10.5 Hemostasis

Hemostasis[1]

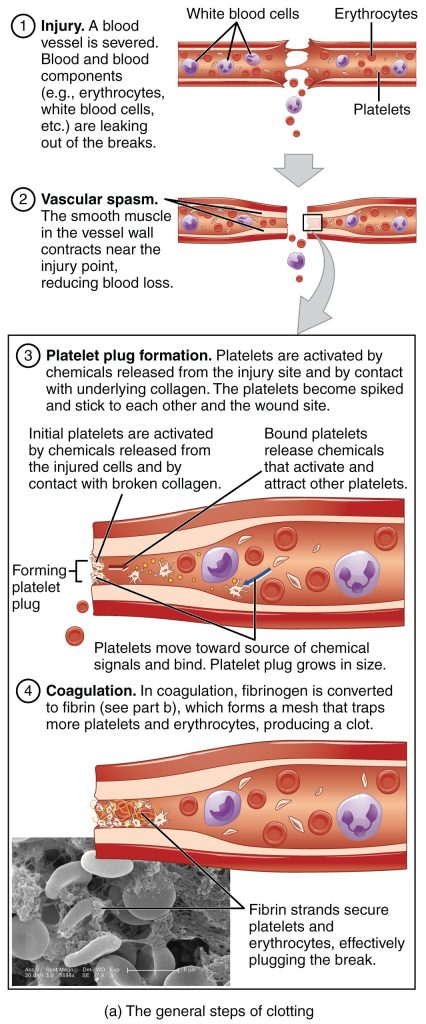

Although rupture of larger vessels usually requires medical intervention, hemostasis is very effective in dealing with small, simple wounds. There are three steps to the process: vascular spasm, the formation of a platelet plug, and coagulation (blood clotting). Failure of any of these steps will result in hemorrhage (excessive bleeding).

Vascular Spasm

When a vessel is damaged, vascular spasm occurs to reduce blood loss. In a vascular spasm, the smooth muscle in the walls of the vessel constricts dramatically. The vascular spasm response is believed to be caused by several chemicals and by pain receptors in response to vessel injury. It typically lasts for up to 30 minutes, although it can last for hours.

Formation of the Platelet Plug

In the second step, platelets, which normally float free in the plasma, are attracted to the damaged vessel by chemicals. Platelets become spiked and sticky, clump together, and bind to the damaged blood vessel wall. Platelets release chemicals that attract more platelets until a platelet plug is formed. This process is an example of positive feedback. A platelet plug can temporarily seal a small opening in a blood vessel until more durable repairs are made. The platelets also release chemicals that will stimulate coagulation, the next step.

Coagulation

The more durable repairs are collectively called coagulation, meaning the formation of a blood clot. This process is sometimes described as a cascade because a complex series of chronological chemical reactions happen, involving various proteins called clotting factors, where one step prompts the next. The result is a strong clot made up of a mesh of fibrin—an insoluble filamentous protein made from the plasma protein fibrinogen. Platelets and red blood cells are trapped within this fibrin mesh, much like fish would be caught in a net. See Figure 10.8[2] for a summary of the three steps of hemostasis. The stabilized clot is acted on by contractile proteins within the platelets. As these proteins contract, they pull on the fibrin threads, bringing the edges of the clot more tightly together, similar to what we do when tightening loose shoelaces. This process is called clot retraction.

Fibrinolysis

To restore normal blood flow as the vessel heals, the clot must eventually be removed. Fibrinolysis is the gradual breakdown of the clot. During this process, the inactive protein plasminogen is converted into the active plasmin, which gradually breaks down the fibrin of the clot.

Clinical Applications of Hemostasis

Antiplatelet Medications

Aspirin is very effective at inhibiting the aggregation (clumping) of platelets and is classified as an antiplatelet medication. Patients at risk for cardiovascular disease often take a low dose of aspirin every day to prevent the formation of clots. Aspirin is also routinely administered during a heart attack or stroke to reduce the formation of a clot.

Anticoagulants

An anticoagulant is any substance that prevents coagulation. For example, heparin is a short-acting anticoagulant released by the basophils and found on the surfaces of cells lining the blood vessels. A pharmaceutical form of injectable heparin is typically administered to patients diagnosed with blood clots to prevent the growth of the clot or formation of additional clots. It is also commonly given to patients after surgery to prevent clots from forming, such as deep vein thrombosis.

Warfarin is an oral anticoagulant that is also commonly used to prevent blood clots. For example, a patient with deep venous thrombosis (DVT) may be prescribed warfarin for several months after being discharged from the hospital to prevent the formation of additional life-threatening clots.

Thrombolytics

A class of drugs called thrombolytic agents can help break down an abnormal clot during medical emergencies such as a cerebrovascular accident (CVA), commonly known as a stroke, or a myocardial infarction, commonly called a heart attack. Tissue plasminogen activator (tPA) is an enzyme that catalyzes the conversion of plasminogen to plasmin, the primary enzyme that breaks down clots. It is released naturally by endothelial cells but is also used as a medication. For example, if tPA is administered to a patient within three hours of developing symptoms of a thrombotic CVA, brain damage can often be avoided or lessened. However, some strokes are caused by a hemorrhage, in which a thrombolytic agent is not appropriate, so it is vital to determine the cause of the stroke before beginning treatment.

- Betts, J. G., Young, K. A., Wise, J. A., Johnson, E., Poe, B., Kruse, D. H., Korol, O., Johnson, J. E., Womble, M., & DeSaix, P. (2022). Anatomy and physiology 2e. OpenStax. https://openstax.org/books/anatomy-and-physiology-2e/pages/1-introduction ↵

- “1909_Blood_Clotting” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

Excessive or uncontrolled bleeding.

A sudden constriction of the smooth muscle in the walls of a blood vessel that reduces blood flow to limit bleeding.

The process where platelets release chemicals that attract more platelets to help seal a damaged blood vessel.

The process of blood clotting.

An insoluble filamentous protein made from the plasma protein fibrinogen.

The gradual breakdown of a blood clot.

An active enzyme that gradually breaks down the fibrin mesh of a blood clot during the process of fibrinolysis.

A medication that effectively inhibits the clumping (aggregation) of platelets and is classified as an antiplatelet drug.

Any substance that prevents coagulation.

A medication that prevents blood clotting by inhibiting the formation of fibrin, used as an anticoagulant.

An anticoagulant medication that prevents blood clot formation by interfering with vitamin K-dependent clotting factors.

An enzyme that converts plasminogen into plasmin, which breaks down blood clots. It is used medically to treat strokes and heart attacks caused by clots.