5.3 Anatomy of the Integumentary System

Anatomy of the Integumentary System[1]

Layers of the Skin

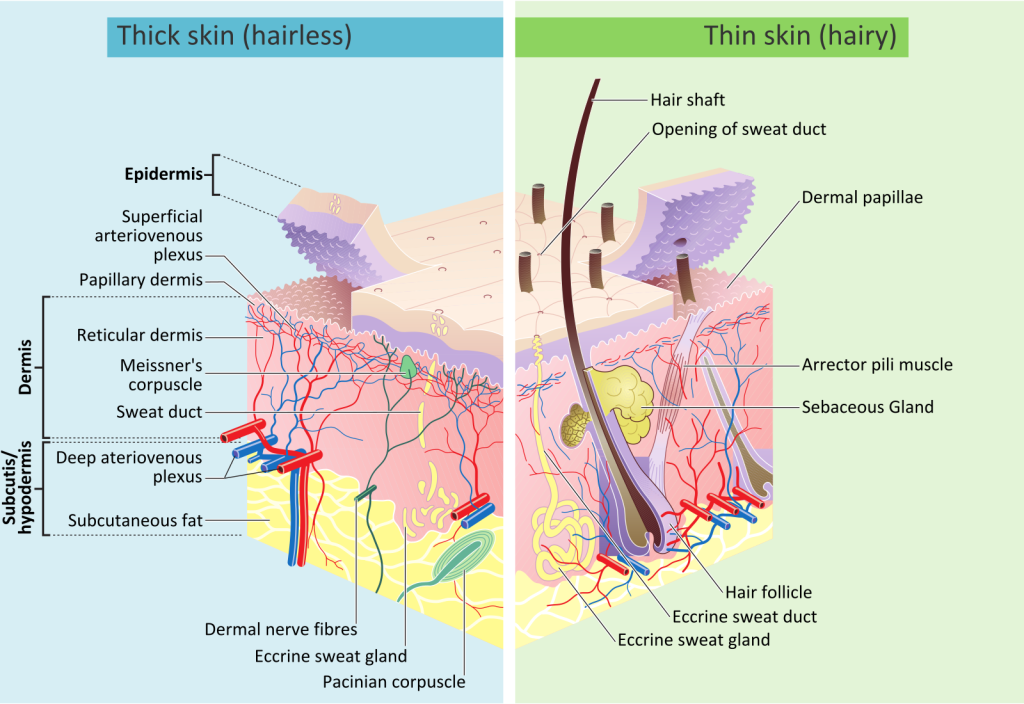

The skin is made up of multiple layers of cells and tissues that are anchored to deeper structures by connective tissue. The three main layers found in the skin are as follows:

- Epidermis

- Dermis

- Hypodermis (also called the subcutaneous layer)

See Figure 5.2[2] for an illustration of these three main layers of the skin.

Epidermis

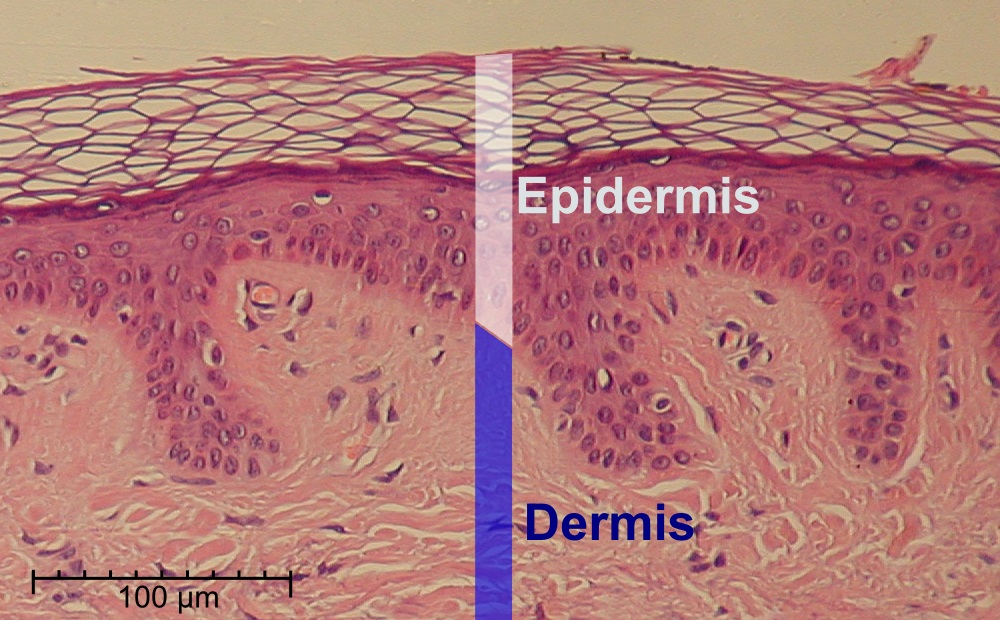

The epidermis is the top layer of skin exposed to the outside world. It is composed of stratified squamous epithelium. The epidermis is avascular, meaning it does not have a blood supply. See Figure 5.3[3] for an image of the epidermis.

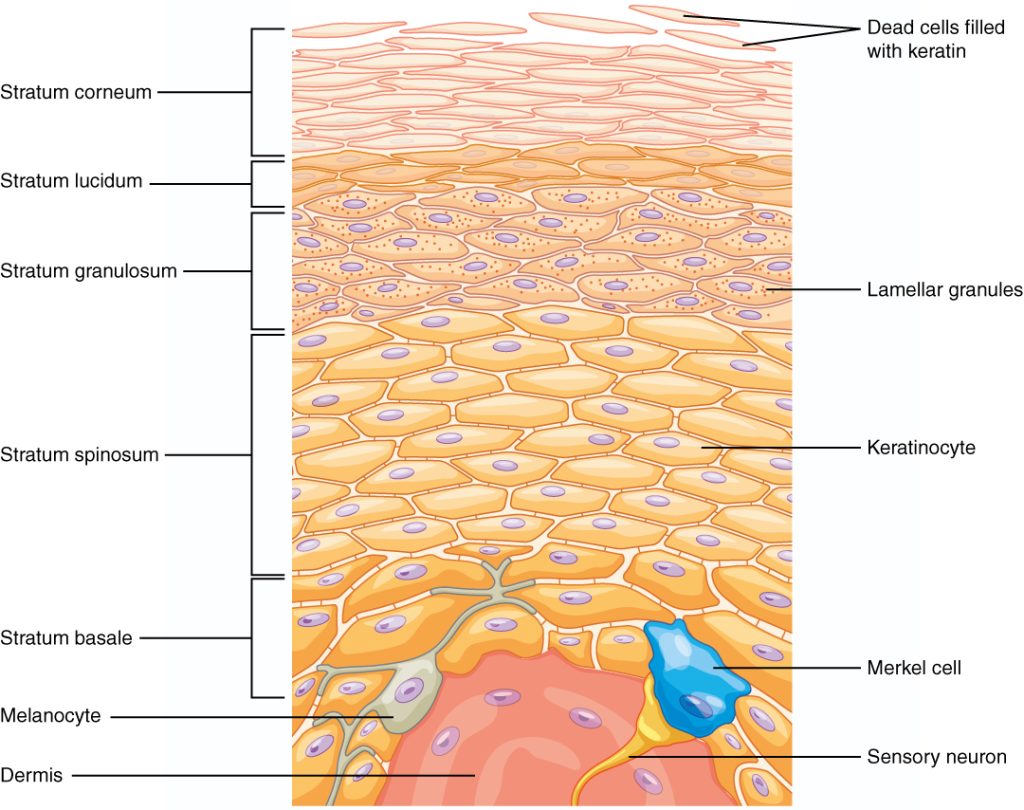

Layers of the Epidermis

The epidermis is composed of four to five layers of epithelial cells, depending on its location in the body. Skin that has four layers of cells is referred to as “thin skin.” From superficial to deep, these layers are the stratum corneum, stratum granulosum, stratum spinosum, and stratum basale. Most skin in the body is thin skin. “Thick skin” is found only on the palms of the hands, fingertips, and the soles of the feet. It has a fifth layer, called the stratum lucidum, located between the stratum corneum and the stratum granulosum. The cells in all of the layers except the stratum basale are called keratinocytes. A keratinocyte is a cell that makes and stores the protein keratin. Keratin is a protein that gives hair, nails, and skin their hardiness and water-resistant properties. The keratinocytes in the stratum corneum are dead and regularly slough away, being replaced by cells from the deeper layers. See Figure 5.4[4] for an illustration of the layers of the epidermis.

Stratum Corneum

The stratum corneum is the most superficial layer of the epidermis that is exposed to the outside environment. The name is based on cornification (increased keratinization) of the cells in this layer. There are 15 to 30 layers of dead cells in the stratum corneum. The dry, dead layers prevent microbes from getting into the body and prevent dehydration of underlying tissues. This layer also provides protection from injury to the underlying layers. Cells in this layer are continuously shed and replaced by cells pushed up from the deeper layers of the epidermis.

Stratum Lucidum

Stratum lucidum is a smooth, translucent (clear) layer of the epidermis located just below the stratum corneum. This thin layer of cells is found only in areas of the body with thick skin: the palms of the hands, the fingertips, and the soles of the feet. The keratinocytes that compose the stratum lucidum are dead, flattened cells.

Stratum Granulosum

The stratum granulosum has a grainy appearance caused by changes to the keratinocytes as they are pushed up through the epidermis. This layer is three to five cell layers thick, and the cells are flatter with thick cell membranes. They generate large amounts of keratin, allowing the stratum granulosum layer to repel water. Keratinocytes start to die in this layer because they are getting too far away from the blood supply located deeper in the skin.

Stratum Spinosum

The stratum spinosum is named for its spiny appearance due to protruding cell processes that connect the cells in this layer together. (This spiny appearance is only seen when the epidermis is stained). The stratum spinosum has eight to ten layers of keratinocytes, as well as Langerhans cells, a type of macrophage that ingests bacteria, foreign particles, and even damaged cells. The keratinocytes make keratin and release a water-repelling substance that helps prevent water loss, making the skin relatively waterproof. The stratum spinosum provides strength and flexibility to the skin.

Stratum Basale

The stratum basale (also called the stratum germinativum) is the deepest epidermal layer. The cells in the stratum basale attach to the dermis with collagen fibers, referred to as the basement membrane. The stratum basale is a single layer of cells primarily made of basal cells. A basal cell is a stem cell that makes the keratinocytes of the epidermis. All keratinocytes are produced from this single layer of cells, which are constantly going through mitosis to produce new cells. As new cells are formed, the existing cells are pushed up and away from the stratum basale.

Two other cell types found among the basal cells in the stratum basale are merkel cells and melanocytes.

- Merkel cells function as a receptor to perceive touch. These cells are especially abundant on the surfaces of the hands and feet.

- Melanocytes produce the pigment melanin. Melanin gives hair and skin its color and also helps protect cells of the epidermis from ultraviolet (UV) radiation damage.

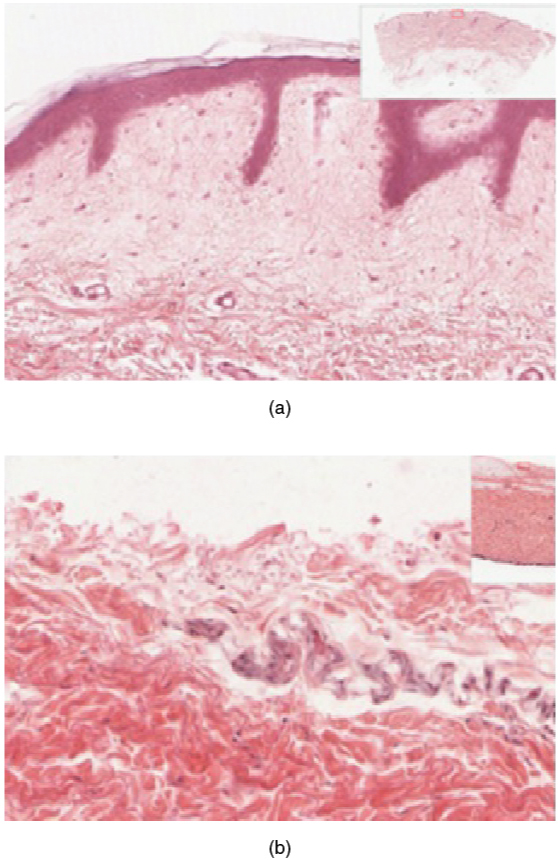

Thin and Thick Skin

Thin skin covers most areas of the body (except for the soles, fingertips, and palms). Thin skin is missing the stratum lucidum layer, so it contains four layers of epidermal cells. Hair, sebaceous glands, and arrector pili muscles are also found in thin skin.

Thick skin is found on the soles of the feet, fingertips, and palms of the hands. The epidermis in these areas is thicker because these body parts are used continuously and require extra protection. Thick skin contains all five layers of epidermal cells. Hair and its associated structures (sebaceous glands and arrector pili) are absent in thick skin.

See Figure 5.5[5] for images of thin and thick skin.

Dermis

Deep to the epidermis layer is the dermis (where derma- means “skin”). Sometimes referred to as the “true skin,” the dermis is the skin layer that contains blood and lymph vessels, nerves, and other structures such as hair follicles and sweat glands.

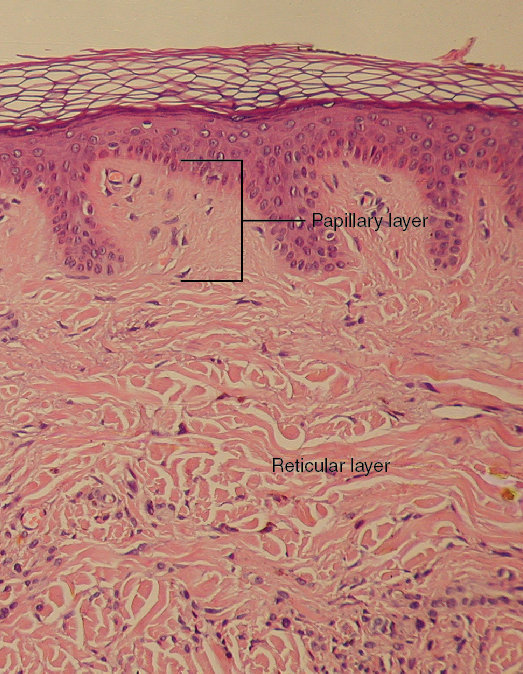

The dermis is made up of two regions of connective tissue called the papillary and reticular layers. See Figure 5.6[6] for an image of the layers of the dermis.

Papillary Layer

The papillary layer of the dermis is made of loose, areolar connective tissue, which means the collagen and elastin fibers of this layer form a loose mesh. This superficial layer of the dermis projects up into the stratum basale of the epidermis to form finger-like dermal papillae, resulting in the formation of the ridges on fingers that create fingerprints. Fingerprints are unique to each individual and can be used for forensic analysis, as the patterns do not change with the growth and aging processes.

Other important structures found in the papillary layer include fibroblasts, a small number of adipocytes (fat cells), an abundance of small blood vessels, and phagocytes to help fight bacteria or other pathogens that have invaded the skin. This layer also contains lymphatic capillaries, nerve fibers, and light touch receptors called Meissner corpuscles.

Reticular Layer

Deep to the papillary layer of the dermis is the much thicker reticular layer that is composed of dense irregular connective tissue. This layer contains many blood vessels and has a rich nerve supply. In addition, hair follicles, sebaceous (oil) glands, and sudoriferous (sweat) glands are found in this layer.

The reticular layer appears reticulated (net-like) due to a tight mesh of fibers, including elastin fibers and collagen fibers. Elastin fibers provide some elasticity to the skin and enable movement. Collagen fibers provide structure and strength. Collagen also binds water to keep the skin hydrated.

Hypodermis

The hypodermis (also called the subcutaneous layer or superficial fascia) is the third layer of the skin directly below the dermis. It connects the skin to the underlying fascia (fibrous tissue) of the bones and muscles. The hypodermis consists of well-vascularized, loose, areolar connective tissue and adipose tissue that stores fat and provides insulation and cushioning.

Accessory Structures of the Skin

The skin has a variety of structures that are essential for normal functioning and include the hair, nails, sudoriferous (sweat) glands, sebaceous (oil) glands, ceruminous glands, and sensory receptors.

Hair

Strands of hair originate in the dermis in a structure called the hair follicle. Hair is primarily made of dead, keratinized cells growing out of the epidermis. Hair grows continuously but is eventually shed and replaced by new hair. Similar to the skin, hair gets its color from the pigment melanin, and different hair color results from differences in the type of melanin. As a person ages, the melanin production decreases, and hair tends to lose its color and becomes gray and/or white.

Hair has two main parts called the hair shaft and the hair root:

- Hair shaft: The hair shaft is the part of the hair that protrudes from the surface of the skin.

- Hair root: The hair root is anchored in the follicle in the dermis. Each hair root is connected to a smooth muscle called the arrector pili muscle. When stimulated, these smooth muscles make the hair shaft “stand up,” creating what you know as “goose bumps.”

Refer back to Figure 5.2 for an illustration of hair and the arrector pili muscle.

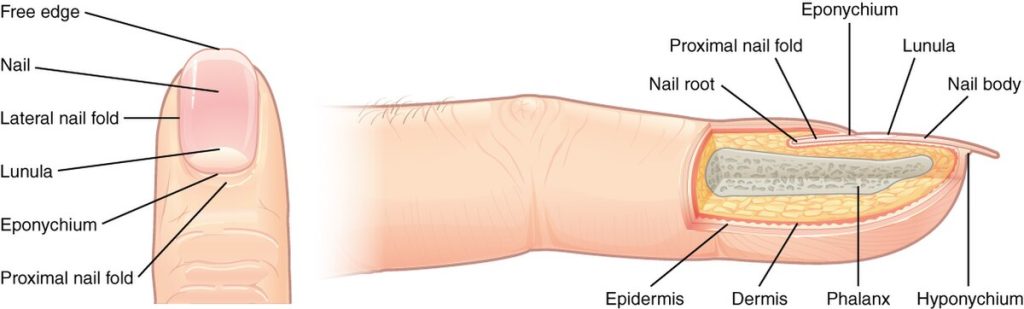

Nails

The fingernails and toenails are made up of several structures:

- Nail bed: The nail bed is a specialized structure of the epidermis found at the tips of our fingers and toes. The nail bed is rich in blood vessels, making it appear pink, except at the base, where a thick layer of epithelium over the nail matrix forms a crescent-shaped region called the lunula (the “little moon”).

- Nail body: The nail body is made up of densely packed dead keratinocytes formed on the nail bed. It protects the tips of our fingers and toes, and the free edge (the white part of the nail that extends beyond the nail bed) can also help the fingers pick up small objects.

- Nail root: The nail root contains dividing cells from the stratum basale that allows the nail to grow continuously.

- Cuticle: The nail cuticle, also called the eponychium, is a small area of epidermis at the base of the nail.

- Hyponychium: The hyponychium is the area beneath the free edge of the nail and is made up of a thickened layer of stratum corneum.

See Figure 5.7[7] for an illustration of nail structures.

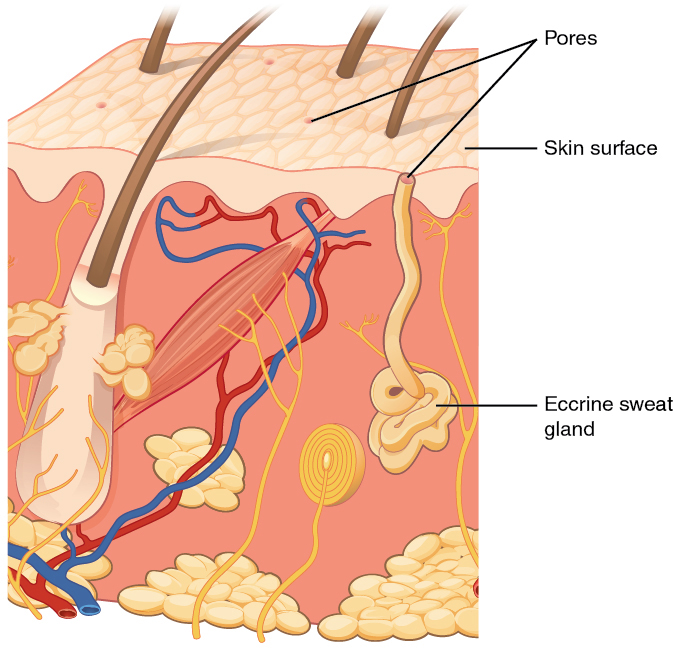

Sudoriferous Glands

There are two types of sudoriferous (sweat) glands found in the human body called eccrine sweat glands and apocrine sweat glands, each secreting slightly different products.

Eccrine Sweat Glands

An eccrine sweat gland produces sweat for thermoregulation to help cool the body. These glands are found all over the skin’s surface but are especially abundant on the palms of the hand, the soles of the feet, and the forehead. This type of sweat is composed mostly of water and some salt. Even when the body does not appear to be noticeably sweating, approximately 500 mL of sweat is secreted a day. If the body becomes excessively warm due to high temperature, vigorous activity, or a combination of the two, sweat glands will be stimulated to produce large amounts of sweat. Sweat is released from the gland through a pore located at the skin’s surface. See Figure 5.8[8] for an illustration of an eccrine sweat gland.

Apocrine Sweat Glands

Apocrine sweat glands are found near hair follicles in densely hairy areas, such as the armpits and genital area. In addition to water and salt, apocrine sweat glands secrete organic compounds that make the sweat thicker and subject to bacterial decomposition, resulting in odor. The release of apocrine sweat is controlled by hormones and the nervous system. These glands aren’t active until puberty.

Sebaceous Glands

A sebaceous (oil) gland lubricates and waterproofs the skin and hair by producing and secreting an oily mixture called sebum. Most sebaceous glands are found next to hair follicles. Sebum performs the following actions:

- Provides natural lubrication

- Waterproofs the skin

- Prevents bacterial growth on the surface of the skin

- Helps prevent water loss from the body

Sebaceous glands are relatively inactive during childhood because the secretion of sebum is stimulated by hormones, many of which do not become active until puberty. Likewise, sebaceous gland activity decreases as we age due to decreased hormonal stimulation, leading to drier skin.

Ceruminous Glands

Ceruminous (wax) glands are found in the ear canal. These glands produce a waxy substance called cerumen that protects the ear canal from water and bacteria.

Sensory Receptors

Sensory receptors found throughout the skin help us interpret our environment and react accordingly. Receptors found in the skin include the following:

- Meissner corpuscle: The Meissner corpuscle (also referred to as a tactile corpuscle) detects light touch, such as an ant crawling across the skin or an eyelash on the cheek. See Figure 5.9[9] for an image of a Meissner corpuscle.

- Pacinian corpuscle: The Pacinian corpuscle (also referred to as a lamellated corpuscle) detects pressure and vibration.

- Merkel cell: Merkel cells are another type of touch receptor found scattered throughout stratum basale.

- Nociceptors: Nociceptors are found throughout the skin and detect pain.

- Thermoreceptors: Thermoreceptors are a special type of receptor that detect temperature.

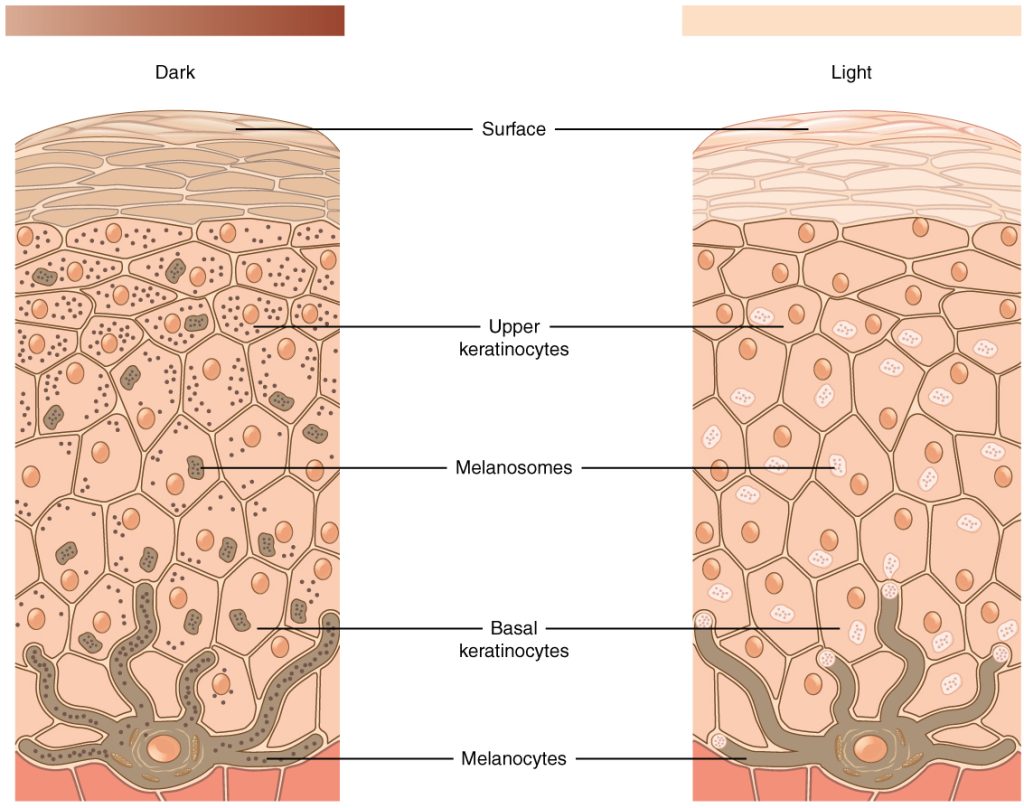

Skin Pigmentation

The color of skin is influenced by a number of pigments, including hemoglobin and melanin. Hemoglobin can give skin a reddish hue (or “rosy” color) to light-skinned individuals.

Melanin is a brownish/black pigment that is produced by cells called melanocytes, which are found in the stratum basale layer of the epidermis. Dark-skinned individuals produce more melanin than those with pale skin, although the number of melanocytes is relatively the same between different people. The genes you inherit from your parents determine your skin color. Exposure to the UV rays of the sun or a tanning bed causes more melanin to be produced and built up in keratinocytes, resulting in the darkening of the skin, or a tan. This increased melanin protects the DNA of skin cells from UV damage and the breakdown of folic acid, a nutrient necessary for our health. Too much melanin can interfere with the production of vitamin D, an important nutrient necessary for calcium absorption. Melanin production peaks about ten days after UV exposure, which is why pale-skinned individuals tend to sunburn more easily than dark-skinned individuals, who have more protection. See Figure 5.10[10] for an illustration of melanocytes that produce melanin.

Skin Color as a Diagnostic Tool

The color of the skin can provide helpful diagnostic clues, so examination of the skin should be part of any thorough physical examination. Common skin color changes include the following:

- Erythema: Redness of the skin. Increased blood flow to the surface of the skin can give skin a red appearance, such as from a burn or injury.

- Cyanosis: Bluish color of the skin. With a prolonged decrease in oxygen level, the skin can appear blue, a condition referred to as cyanosis (kyanos is the Greek word for “blue”). This happens when the oxygen supply is restricted, as when someone is experiencing difficulty breathing because of asthma or a heart attack.

- Jaundice: Yellowish appearance of the skin. Liver disease or liver cancer can cause the accumulation of bile and the yellow pigment bilirubin, leading to the skin appearing yellow or jaundiced (jaune is the French word for “yellow”). Infants born prematurely often develop jaundice due to their immature livers, which have trouble breaking down bilirubin.

- Pallor: Whitish color of the skin. A sudden drop in oxygen can affect skin color, causing the skin to initially turn ashen (white).

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2022). Anatomy and physiology 2e. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Skin_layers” by Madhero88 and M. Komorniczak is licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 ↵

- “Epidermis-delimited” by Fama Clamosa and Mikael Häggström, respectively is in the Public Domain ↵

- “502_Layers_of_epidermis” by OpenStax College: J. Gordon Betts, Peter Desaix, Eddie Johnson is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “502ab_Thin_Skin_versus_Thick_Skin” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “506_Layers_of_the_Dermis” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “507_Nails” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “508_Eccrine_gland” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “514_Light_Micrograph_of_a_Meissner_Corpuscle” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “504_Melanocytes” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Amoeba Sisters. (2022, December 21). Integumentary system [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=t1iQHHJ0YyE ↵

- Liang, B. (n.d.). Skin and the integumentary system [Video]. Wisc-Online. All rights reserved. https://www.wisc-online.com/learn/natural-science/life-science/ap12204/skin-and-the-integumentary-system ↵

- Forciea, B. (2022, December 24). Short topic video: The integument [Video]. YouTube. Used with permission. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2c7cW7O6Yo0 ↵

The outermost layer of the skin, providing a protective barrier.

Lacking blood vessels.

The primary cell type in the epidermis that produces keratin.

A structural protein found in skin, hair, and nails.

The outermost layer of the epidermis, composed of dead, keratinized cells.

The process by which keratinocytes harden to form the stratum corneum.

A thin, translucent layer of the epidermis found only in thick skin.

Clear, allowing light to pass through but not detailed images, as seen in the stratum lucidum.

A layer of the epidermis where keratinocytes begin to die and accumulate keratohyalin granules.

A layer of the epidermis that provides structural integrity and contains Langerhans cells.

Immune cells in the epidermis that help fight infection.

The deepest layer of the epidermis, where new skin cells are produced, also called the stratum germinativum.

A type of cell in the stratum basale that continuously divides to form new skin cells.

Sensory cells in the stratum basale that detect touch.

Cells in the epidermis that produce melanin.

The pigment responsible for skin, hair, and eye color.

Skin that covers most of the body and has fewer epidermal layers.

Skin found on the palms and soles, with extra layers for protection.

The thick layer of skin beneath the epidermis, containing nerves, blood vessels, and connective tissue.

The upper layer of the dermis with loose connective tissue and dermal papillae.

Finger-like projections in the dermis that increase surface area for nutrient exchange with the epidermis.

Fat cells that store energy in the form of lipids.

Sensory receptors in the skin that detect light touch.

The deeper layer of the dermis, composed of dense connective tissue.

Arranged in a net-like pattern, as seen in the collagen fibers of the reticular layer.

Protein fibers in the dermis that provide skin elasticity.

Strong, fibrous proteins that provide structural support in connective tissues.

The layer beneath the dermis that contains fat and connective tissue.

Another name for the hypodermis.

The connective tissue layer that separates skin from underlying muscles and bones.

A fibrous tissue that encloses muscles and organs.

A type of tissue that stores fat for energy and insulation.

The structure in the skin that produces hair.

The visible part of the hair above the skin surface.

The part of the hair embedded in the follicle.

A small muscle attached to hair follicles that causes hair to stand upright when contracted.

The area of skin beneath the nail that supplies nutrients and support.

The crescent-shaped, whitish area at the base of the nail caused by thick epithelium over the nail matrix, also called the "little moon."

The hard, visible part of the nail.

The white part of the nail that extends beyond the nail bed and helps fingers pick up small objects.

The part of the nail beneath the skin where new nail growth occurs.

The thin layer of skin at the base of the nail.

Another term for the cuticle, protecting the nail matrix.

The skin under the free edge of the nail that provides a seal against infections.

A gland that produces sweat for temperature regulation.

A sweat gland found in the armpits and groin, producing a thicker secretion.

A gland that secretes sebum to lubricate and protect the skin.

An oily substance produced by sebaceous glands to keep skin moisturized.

Glands in the ear that produce earwax.

Waxy substance.

A sensory receptor that detects light touch.

A sensory receptor that detects deep pressure and vibration.

A specialized skin cell that detects touch.

Pain receptors in the skin.

Sensory receptors that detect temperature changes.

A protein in red blood cells that carries oxygen and contributes to skin color.

Redness of the skin due to increased blood flow.

A bluish discoloration of the skin caused by poor oxygenation.

Yellowing of the skin and eyes due to excess bilirubin.

Unusual paleness of the skin due to reduced blood flow.