Chapter 5: Interpersonal Conflict Management

5.0 Introduction

Learning Objectives:

- Define conflict clearly using nonjudgmental language

- Identify and apply conflict management strategies

- Use assertive verbal and nonverbal behaviors effectively

- Analyze the effectiveness of conflict management strategies

Conflict, an inevitable aspect of human interaction, stems from differences in opinions, values, or goals. However, effective communication transforms conflict from a challenge into an opportunity for growth, understanding, and stronger relationships. This chapter will explore strategies for analyzing, managing, and resolving conflict, focusing on how to clearly articulate conflict issues, employ appropriate communication styles, utilize assertive communication techniques, and evaluate the communication effectiveness of your approach. By the end of this chapter, you will possess the communication skills necessary to navigate conflict constructively in both personal and professional settings.

View the following supplementary YouTube video to learn more: How Understanding Conflict Can Help Improve Our Lives | Robin Funsten | TEDxTryon

A Short Story: The Team That Turned Conflict into Collaboration

A marketing team, tasked with launching a new product, quickly encountered conflict due to contrasting communication styles and differing visions. Alina, the project lead, used a direct communication approach, advocating for a traditional advertising campaign without fully exploring alternative perspectives. Terrick, a creative team member, employed a more assertive communication style, pushing for a bold, unconventional approach, often dismissing traditional methods. This communication breakdown led to escalating disagreements, missed deadlines, and a tense work environment. Realizing the detrimental impact of the conflict, Alina began a meeting focused on open and empathetic communication. She facilitated active listening, encouraged everyone to articulate their perspective without judgment, and worked with the team to establish a collaborative communication framework for finding a mutually agreeable compromise. By integrating elements of both approaches through clear and respectful dialogue, the team worked together more smoothly, resulting in a successful campaign that satisfied everyone.

This story highlights the importance of effective communication in managing conflict. In this chapter, we will explore how to define conflict through clear communication, identify communication-based strategies for resolution, and apply these strategies to real-life situations.

5.1 Understand Conflict: Why We Engage

The Nature of Conflict

Conflict is an inevitable and often necessary aspect of human interaction. People engage in interpersonal conflict when they perceive that their goals, needs, or values are incompatible with those of others. This clash can stem from limited resources, differing perspectives, or contrasting priorities about how a situation should unfold. Even in everyday life, conflict can arise from something as small as disagreements over chores, disputes about leisure plans, or unmet expectations within relationships. At its core, conflict is defined by the perception that one person’s goals are being blocked by another, making it a central feature of both personal and professional communication (Odell et al., 2004).

Conflict in the Workplace

In the workplace, conflict often mirrors the dynamics of interpersonal disagreements but becomes more complex because of organizational structures, hierarchical roles, and professional pressures. Workplace conflict can emerge from unclear expectations, high-stress environments, or competing departmental objectives. It may take the form of procedural conflict, which occurs when group members disagree about the methods or processes to achieve a goal, such as deciding how to select a topic or organize workflow. A substantial conflict arises when the disagreement centers on the actual content of the task, as when team members debate which project should take priority or what solution best addresses a problem. Interpersonal conflict, by contrast, focuses on clashes rooted in individual values, goals, or relationships. For example, in a restaurant setting, a server may believe a cook is not preparing meals adequately, while the cook may feel the server is failing to communicate orders clearly. These examples highlight how both personal and structural factors combine to shape the conflicts that occur in organizational life (Bettencourt & Sheldon, 2001; Chun & Choi, 2014; Hinsz & Robinson, 2025).

Styles of Conflict Management

Because conflict is so deeply connected to communication, navigating it effectively requires an understanding of different approaches to managing disagreements. The way individuals choose to communicate during conflict not only influences the immediate outcome but also affects the long-term health of relationships. Research identifies five broad styles for conflict management, each rooted in distinct communication patterns: avoiding, accommodating, competing, compromising, and collaborating (Braithwaite & Schrodt, 2017; Southwest Tennessee Community College, 2020; Wrench et al., 2020). These styles vary in their emphasis on personal goals versus the needs of others and provide a framework for selecting communication behaviors that align with specific contexts. For the purpose of this and the following section, strategies and styles will be used interchangeably. The reasoning for this is that within certain literature they are described one way in in others another, however, the concepts remain exactly the same.

The Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument

One of the most widely used tools for examining conflict management is the Thomas-Kilmann Conflict Mode Instrument (TKI), developed by Kenneth Thomas and Ralph Kilmann. This framework categorizes conflict-handling styles along two dimensions: assertiveness, which reflects the degree to which individuals pursue their own needs, and cooperativeness, which reflects the degree to which they seek to satisfy the needs of others (Thomas, 2008). Together, these dimensions create a grid that identifies five conflict modes corresponding to the previously noted styles of avoiding, accommodating, competing, compromising, and collaborating. By situating conflict management within this model, the TKI clarifies why people tend to favor certain approaches and how these preferences can shift depending on the situation.

Assertiveness and Cooperativeness in the TKI Grid

The grid of the TKI model has vertical and horizontal axes. The vertical axis measures assertiveness, reflecting the extent to which an individual works to satisfy their own concerns. At the high end, assertiveness can manifest as aggression, often seen in the competing mode, where individuals pursue their own interests regardless of the cost to others. At more moderate levels, assertiveness reflects a balanced ability to stand up for one’s needs while maintaining respect for the other party. At the low end, passivity emerges, leading individuals to neglect their own needs and withhold their perspectives. The horizontal axis represents cooperativeness, or the degree to which an individual attempts to meet the concerns of others. Low cooperativeness results in avoidance or disregard for the other’s needs, while higher levels involve efforts to seek common ground or support the interests of others. At its extreme, this may result in over-accommodation, where an individual sacrifices their own needs repeatedly to maintain harmony, even at personal cost.

The Five Conflict Styles

Assertiveness and cooperativeness combine to form the five conflict styles, each of which represents a distinct approach to managing disagreements (Turner et al., 2020). Competing, also known as forcing, is high in assertiveness and low in cooperativeness, focusing on achieving one’s own goals, sometimes aggressively, at the expense of others. Accommodating, or yielding, reverses this dynamic, placing the needs of others above one’s own, often to preserve harmony or relationships. Avoiding, or withdrawing, reflects low levels of both assertiveness and cooperativeness, often leaving issues unresolved but useful in trivial or temporary circumstances. Collaborating, sometimes referred to as problem-solving, combines high assertiveness with high cooperativeness, seeking creative, win-win outcomes that satisfy all parties involved. Finally, compromising, sometimes referred to as give-and-take, balances moderate levels of both dimensions, encouraging each party to give up something to reach a mutually acceptable, if imperfect, resolution. Together, these strategies illustrate the complexity of conflict and the many communicative choices individuals can make when facing it.

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. (April 28 version) [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/ Infographic detailing five conflict styles](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/74/2025/04/Conflict-Styles-1024x685.png)

The Role of Context in Conflict Management

The TKI model underscores that no conflict mode is inherently superior; instead, effectiveness depends on context, the relationship between the individuals involved, and the stakes of the issue. Avoidance might be appropriate when the matter is trivial or when emotions are too high to allow for productive discussion, while collaboration is most effective for complex challenges that require innovative solutions and mutual commitment. Competing may be necessary when quick, decisive action is needed, while accommodating can preserve harmony when maintaining the relationship is more important than the outcome of the disagreement. Compromise, though often leaving both parties partially unsatisfied, provides a practical middle ground when time or resources are limited. By becoming aware of their own tendencies and learning how to adapt, individuals can manage conflict in ways that resolve disputes while also preserving, and sometimes strengthening, their relationships.

5.2 Define the Conflict Clearly, Using Nonjudgmental Language

Navigating interpersonal conflict requires a careful balance of assertiveness and empathy (Brule & Eckstein, 2019; Egbe, 2024). To foster constructive dialogue and encourage resolution, it is important to define conflicts using nonjudgmental language (Jit et al., 2016). This approach ensures that the focus remains on the problem itself rather than on personal attacks or generalized statements, which often escalate tension. By framing conflicts in clear, respectful, and specific terms, individuals create opportunities for collaboration and mutual understanding. The following strategies illustrate how conflicts can be defined productively, setting the stage for resolution that addresses concerns without undermining relationships.

Focus on the Issue, Not the Person

One of the most effective strategies is to separate the conflict from the individual involved is focus on the issue, not the person. Addressing specific behaviors or situations rather than criticizing the person prevents defensiveness and reduces the likelihood of emotional escalation. When attention is placed on the problem itself, the dialogue shifts toward collaboration and problem-solving. This strategy aligns closely with the collaborating conflict style, which emphasizes finding solutions that benefit everyone. For example, instead of saying, “You don’t listen to my ideas; you are so dismissive,” a clearer and less confrontational approach would be, “I’ve observed that my proposed solutions are not being discussed in depth, and I feel that my contributions are not being fully considered.” Such language acknowledges the issue without attacking the person, keeping the door open for constructive dialogue.

Use “I” Statements

Another important strategy involves using “I” statements to express personal feelings and experiences without placing blame on others. These statements shift the responsibility away from accusing language and instead demonstrate ownership of one’s own emotions. This practice reduces defensiveness and fosters an environment where the other party is more likely to listen and respond with empathy. The technique fits well with accommodating and compromising conflict styles, which emphasize preserving relationships and seeking balance. A practical formula is: “I feel [emotion] when [specific behavior or situation occurs] because [impact on you].” For example, rather than saying, “You often miss deadlines, and you do not care about the team,” one might say, “I feel frustrated and concerned when deadlines are missed because it affects the team’s progress and increases my workload.” In this way, the issue is clearly defined while still maintaining respect for the relationship.

Avoid Generalizations

Conflict can also be more effectively defined by avoiding sweeping generalizations such as “always” or “never.” These exaggerations tend to oversimplify the problem, making it appear insurmountable and fostering defensiveness. By focusing on specific examples, the conversation becomes grounded in reality, and the problem is easier to address. This approach is consistent with compromising and collaborating styles, which rely on concrete information to develop workable solutions. For example, instead of saying, “You are always late and inconsiderate,” a more constructive statement would be, “I noticed you were late to the last three team meetings: on Monday, you arrived 15 minutes late; on Wednesday, you were 10 minutes late; and today, Friday, you were 20 minutes late.” By providing specific instances, the discussion remains focused and productive rather than accusatory.

Clarify the Impact

Clarifying the impact of a conflict allows others to see the real consequences of their actions, encouraging accountability and shared responsibility. Explaining how the issue affects an individual or the group fosters empathy and creates motivation to find solutions. This strategy closely aligns with collaborating, as it emphasizes open communication and mutual understanding, but it can also serve compromising approaches by highlighting the importance of finding middle ground. For example, saying, “When communication is unclear, it delays my work because I have to spend extra time seeking clarification, which creates confusion for the entire team and can push back project deadlines,” identifies both the problem and its broader implications. By focusing on the outcomes of behavior, this strategy helps all parties recognize the importance of resolution.

5.3 Apply Conflict Management Strategies to a Real or Simulated Conflict Situation

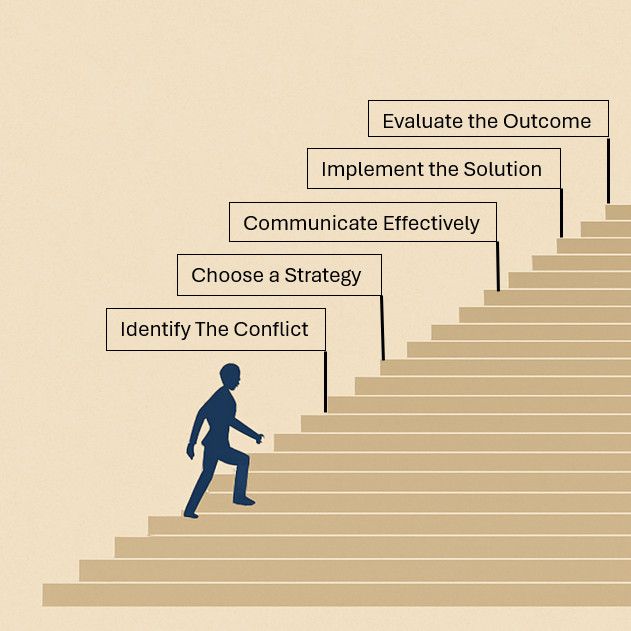

Effectively navigating conflict requires a communication-focused and structured approach. By following a series of deliberate communicative steps, individuals can increase their chances of reaching a favorable resolution (Hample & Richards, 2019; Hategan, 2020). This section outlines a five-step process for applying conflict management strategies. First, clearly identify the conflict using nonjudgmental communication. Second, choose the most appropriate communication approach based on the situation. Third, communicate effectively with assertive verbal and nonverbal behaviors. Fourth, implement the agreed-upon solution and define communicative next steps. Finally, evaluate the communication outcome to learn and adapt for future conflicts. This framework provides a practical guide for transforming potentially damaging disagreements into opportunities for understanding and growth through effective communication.

Five Steps for Applying Conflict Resolution Strategies

Whether it’s a disagreement over project deadlines, differing approaches to problem-solving, or personality clashes, the ability to manage conflict constructively is an essential professional skill. The following steps provide a structured, effective process for addressing workplace conflicts in a way that promotes cooperation, productivity, and mutual respect.

Step 1: Identify the Conflict

The first step in resolving any conflict is to understand exactly what it is about. This means going beyond the immediate disagreement to uncover the deeper needs, concerns, and perspectives of everyone involved. A clear, nonjudgmental description of the conflict helps prevent defensive reactions and keeps emotions from escalating. For example, two coworkers might disagree over who should lead a client presentation. At first, it appears to be a matter of ambition or preference, but after discussion, it becomes clear that one is eager to showcase their skills for a promotion, while the other has long-standing rapport with the client and feels best positioned to maintain that relationship. Understanding these underlying concerns allows for a resolution that respects both interests.

Step 2: Choose a Strategy

Once the conflict is clearly defined, the next step is deciding how to address it. There is no single “best” approach; the strategy should fit the circumstances. Factors to consider include the seriousness of the issue, the importance of the working relationship, the time available, and whether there are any power imbalances. For instance, if two departments are clashing over the allocation of budget resources, and the decision needs to be made quickly to meet a quarterly deadline, a temporary compromise may be necessary. However, if the issue will affect long-term operations, a more collaborative approach – bringing all stakeholders together to develop a sustainable plan – may be the better choice.

Step 3: Communicate Effectively

Communication is at the heart of resolving conflict. This involves stating your perspective clearly and respectfully, while also listening to fully understand the other person’s point of view. Assertive communication – being honest and direct without being aggressive – creates a constructive dialogue. Consider a project manager frustrated that a team member keeps missing deadlines. Saying, “You’re slowing down the whole team,” is likely to create defensiveness. Instead, the manager might say, “I’m concerned that the missed deadlines are affecting our ability to deliver on time. Can we talk about what’s causing the delays?” This frames the issue around the impact of the behavior rather than making personal accusations, opening the door for problem-solving.

Step 4: Implement the Solution

Once a strategy is chosen and communication has clarified expectations, it’s time to put the solution into action. This often involves agreeing on specific responsibilities, timelines, and follow-up steps. A clear plan ensures everyone understands their role in resolving the conflict. For example, two marketing specialists who have been stepping on each other’s responsibilities might agree that one will take the lead on social media campaigns while the other focuses on email marketing. They set up a bi-weekly meeting to coordinate efforts and avoid future overlap. By defining roles clearly, they prevent similar conflicts from arising.

Step 5: Evaluate the Outcome

Finally, it’s important to assess whether the resolution was effective. Did it solve the problem? Are all parties reasonably satisfied? What worked well in the process, and what could be improved? A manager who mediated a dispute between two team members might check in after a month to see if the agreed-upon changes are working. If not, adjustments can be made – perhaps by providing additional resources, setting clearer deadlines, or revisiting workload distribution. This evaluation ensures that solutions remain effective over time and reinforces a culture of continuous improvement.

By identifying the conflict, choosing an appropriate strategy, communicating effectively, implementing a clear solution, and evaluating the outcome, workplace conflicts can become opportunities for improved teamwork and stronger professional relationships. When addressed with respect and openness, conflict can lead not only to resolution but also to growth – for individuals, teams, and the organization as a whole.

Real-World Application

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. (April 28 version) [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/ Two people are crouched down testing soil in a field](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/74/2025/04/ChatGPT-Image-Jun-6-2025-01_50_34-PM.png)

Two siblings, Amara and Mateo, inherited a family farm. Amara wants to transition a portion of their shared field to sustainable cover cropping for long-term soil health, potentially reducing immediate yield, while Mateo prefers traditional methods to maximize current crop production.

First, to identify the conflict, Amara initiates a conversation, saying, “Mateo, I feel concerned about the long-term health of our soil if we don’t adopt more sustainable practices, and I’m worried about future yields.” Mateo responds, “I understand your concern for the soil, but I’m worried about our income this season if we cut back on our usual crops.” This clarifies their differing priorities.

Next, they choose a strategy, recognizing the importance of both soil health and immediate income, they opt for a collaborative approach to find a solution that respects both needs. They then communicate effectively, with Amara explaining the benefits of cover crops for soil structure and nutrient retention, and Mateo sharing detailed figures on expected revenue from traditional crops. They actively listen to each other and ask clarifying questions. Together, they implement the solution, agreeing to trial cover crops on a smaller, designated section of the field while maintaining traditional methods on the rest, and they define a clear timeline for assessing the results. Finally, at the end of the harvest season, they evaluate the outcome by comparing soil test results and yields from both sections, learning valuable insights that will inform their land-management decisions for future planting seasons. This process allowed them to transform a potential family dispute into a shared learning experience that benefited the farm.

5.4 Use Assertive Verbal and Nonverbal Behaviors Effectively

Effective assertive communication relies on a combination of both verbal and nonverbal cues. Assertive verbal cues involve using clear and direct language to state your position, actively listening to understand others’ perspectives, and maintaining a calm and respectful tone (Egbe, 2024; Hample, 2018; Jit et al., 2016). Assertive nonverbal cues include maintaining appropriate eye contact to show engagement and confidence, using open body language to signal receptiveness, controlling tone of voice to remain calm and respectful, and employing gestures appropriately to emphasize points without aggression. By mastering both verbal and nonverbal assertive behaviors, individuals can effectively express their needs and perspectives while fostering productive and respectful interactions.

Verbal Behaviors

Assertive communication starts with clear and direct language to state your position honestly, avoiding vagueness that can be misinterpreted (Egbe, 2024; Hample, 2018; Jit et al., 2016). This means using “I” statements to express your perspective, being specific about your needs, and avoiding hedging words like “maybe” or “I think.” For instance, instead of saying, “I need help with this project,” a more effective approach is, “I need you to review the data analysis section of the Q3 report by 3 p.m. today so I can finalize the presentation slides.” Another key verbal behavior is staying calm and respectful to prevent a conflict from escalating. This means monitoring your emotions, using a steady tone, and choosing your words carefully to avoid accusatory language. This approach ensures your message is heard and understood, reducing the likelihood of misunderstandings and promoting a more productive conversation.

In addition to direct language, effective assertive communication requires listening to and confirming the other person’s message (Egbe, 2024; Hample, 2018; Jit et al., 2016). Active listening shows that you value the other person’s perspective. It involves engaging with what’s being said by paraphrasing their ideas and asking clarifying questions. For example, you might say, “So, you’re saying you need more time to gather data?” to confirm your understanding. Simultaneously, using confirming messages – verbal cues that express value and appreciation – validates the other person’s feelings and right to speak. This includes simply acknowledging their presence and their attempt to communicate. Both active listening and confirming messages build trust, demonstrate respect, and ensure you fully understand the other person’s perspective.

It’s also essential to be aware of and avoid disconfirming messages, which invalidate the other person and create a hostile environment. These messages, identified by Dr. John Gottman (1999) as the “Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse,” include criticism (disapproval of someone or something based on perceived faults or mistakes), stonewalling (refusing to engage), defensiveness (behavior intended to defend or protect), and contempt (disrespectful behavior like sarcasm or eye-rolling). Gottman and Silver (1999) found that the consistent presence of these four communication behaviors is a strong predictor of relationship dissolution. Recognizing and avoiding these behaviors is crucial because they erode trust, escalate conflict into personal attacks, and prevent any possibility of a productive resolution.

Nonverbal Behaviors

Assertive communication also depends heavily on your nonverbal cues, which can either reinforce or undermine your message (Egbe, 2024; Hample, 2018; Jit et al., 2016). Maintaining eye contact shows you are engaged and confident in your position, but it’s important to be mindful of cultural norms and avoid a stare that could be seen as aggressive. Using open body language, such as an upright posture and relaxed shoulders, signals that you are receptive and willing to engage, rather than defensive. Similarly, controlling your tone of voice is critical. Speaking calmly and respectfully conveys composure, even when discussing difficult topics, and prevents the conflict from escalating. Finally, using gestures appropriately can emphasize your points and add clarity to your message. However, gestures should be natural and purposeful, avoiding aggressive or distracting movements like pointing fingers. Together, these nonverbal behaviors create a more positive and collaborative environment, making it easier to have a constructive conversation and build rapport.

5.5 Analyze the Effectiveness of Conflict Management Strategies

Analyzing the communicative effectiveness of conflict management strategies is crucial for continuous improvement and ensuring that conversations around differing opinions are truly productive (McElearney, 2023). This final section identifies techniques for evaluating the success of communication in conflict management efforts (Hample, 2018). By reflecting on the communication process, seeking feedback from others, assessing the communicative outcome, and identifying lessons learned, individuals and teams can gain valuable insights into what communication approaches work well and what communication adjustments can be improved when navigating interpersonal conflicts (Pizzo et al., 2025). This communication-centered, analytical approach transforms each conflict into a communication learning opportunity, fostering more effective and sustainable conflict management practices.

Techniques for Analysis

Reflect on the Process

Simply resolving a conflict on the surface isn’t enough; true effectiveness comes from addressing the underlying issues that fueled the disagreement. Reflecting on the process involves examining whether the chosen conflict management strategy went beyond just treating the symptoms and truly tackled the root cause. This requires looking back at the initial disagreement, analyzing the strategy used (avoiding, accommodating, competing, compromising, or collaborating), and considering the key interactions to determine if the outcome truly addressed the core problem and went beyond a temporary fix. For instance, if collaboration was used, you should consider whether the process involved genuine dialogue that led to a solution satisfying the core needs of both parties, or if it was a superficial agreement. This type of reflection helps ensure the resolution is sustainable and prevents the recurrence of similar conflicts.

Seek Feedback

Your own perception of how a conflict was handled might be biased, so it’s vital to seek feedback from others involved. This provides valuable insights into the effectiveness of the chosen strategy and your own performance. Different people may have observed aspects of the conflict or the resolution process that you overlooked, offering a more comprehensive understanding of what worked well and what could be improved. To implement this, identify key stakeholders and ask them specific, targeted questions like, “Did you feel heard and understood?” or “What could have been done differently?” It’s essential to be prepared to receive constructive criticism and create a safe space for open and honest responses. This feedback provides a more objective assessment and helps you identify areas for both personal and collective improvement in handling future conflicts.

Assess the Outcome

The ultimate measure of a conflict resolution strategy’s effectiveness is whether it achieved the desired results. Assessing the outcome involves evaluating the tangible and intangible results of the resolution, and it requires looking at both short-term and long-term effects. To do this, you must first identify the desired outcome: what were you hoping to achieve? Then, measure the results by looking at tangible indicators of success, such as whether the problem was resolved or deadlines were met. It is also important to consider any unintended consequences and evaluate whether the resolution created a lasting solution or if the conflict is likely to resurface. For example, if the conflict was about a project deadline, you should assess whether the revised deadline was met without further issues and if the team’s morale or productivity was affected.

Identify Lessons Learned

Every conflict resolution experience offers an opportunity for learning and growth. Identifying lessons learned involves reflecting on both the successes and failures of the process. You can do this by reviewing the entire process, from identifying the conflict to assessing the outcome, and noting what aspects of the strategy or your actions were particularly effective. Similarly, you should identify areas where things could have been done differently to achieve a better outcome. It is helpful to document key takeaways so they can be referenced in the future and to share these insights with others to improve the overall conflict management capabilities of the team or organization. For example, a key lesson learned might be: “Next time, we should clarify roles and responsibilities at the start of the project to avoid similar conflicts over workload distribution.”

Real-World Application

5.6 Chapter Summary

Conflict is a natural part of human interaction, but it can be managed effectively with the right strategies. This chapter explored how to define conflict clearly, identify and apply conflict management strategies, use assertive communication, and evaluate the effectiveness of your approach. By mastering these skills, you can navigate conflict constructively, build stronger relationships, and achieve positive outcomes in both personal and professional settings.

Wrap-Up Questions

- The chapter states that conflict is “inevitable and often necessary.” Think about a past conflict you’ve experienced, personal or professional, that, after it was resolved, led to a positive outcome (e.g., improved understanding, a better process, stronger relationship). What made that particular conflict “necessary,” and how did engaging with it lead to a better result?

- The chapter outlines five conflict styles. Consider a situation where you or someone you know typically defaults to the avoiding (withdrawing) style. What are the potential short-term advantages of this style in that specific context, and what are the more significant long-term disadvantages for both the individual and the relationship or group involved?

- The text emphasizes that clear and direct language is fundamental to assertive verbal behavior, particularly through “I” statements and avoiding hedging. Imagine a situation where you need to deliver constructive criticism to a peer. Draft two versions of your feedback: one using vague language and hedging, and another using clear, direct “I” statements. How would the likely reception and impact of these two messages differ, and why is the assertive version more effective?

5.7 Learning Activities

Learning Activity 5.1

Learning Activity 5.2

Learning Activity 5.3

5.8 References

Braithwaite, D., & Schrodt, P. (2017). Engaging theories in interpersonal communication: Multiple perspectives. Routledge.

Brule, N. J., & Eckstein, J. J. (2019). “NOT My Issue!!!”: Teaching the interpersonal conflict course. Journal of Communication Pedagogy, 2, 17–22. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/jcp/vol2/iss1/5/

Bettencourt, B. A., & Sheldon, K. (2001). Social roles as mechanisms for psychological need satisfaction within social groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 1131. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11761313/

Chun, J. S., & Choi, J. N. (2014). Members’ needs, intragroup conflict, and group performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(3), 437. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036363

Egbe, J. A. (2024). The impact of effective communication in conflict resolution: A case study of Agbani/Nkerefi conflict. Oracle of Wisdom Journal of Philosophy and Public Affairs, 8(3), 147–158. https://www.acjol.org/index.php/owijoppa/article/view/6047

Gottman J, & Silver N (1999). The Seven Principles for Making Marriage Work. New York, NY: Crown Publishers.

Hample, D. (2018). Interpersonal arguing. Peter Lang Verlag. https://doi.org/10.3726/b12877

Hample, D., & Richards, A. S. (2018). Personalizing conflict in different interpersonal relationship types. Western Journal of Communication, 83(2), 190–209. https://doi.org/10.1080/10570314.2018.1442017

Hategan, V. (2020). Communication perspectives in mediation and conflict resolution. International Journal of Communication Research, 10(3), 303–308. https://www.ijcr.eu/articole/512_008%20Vasile%20Hategan.pdf

Hinsz, V. B., & Robinson, M. D. (2025). A conceptualization of mood influences on group judgment and decision making: The key function of dominant cognitive processing strategies. Small Group Research, 56(1), 71–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/10464964241274124

Jit, R., Sharma, C. S., & Kawatra, M. (2016). Servant leadership and conflict resolution: A qualitative study. International Journal of Conflict Management, 27(4), 591–612. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJCMA-12-2015-0086

McElearney, P. (2023). A performative and dialogic approach to teach group roles, group conflict, and conflict management styles. Communication Teacher, 37(3), 227–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/17404622.2023.2168714

Odell, J., Nodine, M., & Levy, R. (2004). A metamodel for agents, roles, and groups. In International Workshop on Agent-Oriented Software Engineering (pp. 78–92). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-30578-1_6

Pizzo, M., Terrance, S., & Abu-Ras, W. (2025). Online project-based learning in small groups: Innovative approaches to leadership development for social work students. Social Work With Groups, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2025.2454023

Thomas, K. W. (2008). Thomas-kilmann conflict mode. TKI Profile and Interpretive Report, 1(11).

Turner, W., Coleman, L., & King, T. (2020). Competent communication, 2e. Southwest Tennessee Community College. https://socialsci.libretexts.org/Courses/Southwest_Tennessee_Community_College/Competent_Communication_-_2e

Wrench, J. S., Punyanunt-Carter, N. M., & Thweatt, K. S. (2020). Interpersonal communication: A mindful approach to relationships. Milne Open Textbooks. https://milneopentextbooks.org/interpersonal-communication-a-mindful-approach-to-relationships/

Images:

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. (April 28 version) [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/

“Thomas_Kilmann_conflict_mode_instrument” by Ghilt is licensed under CC0, Public Domain

“Applying_strategies” by Nic Ashman, Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. (April 28 version) [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/

Videos:

TEDx Talks. (2016, October 19). How Understanding Conflict Can Help Improve Our Lives | Robin Funsten | TEDxTryon [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=fdDQSHyyUic

An inevitable aspect of human interaction, conflict stems from differences in opinions, values, or goals.

Conflict that occurs when group members disagree about the methods or processes to achieve a goal.

Conflict that focuses on clashes rooted in individual values, goals, or relationships.

The extent to which an individual attempts to satisfy their own concerns in a conflict.

The extent to which an individual attempts to satisfy the concerns of the other person involved in the conflict.

The habitual patterns of behavior and communication strategies that individuals tend to employ when confronted with disagreements, opposition, or perceived threats to their interests.

Asserting your position at the expense of others.

Communication that prioritizes the other party’s needs over your own.

Ignoring or withdrawing from conflict.

Working together to find a win–win solution.

Finding a middle ground where both parties give up something.

This strategy emphasizes separating the problem from the individual involved.

Statements that shift the focus from assigning blame to taking ownership of your own experience.

A general statement or concept obtained by inference from specific cases.