Chapter 2: Nonverbal Communication

2.0 Introduction

Learning Objectives:

- Identify the types of nonverbal communication

- Apply effective nonverbal messages in diverse communication contexts

- Analyze how nonverbal cues influence verbal and nonverbal messages

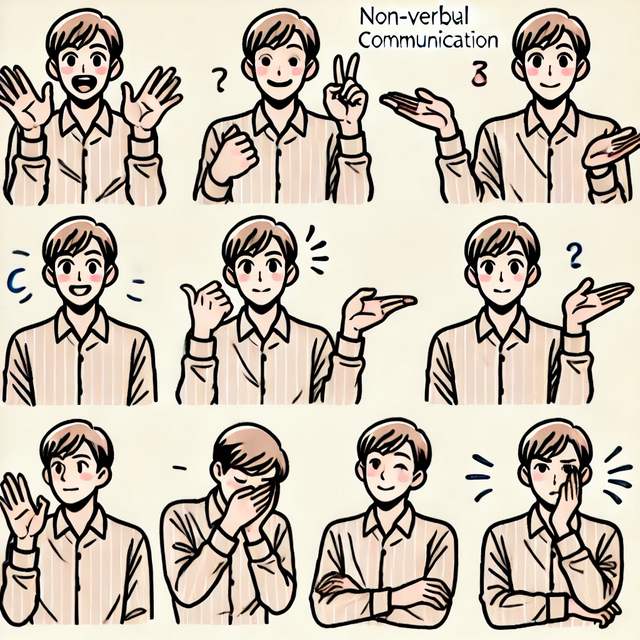

Nonverbal communication is the unspoken language that accompanies our words, influencing how messages are received and interpreted. Researchers contend that up to 70% of meaning conferred in communication is nonverbal (Hull, 2016). It includes facial expressions, body language, vocalics, and even the use of space and time. Body language refers to the conscious and unconscious movements and postures by which attitudes and feelings are communicated. It encompasses a vast array of physical signals, such as gestures (e.g., waving, pointing), posture (e.g., slumping, standing tall), and eye contact (e.g., direct gaze, averted eyes). These non-linguistic cues often operate in conjunction with verbal messages, either reinforcing, contradicting, substituting for, or regulating what is being said. Nonverbal communication’s meaning can be intended or unintended. Whether in personal relationships, professional settings, or digital interactions, mastering nonverbal skills can enhance understanding, build trust, and foster deeper connections.

A Short Story: The Power of a Smile

In a small village in Japan, a young traveler named Emma found herself lost and unable to speak the local language. Frustrated and anxious, she approached an elderly woman selling fruits at a market stall. Emma gestured toward a map, her face etched with worry. The woman, without saying a word, smiled warmly, handed her a ripe persimmon, and pointed in the direction Emma needed to go. That simple smile and kind gesture conveyed more than words ever could—comfort, reassurance, and hospitality. Emma later reflected on how that moment of nonverbal communication not only helped her find her way but also left a lasting impression of human connection.

![Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/ A smiling, elderly Asian woman is offering the viewer an orange](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/74/2025/04/Ch2b-701x1024.jpg)

This story illustrates the profound impact of nonverbal communication, which encompasses far more than just gestures. It includes vocal nonverbal communication, or paralanguage, referring to how we say words through elements like tone, pitch, volume, and rate of speech, adding layers of meaning beyond the literal words. It also involves nonvocal nonverbal communication, such as facial expressions, body posture, gestures, and eye contact, all of which display emotions and ideas. Crucially, nonverbal cues can be both voluntary (like a deliberate wave) and involuntary (like a nervous tremor or a micro-expression of fear), often providing insights into true feelings that verbal communication might mask. However, it’s vital to recognize the inaccuracy inherent in interpreting nonverbal cues in isolation, as their meaning is highly dependent on context and culture. Despite this potential for misinterpretation, nonverbal communication profoundly impacts the flow and presentation of our messages, often reinforcing or even contradicting our spoken words, thereby shaping how others perceive our credibility, sincerity, and emotional state.

At its core, nonverbal communication is deeply rooted in our evolutionary history. Before humans developed spoken language, we relied on nonverbal signals to communicate things like threat, safety, and approval. Our brains are hardwired to quickly process these visual and auditory cues because our survival often depended on rapidly understanding the intentions and emotions of others. This is why nonverbal signals often feel more powerful and authentic than words alone; they can reveal a person’s true feelings and help us form immediate connections.

2.1 Identifying the Types of Nonverbal Communication

The subtle cues and unspoken signals we exchange often carry as much, if not more, meaning than our verbal expressions. This section delves into the multifaceted world of nonverbal communication, exploring nine key categories: kinesics, the language of body movements; haptics, the power of touch; vocalics, the subtleties of tone and pitch; proxemics, the use of personal space; and chronemics, the communication of time, personal presentation, physical characteristics, artifacts, and environments (Burgoon et al., 2021). Each of these areas plays a vital role in shaping our understanding and interpretation of messages, revealing the intricate and often unconscious ways we connect with one another.

Kinesics (Body Language)

Kinesics refers to the study of body movements, including gestures, facial expressions, posture, head movements, and eye contact. These nonverbal cues provide rich information about a person’s thoughts, feelings, and intentions. For example, while a thumbs-up signals approval and a furrowed brow indicates confusion, head movements like a nod can convey agreement or understanding, and a shake can signal disagreement. Eye contact is particularly powerful; direct eye contact can communicate sincerity, interest, or challenge, while avoiding eye contact might suggest shyness, dishonesty, or deference, depending on cultural context. Beyond these, hand gestures are a fascinating subset of kinesics, categorized by their functions explained below. Together, these various forms of kinesics provide a constant stream of nonverbal data that influences how messages are sent and received.

Adaptors

Adaptors are unintentional, often unconscious gestures that satisfy a personal need, such as scratching an itch, twirling hair, or fiddling with a pen when nervous. They are not usually intended to communicate, but they can still reveal how someone feels. Examples include tapping a foot during a tense moment, fiddling with a pen while waiting, or rubbing one’s neck during a stressful conversation. These actions may involve touching oneself, interacting with objects, or even making small, absentminded gestures toward others. Because they tend to appear during moments of nervousness, boredom, or discomfort, adaptors often serve as subtle signals of a person’s internal state.

Illustrators

Illustrators are gestures that accompany and literally “illustrate” what is being said verbally, making the message clearer or more vivid. They help paint a visual picture of what is being said, making ideas easier to understand. For example, a speaker might spread their arms to show size, point in a direction while giving instructions, or mimic the action of drinking to illustrate a story. While illustrators are often planned in the moment, they can also feel natural and spontaneous, blending smoothly into speech. They vary across cultures, with some societies using them frequently and others relying on them less.

Emblems

Emblems are well-defined gestures that carry a specific, agreed-upon meaning within a culture, functioning almost like a word or short phrase. A simple wave can say “hello” or “goodbye,” a thumbs-up can signal approval, and the “V” sign can represent peace or victory. Unlike illustrators, emblems can stand entirely on their own without any spoken words. Their meanings are learned through cultural experience, and they can differ greatly from one region to another. A gesture that feels friendly and positive in one country might have a completely different, even offensive, meaning somewhere else, which makes cultural awareness especially important when using them.

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. (April 28 version) [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/ Four hand gestures and a child making four different facial expressions](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/74/2025/04/Kinesics-1024x507.png)

Haptics (Touch)

Haptics refers to communication through touch, a powerful nonverbal channel that can convey a wide range of emotions and messages. Touch can convey emotions ranging from affection (e.g., a hug) to aggression (e.g., a shove). Its appropriateness depends heavily on the relationship between individuals and the cultural context. A firm handshake at the beginning of a business meeting can nonverbally convey professionalism and confidence, whereas an unsolicited pat on the back from a stranger might be perceived as an invasion of personal space and cause discomfort. Different types of haptic communication are often categorized by the level of intimacy and context explained below. Understanding these different types of haptics is crucial for navigating social interactions effectively and interpreting the nuanced meanings conveyed through physical contact.

Professional Touch

Professional touch is practical, task-oriented, and usually impersonal. It takes place within a service or work-related context, where the purpose of the contact is functional rather than emotional. Examples include a nurse adjusting a patient’s position in bed, a massage therapist applying pressure to relieve muscle tension, or a coach tapping a player on the shoulder to guide their movement. In these cases, the interaction is framed by professional roles, and the meaning of the touch is tied to completing a job or providing assistance. Because the intent is not personal, boundaries are usually clear, but professionals are still expected to be mindful of comfort levels, cultural norms, and ethical guidelines.

Social Touch

Social touch occurs in polite or friendly interactions that follow social conventions. These touches are often brief, low in intimacy, and used to acknowledge or connect with others in everyday situations. A handshake when greeting someone, a congratulatory pat on the back, or a light touch on the forearm to get someone’s attention are common examples. While generally acceptable, the frequency and style of social touch can vary by culture—what feels warm and welcoming in one region might seem overly familiar in another. Successful use of social touch depends on reading the other person’s comfort level and adjusting accordingly.

Friendship Touch

Friendship touch expresses personal warmth, trust, and closeness between friends. It is more intimate than social touch, but it is usually not romantic. This category includes embraces that last longer than a quick greeting, linking arms while walking together, or giving a reassuring squeeze on the shoulder during a difficult conversation. Friendship touch helps strengthen bonds and can provide emotional comfort, but it is also shaped by individual personalities and cultural values. In some groups, friends hug frequently and without hesitation; in others, such gestures are reserved for special occasions or moments of strong emotion.

Love/Intimacy Touch

Love or intimacy touch conveys deep affection, emotional connection, and often physical attraction. It includes holding hands for extended periods, prolonged hugging, cuddling, or gentle caresses. These gestures occur mainly between romantic partners or close family members and communicate trust, vulnerability, and closeness. Because love or intimacy touch is highly personal, it is generally reserved for private or socially appropriate settings. In many cases, these touches are an important part of maintaining emotional connection and expressing care in relationships.

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. (April 28 version) [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/ A closeup of a care provider sitting next to and holding another person's hands in a supportive touch gesture](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/74/2025/04/6aeaddd0-cb17-4463-a260-7d534f30ffd8-1024x683.png)

View the following supplementary YouTube video to learn more: The Beauty of Touch | Patrick McIvor | TEDxLehighRiver

Vocalics

Vocalics, also known as paralanguage, refers to the nonverbal elements of the voice that accompany and often modify the meaning of spoken words. It follows the old adage that “it is not what you say, but how you say it.” According to Peter A. Andersen (1999), key aspects of vocalics include pitch, volume, rate, vocal quality, and verbal fillers explained below. Each of these vocalic elements works in conjunction with verbal messages to create a complete picture of meaning, influencing how a speaker is perceived and how their message is interpreted.

Pitch

Pitch refers to how high or low a voice sounds, and it can strongly influence the way a message is received. A higher pitch is often associated with excitement, enthusiasm, or nervousness, while a lower pitch tends to suggest seriousness, authority, or calmness. In everyday conversation, pitch naturally rises and falls, helping to convey emotion and keep the listener engaged. However, pitch changes can also alter meaning. For example, if a speaker ends a statement with a rising pitch, it can sound like a question even if they intended it as a firm declaration. Skilled speakers use pitch intentionally to emphasize key points, signal transitions, and create a dynamic, engaging delivery.

Volume

Volume refers to the loudness or softness of a person’s voice, and it plays a central role in shaping a listener’s perception. Speaking with a strong, clear volume can signal confidence, energy, or urgency, while speaking softly can create a sense of intimacy, secrecy, or gentleness. On the other hand, an overly loud voice may be interpreted as aggressive or overbearing, while a voice that is consistently too quiet can make it difficult for others to hear and may give the impression of shyness or disinterest. Effective communicators adjust their volume to match the environment, the formality of the situation, and the emotional tone they want to convey.

Rate

Rate describes the speed at which someone speaks, and it can affect both understanding and impression. A fast rate can convey enthusiasm, urgency, or excitement, drawing listeners in with its energy. However, if speech is too rapid, it can become difficult to follow, especially for listeners processing complex information or for those who are not fluent in the speaker’s language. A slow speaking rate can communicate thoughtfulness, seriousness, or emphasis, but if it is too slow, it can make the speaker seem uncertain, disengaged, or even condescending. Varying rate strategically allows a speaker to highlight key ideas while keeping the audience’s attention.

Vocal Quality

Vocal quality refers to the distinct characteristics of an individual’s voice, such as whether it is breathy, nasal, raspy, monotone, or clear and resonant. These qualities often develop naturally through physiology and speaking habits, but they have a powerful influence on how others perceive the speaker. A warm, resonant voice may be seen as friendly and trustworthy, while a creaky or overly nasal voice can distract listeners or unintentionally create a negative impression. Although vocal quality is partly innate, many aspects can be refined through vocal training, breathing exercises, and conscious practice.

Verbal Fillers

Verbal fillers are short sounds or words that people use to fill pauses in speech, such as “um,” “uh,” “like,” “you know,” or “so.” While occasional fillers are natural and can even give a speaker time to think, overusing them can make speech seem hesitant, unprepared, or lacking in confidence. In professional or high-stakes situations, excessive fillers may distract the listener from the message and undermine credibility. Awareness and practice can help reduce unnecessary fillers, allowing pauses to serve as intentional moments of emphasis or reflection instead.

![OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. (April 28 version) [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/ Illustration defining vocalics as a person making noise](https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/app/uploads/sites/74/2025/04/Screenshot-2025-06-05-230348.png)

Proxemics (Use of Space)

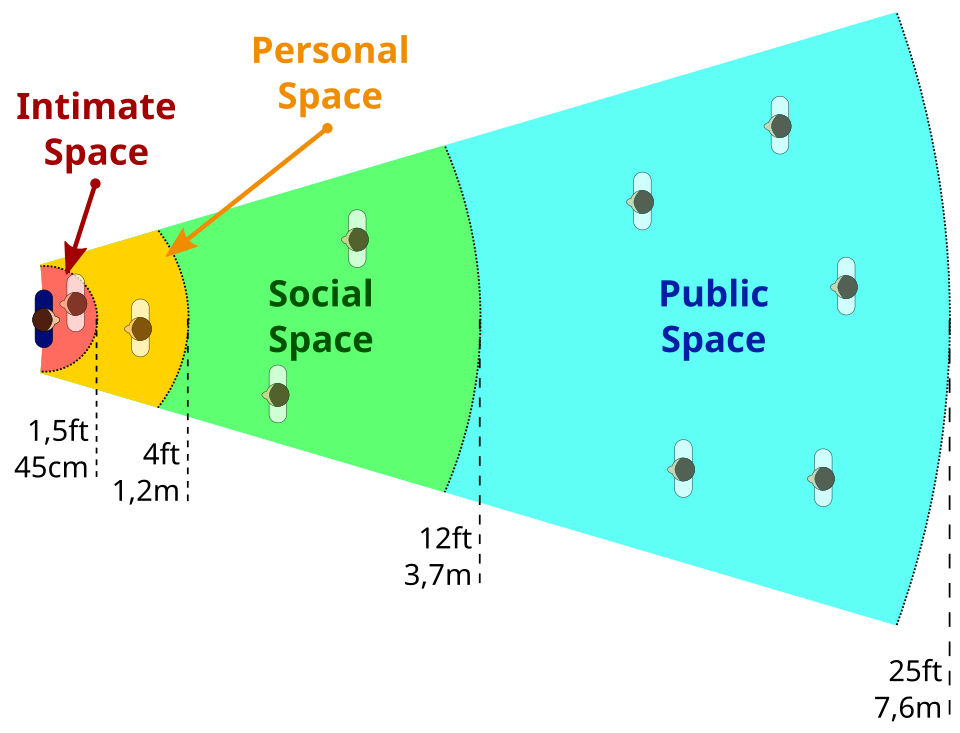

Proxemics examines how people use and perceive space, revealing deeply embedded cultural norms that influence appropriate distances in communication. In a casual conversation with a close friend, standing a foot or 2 apart is common in many Western cultures and nonverbally communicates comfort and intimacy. However, maintaining that same close distance with a new acquaintance might be perceived as aggressive or overly familiar, highlighting how cultural and relational contexts heavily influence the meaning of spatial cues. Edward T. Hall, a pioneering anthropologist, categorized interpersonal distances into four distinct zones (1966), emphasizing that these distances are not arbitrary but rather carry significant nonverbal meaning and vary culturally.

Intimate Space (0–1.5 Feet)

Intimate space, which extends from direct contact to about 1.5 feet, is reserved for the closest of relationships. Romantic partners, immediate family members, and very close friends often interact within this range. Communication here typically involves touch, whispered voices, and a strong awareness of sensory cues such as body warmth, scent, and subtle facial expressions. Because this zone is so personal, uninvited entry into it can feel intrusive or even threatening, triggering a defensive reaction.

Personal Space (1.5–4 Feet)

Personal space, ranging from 1.5 to 4 feet, is the comfortable distance most people maintain with friends and family during everyday conversations. This range allows for relaxed interaction without the intensity of intimate space, while still making it easy to reach out and touch or maintain steady eye contact. Personal space often functions as a protective “bubble” that helps balance closeness with comfort. Cultural expectations play a role here as well; in some cultures, standing closer is considered friendly, while in others, it may be perceived as too forward.

Social Space (4–12 Feet)

Social space, covering distances from 4 to 12 feet, is common for more formal exchanges. Interactions with acquaintances, co-workers in a professional setting, or participants in a small group discussion often take place at this range. Social space provides a comfortable buffer that supports clear communication while preserving a sense of professionalism. At this distance, gestures tend to be more visible, and vocal projection becomes more important for maintaining engagement.

Public Space (12+ Feet)

Public space, which begins at about 12 feet, is typical for addressing large groups, giving lectures, or speaking in public forums. In this zone, communication becomes more formal and less personal, often requiring speakers to raise their voices, make deliberate pauses, and use larger gestures to hold attention. Because facial expressions and subtle cues are harder to read at this distance, speakers often rely on broader movements and clear articulation to convey their message effectively.

Beyond these interpersonal distances, proxemics also considers territory, which refers to our tendency to claim and defend certain physical spaces as our own. This can range from our personal desk at work to a specific seat in a classroom or even a section of a park. Violations of these perceived territories can also trigger strong nonverbal and emotional responses. Understanding these spatial dynamics is crucial for effective and culturally sensitive communication.

Chronemics (Use of Time)

Chronemics refers to how time is used in communication, encompassing aspects like punctuality, the pace of interactions, and the amount of time one dedicates to another. The time you spend devoted to another person is often understood to be a measure of how much you value them; for instance, consistently being late for appointments or rushing conversations can nonverbally communicate a lack of respect or interest. Our perception and use of time, however, are heavily influenced by our culture, leading to significant differences in communication styles. Understanding these different cultural orientations to time is crucial for avoiding misinterpretations and fostering effective intercultural communication.

Monochronic and Polychronic Views of Time

In monochronic cultures, time is viewed as a linear and finite resource, emphasizing doing one task at a time and strict adherence to schedules. Punctuality is highly valued, and efficiency in completing tasks takes precedence. Sayings like “time is money” and “in the nick of time” are examples of how monochronic cultures value the concept of time, prioritizing schedules and promptness.

Polychronic cultures, on the other hand, see time as fluid and flexible, often engaging in multiple activities simultaneously and prioritizing relationships over strict adherence to schedules. Deadlines are typically seen as approximations, and interruptions are common and accepted as part of daily life. Sayings like “go with the flow” and “we’ll cross that bridge when we get to it” are examples of how polychronic cultures value the concept of time, emphasizing adaptability and interpersonal connections over strict temporal constraints.

Personal Presentation

Personal presentation consists of physical characteristics and artifacts. It encompasses how we style ourselves—our grooming, hygiene, and general appearance. These choices often communicate aspects of our personality, professionalism, or social status. For example, a meticulously groomed individual might be perceived as organized and detail-oriented, while a more relaxed presentation could signal an easygoing demeanor.

Physical characteristics refer to inherent or relatively stable features of our bodies, such as height, weight, body type, and natural hair color. While some of these are beyond our immediate control, they can still unconsciously influence initial perceptions and social interactions. For instance, societal biases sometimes associate certain body types with particular personality traits, even if these associations are unfounded.

Artifacts are the objects and accessories we choose to wear or display, including clothing, jewelry, piercings, tattoos, eyeglasses, and even the type of car we drive. These items act as extensions of our identity and can communicate a wealth of information about our cultural background, economic status, personal interests, and group affiliations. A person wearing a specific sports team’s jersey, for example, signals their allegiance to that team, while certain types of professional attire convey authority and credibility.

2.2 Applying Effective Nonverbal Messages in Diverse Contexts

Understanding nonverbal communication involves studying context through an interpretive lens. It involves the processes of encoding and decoding. Encoding is the process of developing a message and utilizing nonverbal communication that helps convey the message from sender to receiver. Decoding is the process of interpreting messages and creating meaning from both the verbal and nonverbal signals being communicated.

Contextuality of Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal cues—including those defined above—play a pivotal role in reinforcing, contradicting, or replacing verbal messages. In personal relationships, behaviors like a warm smile, a gentle touch, or sustained eye contact can convey affection, support, and attentiveness more effectively than words alone. For instance, a gentle hand squeeze can communicate comfort and empathy during challenging times, often surpassing the impact of verbal reassurances (Sauter, 2017). Using relationship-appropriate nonverbal messages provides communicators with a variety of strategies when conveying their feelings.

In professional settings, nonverbal communication is equally important. For example, during job interviews, maintaining eye contact, offering a firm handshake, adopting confident posture, and maintaining a well-kept personal appearance can create a positive impression and signal professionalism. Conversely, avoiding eye contact, slouching, or fidgeting may convey nervousness or lack of confidence, even if verbal responses are strong. These nonverbal behaviors can significantly influence hiring decisions and workplace dynamics (Burgoon et al., 2021).

Nonverbal behaviors are often categorized as “soft skills” and “hard skills.” Soft skills are a cluster of personal attributes and interpersonal abilities that enable individuals to interact effectively and harmoniously with others. Meanwhile, hard skills are technical knowledge or occupational proficiencies that are often quantifiable (e.g., coding, accounting, operating machinery). Therefore, soft skills are more about how you work and interact. They include qualities like communication, teamwork, problem solving, adaptability, emotional intelligence, and leadership. These skills are highly valued across all industries because they contribute significantly to productivity, collaboration, and a positive work environment.

An example of this is if a friend shares a deeply personal struggle or a tough experience. A soft skill like empathy is critical here. While verbal responses of support are important, the nonverbal communication can powerfully convey empathy. For instance, if you maintain gentle eye contact, offer a soft, concerned facial expression (like a slight furrowing of the brow or a downward turn of the lips), subtly lean in, and perhaps offer a comforting, brief touch on the arm, you are nonverbally communicating that you understand and share in their feelings. This nonverbal display of empathy, a vital soft skill, makes your friend feel truly understood and supported, deepening your connection.

In digital communication, nonverbal cues have evolved to fit virtual environments (Petruca-Rosa, 2023). Emojis, GIFs, and punctuation marks are often used to convey tone and emotion in text-based exchanges (Grishechko, 2023). For example, a smiley face emoji can soften a message’s tone, while excessive exclamation marks might indicate excitement or urgency. In addition, video conferencing platforms, like Zoom and Teams, have introduced nonverbal elements, such as facial expressions and gestures, due to limited eye contact and poor camera placement. Mastering these digital nonverbal cues is essential for maintaining clear and meaningful communication (Baylor, 2020). Digital communication may translate to different types of appropriate nonverbal behavior, but the importance in conveying your intended message remains.

The appropriateness and interpretation of nonverbal cues depend on the context, relationship, and cultural setting. For instance, a pat on the back might be encouraging in a personal setting but overly familiar in a formal environment. Similarly, a casual tone of voice with friends might seem disrespectful in a professional meeting (Segrin & Flora, 2019). Acknowledging power dynamics and expressions of respect are important when encoding nonverbal messages across contexts.

Cultural Awareness in Nonverbal Communication

Nonverbal behaviors are deeply influenced by cultural norms, and understanding these differences is crucial for effective communication in diverse settings. Both the processes of encoding and decoding vary among cultures. For example, direct eye contact is often seen as respectful and confident in Western cultures, but in some Asian cultures, it may be perceived as confrontational or disrespectful. Similarly, gestures like the “OK” hand sign can carry different meanings across cultures—approval in the United States but offense in parts of Europe and South America. Understanding cultural decoding associated with nonverbal communication is crucial for fostering cross-cultural relationships.

Personal space, or proxemics, also varies culturally. In many Western cultures, maintaining distance during conversations is seen as respectful, whereas in Middle Eastern or Latin American cultures, closer proximity often signifies warmth and friendliness. Misunderstanding these cultural norms can lead to discomfort or misinterpretation. For instance, standing too close to someone from a culture that values personal space might make them uneasy, while standing too far from someone who values closeness might seem cold or aloof.

The interpretation of nonverbal behaviors is heavily influenced by cultural norms, and varies widely across cultures. Understanding these cultural differences is essential for effective cross-cultural communication (Ting-Toomey & Chung, 2012). Adapting nonverbal behaviors to align with cultural norms is essential for building rapport and avoiding misunderstandings in cross-cultural interactions. When working with international colleagues or clients, learning about their cultural norms regarding eye contact, gestures, and personal space demonstrates respect and fosters positive relationships. Learning about these culturally specific nonverbal behaviors can be approached through several avenues. One effective way is through direct observation and immersion, such as living or traveling in a particular culture, which allows for firsthand experience of how nonverbal cues are used in daily interactions. Additionally, formal education and training, like taking intercultural communication courses or workshops, can provide structured knowledge and insights. Engaging with cultural informants—individuals from that culture who can explain and interpret their nonverbal norms—is also invaluable. Finally, research and reading reputable resources, including academic studies, ethnographies, and guides on specific cultures, can offer a foundational understanding before or during cross-cultural encounters.

2.3 Analyzing the Impact of Nonverbal Cues on Communication

Enhancing or Undermining Verbal Messages

Nonverbal cues often work in tandem with verbal messages to clarify or reinforce meaning (Stoica, 2024). People assess a speaker as sincere when their nonverbal cues—like tone, gestures, or facial expressions—match what they are saying emotionally. For example, saying “I’m excited to work on this project” while smiling and maintaining enthusiastic eye contact is considered congruent verbal and nonverbal behavior. Nonverbal cues also act as reinforcement when they complement messages to offer a visual match to the verbal message, such as pointing while giving directions.

However, when nonverbal cues contradict verbal messages, they can undermine the message. Examples such as saying “I’m not upset” while crossing your arms and avoiding eye contact can lead to confusion or mistrust. Undermining nonverbal communication can also be unintentional, like the change in vocalics and facial expression that comes along with lying. An example of this is the fluctuation in tone and uneasy smile that might accompany telling someone that they look nice in their new outfit, betraying your true feeling that they do not, and undermining the compliment.

Communicating Nonverbally in Conflict Resolution

Nonverbal cues play a critical role in managing and resolving conflicts. Calm and open body language like uncrossed arms and appropriate eye contact signals receptiveness and a willingness to listen, while aggressive behaviors like pointing fingers or raising your voice can escalate tensions (Segrin & Flora, 2019). In conflict resolution, nonverbal communication can aid in de-escalating tensions. Tone of voice, posture, eye contact, and touch are all nonverbal signals used to foster a collaborative environment for resolving disagreements.

For example, leaning slightly forward and nodding during a heated discussion can show engagement and empathy, helping to diffuse anger and encourage constructive dialogue (Burgoon et al., 2021). The process of de-escalation involves understanding the emotional state of the other person and being able to encode a message that will decrease their volatility. Recognizing someone’s emotional state is the process of reading their tone of voice, posture, and eye contact. Various factors can display anxiety (e.g., raised tone, shifting weight from side to side, rapid movements in eye contact), sadness (e.g., such as somber tone of voice, slouched posture, avoiding eye contact), and anger (e.g., louder tone, confrontational posture, unbreaking eye contact) as well as a variety of other emotional states.

Replacing Verbal Communication

In some situations, nonverbal cues can entirely replace verbal messages, making communication more efficient. Examples include a nod or thumbs-up to convey agreement or approval, holding up your index finger while on the phone to let the person next to you know that you will be with them shortly, or putting in your earbuds to convey to the world that you don’t want to talk – all without words. In digital communication, emojis and GIFs often replace traditional nonverbal behaviors to convey tone and emotion (Baylor, 2020). An example of this is using a meme as a replacement for a written reply.

Nonverbal communication is rarely isolated; it works in intricate ways with verbal messages, often serving to enhance, clarify, or even complicate what is being said. Rather than just replacing verbal communication, nonverbal cues fulfill six key functions in relation to our words:

-

Complementing: Nonverbal cues can add to, elaborate on, or reinforce a verbal message, providing a richer and more complete understanding. For instance, when you tell a friend “I’m so excited!” while simultaneously jumping up and down and smiling broadly, your nonverbal behavior complements your verbal statement, making your excitement undeniable.

-

Substituting: As previously noted, nonverbal cues can, in some situations, entirely replace verbal messages, making communication more efficient. Examples include a nod or thumbs-up to convey agreement, holding up your index finger to signal “one moment,” or putting in earbuds to indicate you don’t want to talk—all without uttering a word. In digital communication, emojis and GIFs often act as substitutes for traditional nonverbal behaviors to convey tone and emotion (Baylor, 2020), such as using a meme as a replacement for a written reply.

-

Contradicting: Perhaps one of the most powerful functions, nonverbal cues can send a message that is directly opposite to the verbal one, creating mixed signals. If someone says, “I’m not angry,” but their jaw is clenched, their eyes are narrowed, and their voice is tight, their nonverbal communication contradicts their verbal statement. In such cases, people often place more trust in the nonverbal cues as they are perceived as less intentional and more revealing of true feelings.

-

Accenting: Nonverbal communication can emphasize or highlight specific parts of a verbal message, drawing attention to particular words or ideas. For example, slamming your fist on a table while saying, “No, you don’t understand!” powerfully accents the word “No” and the intensity of your frustration. Similarly, a pause before delivering crucial information can accentuate its importance.

-

Repeating: Nonverbal cues can duplicate or reiterate the verbal message, strengthening its impact and aiding recall. When you verbally say “yes” while simultaneously nodding your head, the nonverbal action repeats the verbal message, reinforcing understanding for the receiver.

-

Regulating: Nonverbal cues play a vital role in managing the flow and pace of conversation, signaling when it’s appropriate for someone to speak or when a turn is ending. Eye contact, head nods, leaning forward, or even a shift in posture can act as regulators, indicating to others that you are listening, you wish to speak, or you are ready for the conversation to conclude.

The dynamic interplay between these six functions illustrates that nonverbal communication is not merely an auxiliary to words but an integral and often dominant component of how meaning is created and understood in human interaction.

Shaping Perception and Emotional Expression

Nonverbal communication significantly influences how others perceive us and how we express emotions. For instance, when meeting your partner’s parents for the first time, your initial nonverbal cues are crucial in setting the tone for the encounter. A relaxed posture, a genuine smile, and offering appropriate space conveys respect and openness, signaling that you’re genuinely interested in getting to know them. Conversely, fidgeting, avoiding eye contact, or displaying a tense posture might be interpreted as nervousness or discomfort, potentially creating an unintended barrier. Furthermore, the subtle choices you make, like how you position yourself in relation to them, or how gently you touch a proffered hand, will all contribute to the first impression. A slight lean forward, for example, can show you are engaged in the conversation, while a rigid posture might make you seem aloof. Each nonverbal cue is a silent message, shaping the parents’ perception of you even before meaningful verbal communication takes place.

Many perceptions that we hold of others are greatly influenced by their nonverbal communication (Hall et al., 2019). We think of people as aggressive or assertive based on vocalics, proxemics, and kinesics: if someone has a growling voice, looms over you, and gesticulates widely, we perceive those traits as aggressive. We also base our attribution of emotional intelligence on nonverbal communication. Effective nonverbal behaviors in the area of haptics, vocalics, and chronemics are associated with a person’s empathy, which is an important aspect of emotional intelligence. If someone has a soothing voice, a comforting touch, and spends a lot of their time attending to our wants and needs, then we perceive them as empathetic. Nonverbal communication has a variety of different effects on our perception of others. It’s important to recognize that interpretations of nonverbal cues are not universal. Cultural background, neurodiversity, gender norms, physical ability, socioeconomic context, and age all shape how nonverbal behaviors are expressed and perceived.

2.4 Chapter Summary

In this chapter, we explored the profound impact of nonverbal communication on our interactions. We discussed how nonverbal cues such as facial expressions, gestures, and tone of voice can reinforce, contradict, or replace verbal messages. We also examined the cultural nuances of nonverbal communication and how understanding these differences can enhance cross-cultural interactions. Finally, we analyzed the role of nonverbal communication in conflict resolution and emotional expression. By mastering nonverbal skills, you can improve your ability to connect with others, build trust, and foster deeper relationships in both personal and professional settings.

Key Takeaways

- Nonverbal communication is essential across personal, professional, and digital contexts. It includes facial expressions, body language, tone of voice, and the use of space and time.

- Nonverbal communication consists of kinesics, haptics, vocalics, proxemics, personal space, chronemics, personal presentation, physical characteristics, artifacts, and environments – each serving unique roles in conveying meaning and emotions.

- Cultural awareness enhances the effectiveness of nonverbal communication. Understanding cultural norms regarding gestures, eye contact, and personal space is crucial for avoiding misunderstandings.

- Nonverbal cues can enhance or undermine verbal messages, influence conflict resolution, and shape emotional expression. They can also replace verbal communication in certain situations and help us form perceptions of people.

Wrap-Up Questions

- The chapter highlights how nonverbal cues can carry as much, if not more, meaning than words. Consider a time you witnessed or experienced a significant disconnect between someone’s verbal message and their nonverbal communication (e.g., their kinesics like posture, or vocalics like tone). What specific nonverbal elements created this contradiction, and what impact did it have on the overall message received?

- The text discusses how nonverbal cues can reinforce, contradict, or replace verbal messages. Offer an example from your life when you used nonverbal cues in each of these ways. What are the similarities and differences in these examples?

- In the context of conflict resolution, the text highlights how nonverbal cues can de-escalate or escalate tensions. Imagine a heated disagreement in a professional team setting. What specific nonverbal behaviors (e.g., changes in posture, eye contact, or vocalics) could one person consciously employ to de-escalate the situation, even if the verbal exchange remains challenging?

2.5 Learning Activities

Learning Activity 2.1

Learning Activity 2.2

Learning Activity 2.3

2.6 References

Baylor, A. L. (2020). The impact of nonverbal communication in virtual environments. Journal of Digital Learning, 12(3), 45–52.

Burgoon, J. K., Guerrero, L. K., & Floyd, K. (2021). Nonverbal communication. Routledge.

Grishechko, E. G. (2023). Emojis as nonverbal cues in online communication: Perspectives on conflict resolution and misunderstanding prevention. SWS International Scientific Conference on Arts & Humanities, 333–340. https://doi.org/10.35603/sws.iscah.2023/s11.12.

Hall, E. T., & Hall, E. T. (1966). The hidden dimension (Vol. 609). Anchor.

Hall, J. A., Horgan, T. G., & Murphy, N. A. (2019). Nonverbal communication. Annual Review of Psychology, 70(2019), 271-294. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010418-103145

Hull, R. H. (2016). The art of nonverbal communication in practice. The Hearing Journal, 69(5), 22-24. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.HJ.0000483270.59643.cc

Petruca-Rosa, I. (2023). Parameters of nonverbal communication in social media. International Journal of Communication Research, 13(4), 301-303. https://www.ijcr.eu/articole/654_006%20Irina%20Petruca-Rosu.pdf

Sauter, D. A. (2017). The nonverbal communication of positive emotions: An emotion family approach. Emotion Review, 9(3), 222-234. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073916667236

Segrin, C., & Flora, J. (2019). The role of nonverbal communication in interpersonal relationships. In A. F. Hannawa & B. H. Spitzberg (Eds.), The handbook of communication science and biology (pp. 123–136). Routledge.

Stoica, D. S. (2024). The nonverbal: A more comprehensive view. Journal of the Seminar of Discursive Logic, Argumentation Theory & Rhetoric, 22(1), 88-117. https://www.fssp.uaic.ro/argumentum/Numarul%2022%20issue%201/04_Stoica_tehno.pdf

Ting-Toomey, S., & Chung, L. C. (2012). Understanding intercultural communication. Oxford University Press.

Images:

Images were created with Open AI: OpenAI. (2025). ChatGPT. (April 28 version) [Large language model]. https://chatgpt.com/ unless otherwise noted.

Aitubo. (2025). Flux (v1.0). [Artificial intelligence system]. https://aitubo.ai/

“Body_language_in_communication” by Paloma.chollet is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

“Personal_Spaces_in_Proxemics” by User:Jean-Louis Grall is licesned under CC BY-SA 3.0

“Comunicacion_intercultural” by Anamoralespon is licensed under CC BY-SA 4.0

“Understanding_in_Xian_0546” by S. Krupp, Germany is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0

Videos:

TEDx Talks. (2016, October 19). The Beauty of touch | Patrick McIvor | TEDxLeHighRiver [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=HCJoMzM_s3g

The unspoken language that accompanies our words, influencing how messages are received and interpreted.

Also known as paralanguage, vocalics refers to the nonverbal elements of the voice that accompany and often modify the meaning of spoken words.

The highness or lowness of a person’s voice.

The loudness or softness of a voice.

How quickly or slowly a person speaks.

The study of body movements, including gestures, facial expressions, posture, head movements, and eye contact.

Communication through touch.

How people use and perceive space, revealing deeply embedded cultural norms that influence appropriate distances in communication.

How time is used in communication.

Unintentional, often unconscious gestures that satisfy a personal need, which often indicate internal states like anxiety or discomfort.

Gestures that accompany and literally “illustrate” what is being said verbally, making the message clearer or more vivid.

Specific, culturally understood gestures that have a direct verbal translation and can often stand alone without words.

This type of touch is functional and impersonal, often occurring in a professional or service context.

This category includes touches that are part of polite social interaction and are generally impersonal.

This level of touch signals warmth, support, and closeness between friends. It’s more personal than social touch but typically not romantic.

This type of touch conveys deep affection, emotional connection, and often physical attraction between individuals in intimate relationships.

The unique characteristics of a person’s voice, such as breathiness, nasality, raspiness, or a clear, resonant tone.

Sounds or words that punctuate pauses in speech, such as “um,” “uh,” “like,” “you know,” or “so.”

Pursuing one’s own interests at the expense of others, potentially using power or force to win.

Intimate space is the closest of the four distance zones. It is the distance that extends from touch to about 18 inches away from a person.

Personal space is the second closest of the four distance zones, typically ranging from 1.5 to 4 feet away from a person.

Social space is the third of the four distance zones, extending from 4 to 12 feet away from a person.

Public space is the farthest of the four distance zones, beginning at about 12 feet from a person and extending outward.

The tendency to claim and defend certain physical spaces.

Cultures in which time is viewed as a linear and finite resource, emphasizing doing one task at a time and strict adherence to schedules.

Cultures in which time is fluid and flexible, often engaging in multiple activities simultaneously and prioritizing relationships over strict adherence to schedules.

Physical characteristics and artifacts.

Inherent or relatively stable features of our bodies, such as height, weight, body type, and natural hair color.

Objects and accessories we choose to wear or display, including clothing, jewelry, piercings, tattoos, eyeglasses, and even the type of car we drive.

Nonverbal cues that add to, elaborate on, or reinforce a verbal message.

Nonverbal cues that, in some situations, entirely replace verbal messages.

Nonverbal cues that send a message that is directly opposite to the verbal one.

Nonverbal communication that emphasizes or highlights specific parts of a verbal message, drawing attention to particular words or ideas.

Nonverbal cues that duplicate or reiterate the verbal message.

Nonverbal cues that signal when it’s appropriate for someone to speak or when a turn is ending.