6.4 Bones of the Axial Skeleton

Bones of the Axial Skeleton[1]

The axial skeleton includes the skull, the hyoid bone, the vertebral column, and the bones of the thoracic cage.

Skull

The skull is subdivided into the cranium (which surrounds and protects the brain) and the facial bones.

Cranium

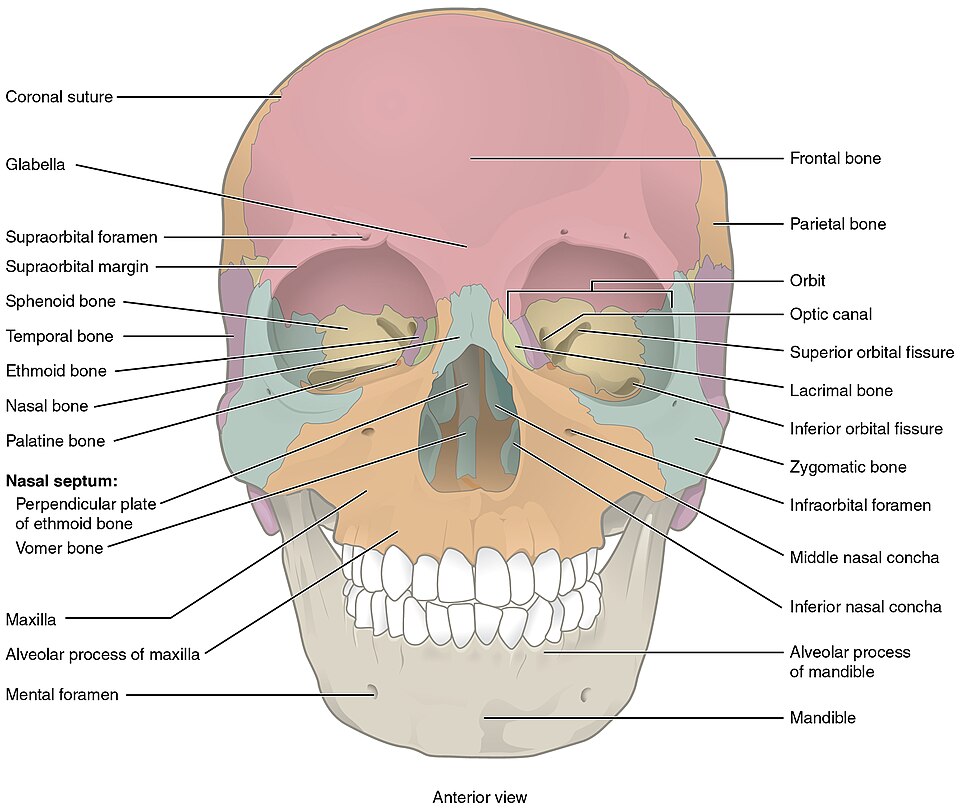

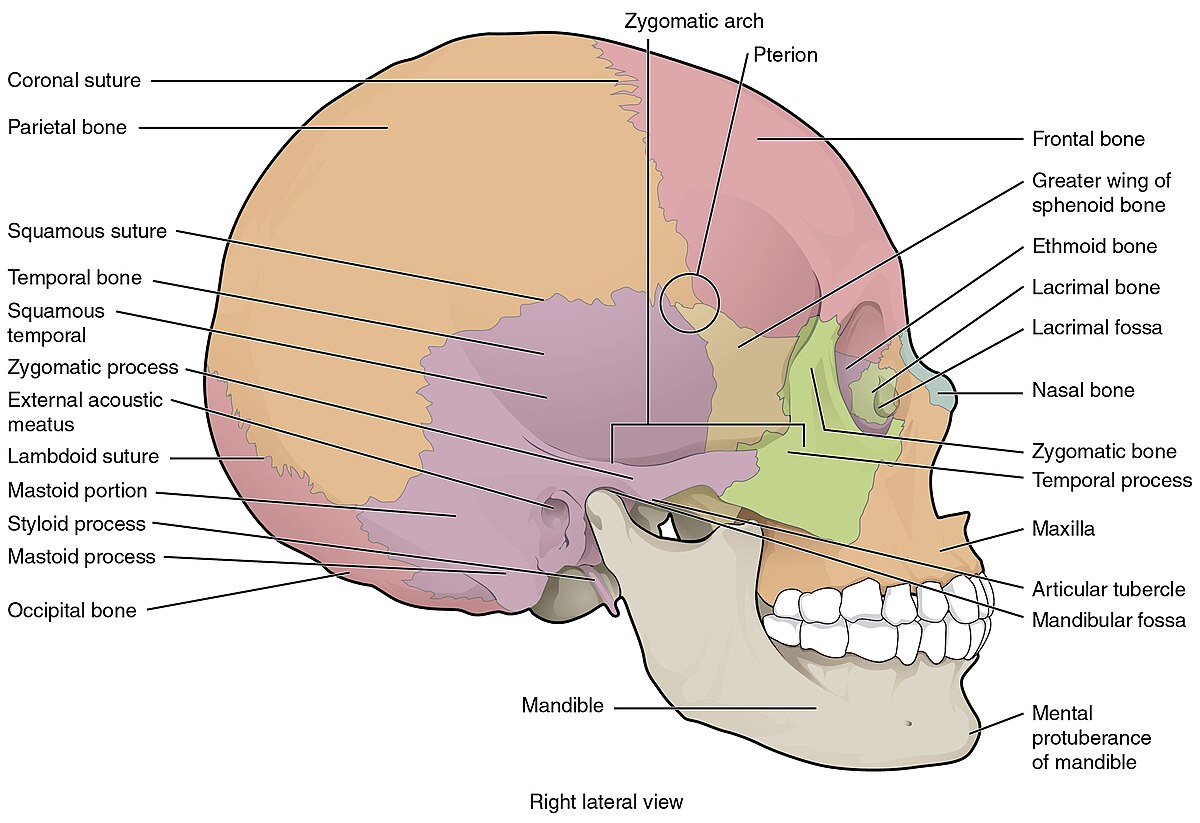

The cranium consists of eight bones, including the paired parietal and temporal bones and the unpaired frontal, occipital, sphenoid, and ethmoid bones. See Figure 6.21[2] for an anterior view of the cranial and facial bones.

The Cranial Bones

- Frontal Bone: A single bone superior to the eyes; the “forehead” bone.

- Parietal Bones: A pair of bones (left and right) on the upper sides of the skull above the ears.

- Temporal Bones: Two bones (left and right) on the lower sides of the skull surrounding the ears.

- External Auditory Canal (or External Auditory Meatus): Paired openings (left and right) in the temporal bones; the “ear canal.”

- Mastoid Process(es): A protrusion projecting down (inferiorly) off the temporal bone directly behind the external auditory meatus on the left and right sides. You can feel this bump if you reach behind the lower part of your ear.

- Styloid Process(es): A long, slender protrusion off of the temporal bone below the ear on the left and right side of the skull. It’s pointy and slender like a stylus.

- Zygomatic Process(es): A long, slender protrusion off of the temporal bone that forms part of the cheek.

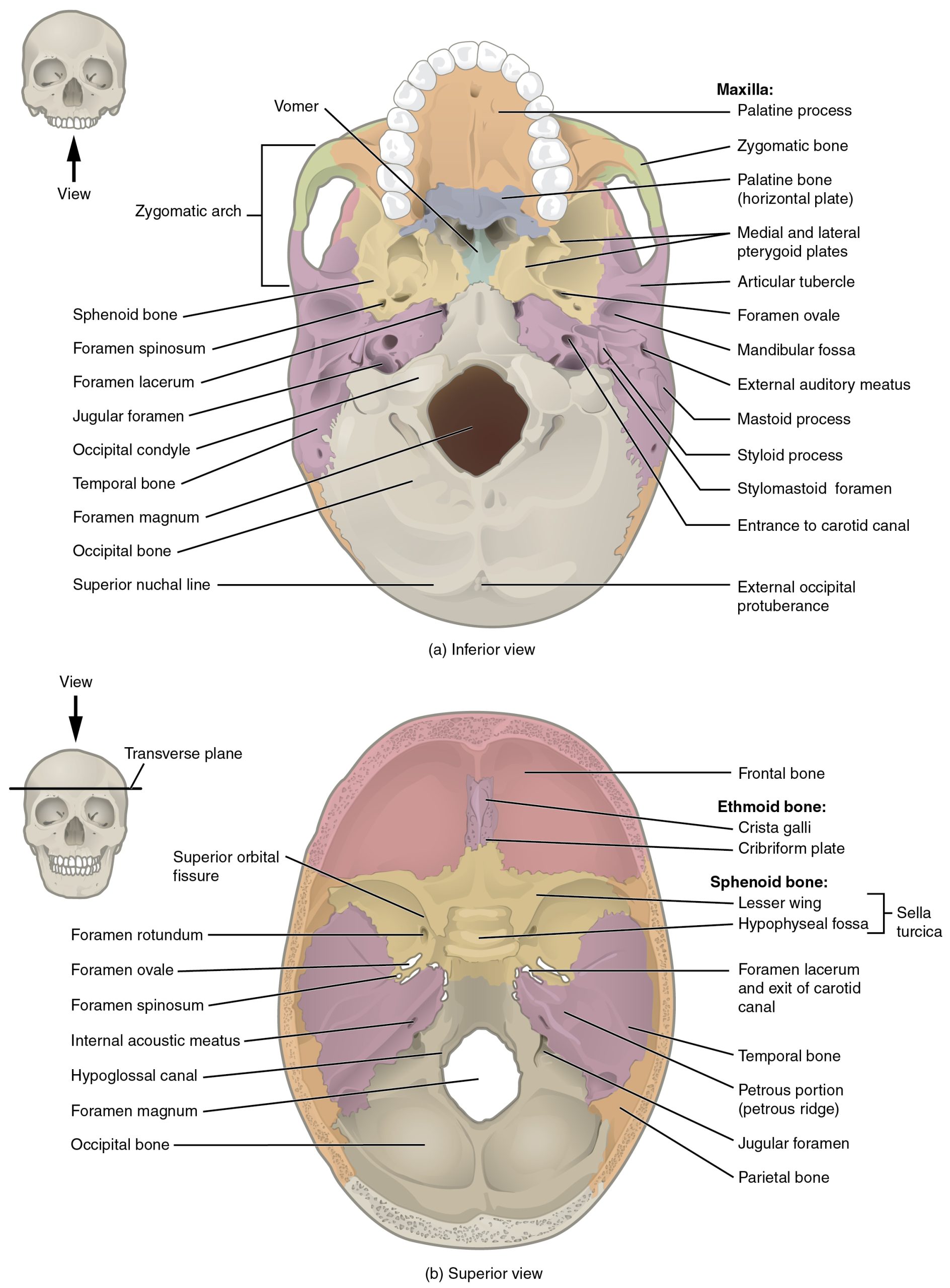

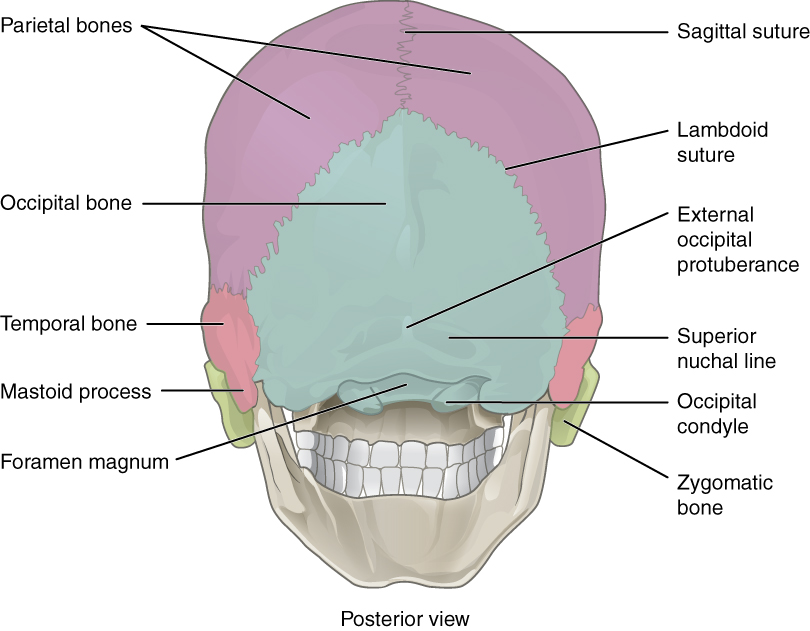

- Occipital Bone: A single bone forming the posterior side and base of the skull. See Figure 6.22[3] for an illustration of the occipital bone.

- Foramen Magnum: A large hole in the base of the occipital bone where the spinal cord joins the brain. See Figure 6.23[4] for an illustration showing the foramen magnum.

- Sphenoid Bone: A large single complex bone of the central skull forming the posterior side of the eye sockets and part of the base of the skull. The sphenoid bone serves as a “keystone” bone because it joins with almost every other bone of the skull. It has wings like a butterfly or bat. See Figure 6.23 for an illustration showing the sphenoid bone.

- Sella Turcica: A bony landmark in the sphenoid bone and also known as “Turkish saddle” due to its resemblance to a horse’s saddle. The pituitary gland sits in the sella turcica. See Figure 6.23 for an illustration containing the sella turcica.

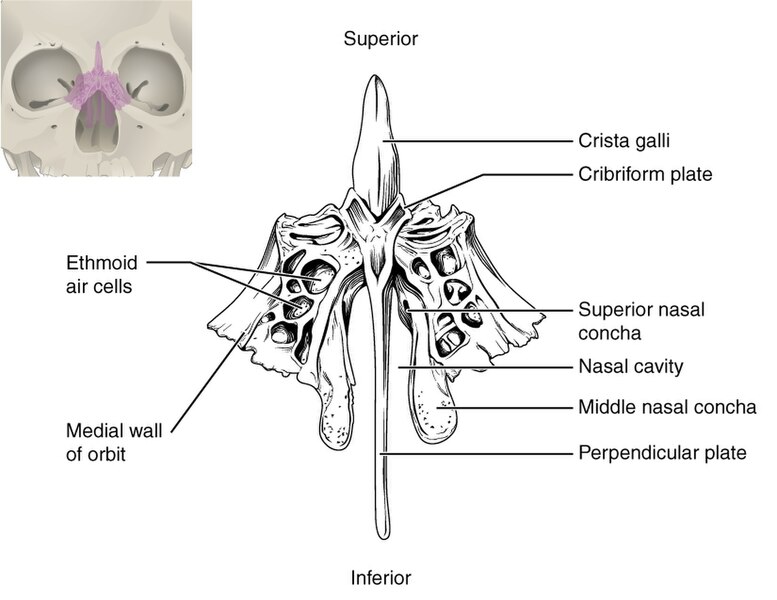

- Ethmoid Bone: A single, irregularly shaped bone forming part of the nose, medial side of the eye orbits, and base of the skull. See Figure 6.24[5] for an illustration of the ethmoid bone.

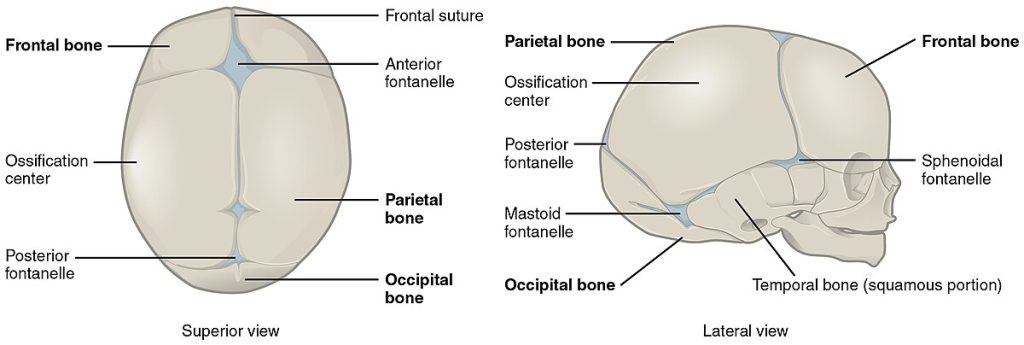

Fontanelles

As the bones grow in the fetal skull, they remain separated from each other by large areas of dense connective tissue membranes called fontanelles, commonly called “soft spots” on an infant’s head. See Figure 6.25[6] for an illustration of fontanelles. There are two major fontanelles called the anterior fontanelle and the posterior fontanelle. The anterior fontanelle is the larger fontanelle and is located on the top of the head, at the junction of the frontal and parietal bones. The posterior fontanelle is a smaller fontanelle and is located on the posterior side of the skull between the parietal and occipital bones. Fontanelles are important during childbirth because they allow the infant skull to compress and change shape as it squeezes through the birth canal. After birth, the fontanelles allow for continued growth and expansion of the skull as the brain enlarges. The fontanelles decrease in size and disappear by age 2. However, the skull bones remain separated from each other at the sutures that contain dense fibrous connective tissue, which allows for continued growth as the brain enlarges during childhood.

Sutures of the Skull

A suture is a fixed (immobile) joint between bones of the skull. The narrow gap between the bones is filled with dense, fibrous connective tissue that unites the bones. The sutures are not straight, but instead follow irregular, tightly twisting paths. These twisting lines tightly lock the bones together, adding strength to the skull for brain protection.

The five sutures of the skull are as follows:

- Coronal suture. The coronal suture runs from side to side across the top of the skull and joins the frontal bone to the parietal bones. See Figure 6.26[7] for an illustration of the lateral view of the skull depicting the coronal suture.

- Sagittal suture. The sagittal suture extends posteriorly from the coronal suture, along the midline at the top of the skull. See Figure 6.27 of an illustration of the posterior view of the skull to view the sagittal suture. It unites the right and left parietal bones. On the posterior skull, the sagittal suture ends by joining the lambdoid suture.

- Lambdoid suture. The lambdoid suture extends downward and laterally to either side from its junction with the sagittal suture. The lambdoid suture joins the occipital bone to the right and left parietal and temporal bones. This suture is named for its upside-down “V” shape, which resembles the capital letter version of the Greek letter lambda (Λ). See Figure 6.27[8] for an illustration of the posterior view of the skull depicting the lambdoid suture.

- Squamous suture. The squamous suture is located on each side of the skull. It unites the temporal bone with the parietal bone. See Figure 6.26 for an illustration of the lateral view of the skull depicting the squamous suture.

- Pterion: The pterion is a small, capital-H-shaped region that unites the frontal bone, parietal bone, temporal bone, and sphenoid bone. The bone here is thinner, making it the weakest part of the skull. See Figure 6.26 for an illustration of the lateral view of the skull with the pterion circled.

Paranasal Sinuses

The paranasal sinuses (also called sinuses) are hollow, air-filled spaces located within certain bones of the skull. All the sinuses connect with the nasal cavity (paranasal = “next to nasal cavity”) and are lined with nasal mucosa.

The sinuses reduce bone mass to lighten the skull and add resonance to the voice. This is most obvious when you have a cold or sinus congestion. Swelling of the mucosa and excess mucus production can block the narrow passageways between the sinuses and the nasal cavity, causing the voice to sound different. This blockage can also allow the sinuses to fill with fluid, producing pain and discomfort.

A paranasal sinus is named for the skull bone in which it resides:

- Frontal sinus: The frontal sinus is located just above the eyebrows in the frontal bone.

- Maxillary sinus: The maxillary sinuses are the largest sinus. They are paired and located within the right and left maxillary bones, where they occupy the area just below the eyes. The maxillary sinuses are most commonly involved during sinus infections because their location can make drainage difficult.

- Sphenoid sinus: The sphenoid sinus is a single sinus located within the body of the sphenoid bone near the sella turcica.

- Ethmoid air cells: The ethmoid bone contains small spaces called ethmoid air cells separated by very thin bony walls.

See Figure 6.28[9] for an illustration of the paranasal sinuses.

Major Facial Bones and Features:

The facial bones form the upper and lower jaws, the nose, nasal cavity and nasal septum, and the eye orbits. The facial bones include 14 bones, with six paired bones and two unpaired bones. Refer back to Figure 6.20 of the illustration of anterior skull to view the following facial bones:

- Zygomatic bones: Pair of bones on the right and left side of the anterior face; also called the “cheekbones.”

- Maxillae: Pair of fused bones on the right and left side of the face forming the upper jaw and hard palate (roof of the mouth). If these bones don’t join together correctly, a person will have a cleft palate.

- Palatine bones: Pair of fused L-shaped bones on the right and left side of the face that form part of the hard palate, walls of the nasal cavity, and the orbital floor of the eye.

- Nasal bones: Pair of fused bones on the right and left side of the face that form the bridge of the nose.

- Lacrimal bones: Pair of bones on the right and left side of the face that form the walls of the medial orbit (eye socket).

- Inferior nasal conchae (Turbinates): Group of irregularly shaped bones (right and left) that form the lower lateral (outside) walls of the nasal cavity.

- Vomer: Thin bone that forms the nasal septum, which separates the left and right nostrils.

- Mandible: Bone forming the lower jawbone. It is the only movable bone of the skull.

The temporomandibular joint (TMJ) is a hingelike joint between the temporal bone and the mandible that allows for the opening, closing, protrusion, retraction, and lateral movement of the lower jaw. Refer back to Figure 6.26 of the illustration of the lateral skull to view the temporomandibular joint.

Hyoid Bone

The hyoid bone is an independent bone that doesn’t connect to any other bone and is not considered part of the skull. It is a small U-shaped bone located in the upper neck. The hyoid serves as the base for the tongue above and is attached to the voice box below. Movements of the hyoid are coordinated with movements of the tongue, voice box, and throat during swallowing and speaking. See Figure 6.29[10] for an illustration of the hyoid bone.

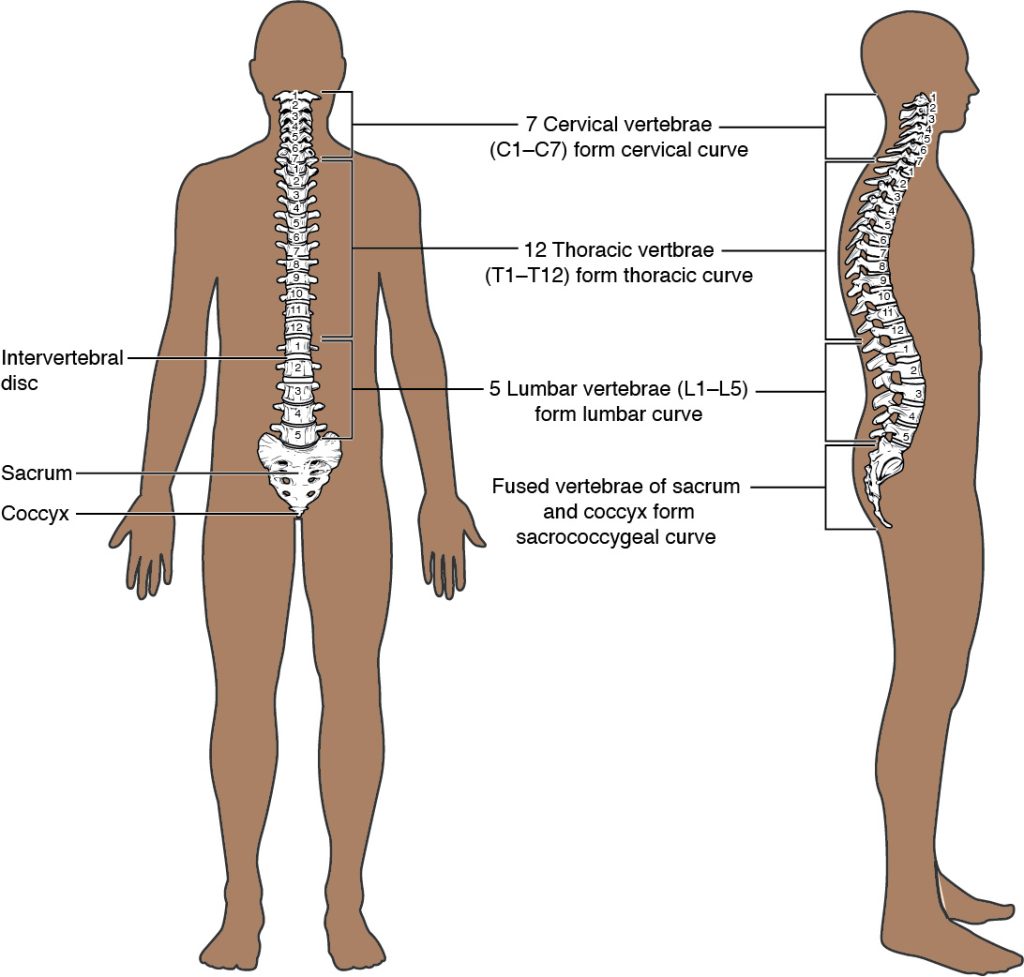

Vertebral Column and Vertebrae

The vertebral column (also referred to as the spinal column) is a flexible column of bones that supports the head, neck, and body and protects the spinal cord. It is made up of bones called vertebrae (vertebra = singular) that are separated by discs of fibrocartilage called intervertebral discs. The spinal cord runs through the center of the vertebrae. See Figure 6.30[11] for an illustration of the vertebral column.

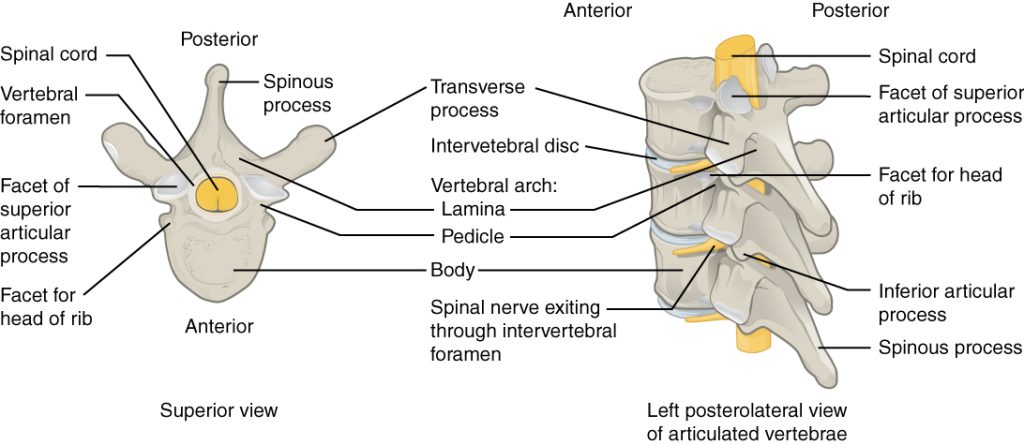

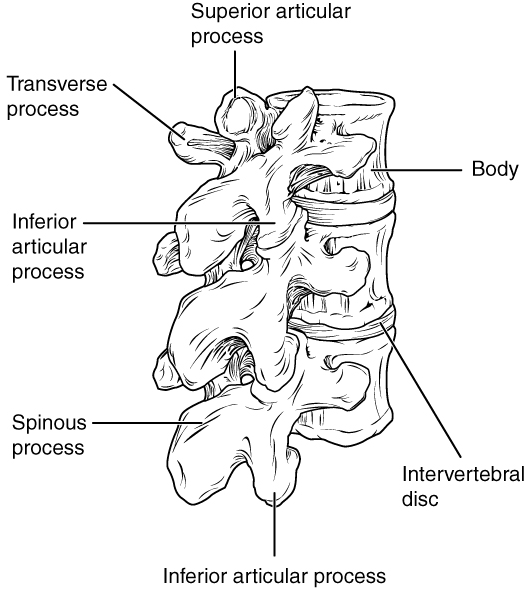

General Structure of a Vertebra

Within the different regions of the vertebral column, vertebrae vary in size and shape, but they all follow a similar structural pattern. A typical vertebra consists of a body, a vertebral arch, and seven processes.

- The body is the anterior portion of each vertebra and is the part that supports body weight. Because of this, the vertebral bodies increase in size and thickness moving down the vertebral column. In between the bodies of the vertebrae are where the intervertebral discs are located. They help form joints connecting individual vertebrae together in the vertebral column.

- The vertebral arch forms the posterior portion of each vertebra. The large opening between the vertebral arch and body is the vertebral foramen (plural = foramina), which contains the spinal cord. The vertebral foramina of all the vertebrae align to form the vertebral (spinal) canal, which serves as the bony protection and passageway for the spinal cord down the back. When the vertebrae are aligned together in the vertebral column, notches are found between the vertebrae. Each notch is called an intervertebral foramen and forms an opening through which a spinal nerve travels through the vertebral column.

- Seven processes arise from the vertebral arch.

See Figure 6.31[12] for an illustration of the major parts of a vertebra.

Seven processes of a vertebrae include the following:

- Transverse process: A pair of processes projecting laterally on each side, serving as important muscle attachment sites.

- Spinous process: A single process that projects posteriorly at the midline. These processes can easily be felt as a series of bumps just under the skin down the middle of the back. The spinous process also serves as important muscle attachment sites.

- Superior articular process: Pair of processes that extend or face upward.

- Inferior articular process: Pair of processes that face or project downward on each side of a vertebrae.

See Figure 6.32[13] for an illustration of the seven vertebral processes. The paired superior articular processes of one vertebra join with the corresponding paired inferior articular processes from the next higher vertebra. These junctions form slightly moveable joints between the adjacent vertebrae. The shape and orientation of the articular processes vary in different regions of the vertebral column and play a major role in determining the type and range of motion available in each region.

Vertebrae Regions

The vertebrae are divided into five regions called the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, sacral, and coccyx. Refer back Figure 6.30 for an illustration of vertebra regions. The vertebrae in each of these regions are further described in the following subsections.

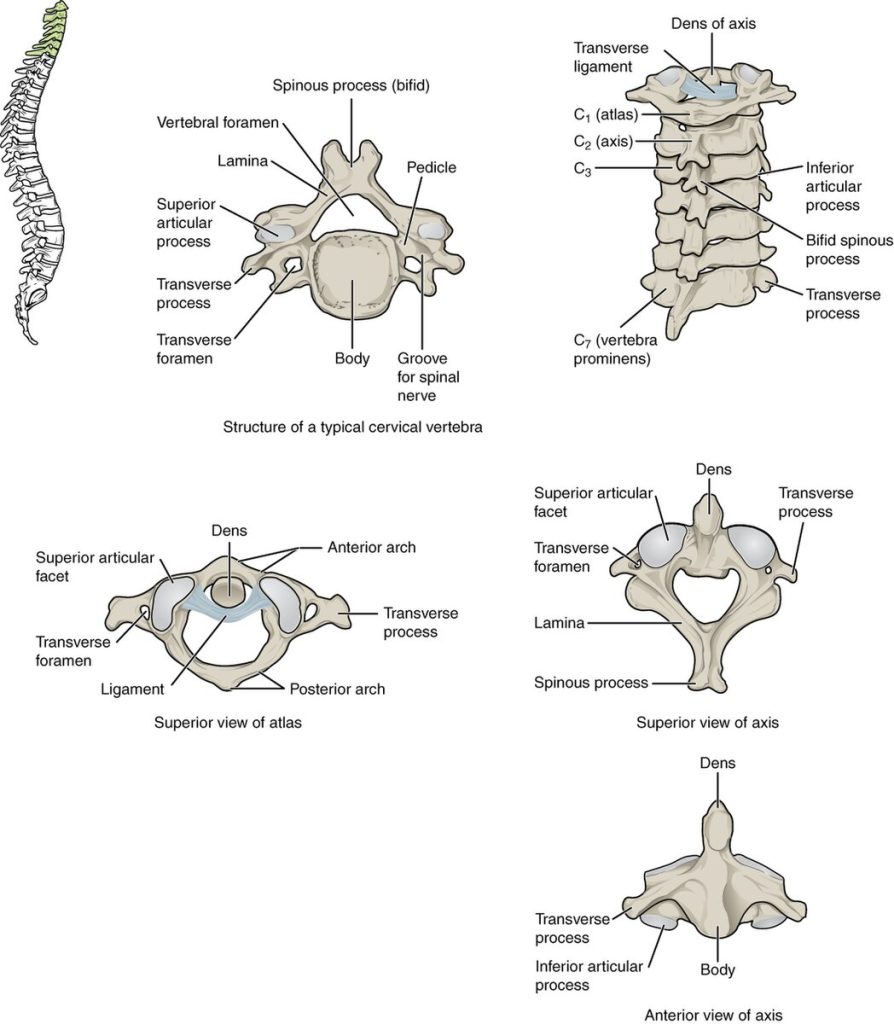

Cervical Vertebrae

The first seven cervical vertebrae in the neck region are designated by the letter “C” and are numbered C1 to C7. Cervical vertebrae have a small body because they carry the least amount of body weight. Cervical vertebrae usually have a bifid (Y-shaped) spinous process. You can find these vertebrae by running your finger down the midline of the posterior neck until you encounter the prominent C7 spine located at the base of the neck. Each transverse process also has an opening called the transverse foramen. An important artery that supplies the brain ascends up the neck by passing through these openings. The first two cervical vertebrae have their own names called atlas and axis:

- Atlas (C1): The first cervical vertebrae called the atlas supports the skull on top of the vertebral column. (In Greek mythology, Atlas was the god who supported the heavens on his shoulders). The C1 vertebra does not have a body or spinous process. Instead, it is ring-shaped with transverse processes extending laterally.

- Axis (C2): The second cervical vertebrae called the axis serves as the axis for rotation when turning the head toward the right or left. The axis resembles typical cervical vertebrae in most respects, but is easily distinguished by the dens (odontoid process), a bony projection that extends upward from the vertebral body.

See Figure 6.33[14] for an illustration of the cervical vertebrae.

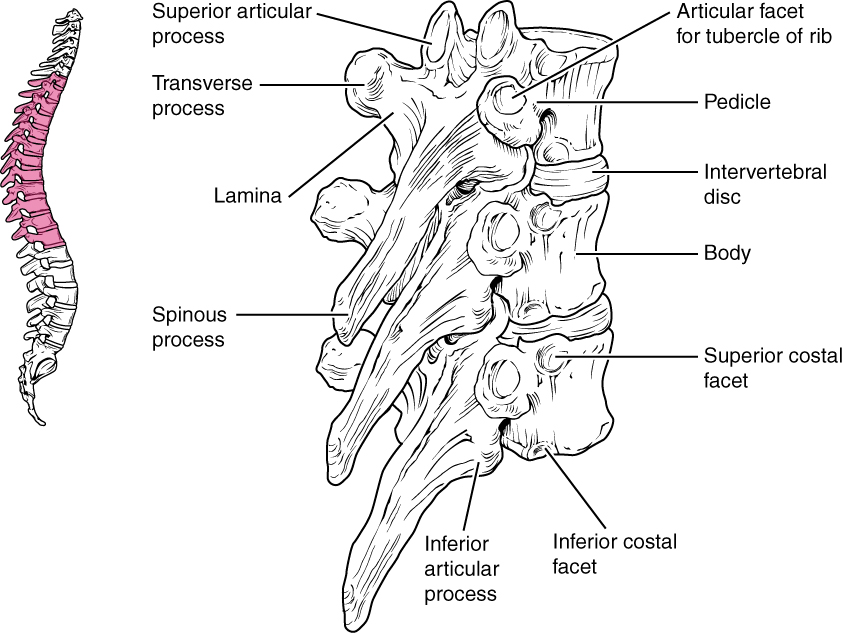

Thoracic Vertebrae

Twelve thoracic vertebrae form the outward curvature of the spine and the back of the thoracic cage. These vertebrae are designated by the letter “T” and are numbered T1 to T12. The bodies of the thoracic vertebrae are larger than those of cervical vertebrae. The spinous process is long and has a pronounced downward angle that causes it to overlap the next inferior vertebra. Thoracic vertebrae have facets on their transverse processes where ribs attach. See Figure 6.34[15] for an illustration of a thoracic vertebra.

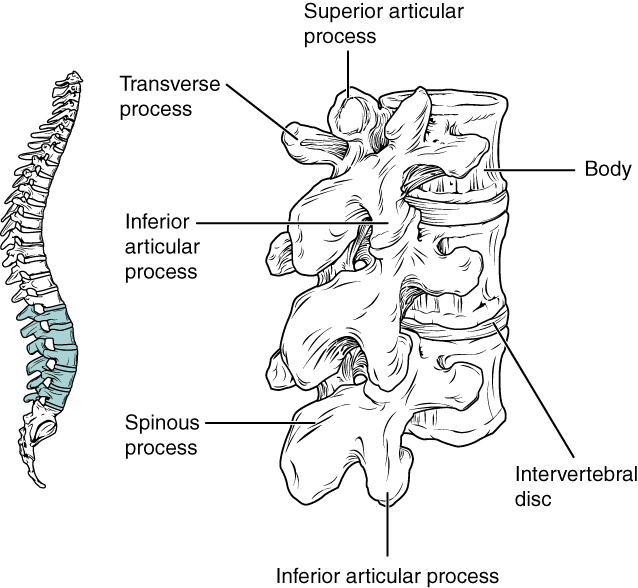

Lumbar Vertebrae

There are five vertebrae that form the inner curvature of the lower spine. They form the lower back. These vertebrae are designated with the letter “L” and are numbered L1 to L5. Lumbar vertebrae carry the most body weight, so they are larger and have a thicker vertebral body. They have short transverse processes and a short, rounded spinous process. The articular processes are large, with the superior process facing medially and the inferior facing laterally. See Figure 6.35[16] for an illustration of the lumbar vertebrae.

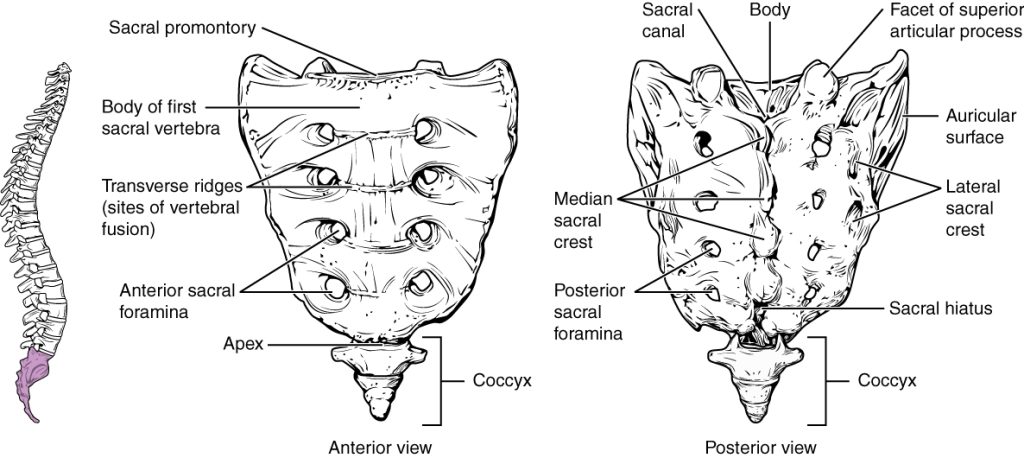

Sacral Vertebrae (Sacrum)

The sacrum is a triangular-shaped bone that is thick and wide across the top where it is weight bearing and then tapers down to the inferior, non-weight bearing apex. It is formed by the fusion of five sacral vertebrae, a process that does not begin until after the age of 20. See Figure 6.36[17] for an illustration of the sacrum.

Coccyx

The coccyx (commonly referred to as the tailbone) is formed by the fusion of four very small coccygeal vertebrae. It articulates (forms a joint) with the inferior tip of the sacrum. It is not weight bearing in the standing position but may receive some body weight when sitting. Review Figure 6.36 for an illustration of the coccyx.

Vertebral Curvatures

The adult vertebral column does not form a straight line but instead has four curvatures. (Review Figure 6.30 of the vertebral column for an illustration of these curvatures). These curves increase the vertebral column’s strength, flexibility, and ability to absorb shock. When the load on the spine is increased, such as when carrying a heavy backpack for example, the curvatures increase in depth (become more curved) to accommodate the extra weight. They then spring back when the weight is removed.

The four adult curvatures are classified as either primary or secondary curvatures. Primary curves are retained from the original fetal curvature, whereas secondary curvatures develop after birth. The vertebral column has two primary curvatures (thoracic and sacrococcygeal curves) and two secondary curvatures (cervical and lumbar curves). Read about medical disorders with abnormal curvatures in the “Skeletal System Disorders” section.

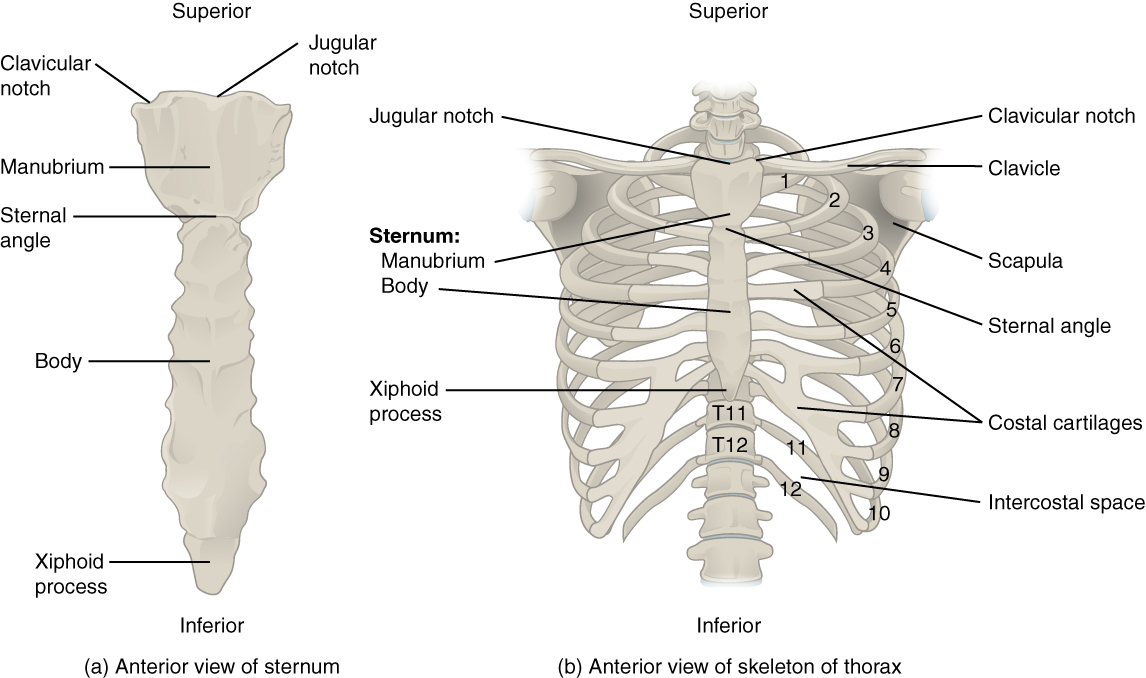

Thoracic Cage

The thoracic cage (commonly called the rib cage) forms the thorax (chest), protecting the heart and lungs. It consists of the sternum and 12 pairs of ribs. The ribs are connected posteriorly to the 12 thoracic vertebrae. See Figure 6.37[18] for an illustration of the thoracic cage.

Sternum

The sternum (commonly called the breastbone) is divided into three parts:

- Manubrium: The upper portion of the sternum

- Body: The middle portion of the sternum

- Xiphoid process: The lower portion of the sternum made of cartilage early in life but gradually ossifies starting in middle age.

Ribs

There are 12 pairs of ribs numbered 1–12 in accordance with the thoracic vertebrae. Each rib is a curved, flattened bone that makes up part of the wall of the thorax or chest cavity. They meet posteriorly with the T1–T12 thoracic vertebrae, and most attach anteriorly with cartilage to the sternum.

The 12 pairs of ribs can be classified as true ribs, false ribs, and floating ribs:

- True ribs: Ribs 1-7 are attached directly to the anterior sternum by costal (rib) cartilage.

- False ribs: Ribs 8, 9, and 10 are attached to the costal cartilage of the seventh rib (and are, therefore, indirectly attached to the sternum).

- Floating ribs: Ribs 11 and 12 are not attached to the sternum at all.

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Medical terminology 2e. Open RN | WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/medterm/ ↵

- “704_Skull-01” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “Occipital_bone_lateral.png” by Anatomography is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.1 Japan ↵

- “707_Superior-Inferior_View_of_Skull_Base-01” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “710_Ethmoid_Bone” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “702_Newborn_Skull-01” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “705_Lateral_View_of_Skull-01” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “730_Posterior_View_Skull” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “724_Paranasal_Sinuses” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “aee59361e79d7fd9c4373ca4f9a12b3dc1eab2d8” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/7-2-the-skull ↵

- “408a4ed7f3a629c9a7e2e08b8544ca3d5ff055c3” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/7-3-the-vertebral-column ↵

- “718_Vertebra” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- This image is derived from “725_Lumbar_Vertebrae” by OpenStax College and licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “723_Cervical_Vertebrae” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “719_Thoracic_Vertebra” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “725_Lumbar_Vertebrae” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “720_Sacrum_and_Coccyx” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “721_Rib_Cage” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

A single bone superior to the eyes, the “forehead” bone.

A pair of bones (left and right) on the upper sides of the skull, above the ears.

Two bones (left and right) on the lower sides of the skull, surrounding the ears

Paired openings (left and right) in the temporal bones, the “ear canal”.

A protrusion projecting down (inferiorly) off the temporal bone directly behind the external auditory meatus on the left and right sides. You can feel this bump if you reach behind the lower part of your ear.

A long, slender protrusion off of the temporal bone below the ear on the left and right side of the skull.

A long, slender protrusion off of the temporal bone that forms part of the cheek.

A single bone forming the posterior side and base of the skull.

A large hole in the base of the occipital bone where the spinal cord joins the brain.

A large single complex bone of the central skull forming the posterior side of the eye sockets and part of the base of the skull.

A bony landmark in the sphenoid bone, also known as “Turkish saddle” due to its resemblance to a horse’s saddle.

A single, irregularly shaped bone forming part of the nose, medial side of the eye orbits, and base of the skull. See Figure 6.23 for an illustration of the ethmoid bone.

Soft spots on a baby’s skull where the bones have not yet fully fused. These flexible gaps are covered by a tough membrane and allow for the baby’s brain to grow and for the skull to compress slightly during childbirth.

The largest fontanelle and is located on the top of the head, at the junction of the frontal and parietal bones.

A smaller fontanelle and is located on the posterior side of the skull between the parietal and occipital bones.

A fixed (immobile) joint between bones of the skull.

Suture which runs from side to side across the top of the skull and joins the frontal bone to the parietal bones.

A suture which extends posteriorly from the coronal suture, along the midline at the top of the skull uniting the right and left parietal bones.

Suture which extends downward and laterally to either side from its junction with the sagittal suture, joins the occipital bone to the right and left parietal and temporal bones.

Suture located on each side of the skull. It unites the temporal bone with the parietal bone.

A small, capital-H-shaped region that unites the frontal bone, parietal bone, temporal bone, and sphenoid bone.

Hollow, air-filled spaces located within certain bones of the skull.

Sinus is located just above the eyebrows in the frontal bone

The largest sinus located within the right and left maxillary bones.

Single sinus located within the body of the sphenoid bone near the sella turcica

Small spaces separated by very thin bony walls located in the ethmoid bone.

Pair of bones on the right and left side of the anterior face, the “cheekbones.”

Pair of fused bones on the right and left side of the face forming the upper jaw and hard palate (roof of the mouth).

Pair of fused L-shaped bones on the right and left side of the face that form part of the hard palate, walls of the nasal cavity, and the orbital floor of the eye.

Pair of fused bones on the right and left side of the face that form the bridge of the nose.

Pair of bones on the right and left side of the face that form the walls of the medial orbit (eye socket).

Group of irregularly shaped bones (right and left) that form the lower lateral (outside) walls of the nasal cavity.

Thin bone that forms the nasal septum which separates the left and right nostrils.

Bone forming the lower jawbone. It is the only movable bone of the skull.

A hingelike joint between the temporal bone and the mandible that allows for the opening, closing, protrusion, retraction, and lateral movement of the lower jaw.

An independent bone that doesn’t connect to any other bone and is not considered part of the skull.

A flexible column of bones that support the head, neck, and body and protects the spinal cord, also known as the spinal column.

A flexible column of bones that support the head, neck, and body and protects the spinal cord, also known as the vertebral column.

Bones that in the head, neck, and body that protect the spinal cord.

The soft, cushion-like pads located between the vertebrae in the spine.

The part of a vertebra that forms the back portion of the vertebral foramen, which is the opening through which the spinal cord passes.

The large opening between the vertebral arch and body of each vertebra that contains the spinal cord.

The tunnel-like passage that runs through the vertebral column and houses the spinal cord and its protective coverings (meninges), along with blood vessels and spinal nerves.

The opening or gap between two vertebrae where spinal nerves exit the spinal column.

A pair of processes projecting laterally on each side serving as important muscle attachment sites.

A single process that projects posteriorly at the midline. These processes can easily be felt as a series of bumps just under the skin down the middle of the back.

Pair of processes that extend or face upward.

Pair of processes that face or project downward on each side of a vertebrae.

The opening within the transverse process.

The first cervical vertebrae which supports the skull on top of the vertebral column.

The second cervical vertebrae which serves as the axis for rotation when turning the head toward the right or left.

A bony projection that extends upward from the vertebral body, also known as the odontoid process.

Areas on the transverse processes of the thoracic vertebrae where the ribs attach.

A triangular-shaped bone that is thick and wide across the top where it is weight bearing and then tapers down to the inferior, non-weight bearing apex.

Commonly referred to as the tailbone, area formed by the fusion of four very small coccygeal vertebrae.

A flat T-shaped bone located in the center of the chest, commonly called the breastbone.

The upper portion of the sternum.

The middle portion of the sternum.

The lower portion of the sternum made of cartilage early in life but which gradually ossifies starting in middle age.

Ribs 1-7 are attached directly to the anterior sternum by costal (rib) cartilage.

Ribs 8, 9, and 10 are attached to the costal cartilage of the seventh rib (and are therefore indirectly attached to the sternum)

Ribs 11 and 12 are not attached to the sternum at all.