16.3 Male Reproductive System Anatomy

Male Reproductive System Anatomy[1]

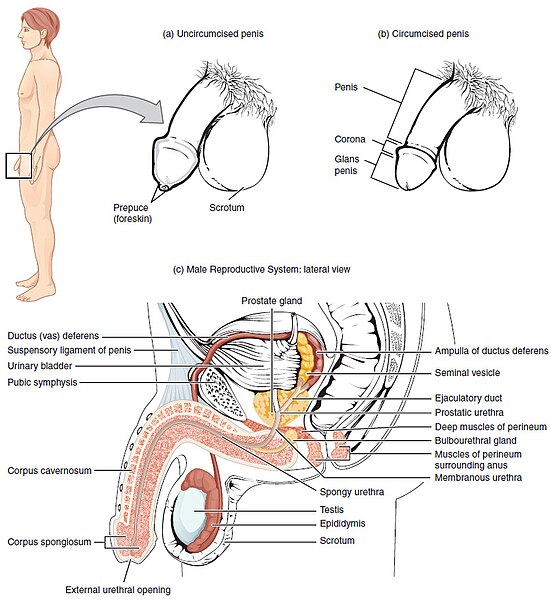

The structures of the male reproductive system include the scrotum, testes, epididymis, vas deferens, accessory glands, penis, and urethra. See Figure 16.1[2] for an illustration of the structures of the male reproductive system.

Scrotum

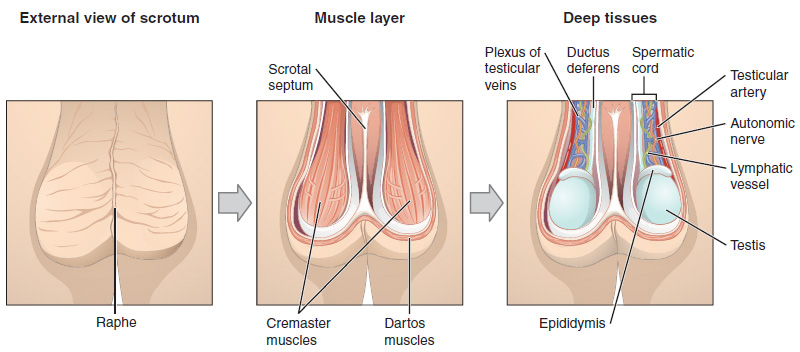

The scrotum is a muscular sac that contains the testes (singular = testis). It hangs slightly away from the body posterior to the penis. This location is important as viable sperm production in the testes requires a temperature 2 to 4°C below core body temperature.

The dartos muscle makes up the muscle layer of the scrotum. It continues internally to make up the scrotal septum, a wall that divides the scrotum into two compartments, each housing one testis.

Two cremaster muscles cover each testis like a muscular netting. By contracting simultaneously, the dartos and cremaster muscles can elevate the testes when cold, moving the testes closer to the body and decreasing the surface area of the scrotum to retain heat. Alternatively, as temperature increases, the scrotum relaxes, moving the testes farther from the body and increasing scrotal surface area, which promotes heat loss. Externally, the scrotum has a raised medial thickening on the surface called the raphae.

See Figure 16.2[3] for an illustration of the scrotum.

Testes

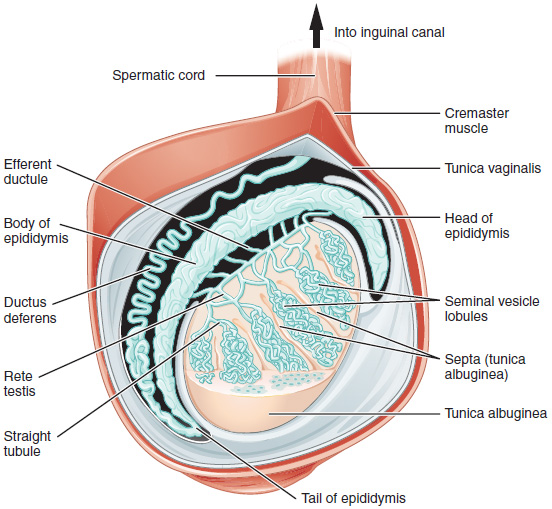

The testes (singular = testis) are the male reproductive organs or gonads. They produce both sperm and hormones such as testosterone and are active from puberty until death. The two adult testes are each approximately 4 to 5 cm in length and are housed within the scrotum.

Very long and tightly coiled seminiferous tubules form the interior of each testis. The seminiferous tubules are composed of Sertoli cells that contain developing sperm. These immature sperm are released into the lumen or hollow center of the seminiferous tubules and make their way to the epididymis.

See Figure 16.3[4] for an illustration of the anatomy of the testes.

Cells of the Testes

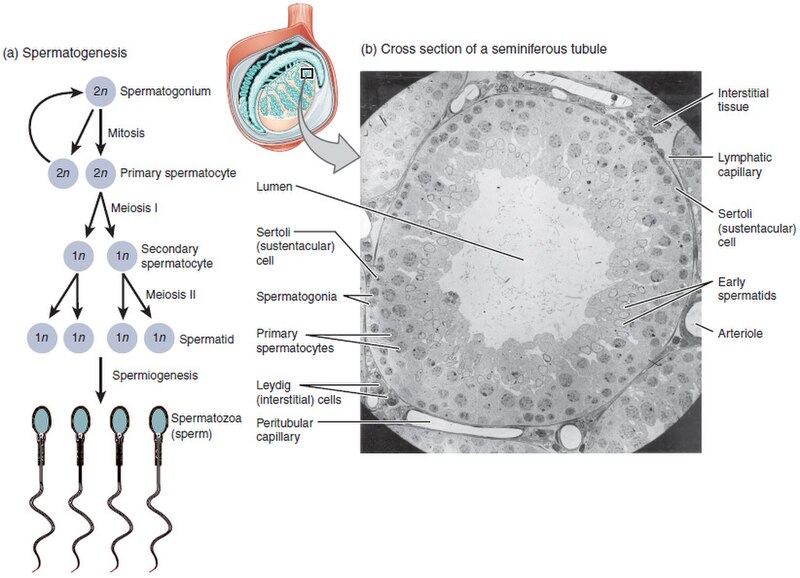

There are many different cells found within the testes, including spermatogonia, sperm cells, Sertoli cells, and Leydig cells.

Spermatogonia and Sperm

The least mature cells in the testes are the spermatogonia (singular = spermatogonium). Spermatogonia are the stem cells of the testis, which means that they are able to differentiate into sperm.

Spermatogonia divides via mitosis into two cells. One is retained as a spermatogonium, and the other cell differentiates into a primary spermatocyte. The primary spermatocyte undergoes meiosis I to form two haploid secondary spermatocytes. These two cells undergo Meiosis II to form four spermatids, which then develop into mature sperm. The process that begins with spermatogonia and ends with mature sperm is called spermatogenesis. See Figure 16.4[5] for an illustration of spermatogenesis.

View a supplementary YouTube video[6] on spermatogenesis: Spermatogenesis.

Sertoli Cells

Surrounding the developing sperm cells are Sertoli cells. Sertoli cells (or sustentacular cells) are a type of supporting cells that are typically found in epithelial tissue. Sertoli cells promote sperm production and can control whether sperm live or die. Tight junctions between these sustentacular cells create the blood–testis barrier, which protects developing sperm from the individual’s immune system. Refer back to Figure 16.4 for an illustration of Sertoli cells.

Leydig Cells

A fourth type of cell found in the testes is the Leydig cell, which produces the hormone testosterone. The alternate term for Leydig cells is interstitial cells, which reflects their location between the seminiferous tubules in the testes. Refer back to Figure 16.4 for an illustration of Leydig cells.

Epididymis

From the lumen of the seminiferous tubules, the sperm are surrounded by testicular fluid and moved to the epididymis (plural = epididymides), a coiled tube attached to the testis where newly formed sperm continue to mature.

Though the epididymis does not take up much room due to its tightly coiled shape, it would be approximately 6 m (20 feet) long if straightened. It takes an average of 12 days for sperm to move through the coils of the epididymis. As sperm move through the epididymis, the sperm further mature and acquire the ability to move on their own. The more mature sperm are then stored in the tail of the epididymis (the final section) until ejaculation occurs. Refer back to Figure 16.3 illustrating the anatomy of a testis to view the epididymis.

Vas (Ductus) Deferens

During ejaculation, sperm exit the tail of the epididymis and are pushed by smooth muscle contraction through the vas deferens (also called the ductus deferens). The vas deferens are two thick, muscular tubes that are bundled together inside the scrotum with connective tissue, blood vessels, lymphatic vessels, muscle, and nerves into a structure called the spermatic cord. Refer back to Figures 16.1 and 16.2 to view an illustration of the vas (ductus) deferens.

From each epididymis, each vas deferens extends superiorly into the abdominal cavity through the inguinal canal in the abdominal wall. From here, the vas deferens continues into the pelvic cavity, ending posterior to the bladder where it dilates in a region called the ampulla (meaning “flask”).

Because the vas deferens is physically accessible within the scrotum, surgical sterilization to prevent sperm delivery can be performed by cutting and sealing a small section of the vas deferens. This procedure is called a vasectomy, and it is an effective form of birth control. Although it may be possible to reverse a vasectomy, clinicians consider the procedure permanent.

View this supplementary Medline Plus video[7] to learn more about a vasectomy: Vasectomy.

Accessory Glands

Sperm make up only 5 percent of semen, the thick, milky fluid that is ejaculated. The normal volume of semen varies from 1.5 to 5.0 milliliter per ejaculation with sperm count varying from 20 to 150 million sperm per milliliter.[8]

Most of semen is produced by the accessory glands of the male reproductive system: the seminal vesicles, the prostate gland, and the bulbourethral glands. Semen has an alkaline pH. This is important to help neutralize the acidity of the vagina so that some sperm survive.

Seminal Vesicles

As sperm pass through the ampulla of each vas deferens at ejaculation, they mix with fluid from the seminal vesicle (or seminal gland). The paired seminal vesicles are glands that contribute approximately 60 percent of the semen volume. Seminal vesicle fluid contains prostaglandins to help with sperm motility and large amounts of fructose, which is used by the sperm mitochondria as an energy source to generate ATP to produce movement through the female reproductive tract.

The fluid, now containing both sperm and seminal vesicle secretions, moves into the ejaculatory duct, a short structure formed from the ampulla of the vas deferens and the duct of the seminal vesicle. The paired ejaculatory ducts transport the seminal fluid into the prostate gland.

Refer back to Figure 16.1 for an illustration of the seminal vesicles and the ejaculatory duct.

Prostate Gland

The prostate gland sits inferior to the bladder surrounding the prostatic urethra (the portion of the urethra that travels through the prostate). About the size of a walnut, the prostate gland is formed of both muscular and glandular tissues. It adds an alkaline, milky fluid to the semen that is important to first coagulate (thicken) and then de-coagulate the semen following ejaculation. The temporary thickening of semen helps retain it within the female reproductive tract, providing time for sperm to utilize the fructose provided by seminal vesicle secretions. The semen then liquifies so sperm can pass farther into the female reproductive tract. Refer back to Figure 16.1 for an illustration of the prostate gland. The prostate gland also adds citric acid, an important nutrient and seminalplasmin, a natural antibiotic, to the semen.[9]

Prostate specific antigen (PSA) is a protein produced by both cancerous and noncancerous tissue in the prostate. Prostate specific antigen is mostly found in semen but small amounts of PSA also circulate in the blood. The PSA test is a blood test used primarily to screen for prostate cancer. The test measures the amount of prostate-specific antigen in the blood and can detect high levels of PSA that may indicate the presence of prostate cancer. However, many other conditions, such as an enlarged or inflamed prostate, also can increase PSA levels.[10]

Bulbourethral Glands

The final addition to semen is made by two bulbourethral glands (also known as Cowper’s glands). The bulbourethral glands release a thick, salty fluid that lubricates the end of the urethra and the vagina and helps to clean urine residues from the penile urethra. The fluid from these accessory glands is released after the male becomes sexually aroused and shortly before the release of the semen. It is sometimes called pre-ejaculate. Refer back to Figure 16.1 for an illustration of the bulbourethral glands.

View this MedLine Plus video[11] to explore the structures of the male reproductive system and the path of sperm that begins in the testes and ends as they leave the penis through the urethra: Sperm Release Pathway.

Penis

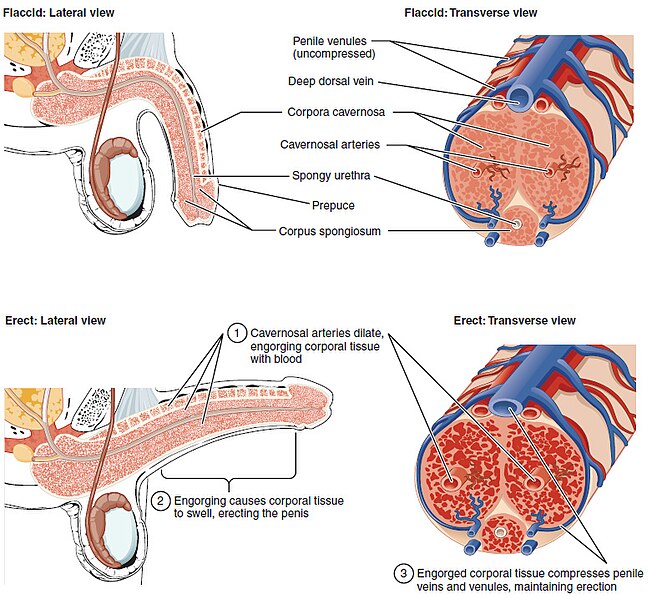

The penis is the male copulatory (sex) organ. It is soft for non-sexual actions such as urination and swollen and rod-like with sexual arousal. Three columns of erectile tissue make up most of the volume of the penis. When erect, the stiffness of the penis allows it to penetrate into a female’s vagina and deposit semen into the reproductive tract.

Shaft of Penis

The shaft of the penis is composed of three column-like chambers of erectile tissue. Each of the two larger lateral chambers is called a corpus cavernosum (plural = corpora cavernosa). Together, these make up the bulk of the penis. The corpus spongiosum, which can be felt as a raised ridge on the erect penis, is a smaller chamber that surrounds the spongy, or penile, urethra and makes up the head (or glans) of the penis.

See Figure 16.5[12] for illustrations of a flaccid and erect penis.

Glans Penis

The end of the penis, called the glans penis, has a high concentration of nerve endings, resulting in very sensitive skin. The skin from the shaft extends down over the glans and forms a covering called the prepuce (also known as the foreskin). The prepuce also contains a dense concentration of nerve endings and both lubricates and protects the sensitive skin of the glans penis. A surgical procedure called circumcision, often performed for religious or social reasons, removes the prepuce, typically within days of birth.

Both sexual arousal and REM sleep (during which dreaming occurs) can cause an erection. Erections are the result of vasocongestion, or engorgement of the tissues because more arterial blood is flowing into the penis than is leaving. Depending on the flaccid dimensions of a penis, it can increase in size slightly or greatly during erection, with the average length of an erect penis measuring approximately 6 inches (15 cm).

Urethra

The penis contains the urethra that carries both urine and semen out of the body. The urethra has three regions, including the prostatic urethra, the membranous urethra, and the spongy (or penile) urethra.

The prostatic urethra passes through the prostate gland. During sexual intercourse, it receives sperm via the ejaculatory ducts and secretions from the seminal vesicles. The bulbourethral glands produce and secrete mucus into the urethra to buffer urethral pH during sexual stimulation. The mucus neutralizes the usually acidic environment and lubricates the urethra, decreasing the resistance to ejaculation. The short membranous urethra passes through the deep muscles of the perineum between the prostate gland and the penis. The spongy (or penile) urethra is the longest section. It passes through the length of the penis and exits at the tip of the penis through an opening called the external urethral orifice. Refer back to Figure 16.1 for an illustration of the regions of the urethra.

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2022). Anatomy and physiology 2e. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “Figure_28_01_01.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “Figure_28_01_02” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “Figure_28_01_03.JPG” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “Figure_28_01_04” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Staffero, L. (2014, October 19). Spermatogenesis [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=X829u3LqCn0 ↵

- A.D.A.M. (2024, March 31). Vasectomy [Video]. Medline Plus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/anatomyvideos/000139.htm ↵

- Medline [Internet]. (2024). Semen analysis. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003627.htm ↵

- Shivaji S. (1988). Seminalplasmin: A protein with many biological properties. Bioscience Reports, 8(6), 609–618. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF01117340 ↵

- Mayo Clinic. (2025). PSA test. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/psa-test/about/pac-20384731 ↵

- A.D.A.M. (2024, March 31). Sperm release pathway [Video]. Medline Plus. https://medlineplus.gov/ency/anatomyvideos/000121.htm ↵

- “Figure_28_01_06” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

A muscular sac that contains the testes.

The muscle layer of the scrotum.

A wall that divides the scrotum into two compartments, each housing one testis.

Two muscles that cover each testis like a muscular netting.

A seam or ridge marking the line of fusion between two symmetrical structures in the body.

The male reproductive organs or gonads.

Long, coiled structures within the testes where sperm production occurs.

Stem cells located in the seminiferous tubules that divide to produce sperm cells.

The process that begins with spermatogonia and ends with mature sperm.

A type of supporting cells that are typically found in epithelial tissue.

Protects developing sperm from the individual’s immune system.

Produces the hormone testosterone.

Cells found between the seminiferous tubules in the testes that produce the hormone testosterone.

A coiled tube attached to the testis where newly formed sperm continue to mature.

A long, muscular tube that transports sperm from the epididymis to the ejaculatory duct in preparation for ejaculation.

A bundle of nerves, ducts, and blood vessels that supports the testicles and carries sperm to the urethra.

A passage in the lower anterior abdominal wall through which the spermatic cord passes in males (and the round ligament in females).

A surgical procedure for male sterilization in which the vas deferens is cut or sealed to prevent sperm from entering the semen.

The thick, milky fluid that is ejaculated.

A paired gland that secretes a thick, alkaline fluid rich in fructose and other substances that nourish and promote the motility of sperm.

A short structure formed from the ampulla of the vas deferens and the duct of the seminal vesicle.

A walnut-sized gland that surrounds the urethra and secretes a slightly acidic, milky fluid that helps nourish and transport sperm.

The portion of the urethra that travels through the prostate.

A protein produced by both cancerous and noncancerous tissue in the prostate.

A blood test used primarily to screen for prostate cancer.

Small glands that release a thick, salty fluid to lubricate the urethra and vagina and cleanse urine residues from the penile urethra.

Small glands that release a thick, salty fluid to lubricate the urethra and vagina and cleanse urine residues from the penile urethra.

The male copulatory (sex) organ.

One of two columns of erectile tissue in the penis that fill with blood to produce an erection.

The single column of erectile tissue surrounding the urethra in the penis that fills with blood during an erection to keep the urethra open.

The rounded, sensitive tip of the penis that is covered by the foreskin unless circumcised.

The fold of skin that covers and protects the glans penis.

The fold of skin that covers and protects the glans penis.

A surgical procedure that removes the prepuce (foreskin), often performed for religious or social reasons, typically within days of birth.

Engorgement of the tissues because more arterial blood is flowing into the penis than is leaving.

The short segment of the male urethra that passes through the pelvic floor muscles between the prostate and the penis.

The longest part of the male urethra that runs through the corpus spongiosum of the penis and ends at the external urethral orifice.

The external opening at the tip of the penis through which urine and semen exit the body.