12.3 Structure of the Lymphatic System

Structure of the Lymphatic System[1]

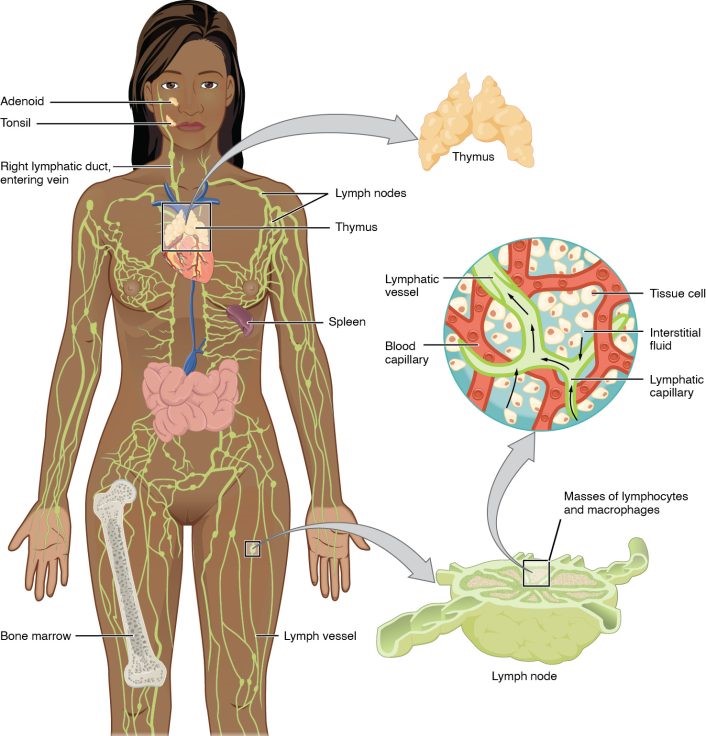

The lymphatic vessels begin as lymphatic capillaries, which feed into larger and larger lymphatic vessels, and eventually empty into the bloodstream by ducts. Along the way, the lymph travels through the lymph nodes, which are commonly found near the groin, armpits, neck, chest, and abdomen. See Figure 12.2[2] for an illustration of the lymphatic system.

A major distinction between the lymphatic and cardiovascular systems in humans is that lymph is not actively pumped by the heart but is forced through the vessels by the movements of the body, the contraction of skeletal muscles during body movements, and breathing. One-way valves in lymphatic vessels keep the lymph moving toward the heart. Lymph flows from the lymphatic capillaries, through lymphatic vessels, and then is dumped into the circulatory system via the lymphatic ducts located at the junction of the jugular and subclavian veins in the neck.

Lymphatic Capillaries

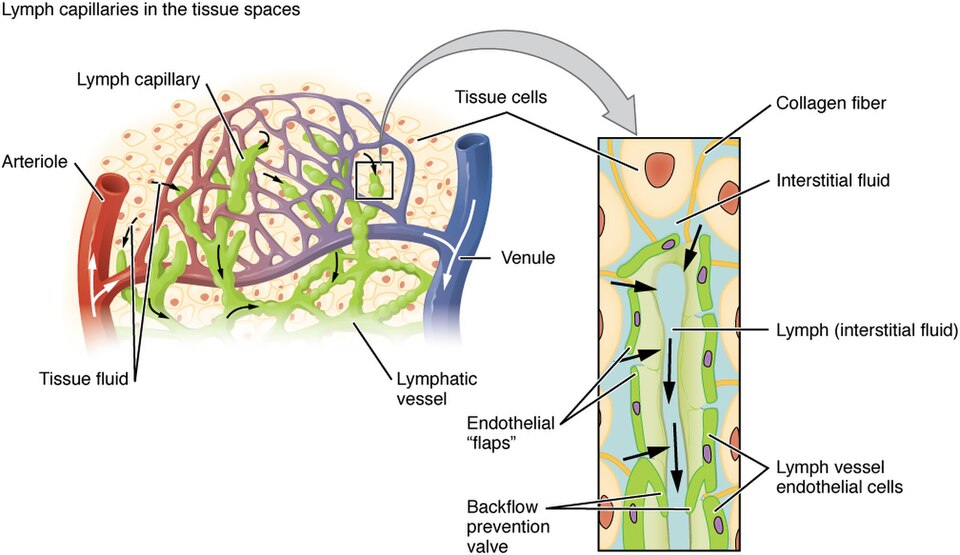

Lymphatic capillaries, also called the terminal lymphatics, are vessels where interstitial fluid enters the lymphatic system to become lymph fluid. Located in almost every tissue in the body, these vessels are woven among the arterioles and venules of the circulatory system in the soft connective tissues of the body. Exceptions are the central nervous system, bone marrow, bones, teeth, and the cornea of the eye, which do not contain lymph vessels. Lymphatic capillaries are formed by a one cell thick layer of endothelial cells and represent the open end of the system, allowing interstitial fluid to flow into them via overlapping cells. See Figure 12.3[3] for an illustration of lymphatic capillaries.

In the small intestine, lymphatic capillaries called lacteals are necessary for the transport of dietary lipids and lipid-soluble vitamins to the bloodstream. In the small intestine, dietary triglycerides combine with other lipids and proteins and enter the lacteals to form a milky fluid called chyle. The chyle then travels through the lymphatic system, eventually entering the bloodstream.

Larger Lymphatic Vessels, Trunks, and Ducts

The lymphatic capillaries empty into larger lymphatic vessels, which are similar to veins in terms of their three-tunic structure and the presence of valves. These one-way valves are located fairly close to one another, and each one causes a bulge in the lymphatic vessel, giving the vessels a beaded appearance.

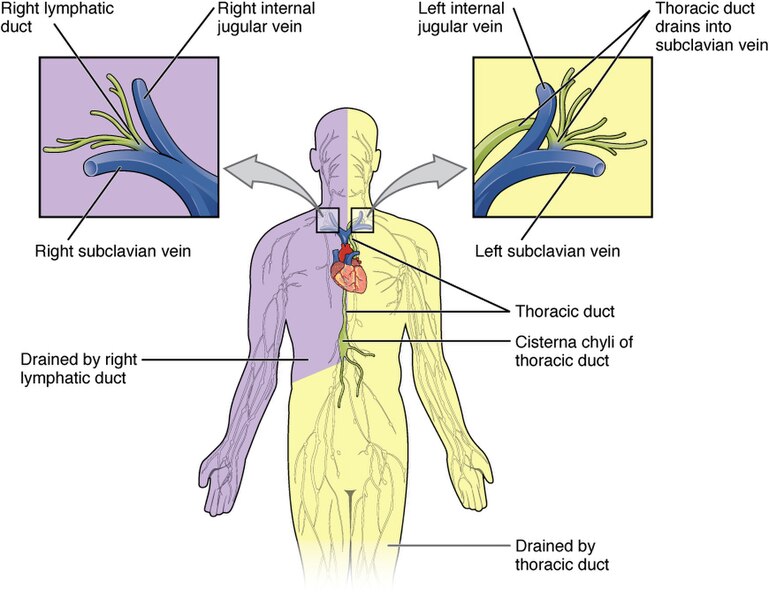

The superficial and deep lymphatics eventually merge to form larger lymphatic vessels known as lymphatic trunks. The overall drainage system of the body is asymmetrical. The right lymphatic duct receives lymph from only the upper right side of the body. The lymph from the rest of the body enters the bloodstream through the much larger thoracic duct via all the remaining lymphatic trunks.

In general, lymphatic vessels of the subcutaneous tissues of the skin, that is, the superficial lymphatics, follow the same routes as veins, whereas the deep lymphatic vessels of the viscera generally follow the paths of arteries. See Figure 12.4[4] for an illustration of lymphatic and thoracic ducts.

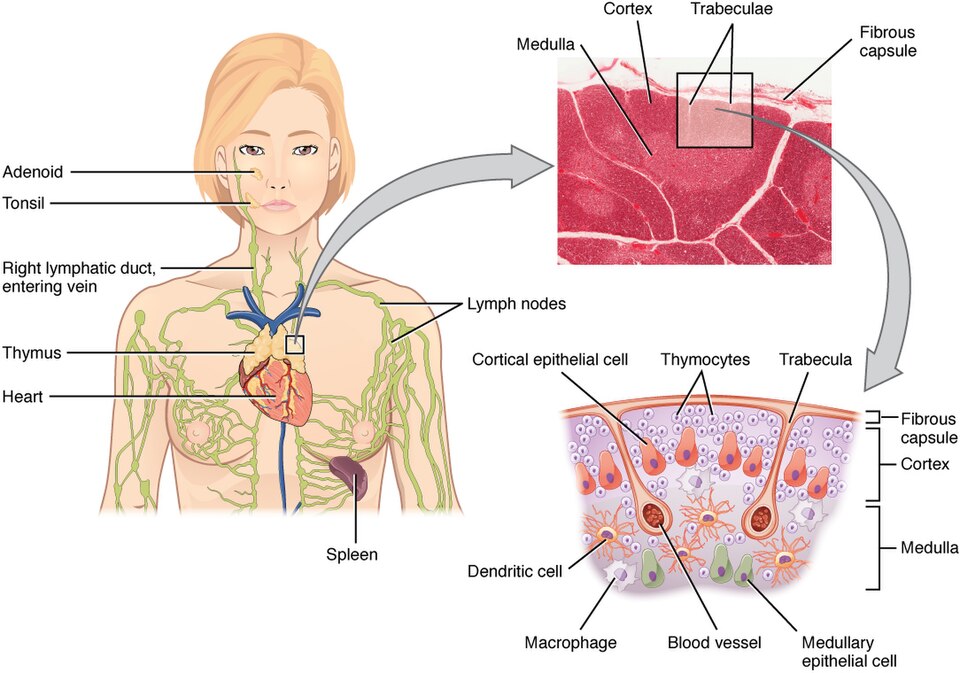

Thymus

The thymus gland is a bi-lobed organ found in the space between the sternum and the aorta of the heart. Connective tissue holds the lobes closely together but also separates them and forms a capsule. The thymus is involved in the development and maturation of T-cells and is particularly active during infancy and childhood and begins to shrink during puberty. See Figure 12.5[5] for an illustration of the thymus.

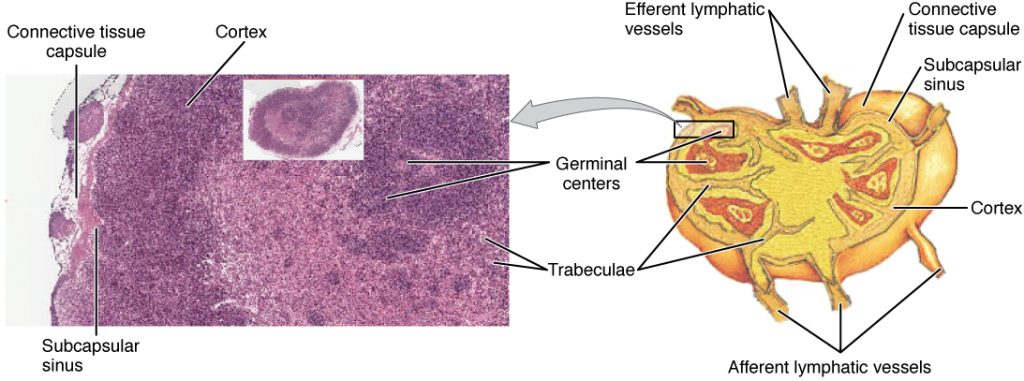

Lymph Nodes

Humans have about 500–600 lymph nodes throughout the body, with major locations being the groin, armpits, neck, chest, and abdomen. Lymph nodes function to remove debris and pathogens from the lymph and are, thus, sometimes referred to as the “filters of the lymph.” Any bacteria that infect the interstitial fluid are taken up by the lymphatic capillaries and transported to a regional lymph node. Dendritic cells (a special type of phagocyte) and macrophages within this organ internalize and kill many of the pathogens that pass through, thereby removing them from the body. The lymph node is also the site of specific immunity responses mediated by T cells, B cells, and accessory cells of the specific immune system. See Figure 12.6[6] for an illustration of a lymph node.

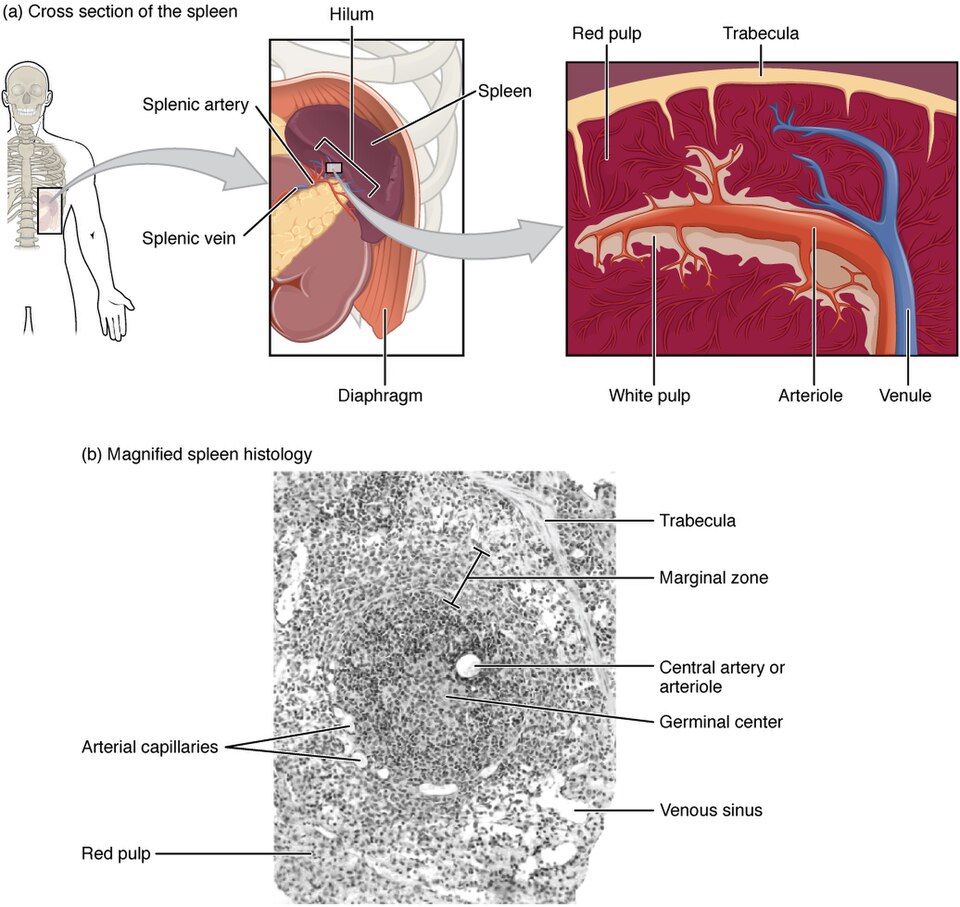

Spleen

In addition to the lymph nodes, the spleen is a major secondary lymphoid organ. It is about 12 cm (5 in) long. The spleen is a fragile organ without a strong capsule and is dark red due to its extensive vascularization. The spleen is sometimes called the “filter of the blood” because of the presence of macrophages and dendritic cells that remove microbes and other materials from the blood, including old red blood cells. The spleen also functions as the location of immune responses to blood-borne pathogens.

The spleen is made up of red pulp, consisting mostly of red blood cells and white pulp consisting of lymphatic tissue. Thus, the red pulp primarily functions as a filtration system of the blood, using cells of the relatively nonspecific immune system, and white pulp is where adaptive T and B cell responses are mounted. See Figure 12.7[7] for an illustration of the spleen.

Lymphoid Nodules

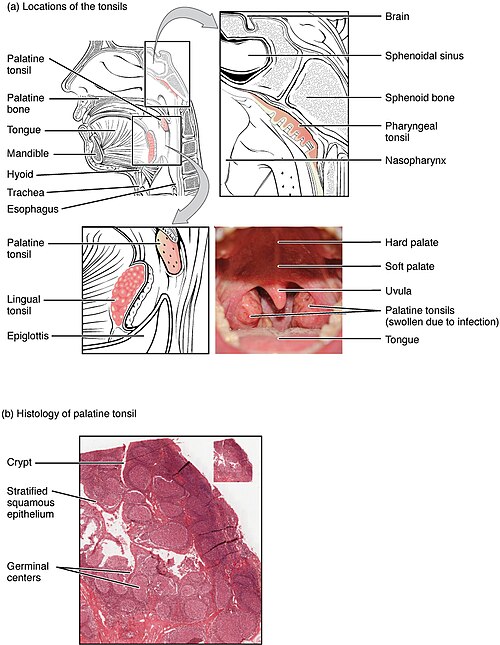

The other lymphoid tissues, the lymphoid nodules, are similar to the spleen and lymph nodes in that they consist of a dense cluster of lymphocytes without a surrounding fibrous capsule. These nodules are located in the respiratory and digestive tracts, areas routinely exposed to environmental pathogens.

Tonsils are lymphoid nodules located along the inner surface of the pharynx (throat) and are important in developing immunity to oral pathogens. The tonsils include the palatine tonsils located at the back of the throat; the pharyngeal tonsil, commonly referred to as the adenoid located in the throat behind the nose; and the lingual tonsils found at the base of the tongue. When tonsils are swollen, it is an indication of an active immune response to infection.

Histologically, tonsils do not contain a complete capsule, and the epithelial layer invaginates deeply into the interior of the tonsil to form tonsillar crypts. These structures, which accumulate all sorts of materials taken into the body through eating and breathing, actually “encourage” pathogens to penetrate deep into the tonsillar tissues where they are acted on by numerous lymphoid follicles and eliminated. This seems to be the major function of tonsils—to help children’s bodies recognize, destroy, and develop immunity to common environmental pathogens so that they will be protected in their later lives.

Tonsils are often removed in children who have recurrent throat infections, especially those involving the palatine tonsils on either side of the throat, whose swelling may interfere with their breathing and/or swallowing. See Figure 12.8[8] for an illustration of the tonsils.

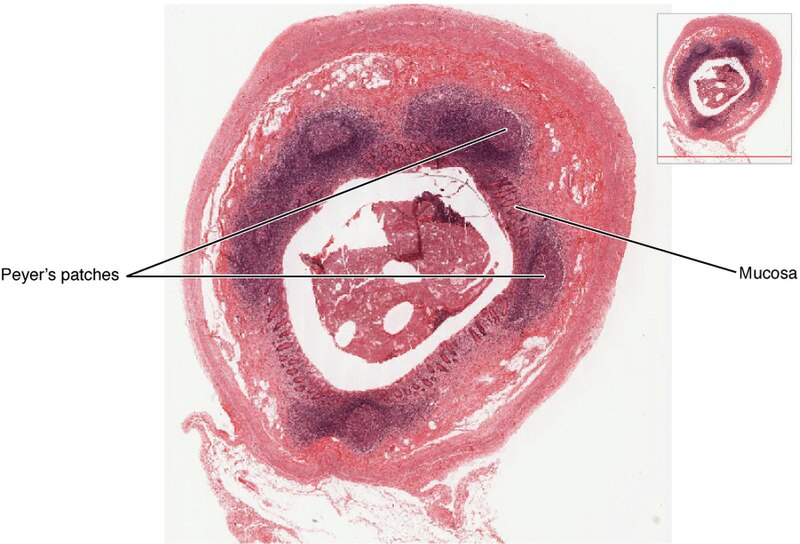

Mucosa-Associated Lymphoid Tissue

Mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) makes up dome-shaped structures found deep to the mucosa of the gastrointestinal tract, breast tissue, lungs, and eyes. Peyer’s patches, a type of MALT in the small intestine, are especially important for immune responses against ingested substances. Peyer’s patches contain specialized cells that sample material from the intestinal lumen and transport it to nearby follicles so that adaptive immune responses to potential pathogens can be mounted. A similar process occurs involving MALT in the mucosa and submucosa of the appendix. A blockage of the lumen triggers these cells to elicit an inflammatory response that can lead to appendicitis. See Figure 12.9[9] for an illustration of mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue.

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2022). Anatomy and physiology 2e. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “d3e44f4f487706f7c5de03874c905d6f42821321” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 4.0. Access for free at https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/21-1-anatomy-of-the-lymphatic-and-immune-systems ↵

- “2202_Lymphatic_Capillaries” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “2203_Lymphatic_Trunks_and_Ducts_System” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “2206_The_Location_Structure_and_Histology_of_the_Thymus” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “2207_Structure_and_Histology_of_a_Lymph_Node” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “2208_Spleen” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “2209_Location_and_Histology_of_Tonsils” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “2210_Mucosa_Associated_Lymphoid_Tissue_(MALT)_Nodule” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- Cancer Research UK. (2020, January 15). The lymphatic drainage system | Cancer Research UK [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cnsty5BAD9k ↵

- Alila Medical Media. (2018, November 20). The lymphatic system overview, animation [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=cCPyWFK0IKs ↵

Small, bean-shaped organs located throughout the lymphatic system, commonly found near the groin, armpits, neck, chest, and abdomen.

Small, thin-walled vessels that absorb interstitial fluid and transport lymph to larger lymphatic vessels.

Specialized lymphatic capillaries in the small intestine that absorb dietary fats and transport them as chyle.

A milky fluid consisting of dietary triglycerides combined with other lipids and proteins that enters lacteals during fat absorption.

Large vessels that drain lymph from specific regions of the body and empty it into one of two lymphatic ducts.

A two-lobed organ located between the sternum and heart that helps develop and mature T-cells, most active during childhood and shrinking after puberty.

A major secondary lymphoid organ.

Consist of a dense cluster of lymphocytes without a surrounding fibrous capsule.

Lymphoid nodules located along the inner surface of the pharynx (throat) and are important in developing immunity to oral pathogens.