic citation for this definition is: Preamble to the Constitution of WHO as adopted by the International Health Conference, New York, 19 June – 22 July 1946; signed on 22 July 1946 by the representatives of 61 States (Official Records of WHO, no. 2, p. 100) and entered into force on 7 April 1948. The definition has not been amended since 1948.

Healthcare sector: is defined as entities that provide clinical services, mental health services, oral health services, provide or pay for services for individuals, or facilitate the provision of services to individuals. Entities in this sector may include hospitals, health systems, health plans, health centers, behavioral health providers, oral health providers, etc.

Infectious diseases: are illnesses caused by germs (such as bacteria, viruses, and fungi) that enter the body, multiply, and can cause an infection. Some infectious diseases are contagious (or communicable), meaning they are capable of spreading from one person to another.

Intervention: action or ministration that produces an effect or is intended to alter the course of a pathologic process.

Isolation: separates sick people with a contagious disease from people who are not sick.

Law(s): refer to the aggregate of statutes, ordinances, regulations, rules, judicial decisions, and accepted legal principles that the courts of a particular jurisdiction apply in deciding controversies brought before them. The law consists of all legal rights, duties, and obligations that can be enforced by the government (or one of its agencies) and the means and procedures for enforcing them. (Garner, B.A. editor. Black’s Law Dictionary. 8th ed. West Group; 2004)

Pandemic: denoting a disease affecting or attacking the population of an extensive region, country, or continent.

Population health: is the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group. The field of population health includes health outcomes, patterns of health determinants, and policies and interventions that link these two. Population health approaches are community or policy non-clinical approaches that aim to improve health and wellbeing of a group of individuals. This differs from population health management which refers to improving clinical health outcomes of individuals through improved care coordination and patient engagement supported by appropriate financial and care models. (Adapted from Kindig and Stoddart)

Prevention: action so as to avoid, forestall, or circumvent a happening, conclusion, or phenomenon (e.g., disease).

Public health: is defined as the science of protecting the safety and improving the health of communities through education, policymaking, and research for disease and injury prevention. (CDC Foundation)

Quarantine: separates and restricts the movement of people who were exposed to a contagious disease to see if they become sick. These people may have been exposed to a disease and do not know it, or they may have the disease but do not show symptoms.

Research: is a systematic investigation, including research development, testing, and evaluation, designed to develop or contribute to generalized knowledge. (United States Department of Health and Human Services. Healthy People 2020. Washington, DC)

Community-based Participatory Research (CBPR): is a collaborative approach to research that equitably involves all partners in the research process and recognizes the unique strengths that each brings. CBPR begins with a research topic of importance to the community, has the aim of combining knowledge with action and achieving social change to improve health outcomes and eliminate health disparities. (W. K. Kellogg Foundation, Community Health Scholars Program, 2001 quotes from Minkler M, and Wallerstein N, editors. Community-Based Participatory Research for Health. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass Inc.; 2003)

References:

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (n.d.). Public health key terms [PDF]. https://www.cdc.gov/training-publichealth101/media/pdfs/public-health-key-terms.pdf

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2021). The roots of public health and CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/museum/online/story-of-cdc/roots/index.html#:~:text=The%20nation%27s%20first%20public%20health,personnel%20who%20provided%20medical%20care

Digital Communications Division. (2022). What is the difference between isolation and quarantine? HHS.gov. https://www.hhs.gov/answers/public-health-and-safety/what-is-the-difference-between-isolation-and-quarantine/index.html

EMS Agenda 2025. (2021). The different types of EMS services. https://emsagenda2050.org/the-different-types-of-ems-services/

Fox, A. (2024). Tapping into the trove of standardized EMS data. Healthcare IT News. https://www.healthcareitnews.com/news/tapping-trove-standardized-ems-data

Indiana University. (n.d.). Communicable diseases: Infectious diseases. Protect IU. https://protect.iu.edu/environmental-health/public-environment/communicable-diseases/index.html

Malofsky, S. (n.d.). Public health law [PowerPoint Slides]. Office of Legal Counsel/Department of Health Services. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/lh-depts/orientation/phlaw.pdf

NEMSIS. (n.d.). What is NEMSIS? https://nemsis.org/what-is-nemsis/

North Carolina Task Force for Racial Equity in Criminal Justice. (2023). Re-imagining 9-1-1: The case for alternative emergency response [PDF]. https://ncdoj.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/TREC_Reimagining-911_InfoSheet.pdf

Public Health Accreditation Board. (2020). The 10 essential public health services [PDF]. https://phaboard.org/wp-content/uploads/EPHS-English.pdf

Public Health Authority: FAQs. (n.d.). Act for public health. https://actforpublichealth.org/public-health-authority/

Publichealthcareeredu.org. (2021). What is public health? https://www.publichealthcareeredu.org/what-is-public-health/

Wisconsin Department of Health Services. (2025). Community EMS forum. https://www.dhs.wisconsin.gov/ems/community-ems.htm

Images:

Figure 6.1: ”United_States_Public_Health_Service_%28seal%29” by user:Militaryace is in the Public Domain.

Figure 6.2: ”10essentialpublichealthservices” by Public Health National Center for Innovations is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.cdc.gov/public-health-gateway/php/about/index.html

Figure 6.3: “Static map” by US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://www.cdc.gov/measles/data-research/.

Figure 6.4: “Map.jpg” by unknown author for CDC is in the Public Domain. Access for free at https://web.archive.org/web/20241125065154/https://blogs.cdc.gov/publichealthmatters/2022/05/ems-week/