Chapter 4: Leadership and Teamwork Skills

4.0 Introduction

Course Competency: Develop teamwork and collaboration skills

Learning Objectives:

- Participate effectively in group interactions

- Recognize and address negative group behaviors

- Evaluate the process of group interactions

- Analyze decision-making strategies used by groups

- Understand task, maintenance, and leadership roles in group dynamics

Effective teamwork and collaboration hinge on clear, consistent, and adaptable communication. Whether completing a group project, participating in a team meeting, or collaborating on a community initiative, understanding and utilizing strategic communication is important for success. A group is typically defined as a collection of more than two people who interact with each other over time, share a common purpose or goal, and perceive themselves as a distinct unit. As students, you will participate in group projects, offer feedback in focus groups, and manage conflict within discussion groups. This chapter examines the fundamentals of teamwork, explicitly highlighting how communication shapes group roles, facilitates effective participation, addresses disruptive behaviors, informs process evaluation, and influences decision-making strategies. By the end of this chapter, you will possess the communication tools necessary to contribute meaningfully to any group and cultivate a truly collaborative environment.

A Short Story: The Team That Couldn’t Agree

A team of five colleagues, tasked with developing a marketing campaign for a new product, possessed diverse skills but lacked effective communication, hindering their collaboration. The project lead, Jillian, resorted to unilateral decision-making, feeling unheard and unable to facilitate open dialogue. A creative thinker, Jonas dominated meetings with unrefined ideas, demonstrating poor listening and a lack of follow-through. The organizer, Maria, struggled to communicate her attempts to structure the project, leading to her feeling ignored. Meanwhile, Alex and Priya, the quieter members, withheld valuable insights due to a lack of encouragement and channels for their input. Consequently, the team missed deadlines, and their final campaign lacked cohesion. What went wrong? The team failed to establish clear communication channels, address disruptive communication patterns, and leverage each member’s strengths through open dialogue.

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ A meeting of five business professionals, with a woman at the head of the table](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/74/2025/04/Ch4c-1.jpg)

This scenario underscores the critical role of communication in understanding group dynamics and fostering effective collaboration. In this chapter, we’ll explore how to build strong teams by establishing clear communication protocols, how to improve active listening and participation, how to address communication challenges, and how to evaluate group processes through feedback loops.

4.1 Identify Various Roles Within a Group

Every group has members who fulfill specific roles that contribute to the team’s success. These roles can be categorized into three main types: task roles, maintenance roles, and leadership roles (Benne & Sheats, 1948; Bettencourt & Sheldon, 2001; Odell et al., 2004; Stoeckle & O’Shea, 2024). Participants in groups can fill multiple roles for their group, and not every group has to have every role to be high-functioning. Understanding these roles helps successfully address all aspects of group work: task completion, relationship building, and effective leadership. These roles develop over time and can be traced along the stages of group development. By starting with a discussion about the stages of group development, we will better understand how the roles within a group come to exist.

Stages of Group Development

Just as individuals grow and change, groups also progress through predictable stages of development. Understanding these phases, originally proposed by Bruce Tuckman (1965) and later expanded with Mary Ann Jensen (2010), provides a helpful framework for recognizing common group behaviors and challenges. These five stages are:

-

Forming: In this initial stage, group members are typically polite and tentative, getting to know each other and the group’s purpose. There’s often an eagerness to be accepted, and members may rely heavily on a designated leader for direction. The focus is on establishing ground rules, defining roles, and understanding the task at hand.

-

Storming: As members become more comfortable, conflict and competition often emerge. Different ideas, personalities, and working styles can clash, leading to disagreements about tasks, roles, or leadership. This stage is crucial for the group to work through tensions, establish trust, and learn how to manage differences productively.

-

Norming: If a group successfully navigates the storming phase, they move into norming. Here, members begin to resolve their differences, develop a sense of cohesion, and establish shared norms, procedures, and expectations for how they will work together. Trust builds, roles become clearer, and the group develops a collective identity.

-

Performing: This is the stage where the group operates at its most efficient and effective. With established norms and strong relationships, members are focused on achieving their common goals. Conflict, when it arises, is managed constructively, and the group can adapt to challenges, make decisions collaboratively, and leverage individual strengths for optimal results.

-

Adjourning: For temporary groups, such as project teams, the adjourning stage marks the conclusion of the group’s work and its eventual disbandment. This phase involves wrapping up tasks, celebrating achievements, and allowing members to disengage from the group. It can involve feelings of accomplishment, but also a sense of loss for the camaraderie built.

Understanding these stages allows group members and leaders to anticipate challenges, adjust communication styles, and provide appropriate support to help the group progress towards high performance.

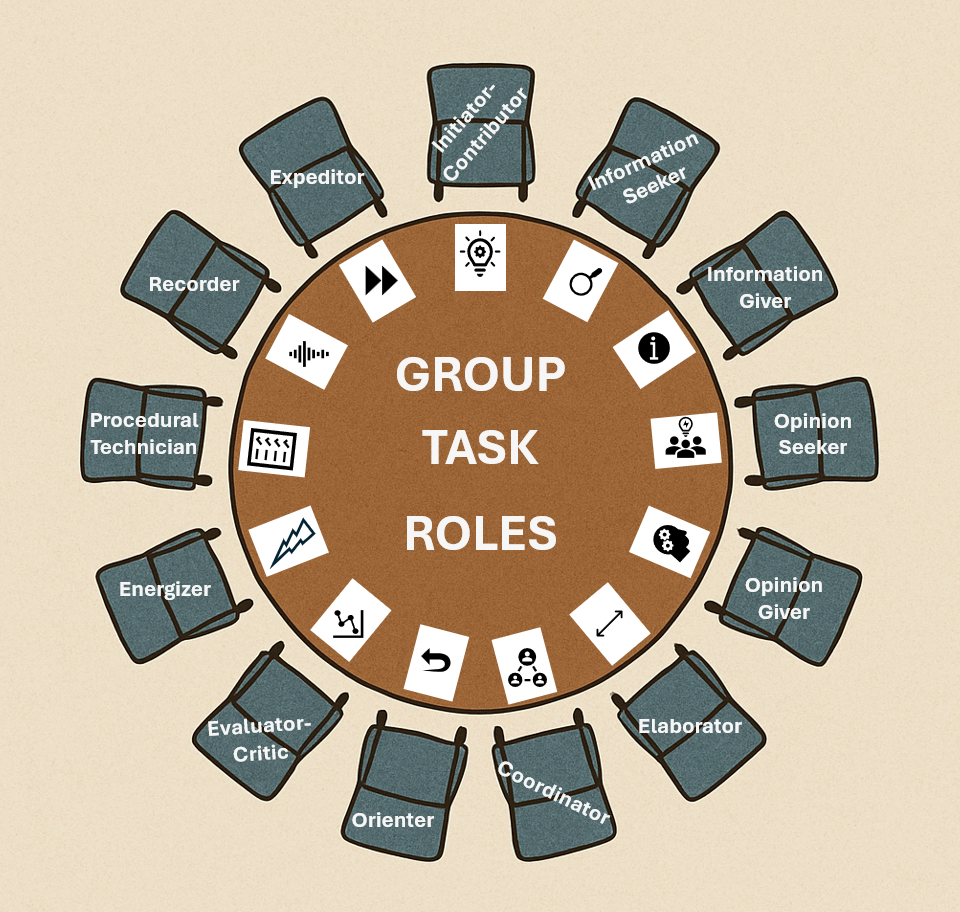

Task Roles

Within any group striving for a common goal, distributing task-related roles is key to achieving efficiency and effectiveness. These roles, focused on completing the group’s objective, encompass a range of communication functions, from initiating ideas and seeking information to evaluate progress and coordinating efforts. The following list highlights the diverse task-oriented contributions members can make, describing how these roles collectively drive a group towards successful outcomes.

| Team Member | Role |

| Initiator-Contributor | Proposes new ideas, suggests solutions, and offers fresh perspectives |

| Information Seeker | Asks for clarification, seeks relevant facts, and ensures the group has necessary data |

| Information Giver | Provides relevant information, shares expertise, and offers personal experiences |

| Opinion Seeker | Seeks to understand the values and opinions of group members |

| Opinion Giver | Expresses personal beliefs and opinions and offers suggestions based on values |

| Elaborator | Expands on ideas, provides examples, and clarifies concepts |

| Coordinator | Connects ideas, organizes information, and integrates contributions |

| Orienter | Keeps the group focused, clarifies goals, and redirects discussions |

| Evaluator-Critic | Analyzes ideas, assesses feasibility, and evaluates the group’s progress |

| Energizer | Spurs the group to action and motivates the group to higher productivity levels |

| Procedural Technician | Handles logistical tasks, such as distributing materials and arranging the meeting space |

| Recorder | Takes notes, documents decisions, and maintains records |

| Expediter | Keeps the group on track, manages the agenda, and monitors progress |

| Encourager | Praises, supports, and acknowledges the contributions of others. Creates a positive and welcoming atmosphere. |

| Harmonizer | Mediates conflicts, reduces tension, and helps resolve disagreements. Seeks to find common ground and promote cooperation. |

| Compromiser | Offers compromises and admits errors to maintain group harmony. Willing to yield their own position for the sake of the group. |

| Gatekeeper | Encourages participation from all members and ensures everyone has a chance to speak. Regulates communication flow and prevents domination by a few individuals. |

| Standard Setter | Sets and maintains standards for group behavior and performance. Helps the group establish norms and expectations. |

| Follower | Accepts and supports the ideas and decisions of the group. Goes along with the group’s direction. |

| Tension Releaser | Uses humor or other methods to relieve stress and create a relaxed environment. |

Maintenance Roles

Beyond the tangible tasks that drive a group’s progress, the maintenance of a healthy and cohesive environment is equally critical. In this context, maintenance refers to the ongoing efforts and behaviors that preserve and strengthen the social and emotional well-being of a group. Group maintenance roles focus on fostering positive relationships, managing conflict, and ensuring the emotional well-being of all members (Stoeckle & O’Shea, 2024). This works by actively addressing interpersonal dynamics, supporting individual contributions, and creating a safe space for open communication. These roles, which range from encouraging participation and mediating disagreements to setting standards and relieving tension, are essential for creating a supportive atmosphere where collaboration can thrive. Within groups, standards function as guidelines for behavior, with some being explicitly stated rules and others operating as implied norms. Rules are formally articulated expectations, such as “meetings start precisely at 9 a.m.,” while norms are the unwritten, shared understandings about acceptable behaviors, like always allowing everyone a chance to speak or celebrating individual contributions.

Leadership Roles and Group Dynamics

Leadership roles involve guiding a group toward its goals, ensuring that objectives are met while maintaining harmony among members. These roles can be formal, such as a designated leader chosen through appointment or election, or informal, such as an emergent leader who assumes influence through their actions, contributions, and ability to connect with others. Effective leaders recognize the need to balance both task responsibilities and maintenance responsibilities, understanding that success depends not only on accomplishing goals but also on maintaining group cohesion and morale (Pizzo et al., 2025; Wrench et al., 2020). In practice, this means fostering a collaborative environment where productivity and satisfaction are equally valued. For example, in a student group project, a leader may not only assign research tasks to ensure progress but also organize regular check-ins to support members, resolve conflicts, and address anxieties. This dual attention to productivity and group well-being helps ensure both the completion of the project and the preservation of team unity. Effective group functioning, therefore, often hinges on a thorough understanding of leadership as well as the broader dynamics of power within the group. It is important to note that while often used interchangeably, the terms “leader” and “leadership” refer to distinct but interrelated ideas.

Leader vs. Leadership

A leader is an individual recognized by others as occupying a role of guidance or authority within a group. This person may hold a formal title such as chairperson or manager, or they may rise informally to the position by earning respect and trust through their behavior and contributions. A leader is therefore a role, a title, or a person who becomes the focal point of direction within a group

Leadership, on the other hand, refers not to the individual but to the process of influence itself. Leadership is the set of actions, behaviors, and strategies used to inspire, guide, and motivate others toward the achievement of shared goals. Unlike the concept of a leader, leadership is not confined to a specific title or role. Anyone in a group can practice leadership by demonstrating initiative, fostering collaboration, or offering guidance, regardless of formal recognition. This distinction helps us see that leadership is not something reserved for those at the top of a hierarchy, but a dynamic process that can emerge from any member of the group.

Leadership Styles

The manner in which a leader influences and guides others is often described as their leadership style. While many models exist, three foundational approaches provide a useful framework for understanding how leadership operates. Autocratic leadership, also called authoritarian leadership, emphasizes control and decision-making by the leader alone, with little input from group members. This approach allows for quick decisions and may be effective in emergencies or with inexperienced teams, but it often reduces morale and creativity when overused. Democratic leadership, sometimes referred to as participative leadership, encourages group members to contribute ideas and take part in decision-making processes. The leader facilitates discussion, seeks input, and strives for consensus, fostering motivation and creativity while still maintaining the ability to make final decisions when necessary. This approach works well with motivated and experienced teams but may be slower in contexts that require immediate action. Laissez-faire leadership, a French term meaning “allow to do,” represents a hands-off approach where the leader provides minimal direction and allows team members to manage themselves. This can be empowering for skilled and self-motivated individuals who thrive on independence, but it may result in confusion or inefficiency if group members require more structure or guidance. Each leadership style has strengths and weaknesses, and effective leaders often adapt their style depending on the group’s needs and the situation at hand.

Understanding Power

Power within a group refers to the ability to influence others or shape their behavior, and it differs from authority, which is the legitimate right to exercise such influence. Power is not limited to formal titles or hierarchical positions but can emerge from a variety of sources. Legitimate power arises from formal roles, such as managers or team leads, who are granted the right to direct others by virtue of their position. Coercive power stems from the capacity to punish or impose negative consequences, compelling compliance through the threat of harm or loss, though it often breeds resentment when relied upon too heavily. Reward power is the counterpart to coercive power and comes from the ability to provide benefits, recognition, or opportunities valued by others. Expert power develops from specialized knowledge or skill that others depend on, making the expert’s opinion particularly influential. Referent power, sometimes called social power, originates from respect, admiration, or personal appeal, enabling individuals to inspire loyalty or voluntary compliance through charisma or integrity. By recognizing these different forms of power, group members and leaders alike can better understand how influence functions and how it can be exercised responsibly to build cohesion and achieve shared goals.

Leadership Roles

One important role within groups is the task leader, whose primary function is to help the group accomplish its objectives. Task leaders are essential for productivity, ensuring that activities remain focused, resources are used effectively, and progress is steady toward the completion of goals. They focus on what must be done and how best to do it, keeping the group organized and aligned with its purpose. Within task leadership, two primary types can be identified: the substantive leader and the procedural leader.

The substantive leader is the intellectual driver of the group, often providing expertise, generating ideas, and contributing deep knowledge to ensure the quality of outcomes. This leader plays a key role in problem-solving, innovation, and the content-related aspects of a group’s work. For example, in a complex engineering project, the substantive leader might be the senior engineer who proposes a new design for integrating renewable energy sources. Their insights, grounded in technical expertise, push the group forward by shaping the conceptual framework of the project. Substantive leaders often command respect through their knowledge, and their contributions ensure that the group’s solutions are not only functional but also sophisticated and forward-thinking.

The procedural leader ensures that the group functions efficiently by managing the process through which tasks are accomplished. This individual focuses less on generating ideas and more on organizing the group’s workflow, creating agendas, assigning responsibilities, and monitoring progress. For instance, in the aftermath of a power outage, a procedural leader might serve as the foreperson who develops a step-by-step plan for restoring service. They assign specific tasks to team members, enforce safety protocols, and ensure communication flows smoothly between the crew and central dispatch. Through this structure, the procedural leader keeps the group moving forward and prevents confusion or disorganization from undermining the group’s objectives.

4.2 Manage Needs Within Groups

A successful group thrives on a foundation of fulfilled needs, encompassing both the practical requirements of task completion and the essential elements of social and emotional well-being (Sheldon & Bettencourt, 2002; Chun & Choi, 2014). From establishing clear goals and fostering effective communication to cultivating trust and promoting inclusion, a group’s ability to address these diverse needs directly impacts its overall effectiveness and member satisfaction. The following list highlights the multifaceted needs of a group and describes the critical factors that contribute to a productive and harmonious collaborative environment.

Task-Related Needs

For a group to be productive and effective, it must first address its task-related needs. First and foremost, a group requires clear goals and objectives, ensuring that every member shares a unified understanding of what they are trying to achieve. To work toward these goals, effective communication is essential, as it allows for an open, honest, and respectful exchange of ideas and information. This communication is supported by organized processes, which provide structured methods for problem-solving, decision-making, and task completion. In addition, a group must have resource availability, ensuring that members have access to the necessary tools and support to complete their work. Once tasks are underway, there must be defined roles and responsibilities so each member has a clear understanding of their contributions and expectations. As the group progresses, progress monitoring and evaluation become necessary to regularly assess the group’s effectiveness and how it is moving toward its goals. When obstacles arise, the group must have the ability to engage in problem-solving and decision-making to effectively work through challenges and come to conclusions. Finally, all these elements are held together by a culture of accountability, where each member is responsible for their portion of the work, ensuring the group can successfully reach its objectives.

Maintenance/Social-Emotional Needs

While focusing on tasks is crucial, a group’s success also depends on fulfilling its maintenance and social-emotional needs. This begins with building trust and respect, creating a safe and supportive environment where every member feels valued. From this foundation, a sense of cohesion and belonging can develop, fostering a feeling of unity and connection among members. These positive feelings are sustained by a positive communication climate, which is built on constructive feedback, active listening, and supportive interactions. Since disagreements are inevitable, the group must also have strong conflict management strategies to resolve issues and maintain harmony. Additionally, inclusion and participation are essential to ensure all members have opportunities to contribute and feel heard, which reinforces a positive and unified group. To further reinforce this, recognition and appreciation for each member’s contributions are necessary. These efforts are often guided by a set of shared norms and values, or a mutual understanding of acceptable behaviors and guiding principles. Ultimately, a successful group provides emotional support, ensuring that members know they can rely on one another.

Individual Needs

For a group to truly thrive, it’s not enough to just meet the group’s needs; each member must also have their individual needs met. A key individual need is a sense of purpose, where members feel that their contributions are meaningful and valued. The group should also provide opportunities for growth and development, allowing members to learn new skills and expand their knowledge. In addition, members require a certain level of autonomy and independence, which gives them some control over their work and contributions. Finally, every individual needs to feel that they are receiving fair treatment and are being treated equitably. By addressing these individual needs, the group can increase member satisfaction, engagement, and overall productivity.

Strategies For Effective Participation

To ensure a group meets all of its needs—from task-related to individual—members must employ effective participation strategies. This begins with active listening, where each person pays full attention to others’ ideas and shows their engagement through nonverbal cues like nodding or maintaining eye contact. Building on this, members should provide constructive feedback that is specific, actionable, and respectful, helping the group improve without causing offense. Equally important is respectful communication, which involves using inclusive language and avoiding interruptions to ensure everyone has an opportunity to be heard. Finally, all these strategies come together in collaboration, allowing members to work with others to build on ideas, find solutions, and achieve a successful outcome together.

4.3 Identify and Manage Negative Group Behaviors

Groups, while powerful tools for collaboration, can be undermined by negative behaviors that disrupt progress and erode cohesion (Kuehmichel, 2022). From task-related hindrances like blocking and dominating, to social-emotional determinants such as aggression and gossip, these actions can create a toxic environment and hinder a group’s ability to achieve its goals. For instance, imagine a coworker, David, who consistently shuts down new ideas during team meetings by saying, “That’s not how we do things here,” without offering alternatives (blocking), then talks over others to push his own agenda (dominating), and later spreads rumors about why a colleague’s suggestion failed (gossip). The following list outlines a spectrum of negative behaviors commonly observed within groups, highlighting the importance of recognizing and addressing these patterns to foster a more productive and harmonious collaborative experience.

Task-Related Negativity and Strategies for Managing It

Negative behaviors directly impede a group’s ability to achieve its objectives by disrupting the work process and hindering progress on the task at hand. Various negative behaviors are explained below, along with strategies for managing them.

Blocking

Blocking is a behavior that involves consistently rejecting ideas or opposing group decisions without offering constructive alternatives, which creates an obstacle to the group’s forward momentum. For example, during a team brainstorming session for a new product, one member repeatedly said, “That’s a terrible idea, it won’t work,” without ever explaining why or suggesting an alternative. This constant opposition prevented the group from exploring potentially viable solutions and led to frustration.

To address this, leaders should encourage the blocker to provide specific, constructive alternatives and explain their opposition. By facilitating a discussion to explore the validity of their concerns, you can move the conversation forward. For instance, during a classroom debate on a controversial policy, a teacher might prompt a student who says, “That’s just wrong, it won’t work,” with, “Can you elaborate on your concern and perhaps suggest an alternative approach that addresses it?” This shifts the focus from simple negation to constructive contribution.

Dominating

Dominating refers to an individual’s tendency to monopolize discussions and control the flow of conversation, preventing other members from contributing their thoughts or opinions. For example, in a group project meeting, one student spoke almost continuously, dictating decisions and shutting down others’ attempts to speak by talking over them. As a result, several quieter members became disengaged, feeling their contributions were unwelcome and unnecessary.

To manage this behavior, groups can implement structured speaking turns or time limits. Using gatekeeping techniques can also ensure everyone has a chance to contribute. If a member is dominating, gently interrupting and redirecting the conversation is often effective. In a family discussion about vacation plans, for instance, a parent who is monopolizing the conversation might be gently interrupted by a partner with, “That’s a lot of great ideas, my love. Let’s make sure everyone gets a chance to share their top choice, starting with the kids.”

Withdrawing

Withdrawing occurs when a group member disengages from the task, remaining silent, refusing to participate in discussions, or physically distancing themselves from the group’s activities. For instance, when asked to contribute to a group’s research outline, one member sat silently, avoiding eye contact and offering no input despite repeated invitations. Their disengagement forced other group members to take on additional responsibilities to ensure the task was completed.

To address this behavior, a leader or peer should directly address the individual in a private, non-confrontational setting. They can ask about their concerns and offer support or assign specific, manageable tasks to re-engage them. As an example, a respiratory therapy student who observed a peer consistently sitting silently during clinical debriefs might privately ask, “I’ve noticed you’re quiet during debriefs. Is everything okay, or is there anything I can do to help you feel more comfortable sharing?”

Distracting

Distracting is an individual behavior that involves introducing irrelevant topics, telling off-topic jokes, or engaging in other behaviors that divert the group’s attention away from its primary objectives. For instance, every time the group starts discussing a complex problem, a particular member would crack a joke or bring up a completely unrelated social media trend. These constant diversions made it difficult for the group to maintain focus and significantly prolonged their work session.

To manage this behavior, members should firmly but respectfully redirect the conversation back to the task at hand. Setting clear agendas and time frames for discussions can also help keep the group on track. If the behavior persists, it may be necessary to address the individual privately. As a simple example, in a study group, if someone started telling a long story about their weekend during a complex problem-solving session, a classmate might interject with, “That’s hilarious, but let’s quickly get back to this calculus problem before time runs out.”

Information Hoarding

Information hoarding is the deliberate act of withholding crucial data, insights, or knowledge that is relevant to the group’s task, thus hindering collective problem-solving and decision-making. For example, a team member who is responsible for collecting crucial data for a report consistently fails to share it with the rest of the group, even when asked directly. This intentional withholding forced others to make assumptions or duplicate efforts, severely delaying the report’s completion.

To counter this, a group should establish a culture of transparency and information sharing from the beginning and clearly define expectations for how and when information will be disseminated. This behavior can be addressed by emphasizing the importance of collaboration. For example, a doctor who keeps critical patient updates to themselves, forcing coworkers to search for details, might be gently reminded during a shift change that, “All relevant patient information must be communicated verbally and documented immediately in the shared system for continuity of care.”

Work Avoidance/Social Loafing

Work avoidance, also known as social loafing, describes the tendency of an individual to exert less effort when working in a group than they would individually, relying on other members to complete the shared responsibilities and carry the workload. For example, during a shared presentation, one student consistently missed deadlines for their assigned slides and rarely responded to group messages, expecting others to cover their parts. The rest of the team ended up working overtime to compensate for their lack of contribution and ensure the presentation was ready.

To manage this behavior, the group should clearly define individual responsibilities and deadlines at the outset. They can also implement peer evaluations and accountability systems, and provide opportunities for individual recognition to motivate all members. For instance, in a classroom group project where one member wasn’t doing their part, the group leader might propose creating a shared document where each member checked off their completed tasks daily, making individual contributions visible and accountability clear to everyone.

Maintenance/Social-Emotional Negativity and Strategies for Managing It

These behaviors undermine the group’s internal harmony and positive working relationships, often stemming from personal issues or interpersonal friction rather than directly from the task itself. Types of these behaviors are explained below, along with strategies for managing them.

Aggression

Aggression is a group behavior that involves directly attacking other members personally, using hostile language, or displaying overtly uncooperative behavior. It creates a tense and unsafe atmosphere that makes others hesitant to contribute. For example, during a disagreement about a project’s scope, Sarah yelled at a teammate, “You’re an idiot for even suggesting that! You clearly don’t understand how this works.” This personal attack immediately shut down the discussion and created hostility within the group.

To manage aggression, it’s crucial to immediately address the behavior in a calm and assertive manner and to establish clear rules for respectful communication. If necessary, a group can take a break or even reschedule a meeting to let emotions cool down. For instance, if a family member started yelling during a heated discussion about holiday plans, another family member might calmly interject, “We need to lower our voices. We can’t solve this problem if we’re yelling at each other. Let’s take a moment and try again.”

Recognition Seeking

Recognition seeking is a group behavior that involves constantly trying to draw attention to oneself, boasting about individual accomplishments, or demanding praise and validation from the group. This behavior shifts the focus from collective success to personal ego. For example, even after the team successfully launched a project, Truman repeatedly interrupted discussions to remind everyone how his “brilliant idea” was the only reason they succeeded. He continuously sought compliments, diverting attention from the group’s collaborative effort.

To manage this, group members should acknowledge contributions fairly and equitably, then redirect the focus to the group’s overall goals. Providing opportunities for all members to shine is also key. When a student in a group project constantly highlighted their own achievements, the group leader might acknowledge their specific contribution once, then shift focus by saying, “Your research on X was excellent, and it really helped our team put together a strong argument for Y.”

Self-Confessing

Self-confessing occurs when a group member uses the group as a platform for personal therapy, sharing inappropriate or irrelevant personal problems. It forces the group to listen to private issues that are unrelated to the task at hand. In the middle of planning a presentation, for example, Maria started recounting a lengthy, detailed story about a fight she had with her roommate that morning. The other group members felt awkward and unsure how to respond, losing valuable time and focus on their task.

To address this, it is best to gently redirect the conversation back to the group’s task. In some cases, it may be appropriate to suggest that the individual seek support outside of the group. During a classroom discussion about marine life, for instance, if a student began to share personal emotional struggles, the teacher might gently interject, “I’m sorry to hear you’re experiencing that. How about we continue talking after class? In the meantime, let’s keep our focus on marine life for the purpose of this discussion.”

Playing the Victim

Playing the victim is a group behavior that involves constantly complaining about personal difficulties, blaming others for problems, and acting as if everything negative is happening to them. This behavior seeks sympathy and deflects responsibility. For instance, whenever a deadline approached, John would lament, “I can’t believe I have to do all this work. No one else is pulling their weight!” He consistently complained about being overwhelmed, even when tasks were equally distributed, making others feel resentful.

To counter this, acknowledge the individual’s feelings, but avoid reinforcing their victimhood. Instead, encourage them to focus on solutions and take responsibility for their own actions. If a friend constantly complained about being “stuck” with bad luck in their life, a supportive friend might respond, “I hear you’re going through a lot, and that sounds really tough. What’s one small step you think you could take to start turning things around?”

Cynicism

Cynicism describes a pervasive negative outlook where an individual consistently expresses doubt, dismisses new ideas, and makes pessimistic comments about any group initiative. It can quickly dampen enthusiasm and creativity. For example, as the group brainstormed fresh ideas for an event, Demetrius sighed loudly and interjected, “That’s pointless; it’s never going to work anyway. We tried something similar last year and it failed miserably.” His constant negativity discouraged further innovative suggestions.

To manage this, it is important to challenge cynical statements with factual information and positive examples. By doing so, you can encourage the individual to offer constructive suggestions. When an engineer’s colleague dismissively stated, “This new protocol is just more paperwork; it won’t help anyone,” a proactive peer might reply, “I understand your skepticism, but the data from the pilot program showed a 15% reduction in errors. Do you see any specific areas where we could improve its implementation?”

Gossip/Backbiting

Gossip and backbiting are group behaviors that involve speaking negatively or spreading rumors about other group members behind their backs, rather than addressing issues directly. It erodes trust and fosters a divisive atmosphere. For instance, after a team meeting, Willa pulled a few colleagues aside to whisper criticisms about how another member handled their presentation. This backbiting created suspicion and undermined the cohesion of the group.

The most effective way to combat this is to establish a zero-tolerance policy for gossip and encourage direct, respectful communication. You should also address the behavior immediately when it happens. If a student overheard classmates gossiping about a peer in their project group, they might calmly interject, “Hey, if there’s an issue with how someone is contributing, it’s probably best to talk to them directly about it, not here.”

Conflict Causing

Conflict causing is the intentional act of provoking arguments, making inflammatory comments, or trying to create division and tension among group members. The goal is often to disrupt harmony or draw attention. For example, when group members had a minor disagreement, Julian intentionally exaggerated their differences and made sarcastic remarks designed to escalate the tension. His actions turned a small misunderstanding into a heated argument, disrupting the group’s work.

To manage this behavior, group leaders should mediate conflicts using active listening and conflict resolution techniques. It is crucial to facilitate open and honest communication and to establish clear ground rules for respectful debate. When a classroom group member intentionally made inflammatory comments to provoke arguments during a discussion, the instructor might step in and say, “Let’s pause. We are here to debate ideas, not attack each other. Please refer to our ground rules for respectful communication.”

Individual Negativity and Strategies for Managing It

These behaviors stem from a single member’s personal tendencies and primarily affect their own contribution and the overall group dynamic, rather than directly targeting the task or interpersonal relations within the group.

Resistance to Change

Resistance to change is a behavior that involves an individual’s refusal to adapt to new ideas, procedures, or technologies, preferring to cling to outdated methods. This can significantly hinder a group’s ability to innovate and improve efficiency. For example, when a team decided to switch to new project management software, one member repeatedly insisted on using their old spreadsheet system. They refused to learn the new platform, causing delays and forcing others to manually transfer their updates.

Addressing this behavior requires a leader to directly engage with the individual’s concerns. In the above situation, the manager can say, “I understand your concerns regarding the new software and its implementation. This change can prove to be challenging. However, this software was selected by management because after a pilot led by your peers, it showed an increase in efficiency and reduced errors. Your participation in the training sessions is crucial for a smooth implementation across the organization. If you have concerns or ideas, please schedule a one-on-one meeting with me. Your feedback is important, and I want you to feel supported during this transition.” This response combines validation with clear expectations, helping the individual feel heard while reinforcing the importance of the change.

Lack of Accountability

Lack of accountability describes an individual’s failure to take responsibility for their actions, mistakes, or unfulfilled commitments, often deflecting blame onto others. This behavior erodes trust and frustrates teammates who are left to cover for them. For instance, after missing a crucial deadline, a team member immediately blamed the IT department for slow internet and a colleague for not reminding them, refusing to acknowledge their own procrastination or poor time management.

To manage this behavior, groups must clearly define expectations and consequences from the start and actively foster a culture of responsibility. This can be supported by regular performance evaluations and feedback sessions. For example, if a student repeatedly failed to submit their portion of a group assignment, the group leader might meet with them, explicitly outlining the impact on their grade and the group, and set up clear check-ins for future tasks to reinforce individual responsibility.

Negative Attitude

An individual with a negative attitude is characterized by consistently expressing pessimism, complaining frequently, and generally spreading a dispiriting outlook throughout the group. Such negativity can drain morale and stifle motivation. For example, whenever a new idea was proposed, one member would sigh loudly and remark, “That’s just going to create more work for us, and it probably won’t even matter.” Their constant complaining made it difficult for others to maintain a positive and productive mindset.

To address this, it’s best to focus on positive achievements and progress, and encourage the individual to identify solutions rather than dwelling on problems. This can be done by providing positive reinforcement. To address a family member constantly complaining about every aspect of a planned family gathering, another family member might try to pivot the conversation by saying, “I hear your concerns, but let’s also remember the delicious food and fun games we’re planning. What’s one thing you’re looking forward to, or one idea you have to make it even better?”

Passive-Aggression

Passive-aggression involves expressing negative feelings indirectly through subtle hostility, procrastination, sarcasm, or unstated resentment rather than direct confrontation. It creates an underlying tension and makes conflict resolution difficult. For example, when asked to take on an extra task, a team member agreed with a tight, fake smile, but then told the team at the last minute they couldn’t complete it because of how “busy” they were, subtly conveying their annoyance without directly expressing it.

To manage this behavior, it is crucial to address it directly and calmly. This encourages open and honest communication and helps to get to the underlying issue. For instance, if a roommate consistently “forgot” to take out the trash after agreeing to it, the other roommate might calmly state, “I’ve noticed the trash hasn’t been taken out. If you’re feeling overwhelmed or there’s an issue with the chore schedule, please tell me directly so we can adjust it.”

General Strategies for Managing Negative Group Behavior

Establish Clear Group Norms

When starting any collaborative work, a crucial first step is to establish clear group norms. This involves creating and enforcing ground rules for respectful communication and behavior before any issues arise. By proactively setting these expectations, a group can prevent problems and create a clear framework for accountability. For example, a classroom group working on a presentation might agree on a rule like “Everyone gets 5 minutes to share initial ideas without interruption,” or “If you have a conflict with a team member, talk to them directly first.” This strategy ensures that all members are on the same page and understand the expected conduct from the very beginning.

Facilitate Open Communication

Another strategy for managing group behaviors is to facilitate open communication. This means actively encouraging members to express their concerns and provide feedback. The goal is to create a safe and non-judgmental space where individuals feel comfortable voicing issues, whether they are about the task at hand or interpersonal dynamics. For example, a couple facing a recurring argument might agree to use "I" statements and set aside specific times to discuss frustrations. By doing this, they can ensure each person feels heard without immediate defensiveness, which is a key component of this strategy.

Provide Training

A highly effective way to proactively manage negative group behaviors is to provide training that equips members with the foundational skills to navigate difficult situations. This involves offering training on essential skills such as communication, conflict resolution, and teamwork. By equipping individuals with these specific skills, you empower them to navigate difficult situations more effectively and positively, which benefits all interactions within the group. For instance, a building supervisor might arrange a workshop on active listening and de-escalation techniques to help staff members manage challenging customer interactions more calmly. This proactive approach helps to build a more capable and harmonious group.

Mediation

When direct communication proves difficult, another effective strategy is to use mediation. This involves bringing in a neutral third party to mediate disagreements when needed. A neutral party can help facilitate communication, identify underlying issues, and guide individuals toward a mutually agreeable solution without taking sides or assigning blame. For example, when three roommates were unable to agree on chore responsibilities, a mutual friend stepped in to help them outline their concerns and negotiate a fair cleaning schedule. This approach helps to restore harmony and resolve conflicts that members cannot solve on their own.

Regular Feedback

Giving feedback on both positive and negative behaviors is a valuable practice for improving any group. Consistent, specific, and timely feedback helps individuals understand the impact of their actions and provides clear opportunities for growth and adjustment. For example, after a shift, a charge nurse might praise a new grad for their efficient charting while gently advising another nurse to improve their hand-off report clarity. This approach encourages desirable behaviors and proactively addresses problematic ones, fostering a culture of continuous improvement within the group.

Address Problems Early

The final strategy for managing negative group behaviors is to address problems early. This means not letting minor issues become major ones. By tackling issues as soon as they arise, a group can prevent them from escalating, becoming deeply ingrained, and causing more significant disruptions later. For example, if a student group leader noticed a member consistently missing small deadlines, they’d have a quick, private conversation after the first instance rather than waiting for a major project milestone to be missed. This proactive approach helps to maintain the group’s efficiency and a positive collaborative environment.

4.4 Evaluate the Process of Group Interactions

To keep a group effective and support ongoing improvement, it’s important to assess how members work together (Nikoleizig et al., 2021; Stoeckel, 2024). This requires both personal reflection and group discussion. From introspective self-reflection and candid peer feedback to structured process observation and insightful group debriefs, these techniques provide valuable insights into the group’s dynamics and performance. The following list overviews each of these evaluation methods, highlighting their importance in cultivating a collaborative and productive group environment.

Self-Reflection

Self-reflection is the process of thoughtfully examining one’s own thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and experiences to gain a deeper understanding of oneself. Consider your contributions, how you talk, and how you affect everyone else. It involves stepping back from immediate actions or reactions to analyze why you did what you did, how you felt, and what impact your actions had. This introspective practice allows for personal growth, learning from past experiences, and conscious adjustment of future behaviors. It means you deliberately look at your own behavior in the group. Self-reflection questions to consider include: Did I actively listen to others? Did I contribute meaningfully to the task? Did I handle conflicts constructively? Did I uphold group norms and values? How could I improve my participation in future meetings? Self-reflection is a very important tool because it allows each group member to take ownership of their own actions.

Feedback

Exchanging constructive feedback with other group members is a vital process that involves both giving and receiving insights to foster individual and collective improvement. This practice often comes in two distinct but complementary ways: peer feedback and group feedback. Peer feedback typically involves individuals providing specific observations and suggestions to one another regarding their contributions, communication style, or performance on tasks. This is a direct, one-on-one exchange aimed at helping an individual grow. In contrast, group feedback, or a group debrief, is a more comprehensive, collective reflection that happens after a task or project is completed. While peer feedback focuses on individual actions, a group debrief examines the synergy and effectiveness of the entire unit to analyze what worked well and what didn’t.

When giving feedback, you should focus on specific behaviors and their impact rather than making personal attacks. Use “I” statements (e.g., “I felt that…”) and offer suggestions for improvement. When receiving feedback, listen actively, avoid defensiveness, and ask clarifying questions. Viewing feedback as an opportunity for growth is key to the process. Peer feedback can happen informally outside of meetings or formally through structured feedback sessions. These discussions promote transparency, build trust, and help individuals understand how their actions are perceived by others, allowing for multiple perspectives to be shared.

Process Observation

Process observation involves systematically observing and analyzing how the group functions as a whole. It’s about paying attention to communication patterns, decision-making processes, conflict-resolution strategies, and overall group dynamics. Observers can use checklists, rating scales, or detailed note-taking to record their observations. The areas to observe include participation levels (who speaks and how often), communication styles (both verbal and nonverbal), decision-making methods (such as consensus or voting), conflict management, and the distribution of roles. This technique provides valuable insights into the group’s strengths and weaknesses, enabling targeted interventions for improvement.

Group Debriefs

Group debriefs are structured discussions held after meetings or activities to reflect on the group’s performance. The purpose is to identify what worked well, what could be improved, and how to apply lessons learned to future interactions. For example, after a theatrical performance, the director and cast might hold a debriefing session to discuss specific scenes where blocking was effective, areas where line delivery could be clearer, or how the pacing of the entire show felt to the audience, all with the goal of improving future performances. These discussions should be facilitated to ensure everyone has an opportunity to contribute. Key questions to address might include: What were our successes? What challenges did we encounter? How effectively did we communicate? How can we improve our processes? What action items should we take? Group debriefs foster a culture of continuous improvement and promote collective learning and adaptation.

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ Several students working together on a project, using laptops and personal devices](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/74/2025/04/Ch4g.jpg)

Real-World Application

Imagine a student group working on a complex presentation about nanotechnology. After their first rehearsal, each member engaged in self-reflection, noting areas where they felt their delivery faltered and where they could improve their content. Following this, they participated in peer feedback, offering constructive criticism on each other’s presentation style and clarity of arguments, using specific examples from the rehearsal. During the next rehearsal, one member took on the role of process observer, noting the group’s communication patterns, such as who dominated the discussion and how effectively they addressed disagreements. After the second rehearsal, they held a group debrief, discussing the observations made, identifying key areas for improvement, and creating action items to address them before the final presentation. This combination of self-reflection, peer feedback, process observation, and group debriefs allowed the student group to identify their strengths and address weaknesses, leading to a significantly improved final presentation.

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ Office meeting around a large table with the facilitator counting the number of people with hands raised](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/74/2025/04/aitubo-7.jpg)

4.5 Decision-Making Strategies

Effective decision-making is a cornerstone of successful group collaboration, yet the path to a decision can vary significantly (Azer, 2004; Gobaert & Cao, 2020). Various group dynamics, mood, and the type of communication used can affect group decision making (Armson et al., 2023; Hinsz & Robinson, 2025). From the inclusive process of consensus to the efficient method of majority vote and the decisive approach of authority rule, each strategy carries its own set of advantages and disadvantages. The following section offers an overview of these decision-making techniques, explaining their processes, benefits, and potential drawbacks to provide a comprehensive understanding of how groups navigate the crucial task of reaching conclusions.

Consensus

Consensus is a decision-making process that typically involves open dialogue, active listening, and a willingness to compromise. This approach is characterized by honesty, transparency, and mutual respect, where all participants feel safe to freely express their thoughts and perspectives without fear of judgment. The goal is to build a deeper understanding and collaboratively explore issues rather than to simply debate. When successful, this process has several advantages: it fosters high buy-in from group members since they feel involved in the decision, it enhances collaboration and strengthens relationships, and it leads to comprehensive solutions by considering diverse perspectives. However, consensus has its drawbacks. It can be time-consuming and may lead to groupthink, where the desire for agreement outweighs critical evaluation. It can also cause compromise fatigue, where members agree to solutions they don’t truly believe in, which can result in less effective outcomes.

Majority Vote

Majority vote is a straightforward decision-making method where a proposed solution is implemented if more than half of the group members vote in favor of it. This process, commonly practiced in school boards and Congress, can be conducted through a show of hands, a secret ballot, or electronic voting. Its primary advantage is efficiency, as it is quick and easy to implement, especially in large groups, and it provides a clear outcome with minimal ambiguity. On the other hand, majority vote can lead to minority dissatisfaction, causing feelings of resentment among those whose opinions were not represented. It can create a “winners” and “losers” dynamic that fractures group cohesion and may result in a lack of consideration for all angles of a problem due to the speed of the decision.

Authority Rule

Authority rule is a decision-making method in which a designated leader or an expert makes the final decision, often after consulting with the group for input. This process is commonly used by CEOs and managers. The leader may solicit feedback, conduct research, or consider various options before making a final decision. This method is praised for its speed and efficiency, as it allows for rapid decision-making, particularly in time-sensitive situations. It also establishes clear accountability, as there is a single point of responsibility, and can lead to a more consistent output. However, this method has notable disadvantages. It can lead to reduced group ownership, which may decrease motivation and engagement among group members. It can also stifle creativity and diverse perspectives and may result in over-reliance on one person to provide all the answers.

4.6 Chapter Summary

Teamwork and collaboration are essential for achieving shared goals, but they require careful attention to group dynamics, roles, and processes. This chapter explored how to identify and fulfill group roles, participate effectively in group interactions, address negative behaviors, evaluate group processes, and analyze decision-making strategies. By understanding these concepts, you can contribute meaningfully to any group, foster a collaborative environment, and achieve better outcomes in both personal and professional settings.

Key Takeaways

- Groups rely on task, maintenance, and leadership roles to function effectively.

- Understanding and balancing roles ensures that all aspects of group work are addressed.

- Active participation, constructive feedback, and respectful communication are essential for successful group interactions.

- Identifying and addressing negative behaviors helps maintain a positive group environment.

- Evaluating group processes and decision-making strategies improves collaboration and outcomes.

Wrap-Up Questions

- The chapter emphasizes that clear goals and objectives are fundamental for a group’s task-related needs. Recall a group experience (academic, professional, or personal) where the goals were unclear. What specific communication breakdowns or inefficiencies resulted from this ambiguity, and how did it impact the group’s ability to achieve its objectives or satisfy its members?

- The chapter introduces general strategies for managing negative group behavior, which include establishing clear group norms and addressing problems early. Choose one of the task-related negativity behaviors (blocking, dominating, work avoidance/social loafing, etc.). Describe how implementing these two strategies proactively could reduce the likelihood or impact of that specific negative behavior in a new group.

- The text details various maintenance/social-emotional negativity behaviors, including aggression, gossip/backbiting, and conflict causing. Imagine you are a group leader. If you observe a member exhibiting passive-aggression, what specific verbal and nonverbal cues would you look for to confirm this behavior, and how would you approach addressing it given the indirect nature of passive-aggression?

- Self-reflection is highlighted as a crucial tool for individual growth within a group. Consider a time you felt a group interaction could have gone better. Using the self-reflection questions provided in the text (e.g., Did I actively listen?, Did I handle conflicts constructively?), analyze your own contribution to that interaction. What specific personal insight did you gain, and how might it inform your behavior in a future group setting?

- The concept of groupthink is mentioned as a potential disadvantage of consensus. Describe a hypothetical or real-world scenario where the desire for harmony in a group led to groupthink during a decision-making process. What might have been overlooked as a result, and how could a group deliberately incorporate strategies to prevent groupthink while aiming for high buy-in?

4.7 Learning Activities

Learning Activity 4.1

Learning Activity 4.2

Learning Activity 4.3

4.8 References

Armson, H., Moncrieff, K., Lofft, M., & Roder, S. (2023). “Change talk” among physicians in small group learning communities: An ethnographic study. Medical Education, 57(11), 1036–1053. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.15120

Azer, S. A. (2004). Becoming a student in a PBL course: Twelve tips for successful group discussion. Medical Teacher, 26(1), 12-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142159032000156533

Benne, K. D., & Sheats, P. (1948). Functional roles of group members. Journal of Social Issues, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4560.1948.tb01783.x

Bettencourt, B. A., & Sheldon, K. (2001). Social roles as mechanisms for psychological need satisfaction within social groups. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81(6), 1131. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/11761313/

Chun, J. S., & Choi, J. N. (2014). Members’ needs, intragroup conflict, and group performance. Journal of Applied Psychology, 99(3), 437. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036363

Gobaert, A., & Cao, M. (2020). Strategically influencing an uncertain future. Scientific Reports, 10(1), 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-69006-x

Hinsz, V. B., & Robinson, M. D. (2025). A conceptualization of mood influences on group judgment and decision making: The key function of dominant cognitive processing strategies. Small Group Research, 56(1), 71–113. https://doi.org/10.1177/10464964241274124

Kuehmichel, S. (2022). Examining small-group roles through team-building challenges. Communication Teacher, 36(4), 275–280. https://doi.org/10.1080/17404622.2021.2024866

Nikoleizig, L., Schmukle, S. C., Griebenow, M., & Krause, S. (2021). Investigating contributors to performance evaluations in small groups: Task competence, speaking time, physical expressiveness, and likability. PLoS ONE, 16(6), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0252980

Odell, J., Nodine, M., & Levy, R. (2004). A metamodel for agents, roles, and groups. In International Workshop on Agent-Oriented Software Engineering (pp. 78–92). Springer Berlin Heidelberg. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-540-30578-1_6

Pizzo, M., Terrance, S., & Abu-Ras, W. (2025). Online project-based learning in small groups: Innovative approaches to leadership development for social work students. Social Work With Groups, 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/01609513.2025.2454023

Sheldon, K. M., & Bettencourt, B. A. (2002). Psychological need‐satisfaction and subjective well‐being within social groups. British Journal of Social Psychology, 41(1), 25–38. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466602165036

Stoeckel, M. R. (2024). Using group roles to promote collaboration. The Science Teacher, 91(6), 73–77. https://doi.org/10.1080/00368555.2024.2404955

Stoeckel, M. R., & O’Shea, K. (2024). Strategies for supporting equitable group work. Physics Teacher, 63(5), 326–329. https://doi.org/10.1119/5.0167278

Tuckman, B. W. (1965). Developmental sequence in small groups. Psychological bulletin, 63(6), 384.

Tuckman, B. W., & Jensen, M. A. C. (2010). Stages of small-group development Revisited1. Group Facilitation, (10), 43-48.

Wrench, J. S., Punyanunt-Carter, N. M., & Thweatt, K. S. (2020). Interpersonal communication: A mindful approach to relationships. Milne Open Textbooks. https://milneopentextbooks.org/interpersonal-communication-a-mindful-approach-to-relationships/

Images:

Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/

“Group_task_roles” by Nic Ashman, Chippewa Valley Technical College is licensed under CC BY-NC 4.0

Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/

Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/

The communication behaviors and actions within a group that are directly focused on facilitating the accomplishment of the group's specific goals and objectives. Unlike maintenance roles, which address group cohesion, task roles are centered on the output and productivity of the group.

The communication behaviors and actions within a group that are focused on building, maintaining, and strengthening internal relationships, group cohesion, and a positive social climate. Unlike task roles, which are directly related to achieving the group's specific objectives, maintenance roles address the emotional and interpersonal needs of the group members.

The specific functions, responsibilities, and behaviors that individuals assume or are assigned when guiding, influencing, and directing a group or organization towards the achievement of shared goals. These roles are multifaceted and can include, but are not limited to, setting vision and strategy, motivating team members, making decisions, fostering collaboration, managing conflict, coaching, mentoring, representing the group, and serving as a role model.

The stage when a group gets to know each other and the group’s purpose, with a focus on establishing ground rules, defining roles, and understanding the task at hand.

When a group works through tensions, establishes trust, and learns how to manage differences productively.

When a group begins to resolve their differences, develop a sense of cohesion, and establish shared norms, procedures, and expectations for how they will work together. Trust builds, roles become clearer, and the group develops a collective identity.

When a group operates at its most efficient and effective with established norms and strong relationships, members are focused on achieving their common goals.

Communication that marks the conclusion of the group’s work and its eventual disbandment.

The group member who proposes new ideas, suggests solutions, and offers fresh perspectives.

The group member who asks for clarification, seeks relevant facts, and ensures the group has necessary data.

The group member who provides relevant information, shares expertise, and offers personal experiences.

The group member who seeks to understand the values and opinions of each group member.

The group member who expresses personal beliefs and opinions and offers suggestions based on values.

The group member who expands on suggestions or ideas offered by others, providing examples, explanations, and details to help the group understand the implications of a proposal. This role helps clarify and develop concepts, ensuring that all members are on the same page and that ideas are thoroughly explored before a decision is made.

The group member who connects ideas, organizes information, and integrates contributions.

The group member who keeps the group focused, clarifies goals, and redirects discussions.

The group member who analyzes ideas, assesses feasibility, and evaluates the group’s progress.

The group member who spurs the group to action and motivates the group to higher productivity levels.

The group member who handles logistical tasks, such as distributing materials and arranging the meeting space.

The group member who takes notes, documents decisions, and maintains records.

The group member who keeps the group on track, manages the agenda, and monitors progress.

The group member who praises, supports, and acknowledges the contributions of others. Creates a positive and welcoming atmosphere.

The group member who mediates conflicts, reduces tension, and helps resolve disagreements. Seeks to find common ground and promote cooperation.

The group member who offers compromises and admits errors to maintain group harmony. Willing to yield their own position for the sake of the group.

The group member who encourages participation from all members and ensures everyone has a chance to speak and regulates communication flow and prevents domination by a few individuals.

The group member who sets and maintains standards for group behavior and performance. Helps the group establish norms and expectations.

The group member who accepts and supports the ideas and decisions of the group. Goes along with the group’s direction.

The group member who uses humor or other methods to relieve stress and create a relaxed environment.

An individual who occupies a formal or informal role within a group and is often recognized by others as having the authority or responsibility to guide the group.

Process of influencing a group of people towards the achievement of a common goal.

Also known as authoritarian leadership, this style involves the leader making decisions independently with little to no input from group members.

Often referred to as participative leadership, this style involves leaders who encourage group participation in decision making.

This leadership style is characterized by a “hands-off” approach.

Refers to the ability to influence others or control their behavior.

This type of power stems from an individual’s formal position or role within a hierarchy or organization.

This power is based on the ability to punish or impose negative consequences if others do not comply.

The opposite of coercive power, reward power is derived from the ability to offer positive incentives or benefits to influence behavior.

This power comes from an individual’s specialized knowledge, skills, or expertise that others value and rely upon.

A role whose primary function is to help the group accomplish its objectives.

Often the “idea” person or the intellectual driver of the group.

The person who gives the most guidance on how the group operates and progresses through its task.

Requirements that cultivate a healthy and productive group environment, focusing on interpersonal dynamics.

This group behavior involves consistently rejecting ideas or opposing group decisions without offering constructive alternatives, thereby creating obstacles to the group’s forward momentum.

This group behavior refers to an individual’s tendency to monopolize discussions and control the flow of conversation, preventing other members from contributing their thoughts or opinions.

This group behavior occurs when a group member disengages from the task, remaining silent, refusing to participate in discussions, or physically distancing themselves from the group’s activities.

This individual behavior involves introducing irrelevant topics, telling off-topic jokes, or engaging in other behaviors that divert the group’s attention away from its primary objectives.

This group behavior is the deliberate act of withholding crucial data, insights, or knowledge that is relevant to the group’s task, thus hindering collective problem-solving and decision-making.

The tendency of an individual to exert less effort when working in a group than they would individually, relying on other members to complete the shared responsibilities and carry the workload.

This group behavior involves directly attacking other group members personally, using hostile language, or displaying overtly uncooperative behavior.

Having little to no regard for the other person’s concerns, prioritizing personal victory or avoidance.

This group behavior involves constantly trying to draw attention to oneself, boasting about individual accomplishments, or demanding praise and validation from the group.

This group behavior occurs when a group member uses the group as a platform for personal therapy, sharing inappropriate or irrelevant personal problems.

This group behavior involves constantly complaining about personal difficulties, blaming others for problems, and acting as if everything negative is happening to them.

The feeling of pity or sorrow for someone else's misfortune, suffering, or distress. Unlike empathy, which involves understanding and sharing another's feelings as if they were your own, sympathy is more about feeling compassion or concern for someone from a detached perspective.

This group behavior describes a pervasive negative outlook where an individual consistently expresses doubt, dismisses new ideas, and makes pessimistic comments about any group initiative.

These group behaviors involve speaking negatively or spreading rumors about other group members behind their backs, rather than addressing issues directly.

This group behavior is the intentional act of provoking arguments, making inflammatory comments, or trying to create division and tension among group members.

This behavior involves an individual’s refusal to adapt to new ideas, procedures, or technologies, preferring to cling to outdated methods.

This individual behavior describes an individual’s failure to take responsibility for their actions, mistakes, or unfulfilled commitments, often deflecting blame onto others.

This individual behavior is characterized by consistently expressing pessimism, complaining frequently, and generally spreading a dispiriting outlook throughout the group.

This group behavior involves expressing negative feelings indirectly through subtle hostility, procrastination, sarcasm, or unstated resentment rather than direct confrontation.

The shared, often unstated rules or guidelines that establish expectations for how members should behave and interact within a group. These norms define acceptable conduct, communication patterns, and overall group culture, contributing to its stability and effectiveness.

Statements that shift the focus from assigning blame to taking ownership of your own experience.

When a neutral third party remediates disagreements.

The process of thoughtfully examining one’s own thoughts, feelings, behaviors, and experiences to gain a deeper understanding of oneself.

Exchanging constructive feedback with other group members.

Systematically observing and analyzing how the group functions as a whole.

Structured discussions held after meetings or activities to reflect on the group’s performance.

A discussion and deliberation process where all group members work towards finding a solution with which everyone can agree.

A situation in which the desire for agreement outweighs critical evaluation.

A situation where members agree to solutions they don’t truly believe in because of the volume of decisions being made, which can result in less effective outcomes.

A method where the group votes on a proposed solution, and it implements the solution if more than half of the members vote in favor of it.

A designated leader or an expert in the field making the final decision, often after consulting with the group or gathering input.