16.5 The Female Reproductive System

The Female Reproductive System[1]

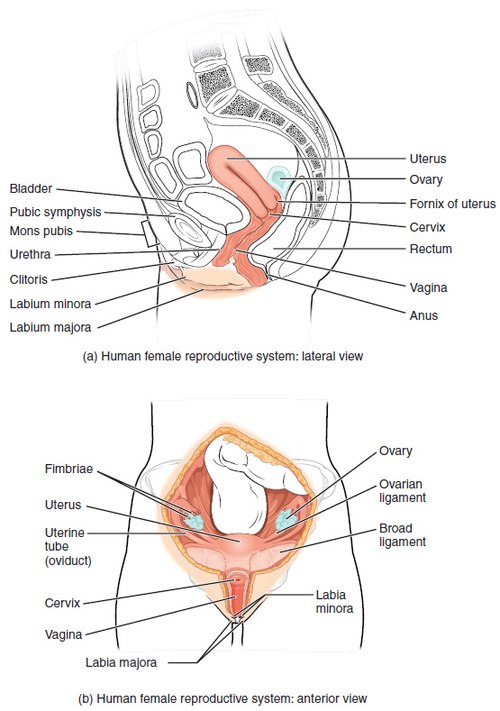

The female reproductive system produces reproductive hormones and ova (singular = ovum), also known as oocytes or eggs. It also supports and nourishes a developing fetus and delivers it to the outside world. The female reproductive system is located primarily inside the pelvic cavity.

The female reproductive system comprises internal and external structures. Key internal structures include the ovaries, Fallopian tubes, uterus, and cervix. The vulva (external genitalia) includes the mons pubis, labia majora, labia minora, clitoris, and vaginal opening.

See Figure 16.9[2] for an illustration of the female reproductive system.

Ovaries

The female gonads are the ovaries, a pair of small glands about the size of an almond. The ovaries are located within the pelvic cavity and are anchored to the uterus by the ovarian ligaments. The cortex makes up most of the adult ovary, and oocytes and follicles develop within this outer layer. Deep to the cortex is the inner ovarian medulla, which contains blood vessels, lymph vessels, and nerves. Refer back to Figure 16.9 for an illustration of the ovaries.

A follicle contains one oocyte and its supporting cells. The ovaries contain numerous follicles in different stages of development. Follicles grow and develop in a process called folliculogenesis, which typically leads to ovulation of one follicle approximately every 28 days. In addition, follicles produce estrogens and progesterone, which help to prepare the endometrium for a possible pregnancy. See the “Folliculogenesis” subsection in the “Female Puberty, Ovarian Cycle, and Menstrual Cycle” section for more information.

Fallopian Tubes

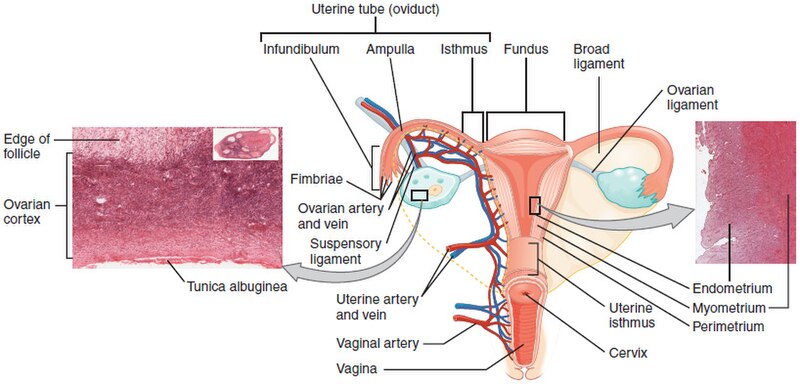

The Fallopian tubes (also called uterine tubes or oviducts) carry the ovulated oocyte to the uterus. Each of the two Fallopian tubes is close to, but not directly connected to, the ovary. The Fallopian tubes are divided into sections. The wide distal infundibulum flares out with slender, finger-like projections called fimbriae that sweep the egg into the Fallopian tube. The middle region of the Fallopian tube is called the ampulla and is where fertilization often occurs. The isthmus is the narrow medial end of the Fallopian tube that is connected to the uterus.

The Fallopian tubes also have three layers: an outer serosa, a middle smooth muscle layer, and an inner mucosal layer. In addition to its mucus-secreting cells, the inner mucosa contains ciliated cells that beat towards the direction of the uterus to move the oocyte to it. The Fallopian tubes also use peristalsis to move the oocyte towards the uterus. See Figure 16.10[3] for an illustration of the Fallopian tubes.

Uterus

The uterus is a muscular organ that nourishes and supports a growing embryo and fetus. The lay term for this organ is the womb. Its average size is approximately 5 cm wide by 7 cm long (approximately 2 inches by 3 inches) when the individual is not pregnant and can grow to up to 500 times its size during the full term of a pregnancy. The uterus has three sections. The portion of the uterus superior to the opening of the uterine tubes is called the fundus. The middle section of the uterus is called the body (or corpus). The cervix is the narrow inferior portion of the uterus that projects into the vagina.

Several ligaments maintain the position of the uterus within the pelvic cavity. The broad ligament serves as a primary support for the uterus, extending laterally from both sides of the uterus and attaching it to the pelvic wall. The round ligament attaches to the uterus near the Fallopian tubes and extends to the labia majora. The uterosacral ligament stabilizes the uterus posteriorly by its connection from the cervix to the pelvic wall.

The wall of the uterus is made up of three layers: the perimetrium, the myometrium, and the endometrium. The most superficial layer is the perimetrium, a serous membrane that covers the outside of the uterus. The myometrium is the middle smooth muscular layer that makes up most of the uterus and is responsible for uterine contractions. The muscle fibers run horizontally, vertically, and diagonally to create the powerful contractions that occur during labor and the less powerful contractions (or cramps) that occur during a menstrual period.

The innermost layer of the uterus is called the endometrium. The endometrium has a rich blood supply and consists of two sublayers: the stratum basalis and the stratum functionalis. The stratum basalis (or basal layer) is the deeper layer that creates the more superficial stratum functionalis. The stratum functionalis (or functional layer) grows and thickens in response to increased levels of estrogen and progesterone in preparation for a potential pregnancy. If fertilization does not occur, the stratum functionalis is shed during menstruation.

Cervix

The cervix is the narrow inferior portion of the uterus that projects into the vagina. The opening at the inferior end of the cervix is called the external os. The cervix produces mucus that changes in consistency throughout the menstrual cycle. Normally, the mucus is thick to prevent sperm from entering the uterus. However, during ovulation, the mucus will become thin and stretchy to allow sperm to move through the reproductive tract.

Refer back to Figure 16.9 for an illustration of the uterus and cervix.

Vagina

The vagina is the female copulatory (sex) organ. It is a muscular canal approximately 4 inches (10 cm) long that serves as the entrance to the reproductive tract. It also serves as the exit from the uterus for menstruation and childbirth. The walls of the vagina are able to expand to accommodate intercourse and childbirth.

The hymen is a thin membrane that sometimes partially covers the entrance to the vagina. An intact hymen is not an indication of virginity. Even at birth, this is only a partial membrane, as menstrual fluid and other secretions must be able to exit the body, regardless of penile–vaginal intercourse. The hymen can be ruptured with strenuous physical exercise, inserting things into the vagina, and childbirth.

The vagina has a normal population of microorganisms that protect against infection by harmful organisms that can enter the vagina. In a healthy person, the most predominant type of vaginal bacteria is from the genus Lactobacillus. This family of beneficial bacterial flora secretes lactic acid and, thus, protects the vagina by maintaining an acidic pH (less than 4.5). Potential pathogens are less likely to survive in these acidic conditions. Lactic acid, in combination with other vaginal secretions, makes the vagina a self-cleansing organ.

Douching—or washing out the vagina with fluid—can disrupt the normal balance of healthy microorganisms and actually increase risk for infections and irritation. The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists recommends that people not douche and that they allow the vagina to maintain its normal healthy population of protective microbial flora.

Refer back to Figure 16.9 for an illustration of the vagina.

External Female Anatomy

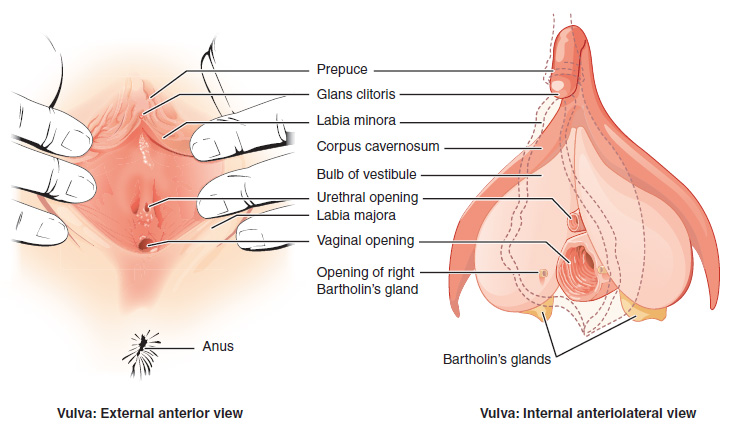

The external female reproductive structures are referred to collectively as the vulva. The vulva includes the mons pubis, labia majora and minora, clitoris, and vestibule.

The mons pubis is a pad of fat that is located superficial to the pubic bone. After puberty, it becomes covered in pubic hair. The labia majora (labia = “lips”; majora = “larger”) are folds of hair-covered skin that begin just posterior to the mons pubis. The thinner and more pigmented labia minora (labia = “lips”; minora = “smaller”) are medial to the labia majora and do not have hair. Although they naturally vary in shape and size from person to person, the labia minora serve to protect the urethra and the vaginal orifice.

The superior, anterior portions of the labia minora come together to encircle the clitoris (or glans clitoris), an organ that originates from the same cells as the glans penis. The clitoris has abundant nerves that make it important in sexual sensation and orgasm. The vestibule is the area between the labia minora where the external urethral orifice and vaginal orifice are located. The two Bartholin’s (or greater vestibular) glands are located lateral to the vaginal orifice. They produce mucus that adds lubrication to the vagina.

See Figure 16.11[4] for an illustration of the vulva.

Perineum

In both females and males, the area between the genitals and the anus is called the perineum. The muscles in the perineum are important for urination in both sexes, ejaculation in males, and vaginal contraction in females. The pelvic floor muscles support the pelvic organs; resist intraabdominal pressure; and work as sphincters for the urethra, rectum, and vagina.

Vaginal birth causes significant stretching of the vaginal canal, cervix, and perineum and can cause the perineum to tear. An obstetrician may elect to numb the perineum during childbirth and perform an episiotomy, an incision made in the posterior vaginal wall and perineum to prevent tearing and to also facilitate the birth of the fetus’ head. Perineal tears and episiotomies must be sutured shortly after birth to ensure optimal healing.

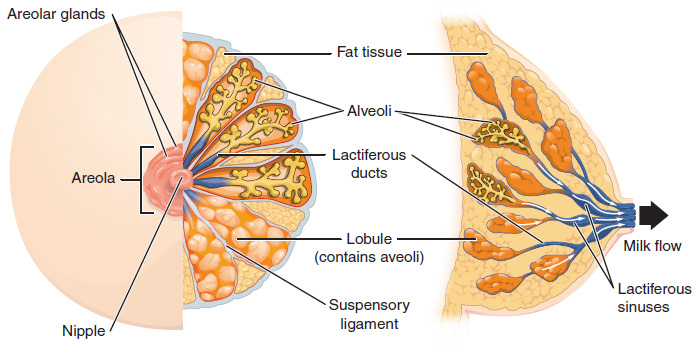

Breasts and Mammary Glands

The breasts are considered accessory organs of the female reproductive system. They are located anterior to the pectoralis major muscles of the chest. The breast includes a nipple surrounded by a pigmented areola. The areola is typically circular in shape and can vary in size from 1 to 4 inches (25 to 100 mm) in diameter, which may become darker in color during pregnancy. The areolar region is characterized by small, raised areolar glands that secrete lubricating fluid during lactation to protect the nipple from chafing.

The breasts contain adipose tissue, which determines the size of the breast. Breast size differs between individuals and does not affect the amount of milk that can be produced. Supporting the breasts are multiple bands of connective tissue called suspensory ligaments that connect the breast tissue to the dermis of the overlying skin.

During the normal hormonal fluctuations in the menstrual cycle, breast tissue responds to changing levels of estrogen and progesterone, which can lead to swelling and breast tenderness in some individuals. If pregnancy occurs, the increase in hormones leads to further development of the mammary tissue and enlargement of the breasts.

See Figure 16.12[5] for an illustration of the anatomy of the breast.

The function of the breasts is to produce and supply milk to an infant in a process called lactation. Breast milk is produced by the mammary glands, which are modified sweat glands. The hormone prolactin (PRL) promotes lactation. During pregnancy, it contributes to development of the mammary glands, and after birth, it stimulates the mammary glands to produce breast milk. The effects of prolactin rely on the permissive effects of estrogens, progesterone, and other hormones. In non-pregnant individuals, prolactin secretion is inhibited by prolactin-inhibiting hormone (PIH). Only during pregnancy do prolactin levels rise in response to prolactin-releasing hormone (PRH) from the hypothalamus.

When a baby nurses, the entire areolar region is taken into the mouth. Milk leaves the breast through the nipple via 15 to 20 lactiferous ducts that open to the surface of the nipple. The baby withdraws milk from the breast by suckling. The hormone oxytocin is necessary for the milk ejection reflex (commonly referred to as “letdown”) for the baby to get milk. As the baby begins suckling, sensory receptors in the nipples transmit signals to the hypothalamus. In response, oxytocin is secreted and released into the bloodstream. Within seconds, cells in the milk ducts contract, ejecting milk into the infant’s mouth.

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2022). Anatomy and physiology 2e. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Figure_28_02_01.JPG” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “Figure_28_02_06” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “Vulva_Figure_28_02_02” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “Figure_28_02_09.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

A pair of small glands, about the size of an almond, that serve as the female gonads.

Fibrous bands that connect each ovary to the uterus, helping to hold the ovary in place.

A structure that contains one oocyte and its supporting cells.

Also called uterine tubes or oviducts; carry the ovulated oocyte to the uterus.

The funnel-shaped opening near the ovary that captures and directs the released oocyte into the fallopian tube.

Slender, finger-like projections that sweep the egg into the fallopian tube.

The middle region of the Fallopian tube.

The narrow medial end of the Fallopian tube that is connected to the uterus.

A muscular organ (also called the womb) that nourishes and supports a growing embryo and fetus, expanding up to 500 times its normal size during pregnancy.

The dome-shaped upper part of the stomach, positioned below the diaphragm and above and to the left of the cardia.

The middle section of the uterus.

The narrow inferior portion of the uterus that projects into the vagina.

A primary support for the uterus, extending laterally from both sides of the uterus and attaching it to the pelvic wall.

Attaches to the uterus near the Fallopian tubes and extends to the labia majora.

Stabilizes the uterus posteriorly by its connection from the cervix to the pelvic wall.

A serous membrane that covers the outside of the uterus.

The middle smooth muscular layer that makes up most of the uterus and is responsible for uterine contractions.

Innermost layer of the uterus.

The deeper layer of the endometrium that creates and regenerates the more superficial stratum functionalis layer.

Grows and thickens in response to increased levels of estrogen and progesterone in preparation for a potential pregnancy.

The female copulatory (sex) organ.

A thin membrane that sometimes partially covers the entrance to the vagina.

The external female reproductive structures.

A pad of fat that is located superficial to the pubic bone.

Folds of hair-covered skin that begin just posterior to the mons pubis.

The smaller, hairless inner folds of skin situated medial to the labia majora.

A highly innervated organ derived from the same embryonic tissue as the glans penis, important for sexual sensation and orgasm.

Chamber of the inner ear responsible for balance and spatial orientation.

Glands that produce mucus which adds lubrication to the vagina.

The area between the genitals and the anus.

An incision made in the posterior vaginal wall and perineum to prevent tearing and to also facilitate the birth of the fetus’ head.

Considered accessory organs of the female reproductive system.

The circular pigmented area around the nipple containing glands that secrete lubricating fluid during lactation to protect against chafing.

Connect the breast tissue to the dermis of the overlying skin.

The process by which the breasts produce and supply milk to nourish an infant.

Modified sweat glands that produce breast milk.

Promotes lactation (milk production).

A hormone that stimulates uterine contractions and cervix dilation to help with childbirth.