Chapter 9: Speech Preparation

9.0 Introduction

Learning Objectives:

- Identify the elements of effective oral presentations

- Analyze possible causes of communication apprehension

- Plan a presentation for a specific audience, purpose, and situation

- Develop an effective organizational pattern

- Incorporate sufficient supporting material and research

- Use an extemporaneous delivery style

- Apply effective nonverbal communication to engage the audience

- Use effective and appropriate language

Oral presentations are a cornerstone of effective communication, whether in academic, professional, or personal settings. A well-delivered presentation can inform or persuade audiences, while a poorly executed one can lead to confusion and disengagement. This chapter explores the key elements of effective oral presentations, from planning and organization to delivery and engagement. By the end of this chapter, you’ll have the tools to deliver compelling presentations that captivate your audience and achieve your goals.

A Short Story: The Power of Preparation

Argentino, an architect, was tasked with presenting his firm’s innovative sustainable building design to the city’s skeptical planning committee. Despite his deep expertise in sustainable architecture, he felt nervous about securing approval for such a forward-thinking project. To prepare, he meticulously researched the committee members’ priorities and past concerns, organized his complex technical data into clear, digestible sections, and crafted compelling visual aids, including dynamic 3D models. He practiced his presentation countless times, refining his explanations of the design’s environmental benefits and anticipating tough questions about budget implications and long-term viability.

On the day of the presentation, Argentino’s thorough preparation shone through. He confidently articulated his vision, using his visuals and precise language to convey the design’s elegance and efficiency. He maintained strong eye contact, addressing committee members’ concerns directly and thoughtfully. His presentation was a resounding success, earning enthusiastic praise from the committee and securing crucial approval for the groundbreaking project.

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ A person is presenting to a group with images of building design showing on a screen behind them](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/74/2025/04/aitubo-4-1.jpg)

This story highlights the importance of preparation and effective delivery in oral presentations. In this chapter, we’ll explore how to plan, organize, and deliver presentations that leave a lasting impact.

9.1 Identify Elements for Effective Oral Presentations

Crafting a compelling oral presentation is a multifaceted process that requires attention to several interrelated elements (Zarefsky & Engels, 2021). At the heart of any effective presentation lies a clear purpose, which ensures that every part of the message contributes to a specific goal. That purpose must be tailored to the intended audience by taking into account their needs, interests, and expectations. To deliver the message successfully, the presentation must follow a logical structure that organizes ideas into a coherent flow, guiding the audience smoothly from beginning to end (Hillmer, 2022). Engaging content, such as relevant stories, illustrative examples, and vivid visuals, is essential for capturing attention and making the presentation memorable. Equally important is delivery: confident use of both verbal and nonverbal communication builds credibility and strengthens the connection with listeners (Broeckelman-Post et al., 2020; Khoirunisa & Pratama, 2024). Supporting materials, including research findings, statistics, and expert opinions, reinforce arguments and enhance persuasiveness by grounding the message in evidence (Munz et al., 2024). Mastering these elements provides both the vocabulary to analyze presentations and the methodology to improve them.

Key Elements for Effective Presentations

Oral presentations are generally evaluated on two primary dimensions: content and delivery. Both are essential, as strong content loses impact without effective delivery, while confident delivery cannot compensate for weak or poorly structured content. When preparing a speech, careful attention to both dimensions will help ensure that the message is impactful, credible, and well-received.

Content Elements

The content of an effective presentation is carefully planned, precise, and supported with credible evidence. A clear and specific purpose serves as the compass for the entire presentation, ensuring that every part of the speech – whether to inform, persuade, or entertain – contributes to the central goal. For example, if the purpose is to persuade colleagues to adopt new project management software, the presentation must provide research, data, and examples to support that position.

Understanding the audience is central to content design. Analyzing the audience allows the speaker to adapt language, examples, and complexity to their level of knowledge, interests, and possible biases. For a group of experts, technical detail and specialized terminology may be appropriate, while for a general audience, simpler explanations and relatable examples will ensure accessibility.

A clear organizational structure further strengthens the content. Every effective presentation includes three essential parts: an introduction, a body, and a conclusion. The introduction should capture attention, establish credibility, state the specific purpose, and preview the main points. The body should develop the argument through distinct, well-defined points supported by sub-points and evidence. The conclusion should summarize the message, reinforce the thesis, and leave the audience with a memorable closing thought. When content is tightly aligned with purpose, structured logically, and supported by credible material such as anecdotes, statistics, and expert testimony, the result is a message that is both coherent and persuasive.

Presentation Elements

In addition to strong content, the effectiveness of a presentation depends heavily on how it is delivered. Voice is one of the most powerful tools available to a speaker. Presentation elements such as volume, pitch, tempo, and pauses shape how a message is received, while careful articulation and the avoidance of filler words enhance professionalism and clarity.

Nonverbal communication is equally important. Eye contact, gestures, posture, and facial expressions all convey meaning, reinforcing the verbal message and helping to build rapport with the audience. Confident and appropriate nonverbal cues signal credibility and enthusiasm.

The method of delivery also plays a role in presentation success. Whether the speech is delivered impromptu, from memory, from a manuscript, or in an extemporaneous style, the choice affects both naturalness and flexibility. Extemporaneous delivery, in particular, allows for a conversational tone while ensuring that the key points are covered.

The use of presentation aids can enhance understanding when they are clear, relevant, and purposeful. Visual aids such as slides, charts, or props, and audio aids when appropriate, should support the spoken message by illustrating complex ideas or reinforcing important information, rather than distracting from it.

Finally, time management is an often-overlooked but critical element. Staying within the allotted time demonstrates respect for the audience and ensures that the presentation remains focused. Practicing with timing in mind allows the speaker to refine the flow, prioritize main ideas, and, if desired, leave space for questions or discussion.

Bringing Content and Presentation Together

An effective presentation results from the integration of strong content with confident and purposeful delivery. When both are carefully considered and balanced, the message becomes clearer, more engaging, and more persuasive. By paying attention to these key elements and adapting them to the audience and situation, speakers can enhance their ability to communicate ideas effectively in any context.

9.2 Analyze Possible Causes of Communication Apprehension

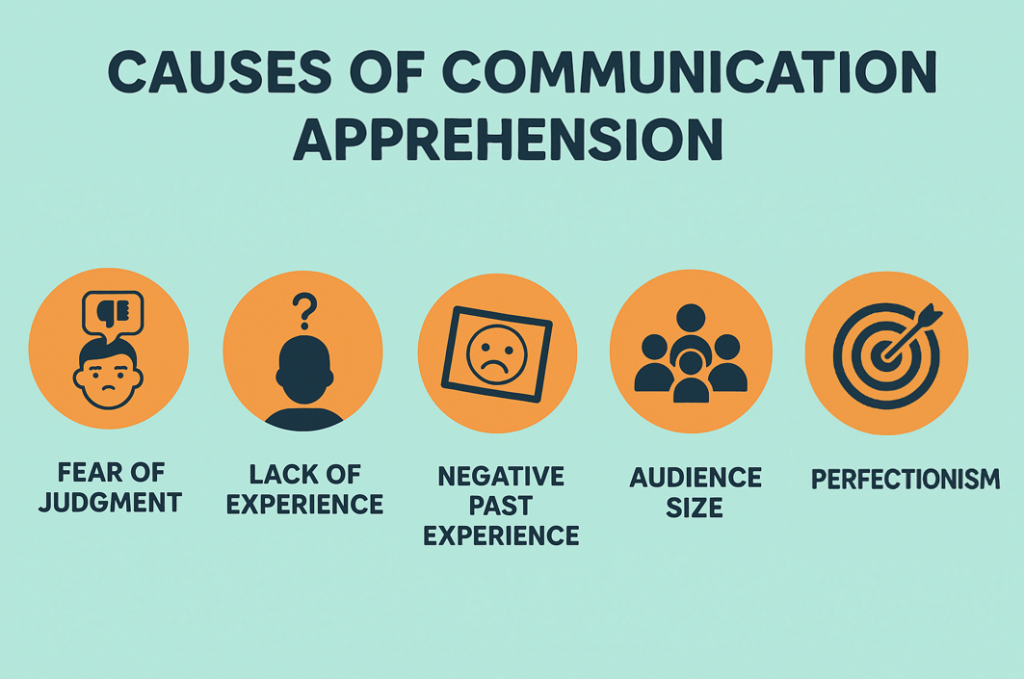

Communication apprehension, often referred to as public speaking anxiety, is a widespread challenge that can hinder even the most capable individuals (McCroskey, 1977; McCroskey, 1984; Beatty et al., 1998; Grieve et al., 2021). This anxiety stems from a variety of sources, including the fear of judgement, lack of experience, pressure of perfectionism, negative past experiences, and audience size (Raja, 2017). However, these apprehensions are not insurmountable (Thompson, 2024). By employing effective strategies (Brandrick et al., 2021) – such as consistent practice, detailed visualization, calming deep breathing techniques, a focused approach that centers on the message, and the gradual buildup of experience by starting small – individuals can manage and overcome their anxiety, transforming potential fear into confident and impactful presentations.

Causes of Communication Apprehension

Fear of Judgment

This is perhaps the most pervasive form of communication apprehension. It stems from the fear of placing oneself in a position where others will evaluate one’s thoughts, ideas, and persona. It’s not just fear of outright criticism, but also fear of subtle disapproval, perceived incompetence, or appearing foolish. This fear can be amplified by a perceived power dynamic between the speaker and the audience (e.g., presenting to superiors, experts, or authority figures). The anxiety can lead to self-consciousness, causing speakers to focus excessively on their perceived flaws rather than their message.

A prime example is when a student who is giving a presentation to a class of peers and is worried that they will be judged or laughed at if they make a mistake. As a result, this fear can manifest as physical symptoms (e.g., trembling, sweating, racing heart) and cognitive distortions (e.g., catastrophizing, negative self-talk). This is a common concern regarding speech requirements in college.

Lack of Experience

Just as with any skill, proficiency in public speaking develops with practice. Individuals with limited experience may feel unprepared, uncertain about their abilities, and overwhelmed by the perceived complexity of the task. This anxiety is often tied to a lack of familiarity with the structure, format, and etiquette of presentations. A lack of preparation, uncertainty about how to handle unexpected situations, or unexpected questions from the audience can exacerbate the feeling of being unprepared. Thus, the more a student prepares and practices for the speech, the confidence grows.

A common example is when a professional who is giving their first presentation at a large conference feels nervous about speaking in front of so many people. This can display itself as increased thoughts of imposter syndrome, inability to focus on content rather than performance, and amplify communication apprehension. This can lead to procrastination, avoidance of speaking opportunities, and a self-fulfilling prophecy of poor performance.

Perfectionism

While striving for excellence is admirable, a focus on perfection can create undue pressure and anxiety. The fear of making even a minor mistake can become debilitating. Perfectionists often set unrealistic standards for themselves, leading to self-criticism and a sense of inadequacy. The fear of imperfection can lead to excessive rehearsal, obsessive speech editing, and a rigid delivery style that lacks spontaneity.

For example, a person giving a presentation in front of their boss might be so focused on impressing them that they become obsessed with perfection. This can result in burnout, reduced enjoyment of speaking opportunities, and a heightened sense of anxiety.

Negative Past Experiences

Previous embarrassing or traumatic speaking experiences can create lasting anxiety and a fear of recurrence. Even seemingly minor incidents, such as stuttering, forgetting lines, or receiving negative feedback, can create a negative association with public speaking. These experiences can lead to learned helplessness, where individuals believe they are incapable of improving their speaking skills.

For instance, a person who, as a child, was laughed at during a school presentation may carry with them a lower level of confidence. This can increase over time based on the number of negative judgments that a person receives. This can lead to avoidance of speaking opportunities, a negative self-image as a speaker, and a cycle of anxiety.

Audience Size

The number of people in an audience can significantly impact a speaker’s anxiety level. In a large audience, audience members may feel anonymous and not pay attention. A speaker may find it harder to connect with individual audience members, and they may have a more intense feeling of being judged. The perceived pressure to perform well increases with audience size, as the potential for judgment is multiplied. The physical environment of a large venue, such as a large stage or auditorium, can also contribute to anxiety.

An example is a best man giving a toast at a wedding who could be uncomfortable with the number of guests at the reception. This can lead to increased physiological symptoms, such as rapid heartbeat and shallow breathing, as well as cognitive distortions, such as feeling overwhelmed or intimidated.

Overcoming Communication Apprehension

Rehearsal is the cornerstone of effective public speaking. Familiarity with the material and the flow of the presentation reduce uncertainty and builds confidence. A few strategies are to conduct multiple rehearsals, vary your practice, focus on fluency, practice with notes, and practice with vocal variety. In conducting multiple rehearsals, refrain from running through the presentation just once. Practice multiple times, ideally in conditions similar to the actual presentation (e.g., standing, using visual aids, timing yourself). It is important to vary your practice, where you practice in front of a mirror, record yourself, or present to a trusted friend or family member for feedback. It is helpful to focus on fluency, where you practice transitions between points to ensure a smooth and natural flow. If you plan to use notes, it is vital to practice with them so you are not reading them verbatim. Practicing your vocal variety can help you change your vocal tone, pitch, and volume to keep the audience engaged.

Visualization is another technique to help prepare. Mental rehearsal can supplement physical practice. By visualizing a successful presentation, you can prime your mind for positive outcomes. Imagine every aspect of the presentation, from entering the room to delivering the final remarks. It is helpful to visualize yourself speaking confidently, engaging the audience, and receiving positive feedback. Visualize yourself handling potential challenges, such as unexpected questions or technical difficulties, with poise and confidence. In your visualization, picture the audience, hear your own voice, and feel the sense of accomplishment.

Deep-breathing practices also can help public speaking. Physiological symptoms of anxiety, such as rapid heartbeat and shallow breathing, can exacerbate communication apprehension. Deep-breathing techniques can calm the nervous system and promote relaxation. Using diaphragmatic breathing, where you practice deep, slow breaths from the diaphragm, allowing your abdomen to expand and contract. You can use 4–7–8 breathing, and this is when you inhale for 4 seconds, hold for 7 seconds, and exhale for 8 seconds. This technique can slow down your heart rate and promote relaxation. Practice deep breathing before your presentation and during pauses to maintain composure. Combine deep breathing with other relaxation techniques, such as progressive muscle relaxation or mindfulness meditation.

It is essential to stay focused on your message of the speech. Shifting your focus from your own anxiety to the value you’re providing to the audience can reduce self-consciousness and increase confidence. Remember that your presentation is about serving your audience’s needs and interests. Focus on the key takeaways and benefits that your audience will gain from your presentation. Let your passion for the topic shine through, as genuine enthusiasm can be contagious. Use inclusive language like “us” and “we” instead of “you” and “me,” and engage with your audience to create a connection. If you truly believe that the information you’re providing is valuable, it will be easier to focus on that, instead of your own anxiety.

It is natural to try to accomplish everything for public speaking, but it is important to start small: give yourself small tasks to avoid overwhelming the process. Gradually increasing the size and complexity of speaking opportunities can help build confidence and reduce anxiety. Begin by presenting to small, supportive audiences, such as friends, family, or colleagues. Seek out opportunities to speak in low-pressure situations, such as team meetings or small group discussions. Consider joining a public-speaking group, such as Toastmasters, to receive constructive feedback and practice in a supportive environment. Increase the size and formality of your speaking engagements as your confidence grows. Acknowledge and celebrate your progress, no matter how small, to reinforce positive behaviors.

Real-World Application

9.3 Plan the Presentation for a Specific Audience, Purpose, and Situation

Effective oral presentations are not created in a vacuum; they are carefully crafted to resonate with a particular audience, fulfill a specific purpose, and adapt to a given situation (Seiler et al., 2021). This requires a strategic planning process that begins with clearly defining your purpose and establishing the desired outcome of your presentation (Scott et al., 2024). Next, a thorough analysis of your audience is crucial, allowing you to tailor your content and delivery to their unique needs and interests. It’s equally important to adapt to the situation, considering factors such as time constraints, venue, and available resources (Cingi, 2023). To ensure a clear and lasting impact, you must develop key messages, identifying the core takeaways you want your audience to remember. Finally, selecting appropriate supporting materials, such as examples, data, and visuals, strengthens your message and enhances its credibility (Lucas & Stob, 2020). By thoughtfully addressing each of these planning strategies, you can create a presentation that is not only informative and engaging, but also precisely tailored to achieve its intended goal.

Steps for Planning a Presentation

Define Your Purpose

Establishing a clear purpose is the first and most crucial step in planning a presentation. It acts as a guiding principle, shaping your content, structure, and delivery. The types of purpose include:

- Inform: To educate, explain, or provide information to your audience. Examples include training sessions, instructional presentations, and research reports.

- Persuade: To influence your audience’s beliefs, attitudes, or actions. Examples include sales pitches, advocacy presentations, and proposals.

- Entertain: To engage and amuse your audience. Examples include toasts, after-dinner speeches, and roasts.

As you are considering what type of presentation you are going to give, go beyond general categories. Come up with specific and attainable objectives. The specific purpose statement in a speech is a concise, single infinitive phrase that clearly states what the speaker hopes to achieve with their audience by the end of the presentation. It combines the general purpose (to inform, persuade, or entertain) with the specific topic and desired outcome: for example, to persuade my audience to adopt a plant-based diet for its environmental and health benefits. Ensure that every element of your presentation directly supports your defined purpose. Eliminate any content that is irrelevant or distracting.

Analyze Your Audience

Understanding your audience is essential for tailoring your presentation to their specific needs and interests. The demographics of your audience help consider factors such as age, gender, education level, cultural background, and professional experience. Assess the knowledge level of your audience’s existing knowledge of the topic to determine the appropriate level of detail and complexity. Identify what your audience cares about and what they want to gain from your presentation. Be mindful of cultural differences and adapt your language and delivery accordingly. Be aware of any potential biases or preconceived notions that your audience may hold. Be prepared to adapt your presentation based on audience feedback during the presentation. Use surveys, questionnaires, and informal conversations to gather information about your audience if possible.

Adapt to the Situation

The context in which you deliver your presentation can significantly impact its effectiveness. The potential types of contexts are time constraints, venue, technical resources, and environmental factors. It is vital to adhere to the allotted time and prioritize key messages. This is where practicing comes in handy to help ensure time efficiency. The venue plays an important role in a speech, so consider the size, layout, and acoustics of the venue. Similarly, ensure that you have access to and are proficient in using any necessary technology, such as projectors, microphones, and presentation software. Plan ahead by looking at any potential distractions or interruptions, such as lighting, noise, or temperature.

Develop Key Messages

Identifying the main points you want your audience to remember ensures that your presentation has a clear and lasting impact. To achieve this, you need to craft key messages that are not only easy to understand but also memorable. This means using concise, straightforward language and avoiding jargon that could confuse your audience. You should organize these messages in a logical sequence that guides your audience through a clear narrative, reinforcing your overall purpose.

Throughout your presentation, you must reinforce your key messages to make them stick. The most effective way to do this is by strategically using citations, examples, stories, and visuals. Citations from credible sources provide authority and credibility to your claims. Examples and anecdotes make abstract concepts relatable and emotionally resonant. Visuals like charts, graphs, and images can reinforce a point by engaging your audience through a different channel, helping them to remember the information long after your talk is over. To avoid overwhelming your audience, limit yourself to a few key messages, and be sure to summarize them at the end of your presentation to drive home your main points.

Choose Supporting Materials

Once you have your key messages, you must choose appropriate supporting materials to provide evidence, credibility, and clarity. The most effective supporting materials fall into four key categories:

- Examples and Anecdotes: These are concrete examples and relatable stories that illustrate your points. They give your audience something tangible to connect with and help make your message more personal and memorable.

- Data and Statistics: Credible data and statistics provide objective proof for your claims. They add weight and authority to your message, but remember to always verbally cite your sources to maintain credibility and transparency.

- Audio/Visual Aids: Tools like charts, graphs, images, and short videos are invaluable for strengthening both understanding and engagement. They should simplify complex information and add a visual dimension to your words, but always ensure they are relevant, easy to understand, and not distracting.

- Expert Opinions: Orally citing experts in your field adds a layer of credibility and authority to your message, showing your audience that your ideas are supported by respected voices.

When choosing any supporting material, it is helpful to consider its relevance to your message and audience. Regardless of the material, always ensure you provide proper citations to maintain credibility, and that any audio/visual aids are appropriate and easy to understand.

Develop an Organized Structure

A well-organized structure of your presentation provides a logical framework, making it easier for your audience to follow and understand your message. The common structure is introduction, body, and conclusion, which follow a classic structure to provide a clear beginning, middle, and end.

Develop the Introduction

The introduction is your audience’s first impression, serving several critical purposes: to capture attention, establish your credibility, state your purpose, and preview your main points. It should be concise yet compelling, drawing your audience in and preparing them for your message.

Attention-Getter

It is common practice to start with an attention-getter, where you start with something that immediately hooks your audience. This could be a compelling story, a surprising statistic, a rhetorical question, a relevant quotation, or even a brief, engaging activity. An example is, “Imagine waking up one morning to find your entire digital life – photos, documents, bank accounts – completely inaccessible. This nightmare scenario is becoming an increasingly common reality for individuals and businesses alike.”

Relevance to Audience

It is vital to emphasize the importance of your speech and clearly explain why your topic matters to the audience. Connect your message to their interests, needs, or existing knowledge. An example is, “Understanding basic cybersecurity practices isn’t just for IT professionals; it’s essential for anyone who uses a smartphone, computer, or the internet, because these devices directly impact your personal security and financial well-being.”

Establish Credibility

As a public speaker, you want to establish your credibility early on by briefly explaining why you are qualified to speak on your topic. A strong credibility statement isn’t about boasting; it’s about building a foundation of trust with your audience. You can achieve this by highlighting your relevant experience, such as years of professional practice or successful projects. You might also mention specific research you have conducted or your deep personal passion for the subject. By concisely communicating your background and connection to the topic, you show your audience that you are an authority worth listening to, which makes them more receptive to your message from the very beginning.

Thesis Statement

A thesis statement is when you present the central idea or argument of your entire presentation in one clear, concise sentence. This is your core message. For example, “By the end of this presentation, you will be equipped with practical strategies to protect yourself from the most common causes of sleep deprivation.”

Preview Main Points

Briefly outline the key areas you will cover in the body of your presentation. This acts as a roadmap, helping your audience follow your logical structure. For example, “Today, we’ll discuss the critical role of physical exercise to prepare the body for sleep, eliminating screen time before going to sleep, and the importance of having a nightly routine.”

Develop the Body

The body of your presentation is where you develop your main points, provide detailed information, and present the evidence that supports your thesis. This is typically the longest part of your presentation and should be carefully structured.

Main Points

Organize your overall message into three distinct, well-defined main points. Each main point should directly support your thesis. An example is, “Developing a consistent sleep schedule significantly improves overall health. Creating an optimal sleep environment further enhances sleep quality. Monitoring your sleep will provide you an approach to adapt your sleep plans to feel better upon waking.”

Sub-Points

Under each main point, include relevant sub-points that elaborate, explain, or clarify the main idea. For example, “To develop a consistent sleep schedule, one should set a regular bedtime and wake-up time, even on weekends. Additionally, avoiding daytime naps, especially long ones, can help regulate your sleep cycle.”

Supporting Material

For every sub-point, provide strong supporting material to make your message credible and engaging. This can include examples, anecdotes, statistics, research findings, expert testimony, visuals, or demonstrations. Ensure your support is diverse, credible, and directly relevant.

An example is of research findings as supporting material is, “A study published in the journal Sleep Health, which found that individuals who maintained a consistent sleep schedule reported higher levels of energy and improved mood compared to those with irregular sleep patterns. Furthermore, research from the National Sleep Foundation indicates that even short naps can disrupt nighttime sleep if taken too close to bedtime.”

Use Transitions for Cohesion

Using clear transitions is essential for a smooth and effective presentation. Think of transitions as bridges that smoothly move your audience from one main point to the next, helping them follow your logical flow without getting lost. A good transition lets your audience know where you’ve been and where you’re going. For example, a phrase like, “Now that we’ve explored the importance of a consistent sleep schedule, let’s turn our attention to how creating an optimal sleep environment can further enhance your rest,” effectively links two separate ideas and guides the audience forward. This is even more important in a public speech than in a conversation because your audience cannot interact to ask for clarification.

To create this seamless flow, speakers use signposting, which involves using clear signals like “First,” “Second,” or “Finally.” These simple verbal cues help organize your thoughts and provide a clear roadmap for your audience. Together, transitions and signposting ensure your presentation has a cohesive logical flow, preventing your speech from sounding like a series of disconnected points.

Develop the Conclusion

The conclusion of a speech provides a crucial sense of closure, reinforces your central message, and leaves your audience with a powerful and lasting impression. A strong conclusion ensures your presentation feels complete and impactful. To achieve this, it should include four key components:

- Signal the End: You want to clearly signal that your presentation is concluding. Using phrases like, “In conclusion,” “To summarize,” or “Finally” prepares your audience for the end and helps them focus on your final thoughts.

- Summarize the Main Points: Briefly restate your main points, reminding the audience of the key takeaways you covered throughout the presentation. This reinforces their learning and helps the most important information stick.

- Restate the Thesis: Rephrase your core thesis statement in a fresh, impactful way. This isn’t just about repeating yourself; it’s about giving your central message a final, powerful restatement that leaves no doubt about your purpose.

- Memorable Closing Statement: This is your final impression. A strong closing statement should be memorable and provide a sense of completeness. This might involve tying back to your introduction, issuing a clear call to action, offering a final insightful thought, or painting a vivid picture for the audience to leave them thinking about your message long after you’ve finished speaking.

9.4 Develop an Effective Organizational Pattern

The structure of an oral presentation is just as crucial as its content. To ensure clarity and engagement, a speaker must select an organizational pattern that aligns with their purpose and message (Lucas & Stob, 2020). The process begins with creating a detailed outline to organize your content and ensure a logical progression. By mapping out your key messages and supporting materials in a structured format, you create a clear roadmap for yourself and, more importantly, for your audience. A well-constructed outline ensures that your speech is not only informative but also logically structured and easily understood by your audience.

Common Organizational Patterns

There are four common organizational patterns that you can use, each suited for a different purpose. There are four common organizational patterns that you can use, each suited for a different purpose: chronological pattern, problem-solution pattern, cause-effect pattern, and topical pattern. The chronological pattern provides a time-based framework, making it ideal for narratives, historical accounts, or any process that unfolds over time. If your goal is to persuade your audience to adopt a certain course of action, the problem–solution pattern is an excellent choice, as it addresses challenges and proposes actionable solutions (DeVito, 2018). For exploring complex issues, the cause–effect pattern explores the relationships between events and their outcomes, helping the audience understand how one thing leads to another. Finally, the topical pattern divides a subject into distinct categories, allowing for a comprehensive and organized exploration of different facets of a subject (Amelia et al., 2022). By understanding and applying these organizational patterns, speakers can create presentations that are both informative and easily understood.

Chronological Pattern

The chronological pattern presents information in a time-based sequence, following a timeline or progression. This structure is ideal for narratives, historical accounts, or any process that unfolds over time. It can be used to present a sequential flow, where information is arranged in the order it occurred, such as a presentation on the evolution of the internet, starting with its early development and progressing to its current state. The pattern is also process-oriented, making it suitable for explaining how something works or how a process unfolds, such as a presentation explaining the steps to complete a task. Furthermore, it is useful for providing historical context or background information, as seen in a presentation that explains a person’s life. When using this pattern, it is important to ensure clear transitions between time periods and maintain a consistent timeline.

Problem–Solution Pattern

The problem–solution pattern identifies a problem or challenge and then proposes a solution or course of action. It is commonly used in persuasive presentations, proposals, and advocacy speeches. To use this pattern effectively, you should begin with problem identification, where you clearly define the problem, its scope, and its impact, such as a presentation to a school board about the issue of bullying. Next, you present a solution proposal that is viable, explaining its benefits and feasibility, as in a presentation to a company about low employee morale and a plan to improve it. You must then provide justification with evidence and reasoning to support the proposed solution, like a presentation that explains a city’s water supply problem and the solution of building a new water treatment plant. The presentation concludes with a call to action, urging the audience to implement the solution. This pattern works best when the problem is significant and the proposed solution is realistic, relevant, and supported by evidence.

Cause–Effect Pattern

The cause–effect pattern explores the relationship between causes and effects, explaining how certain events or factors lead to specific outcomes. This structure is useful for analyzing complex issues and demonstrating the consequences of actions. An effective cause–effect presentation begins with a cause analysis to identify the underlying reasons for an issue or phenomenon. This is followed by an effect explanation to detail the resulting effects or consequences. Throughout the presentation, you must establish logical connections that clearly link the causes to their effects, and all claims should be evidence-based, supported by credible data and research.

Topical Pattern

The topical pattern divides the topic into distinct subtopics or categories, allowing for a comprehensive and organized exploration of the subject. It is suitable for a wide range of presentations, including informative, persuasive, or overviews. To use this pattern effectively, you should first make a clear sub-topic division by breaking down the topic into logical and mutually exclusive sections. It is important to provide balanced coverage, ensuring that each sub-topic receives adequate attention. The sub-topics should be arranged in a logical sequence, such as in order of importance or complexity. Finally, you must use clear transitions to connect the sub-topics and maintain coherence throughout the presentation, making it easy for the audience to follow your line of thought.

Outlining Your Speech

Once you’ve chosen an organizational pattern, outlining is the essential next step to developing your presentation’s structure. An outline serves as a detailed blueprint for your speech, visually mapping out your introduction, main points, sub-points, supporting materials, and conclusion. It ensures that your ideas are logically ordered, fully developed, and that you stay within your allotted time. Outlining helps you clarify your thinking, identify gaps in your content, and organize complex information into a clear, coherent message.

When preparing a speech, you’ll typically develop at least two types of outlines, each serving a distinct purpose in the preparation process: a simple outline and a detailed outline.

Simple Outline

The simple outline, often referred to as a working or rough outline, is your initial sketch of the speech’s structure. It typically uses keywords or brief phrases to denote main points and perhaps major sub-points.

You use this type of outline primarily during the early stages of brainstorming and organization. It’s designed for quickly mapping out the flow of ideas, testing the logical progression of arguments, and ensuring all major components of the speech are present. It’s less about detail and more about getting the overall shape of the presentation down on paper, allowing for easy rearrangement of ideas. It’s a quick way to ensure your speech has a clear beginning, middle, and end without getting bogged down in specifics.

For a persuasive speech on the benefits of community gardening, for instance, the speaker might use a topical pattern as follows:

- I. Introduction

- II. Environmental benefits

- III. Social benefits

- IV. Economic benefits

- V. Conclusion

Detailed Outline

A detailed outline, also known as a preparation outline or full-sentence outline, is a far more comprehensive and polished version. This outline uses complete sentences for every point, from the thesis statement down to the specific pieces of supporting material. It includes clear labels for each section (introduction, body, conclusion), main points (Roman numerals), sub-points (capital letters), and supporting material (Arabic numerals, lowercase letters, etc.). It often also includes verbal citations for sources.

You use this type of outline when you are ready to fully develop your arguments and ensure logical coherence and sufficient support. It forces you to think through every idea, articulate it clearly, and verify that all evidence directly supports your claims. This level of detail is crucial for thorough preparation, helping to identify any weak points in your argument or areas needing more research. Unlike the simple outline, which is for initial planning, the detailed outline serves as a complete script blueprint, ensuring you have thoroughly prepared every aspect of your message before moving to delivery practice. Below is an example of a detailed outline.

- I. Introduction

- A. Picture an unused city lot transformed into a vibrant green oasis, teeming with fresh produce and bustling with neighbors working side by side.

- B. Urban green spaces, particularly community gardens, directly benefit everyone in a city, not just the gardeners themselves.

- C. My credibility stems from hands-on experience with local garden projects and relevant research into urban agriculture.

- D. Community gardens are vital for urban areas because they offer significant environmental, social, and economic advantages.

- E. Today, we will explore the significant environmental, social, and economic impacts of community gardens.

- II. Main point 1: Environmental benefits

- A. Community gardens significantly improve air quality in dense urban settings.

- 1. Plants absorb airborne pollutants, such as carbon dioxide and particulate matter, which is supported by scientific data from environmental studies.

- 2. By decentralizing food production, plants reduce the overall carbon footprint compared to commercially shipped produce, which requires extensive transportation. B. These green spaces also effectively enhance local biodiversity.

- 3. Community gardens provide essential habitat for crucial local pollinators, such as bees and butterflies, as evidenced by local bee population data from a university study.

- 4. Furthermore, the gardens encourage the cultivation of varied plant species, which actively works against the uniformity of monoculture. C. A third benefit is the reduction of stormwater runoff.

- 5. Garden soil and plants efficiently absorb excess rainwater, which prevents overwhelmed municipal drainage systems, a process clearly illustrated when comparing runoff in paved areas versus green spaces.

- A. Community gardens significantly improve air quality in dense urban settings.

- III. Main point 2: Social benefits

- A. Community gardens are instrumental in fostering strong community cohesion among diverse neighbors.

- B. These green spaces actively promote healthy eating habits by providing access to fresh, affordable produce.

- IV. Main Point 3: Economic benefits

- A. Community gardens directly reduce food costs for all participants by supplementing their grocery budgets.

- B. Establishing and maintaining these gardens also serves to increase surrounding local property values.

- V. Conclusion

- The conclusion will summarize the importance of community gardens and provide a final call to action or thought-provoking statement.

Outline Template

Use the following template as a guide to structure your own presentations. Remember to fill in each section with specific details relevant to your speech.

- I. Introduction

- A. Attention-getter (Hook your audience – story, question, startling fact, quote)

- B. Relevance to audience (Why should they care about this topic?)

- C. Credibility statement (Why are you qualified to speak on this topic?)

- D. Thesis statement (Your main argument or central idea – one clear sentence)

- E. Preview of main points (Briefly state the 2–5 main points you will cover)

- II. Main point 1 (Clear, concise statement of your first main point)

- A. Sub-point (Elaborate on main point 1)

- 1. Supporting material (Examples, statistics, stories, visuals, expert testimony)

- B. Sub-point

- 1. Supporting material

- Transition to main point 2 (Phrase or sentence to move smoothly to the next idea)

- A. Sub-point (Elaborate on main point 1)

- III. Main point 2

- A. Sub-point (Elaborate on main point 2)

- 1. Supporting Material

- B. Sub-point

- 1. Supporting material

- Transition to main point 3

- A. Sub-point (Elaborate on main point 2)

- IV. Main point 3

- A. Sub-point

- 1. Supporting material

- B. Sub-point

- 1. Supporting material

- A. Sub-point

- V. Conclusion

- Signal the end (e.g., “In conclusion,” “To summarize,” “Finally”)

- Summarize main points (Briefly remind the audience of your key takeaways)

- Restate thesis (Rephrase your main argument in a fresh, impactful way)

- Memorable closing statement (Call to action, final thought, tie back to intro, vivid image)

9.5 Incorporate Sufficient Supporting Material and Research

To elevate a presentation from merely informative to truly impactful, speakers must strategically incorporate supporting materials that bolster their message and engage their audience (DeVito, 2018). These materials serve as the backbone of a compelling presentation, providing evidence, context, and visual reinforcement. Statistics and data offer objective proof, grounding claims in factual reality. Examples and stories create relatable connections, illustrating abstract concepts with tangible experiences (O’Hair et al., 2023). Visual aids, such as slides, charts, and videos, enhance understanding and captivate attention, while expert testimony lends credibility, demonstrating that informed authorities endorse the speaker’s points (Anderson, 2024). By carefully selecting and integrating these supporting materials, presenters can craft presentations that are not only persuasive and informative but also memorable and impactful.

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. (April 28 version) [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/ Infographic detailing four types of supporting materials](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/74/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-06-25-001331.png)

Types of Supporting Materials

Statistics and Data

Numbers and data provide objective evidence to support your claims, adding credibility and weight to your messages. Use statistics from reputable sources, such as academic institutions, established research organizations, and government agencies. Ensure that the data is relevant to your topic and directly supports your key messages. Present data in a clear and understandable manner, using charts, graphs, and tables when appropriate. Make sure the data is current, especially when addressing topics that change rapidly over time. Provide context for the data, explaining its significance and implications. Be cautious of using statistics out of context or manipulating data to fit your agenda. An example of using data in a presentation is, “According to a study by the National Institutes of Health in 2025, regular exercise has been shown to reduce the risk of heart disease by 30%.”

Examples and Stories

Examples and stories are a powerful way to bring your message to life, making it more relatable and memorable for your audience. They help people connect with your content on a personal level and can serve as concrete evidence for your points. You can use real-life examples to illustrate your arguments, share personal anecdotes to create an emotional connection, or present case studies to demonstrate the practical application of your ideas. When using these, always make sure your stories and examples are relevant to your topic and audience. Keep them concise and focused to maximize their impact. For example, a lawyer might say, “When I was crossing the street, I saw the defendant drive his car over the center line and cause the accident,” to provide a clear and concise real-life account.

Audio/Visual Aids

Audio/visual aids are supplemental tools that expand the meaning of your verbal delivery, making your message more impactful and memorable. Visuals, such as pictures, or graphs, or words, help your audience create a memorable mental schema that aids in recalling details. Types of visual aids, such as PowerPoint slides, videos, photographs, tables, or figures, can enhance understanding and engagement. For instance, slides can clarify key ideas, while videos can expand the meaning of a concept or demonstrate a process. You can also use physical objects or handouts to create a lasting, tangible impression on your audience.

When choosing your visual aids, it’s crucial to evaluate a few key factors. First, keep them clear, concise, and easy to understand to avoid overwhelming your audience. Focus on impact over quantity and avoid cluttering your slides with too much text. Instead, aim for large, readable fonts and high-quality images. Second, always remember to verbally reference your visual aids during your speech; this connects what your audience sees with what you say and enhances your credibility. Finally, always practice with the specific technology you’ll be using. Confirm internet availability, check audio volume levels, and practice with remote clickers to ensure your presentation runs smoothly.

Expert Testimony

Quoting experts adds credibility and authority to your message, demonstrating that your message is supported by knowledgeable sources. When citing experts who are recognized authorities in their field, ensure that the expert’s testimony is relevant to your topic and supports your key messages. It is important to check the accuracy when citing experts and provide proper attribution. Consider and provide context for the testimony, explaining the expert’s credentials and expertise. Use expert testimony to support your messages but avoid relying on it exclusively. For example, “Dr. Ozwaldo McGhee, a leading researcher in climate science, states that ‘the evidence for climate change is unequivocal.'”

9.6 Understanding Speech Delivery Methods

Effective public speaking involves not only crafting compelling content but also choosing and mastering a delivery method that best suits your purpose, audience, and context. There are four primary ways to deliver a speech: impromptu, manuscript, memorized, and extemporaneous. Each method offers distinct advantages and disadvantages, and understanding them will empower you to make informed choices for your presentations.

Impromptu Speaking

Impromptu speaking involves delivering a speech with little to no preparation ahead of time. You are asked to speak on the spot, reacting to a prompt or question without a prepared outline or script. Its advantages include authenticity, flexibility, and developing critical thinking. It often appears very natural and conversational, as you’re truly thinking on your feet. You can respond directly to the immediate situation, audience questions, or unfolding events. It hones your ability to organize thoughts quickly and articulate them clearly under pressure

However, some of the disadvantages are a lack of structure, increased anxiety, risk of rambling, and potential errors. Speeches can lack logical organization and supporting evidence if not carefully managed. The unpredictability can be very stressful for many speakers. Without preparation, it’s easy to lose focus, repeat points, or go off-topic. Facts might be misstated, or arguments might be less coherent.

Impromptu speaking is best suited for informal situations where spontaneity and quick thinking are valued over detailed precision, like answering a question in a meeting or giving a humorous retort. However, for situations demanding absolute accuracy or formal presentation, a more prepared approach is necessary.

Manuscript Speaking

Manuscript speaking involves delivering a speech by reading directly from a fully written script, thus offering the highest degree of control over your message. Every word is prepared in advance and read aloud. Some of the advantages are precision and accuracy, control over time, and reduced anxiety about content. Manuscript speaking ensures that every word is exact, which is crucial for sensitive topics, legal statements, or highly technical information. It allows for precise timing, as the speech’s length is predetermined. Speakers don’t have to worry about forgetting what to say.

Some disadvantages are a lack of connection, monotonous delivery, limited adaptability, and requiring additional practice. Reading can make it difficult to maintain eye contact and engage authentically with the audience. Speeches can sound flat, robotic, or unnatural, lacking vocal variety and spontaneity. It can be difficult to respond to audience feedback or unexpected events without breaking flow. Manuscript speaking requires practice to sound natural and not just read word for word.

Manuscript speaking is ideal when exact wording is valued, such as delivering a formal policy statement or a news broadcast where every phrase is carefully analyzed. While it guarantees accuracy, it often sacrifices direct audience engagement. This contrasts with methods that prioritize connection, like memorized speaking, which allows for full eye contact but introduces its own set of challenges.

Memorized Speaking

Memorized speaking involves delivering a speech that has been written out word for word and then committed entirely to memory. The speaker recites the speech without notes. Some of the advantages are direct eye contact, polished presentation, and freedom of movement. Memorized speaking allows for maximum eye contact and connection with the audience since no notes are used. A person can appear highly polished and confident if the speech is executed perfectly. It allows for natural gestures and movement without being tied to notes or a podium.

However, some disadvantages are the risk of forgetting, sounding robotic, time-consuming preparation, and a lack of flexibility. Forgetting a line can lead to significant anxiety, long pauses, or a complete breakdown. Like manuscript speaking, memorized speaking can sound unnatural, recited, or lacking in genuine emotion. It requires a significant amount of time and effort to memorize. It can be very difficult to adapt to audience feedback, unexpected interruptions, or time constraints.

Memorized speaking works best for short, impactful presentations like a brief introduction or a perfectly crafted toast where a flawless, uninhibited delivery is desired. However, the high risk of forgetting and the demanding preparation often make it impractical for longer, more complex presentations. For most public speaking situations, a balanced approach that combines preparation with flexibility, like extemporaneous speaking, tends to be the most effective.

Extemporaneous Speaking

Extemporaneous speaking is a powerful and versatile approach in the realm of public speaking, offering a balance between the rigidity of memorized speeches and the unpredictability of impromptu presentations. Extemporaneous speaking involves delivering a presentation from a well-prepared outline, while allowing for flexibility and spontaneity. This method empowers speakers to engage authentically with their audience, fostering a conversational and dynamic atmosphere (Yulanda, 2021). Some of the advantages are authentic engagement, flexibility and adaptability, natural sound, and thorough preparation. Extemporaneous speaking allows for strong eye contact and a genuine connection with the audience, fostering a conversational tone. Speakers can easily adapt their message, examples, or pace based on audience feedback and reactions. It sounds more natural and conversational than reading or reciting, enhancing credibility and rapport. And it encourages in-depth understanding of the material, as you’re speaking from knowledge rather than rote memorization.

Some disadvantages are that extemporaneous speaking requires significant practice, risks of omitting details, potential for wordiness, and requires strong outline skills. Even though a speech is not memorized, it still requires substantial practice to sound smooth and natural. Without a full script, there’s a slight risk of forgetting specific details or statistics. Speakers might use more words than necessary if they haven’t refined their phrasing during practice. Effectiveness heavily relies on the quality and clarity of the prepared outline.

Tips for Extemporaneous Delivery

To master the extemporaneous speaking style, speakers must first prepare an outline that serves as a reliable roadmap, guiding them through their key points (Robinson et al., 2016). Consistent practice is essential to build fluency and confidence, ensuring a smooth and natural delivery. Effective speakers also learn to engage with the audience by maintaining eye contact and adapting to real-time feedback. They use notes sparingly, relying on keywords and phrases rather than full sentences, to keep their focus on connecting with the listeners (Kennedy & Carter, 2016). By embracing these techniques, presenters can unlock the potential of extemporaneous delivery, crafting presentations that are both informative and captivating.

9.7 Apply Effective Nonverbal Communication to Engage the Audience

While the spoken word carries the core message of any presentation, it’s the subtle yet powerful language of nonverbal communication that truly shapes audience perception and connection (Jasuli, 2024). Mastering these unspoken cues is essential for delivering impactful and engaging presentations. This section explores the critical elements of nonverbal communication, beginning with the art of eye contact, a tool for building rapport and conveying confidence (John et al., 2017). We then explore the use of gestures, demonstrating how purposeful and natural movements can enhance your message and add dynamism. Next, we examine the importance of posture, highlighting how standing tall and maintaining a balanced stance projects professionalism and engagement (Azemi, 2021). Finally, we consider the role of facial expressions, emphasizing how genuine and varied expressions can convey emotions and attitudes, creating a deeper connection with your audience (Baccarani & Bonfanti, 2015; Kilag et al., 2023). By understanding and implementing these nonverbal communication techniques, speakers can elevate their presentations and transcend mere information delivery to create truly memorable and impactful experiences.

![Google. (2025) Gemini. [Artificial intelligence system]. https://gemini.google.com/app A presenter is standing with arms open and facing outward](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/74/2025/04/Gemini_Generated_Image_lsw718lsw718lsw7-1024x1024.png)

Key Nonverbal Communication Techniques

Eye Contact

Eye contact (when culturally appropriate) is a powerful tool for establishing a connection and building rapport with your audience. It conveys sincerity, confidence, and engagement. Avoid focusing on one person or section of the audience. Scan the room and make eye contact with different individuals throughout your presentation. In larger settings, focus on making eye contact with people in different sections of the room. Maintain eye contact for a few seconds at a time to show genuine engagement. Be mindful of cultural differences in eye contact norms; in some cultures, prolonged eye contact may be considered disrespectful. Steady eye contact projects confidence and credibility.

Gestures

Natural gestures can amplify your message, emphasize key points, and add dynamism to your presentation. Use gestures that are relevant to your message and add meaning. Open palms, pointing, and clapping for emphasis are examples of purposeful gestures. Use gestures that feel comfortable and authentic; avoid stiff or unnatural gestures. You can use gestures to emphasize important points or highlight key words, and use open gestures, such as open palms, to convey openness and approachability. Ensure that your gestures align with your vocal delivery, and vary your gestures to keep your audience engaged. Avoid fidgeting, playing with objects, or using distracting gestures. Applying purposeful gestures to the correct moment in a speech will strengthen audience engagement.

Posture

Your posture conveys your confidence, professionalism, and engagement. Standing tall and maintaining good posture projects confidence and credibility, while slouching can make you appear nervous, disinterested, or unprofessional. Stand tall, if possible, with your shoulders back and your head up. Maintain a balanced and comfortable stance. Move around the stage or speaking area with purpose and confidence. While maintaining good posture, ensure that you appear relaxed and comfortable. Adjust your posture to the environment. For example, if you are using a podium, stand behind it with good posture. Good posture projects confidence and helps you connect with your audience.

Facial Expressions

Your facial expressions convey your emotions and attitudes. Using appropriate facial expressions can complement your message, engage your audience, and convey sincerity and authenticity. Ensure that your facial expressions align with your message. For example, smile when conveying enthusiasm or use a serious expression when discussing a serious topic. Use genuine and authentic facial expressions. Vary your facial expressions to keep your audience engaged. Also pay attention to your audience’s facial expressions and adjust your content or delivery accordingly. Genuine expressions convey enthusiasm and help create a positive atmosphere.

9.8 Use Effective and Appropriate Language

The power of an oral presentation lies not only in its content but also in the language used to deliver it. Effective language transforms a presentation from a mere transfer of information into a compelling and memorable experience (Amelia et al., 2022). To achieve this, speakers must prioritize clarity and understanding by avoiding jargon and using language tailored to their audience’s understanding. They must also strive for conciseness, eliminating unnecessary words and phrases to ensure their message is direct and impactful (Jean-Pierre et al., 2023). Furthermore, inclusive language is paramount, fostering a welcoming and respectful environment for all listeners (Khorirunisa & Pratama, 2024). Finally, the using effective approaches adds depth and memorability, transforming simple statements into powerful and persuasive messages (Palmer, 2022). By mastering these linguistic techniques, presenters can craft speeches that resonate with their audience, leaving a lasting impression and achieving their intended purpose.

Tips for Effective Language Use

Avoid Jargon

Jargon refers to specialized terms or technical language that may be unfamiliar to a general audience. Tailor your language to your audience’s knowledge level. If they are experts, some jargon may be acceptable. Use jargon sparingly; if you must use jargon, provide clear and concise definitions. Explain complex concepts using analogies or metaphors that are relatable to your audience. When explaining how a computer’s central processing unit (CPU) works, you could say, “Think of the CPU like the brain of your computer. Just as your brain processes thoughts and sends signals to different parts of your body, the CPU processes all the instructions and calculations, telling every other component – from the screen to the keyboard – what to do.” Limit the use of acronyms and explain their meaning on first use. Prioritize clarity and understanding over demonstrating your expertise.

Be Concise

Concise language eliminates unnecessary words and phrases, making your message more direct and impactful. Concrete language, as opposed to abstract language, can help listeners visualize anecdotes and explanations. Abstract words refer to intangible concepts, ideas, or qualities that cannot be perceived directly by the five senses (sight, sound, smell, taste, touch). Examples include “love,” “freedom,” “justice,” and “happiness.” Concrete words refer to tangible objects, specific actions, or sensory details that can be perceived with the five senses. Examples include “red car,” “whispering wind,” “bitter chocolate,” and “rough sandpaper.” Active voice is generally more concise and direct than passive voice. Active voice sounds like this: “The student submitted the assignment on time.” It highlights the actor and emphasizes action. Passive voice sounds like this: “The assignment was submitted on time by the student on time.” It highlights what was done and emphasizes reporting over action. Avoid repeating information or using redundant phrases. Eliminate filler words such as “um,” “like,” and “you know.” Prioritize key messages and eliminate irrelevant information.

Use Inclusive Language

Inclusive language uses terms that intend to not exclude or offend certain groups based on gender, race, ethnicity, sexual orientation, disability, or other characteristics. Use gender-neutral terms (e.g., “folks,” “individuals,” “they”). Avoid language that reinforces stereotypes or perpetuates harmful biases. Use respectful and appropriate language when referring to different groups. Use person-first language when referring to individuals with disabilities. (e.g., “person with a disability” rather than “disabled person”). Be aware of cultural differences and adapt your language accordingly.

9.9 Chapter Summary

Delivering an effective oral presentation requires careful planning, organization, and delivery. This chapter explored the key elements of successful presentations, from identifying your purpose and audience to using supporting materials and engaging nonverbal communication. By applying these strategies, you can manage communication apprehension, connect with your audience, and deliver presentations that inform, persuade, and inspire.

Key Takeaways

- Effective oral presentations require clear purpose, audience awareness, and organized structure.

- Communication apprehension can be managed through practice and preparation.

- Tailor your presentation to the audience, purpose, and situation for maximum impact.

- Use supporting materials, extemporaneous delivery, and nonverbal communication to engage the audience.

- Choose language that is clear, concise, and appropriate for your audience.

Wrap-Up Questions

- Understanding the audience is crucial for tailoring a presentation to resonate with listeners. Chapter 8 discusses the impact of cultural differences on communication. Imagine you are presenting a proposal to a global team with members from both high-context and low-context cultures, and cultures with varying degrees of power distance. How would your audience analysis inform your choice of language and tone (e.g., direct vs. indirect communication, formality) and your approach to supporting material (e.g., reliance on explicit data vs. implied context or relationship-building stories) to ensure your message is effectively received by all?

- The organized structure of a presentation (the introduction, body, and conclusion) is vital for clear communication. Consider the element of confident delivery and its relationship to nonverbal communication (from Chapter 5). How can a presenter’s effective use of eye contact, gestures, and vocalics (from Chapter 8) in the introduction, specifically during the attention-getter and credibility statement, help to immediately build trust and rapport (from Chapter 8) with the audience, setting a positive tone for the rest of the presentation?

- The chapter emphasizes that statistics and data add credibility and weight to a presentation. However, relying solely on numbers might not resonate with all audiences. Thinking about Chapter 8 on cultural differences, specifically high-context vs. low-context cultures, how might an audience from a high-context culture respond differently to a presentation heavily laden with explicit data compared to an audience from a low-context culture? What other types of supporting material (e.g., examples and stories, expert testimony) would be particularly effective in a high-context cultural setting to build trust and rapport (from Chapter 8) and convey meaning implicitly?

- Examples and stories are presented as powerful ways to make a message relatable and memorable. Consider the potential for communication apprehension when a speaker is attempting to share personal anecdotes or sensitive examples. How might a speaker’s negative self-concept (from Chapter 7) make them hesitant to use personal stories, fearing judgment or appearing vulnerable? What strategies for managing nervousness, coupled with a focus on the value of their message, could help a speaker overcome this hesitation and effectively integrate compelling narratives into their presentation?

- The use of audio/visual aids is discussed as a way to increase understanding and engagement. Reflect on the idea of perception of others from Chapter 7, where a speaker’s self-concept can filter how they interpret audience reactions. If a presenter with a fragile self-concept notices subtle cues that suggest audience disengagement (e.g., yawns, averted gaze), how might they misinterpret these nonverbal cues, potentially leading to increased anxiety or a rushed delivery? How could the strategic inclusion and confident explanation of visual aids, combined with a proactive approach to asking clarifying questions (from Chapter 8) to check for understanding, help the speaker to better interpret audience feedback and adapt their presentation effectively?

9.10 Learning Activities

Learning Activity 9.1

Learning Activity 9.2

Learning Activity 9.3

9.11 References

Amelia, D., Afrianto, A., Samanik, S., Suprayogi, S., Pranoto, B. E., & Gulo, I. (2022). Improving public speaking ability through speech. Journal of Technology and Social for Community Service, 3(2), 322-330. http://dx.doi.org/10.33365/jsstcs.v3i2.2231

Anderson, J. T. (2024). Public speaking guidebook: How to speak more assertively and conquer fear. (n.p.).

Azemi, I. (2021). Non-verbal communication in public appearance. International Journal of Arts and Social Science, 4(4), 256-267. https://ijassjournal.com/2021/V4I4/4146585942.pdf

Baccarani, C., & Bonfanti, A. (2015). Effective public speaking: A conceptual framework in the corporate-communication field. Corporate Communications: An International Journal, 20(3), 375-390. http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/CCIJ-04-2014-0025

Beatty, M. J., McCroskey, J. C., & Heisel, A. D. (1998). Communication apprehension as temperamental expression: A communibiological paradigm. Communications Monographs, 65(3), 197-219. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1080/03637759809376448

Brandrick, C., Hooper, N., Roche, B., Kanter, J., & Tyndall, I. (2021). A comparison of ultra-brief cognitive defusion and positive affirmation interventions on the reduction of public speaking anxiety. Psychological Record, 71(1), 109-117. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40732-020-00432-z

Broeckelman-Post, M. A., Hunter, K. M., Westwick, J. N., Hosek, A., Ruiz-Mesa, K., Hooker, J., & Anderson, L. B. (2020). Measuring essential learning outcomes for public speaking. Basic Communication Course Annual, 32(1), 1-28. https://www.academia.edu/65903219/Measuring_Essential_Learning_Outcomes_for_Public_Speaking

Cingi, C. C., Bayar Muluk, N., & Cingi, C. (2023). Analysing your audience in advance. In Improving Online Presentations: A Guide for Healthcare Professionals, 93-103. Springer International Publishing.

DeVito, J. A. (2018). Human communication: The basic course. Pearson.

Grieve, R., Woodley, J., Hunt, S. E., & McKay, A. (2021). Student fears of oral presentations and public speaking in higher education: A qualitative survey. Journal of Further and Higher Education 45(9), 1281-1293. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2021.1948509

Hillmer, L. (2022). Public speaking 101. Phi Kappa Phi Forum, 102(4), 16-17. https://www.proquest.com/scholarly-journals/public-speaking-101/docview/2756273231/se-2

Jasuli, J., Hartatik, S. F., & Astuti, E. S. (2024). The impact of nonverbal communication on effective public speaking in English. Journey Journal of English Language and Pedagogy, 7(2), 226-232. http://dx.doi.org/10.33503/journey.v7i2.834

Jean-Pierre, J., Hassan, S., & Sturge, A. (2023). Enhancing the learning and teaching of public speaking skills. College Teaching, 71(4), 219–226. https://doi.org/10.1080/87567555.2021.2011705

John, A. D., Nagarajan, G., & Arthi, M. (2017). Nonverbal communication in public speaking. Impact Journals, 5(2), 97-100. http://www.impactjournals.us/download/archives/2-11-1488025447-12.ABS%20Hum-NON%20VERBAL%20COMMUNICATION.pdf

Kennedy, J., & Carter, J. (2016). Issue debates: Notecards in extemporaneous speaking. Speaker & Gavel, 53(1), 144-159. https://cornerstone.lib.mnsu.edu/speaker-gavel/vol53/iss1/13/

Kilag, O. K. T., Quimada, G. M., Contado, M. B., Macapobre, H. E., Rabi, J. I. I. A., & Peras, C. C. (2023). The use of body language in public speaking. Science and Education, 4(1), 393-406. https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/the-use-of-body-language-in-public-speaking

Khoirunisa, A., & Pratama, A. C. (2024). Public speaking skills in education in the 21st century: A systematic literature review. Jurnal Edu Aksara, 3(2), 102-120. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.14565774

Lucas, S. E., & Stob, P. (2020). The art of public speaking. McGraw-Hill.

McCroskey, J. C. (1977). Oral communication apprehension: A summary of recent theory and research. Human Communication Research, 4(1), 78–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2958.1977.tb00599.x

McCroskey, J. C. (1984). The communication apprehension perspective. Avoiding communication: Shyness, reticence, and communication apprehension, 13-38. https://archive.org/details/avoidingcommunic0000unse

Munz, S. M., McKenna-Buchanan, T., & Wright, A. M. (Eds.). (2024). The Routledge handbook of public speaking research and theory. Routledge.

O’Hair, D., Rubenstein, H., & Stewart, R. (2023). A pocket guide to public speaking. Macmillan.

Palmer, E. (2022). Speaking out: To prepare students for the real world, schools need a bigger focus on oral communication skills. Education Leadership, 79(8), 64-66. https://ascd.org/el/articles/speaking-out

Raja, F. (2017). Anxiety level in students of public speaking: Causes and remedies. Journal of Education and Educational Development, 4(1), 94-110. http://dx.doi.org/10.22555/joeed.v4i1.1001

Robinson, T. M., Clemens, C. M., & Ortega, S. (2016). The evolution of extemporaneous speaking: A structuration approach. Forensic, 101(1), 21-29.

Scott, J. W., Robertson, M., & Tatum, N. T. (2024). Audience analysis in public speaking: A comprehensive exploration. In The Routledge Handbook of Public Speaking Research and Theory, 91-99. Routledge.

Seiler, W., Beall, M., & Mazer, J. (2021). Communication: Making connections. Pearson.

Thompson, N. (2024). Public speaking struggles for technical professionals. Talent Development, 78(6), 20-22. https://www.td.org/content/td-magazine/public-speaking-struggles-for-technical-professionals

Yulanda, N. (2021). The implementation of the effective strategy for practicing extemporaneous speech style in public speaking. English Language Teaching, Applied Linguistic and Literature, 2(2), 63-70. https://www.sciencegate.app/source/660911825

Zarefsky, D., & Engels, J. D. (2021). Public speaking: Strategies for success. Pearson.

Images:

Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/

“Comm_Apprehension” by Nic Ashman, Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. (June 6 version) [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/

“pexels-ron-lach-9786061” by Ron Lach, via Pexels is licensed under CC0

Google. (2025) Gemini. [Artificial intelligence system]. https://gemini.google.com/app

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. (June 6 version) [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/

The content of an effective presentation is meticulously planned, focused, and well-supported, ensuring that the message is clear, credible, and compelling to the audience.

A clear purpose acts as the compass for your entire presentation. It ensures that every element aligns with a specific goal, whether to inform, persuade, or entertain.

Beyond the content itself, the way a presentation is delivered significantly impacts its effectiveness. These elements pertain to the speaker’s performance and use of aids.

Supplemental information that expands the meaning of the verbal delivery. Words, pictures, graphs, and more can emphasize the impact of the message and make it more memorable.

An individual's fear or anxiety associated with real or anticipated communication with another person or persons. Often referred to as "stage fright" in the context of public speaking, communication apprehension can manifest in various forms. Symptoms can range from mild nervousness to severe panic, impacting a speaker's ability to prepare, deliver, and engage effectively with their audience.

A psychological pattern in which an individual doubts their accomplishments and has a persistent, internalized fear of being exposed as a "fraud," despite external evidence of their competence and success. In the context of public speaking and communication, someone experiencing imposter syndrome might feel that their knowledge, skills, or even their right to speak on a topic are insufficient, even when they are objectively well-prepared and capable.

Any information used in a speech or presentation to illustrate, clarify, prove, or add interest to the speaker's main points and arguments. Effective supporting material helps to make a message more credible, understandable, and memorable for the audience.

Involves using clear signals like “First,” “Second,” or “Finally.” These simple verbal cues help organize your thoughts and provide a clear roadmap for your audience.

Also known as a preparation outline or full-sentence outline, a detailed outline is comprehensive and polished. This outline uses complete sentences for every point, from the thesis statement down to the specific pieces of supporting material.

A method of organizing a speech or presentation where the main points are arranged in a sequential order based on time. This pattern is particularly effective for explaining historical events, processes, or step-by-step instructions, allowing the audience to follow the progression of information clearly.

A method of organizing a speech or presentation that structures the main points around identifying an issue and then proposing a remedy.

Explores the relationship between causes and effects, explaining how certain events or factors lead to specific outcomes.