6.6 Joints

Joints[1]

Joints (also called articulations or arthroses) are where two bones, bone and cartilage, or bone and teeth meet and connect together. The adult human body has 206 bones, and with the exception of the hyoid bone in the neck, each bone is connected to at least one other bone in the body.

Many joints allow for movement between the bones. At these joints, the articulating surfaces can move smoothly against each other. However, the bones of other joints may be joined to each other by connective tissue or cartilage. These joints are designed for stability and provide for little or no movement. Joint stability and movement are inversely related characteristics. Stable joints allow for little or no movement, whereas joints that provide the most movement between bones are the least stable. Additionally, in stable joints, the articulating surfaces are strongly connected to each other. Understanding the relationship between joint structure and function helps explain why particular types of joints are found in certain areas of the body. Consider the following examples:

- Most of the joints of the skull are held together by fibrous connective tissue that do not allow for movement between the bones. This lack of mobility is important because the skull bones serve to protect the brain. Other joints connected by fibrous connective tissue allow for very little movement, which provides stability and weight-bearing support for the body. For example, the tibia and fibula of the leg are tightly connected to give stability to the body when standing.

- In other joints, the bones are held together by cartilage, which permits limited movements between the bones. For example, the joints of the vertebral column allow for small movements between vertebrae.

- Joints that allow for greater ranges of motion have articulating surfaces that are not directly connected to each other. Instead, these surfaces are enclosed within a space filled with lubricating fluid, which allows the bones to move smoothly against each other. These joints provide greater mobility, but because the bones are free to move in relation to each other, the joint is less stable. Most of the joints between the bones of the appendicular skeleton are these freely moveable joints.

Classification of Joints

Joints are classified both functionally and structurally.

Functional Classification

Functional classification describes the degree of movement between the bones, ranging from immobile, freely mobile or immovable, slightly mobile, to freely moveable joints. The amount of movement in a particular joint is related to the functional requirements for that joint. Immobile or slightly moveable joints serve to protect internal organs, give stability to the body, and allow for limited body movement. In contrast, freely moveable joints allow for extensive movements of the body and limbs. There are three types of joints based on the amount of movement they allow: synarthrosis, amphiarthrosis, and diarthrosis that are discussed in more detail in the following sections.

Synarthrosis

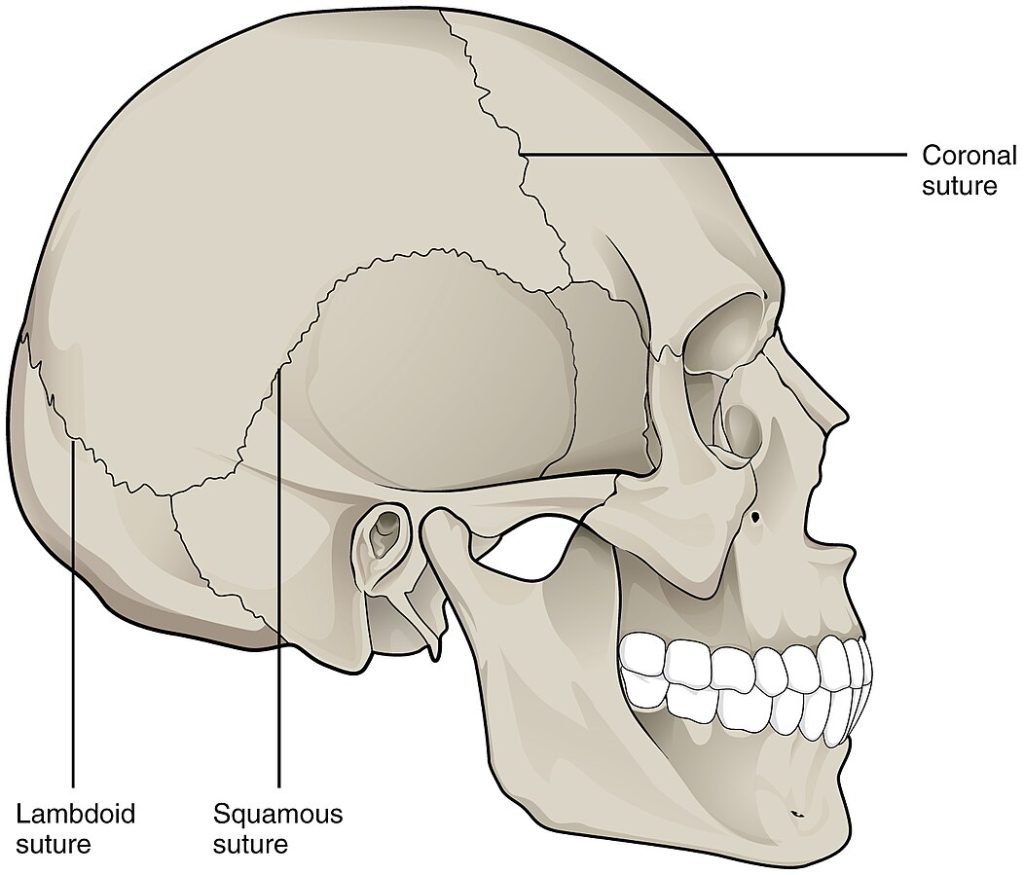

An immobile or nearly immobile joint is called a synarthrosis. Because they do not move, these joints provide for a strong connection between the articulating bones. This is important for locations where the bones provide protection for internal organs. An example of a synarthrosis is the skull sutures where the cranial bones meet. See Figure 6.46[2] for an illustration of the suture joints of the skull that are an example of a synarthrosis.

Amphiarthrosis

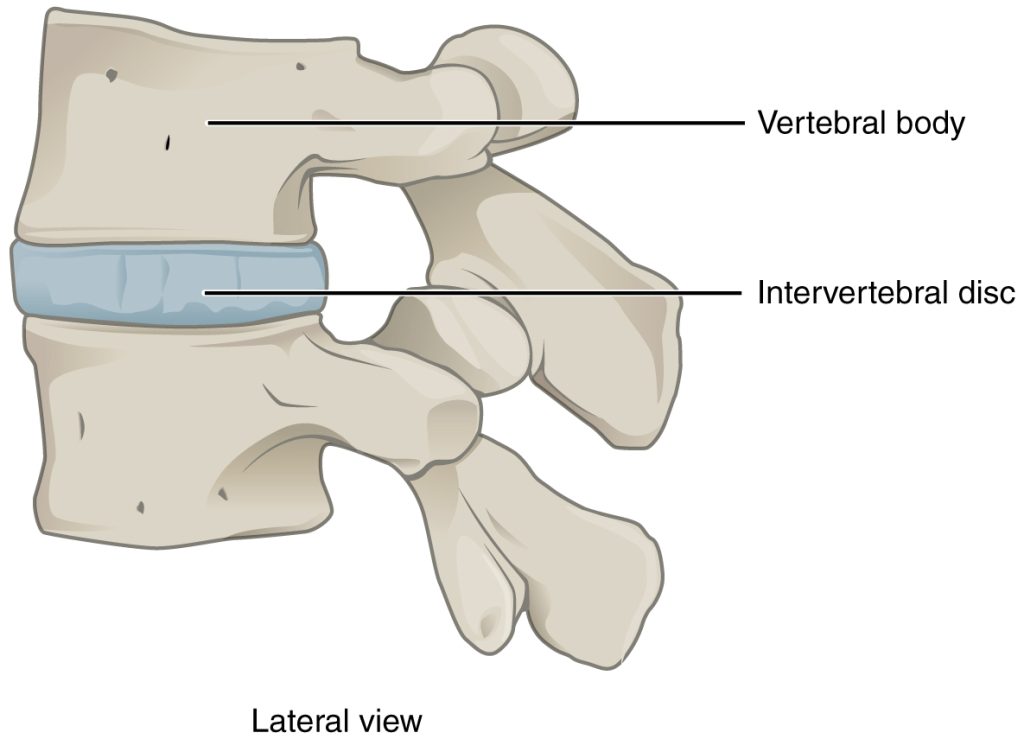

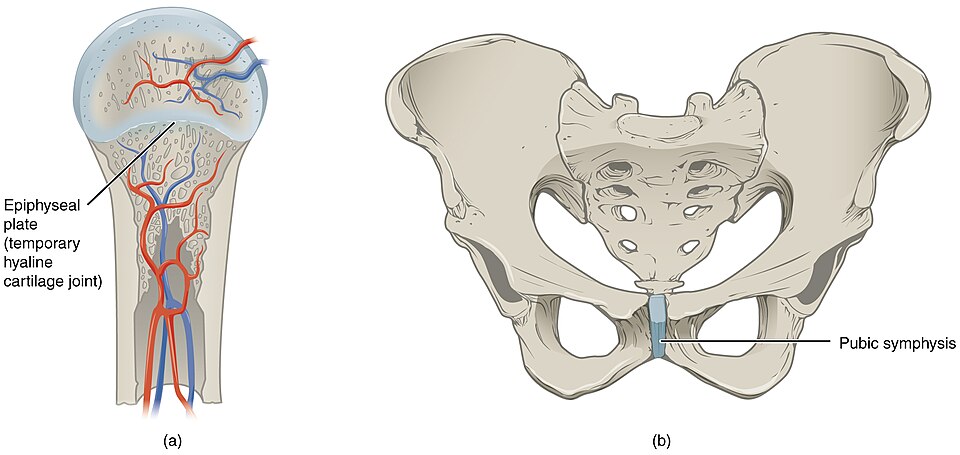

An amphiarthrosis is a joint that has limited mobility. An example of a joint that is an amphiarthrosis is the intervertebral disc, a thick pad of fibrocartilage located between two vertebrae. See Figure 6.47[3] for an illustration of an intervertebral disc. Intervertebral discs connect the vertebrae together but still allow for a small amount of movement between them. Another example of an amphiarthrosis is the pubic symphysis of the pelvis. The right and left pubic bones are strongly anchored to each other by fibrocartilage that holds the front of the pelvis together. This joint has very little mobility. The strength of the pubic symphysis is important for weight-bearing stability of the pelvis.

Diarthrosis

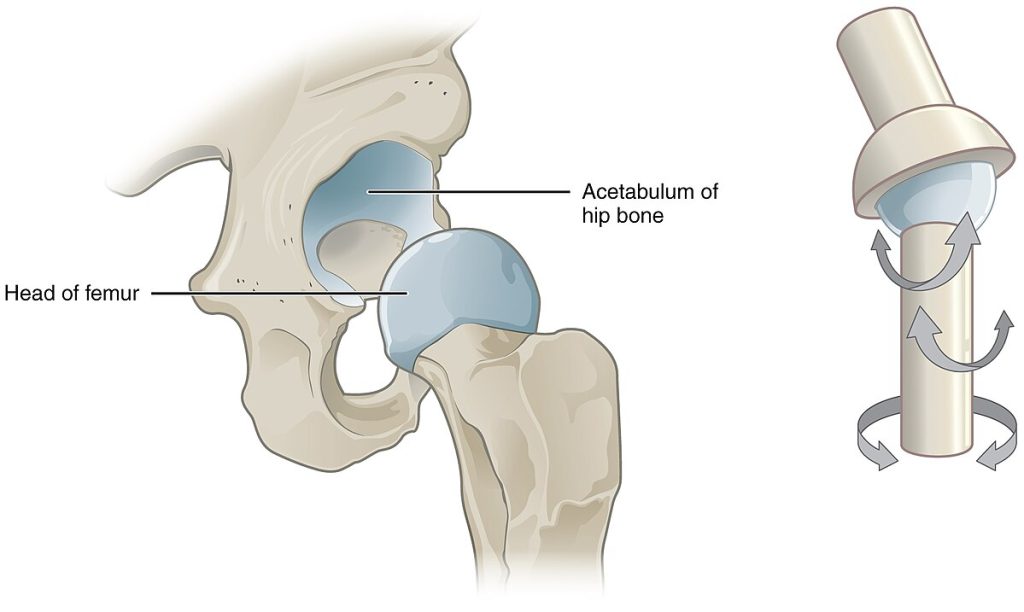

A freely mobile joint is classified as a diarthrosis. Diarthroses include all synovial joints of the body that provide the majority of body movements. Synovial joints are discussed in the following subsection. Most diarthrosis joints are found in the appendicular skeleton and give the limbs a wide range of motion. Diarthroses are divided into three categories, based on the number of axes of motion provided by each. An axis in anatomy is described as the movements in reference to the three anatomical planes: transverse, frontal, and sagittal. Thus, diarthroses are classified by their range of movement: uniaxial (for movement in one plane), biaxial (for movement in two planes), or multiaxial joints (for movement in all three anatomical planes). See Figure 6.48[4] for an illustration of the hip joint, an example of a multiaxial diarthrosis.

Structural Classification

Structural classification of joints considers how the bones are connected together. They may be connected with fibrous connective tissue, cartilage, or a fluid-filled space called a joint cavity. These differences divide the joints of the body into three different types: fibrous, cartilaginous, and synovial joints.

Fibrous Joint

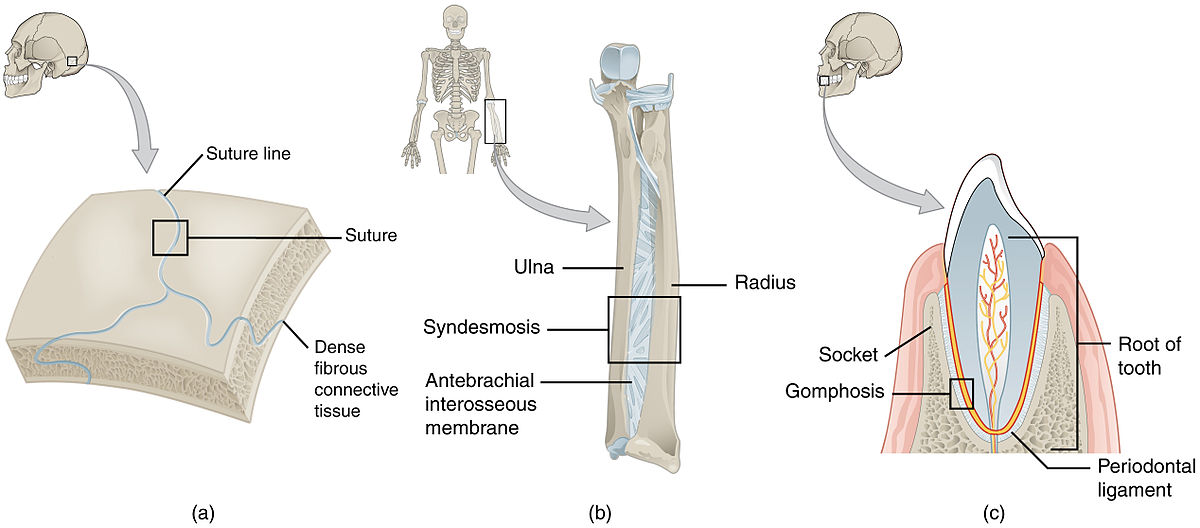

In a fibrous joint, bones are held together by fibrous connective tissue. Fibrous joints are also called synarthroses, fixed or non-movable joints. There are three types of fibrous joints: suture, gomphosis, and syndesmosis.

- Suture: A suture is a narrow fibrous joint found between most bones of the skull. Examples include the coronal suture, squamous suture, and lambdoid suture.

- Syndesmosis: A syndesmosis is a joint held together by a ligament, a type of connective tissue that connects bones together. A syndesmosis connects the radius and ulna of the lower arm together. Another example is the syndesmosis that joins the tibia and fibula of the lower leg.

- Gomphosis: A gomphosis is a narrow fibrous joint between the roots of a tooth and the bony socket in the jawbone into which the tooth fits.

See Figure 6.49[5] for an illustration of the types of fibrous joints.

Cartilaginous Joint

In a cartilaginous joint, bones are joined by cartilage, a tough but flexible type of connective tissue (either hyaline cartilage or fibrocartilage). Cartilaginous joints are also called amphiarthroses or slightly moveable joints. Examples of cartilaginous joints include the pubic symphysis and intervertebral discs. See Figure 6.50[6] for an illustration of cartilaginous joints.

Synovial Joint

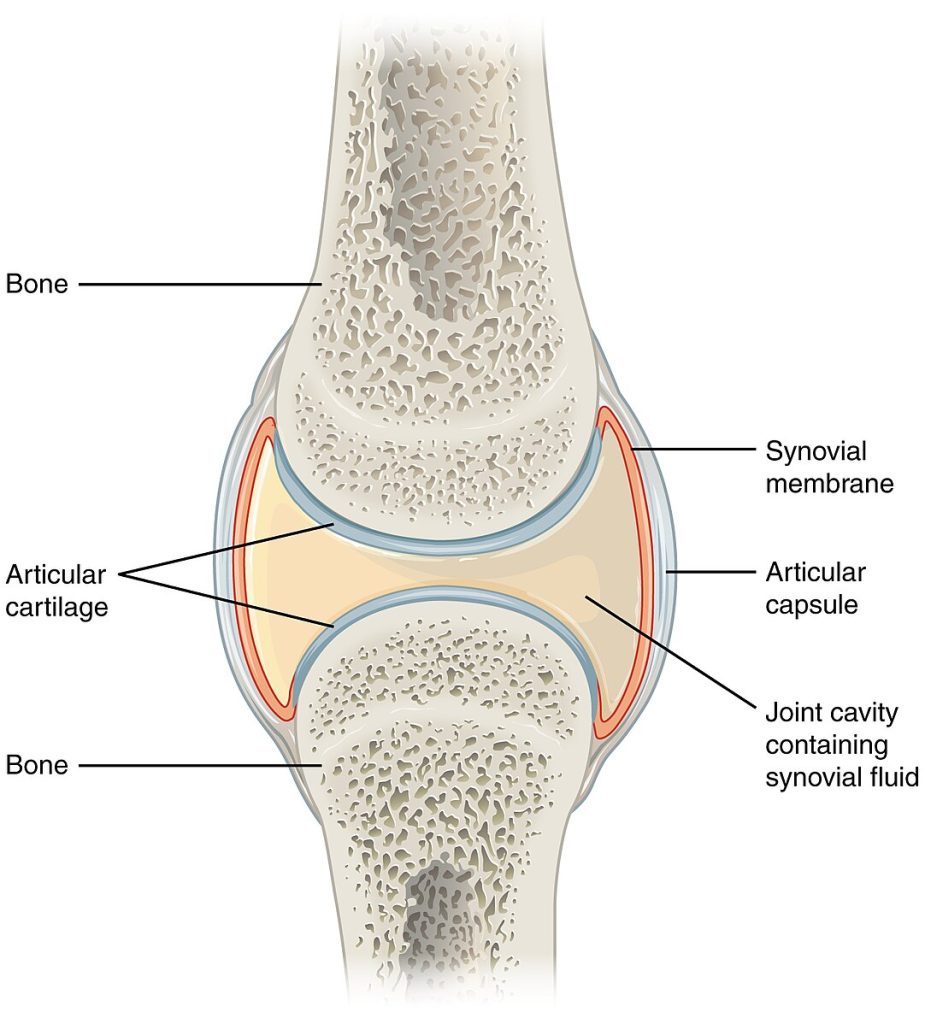

In a synovial joint, the bones are not directly connected but instead come together within a joint cavity filled with a lubricating fluid called synovial fluid. The joint cavity is enclosed by the articular or joint capsule. The articular capsule consists of an outer fibrous layer and an inner synovial membrane. The synovial membrane secretes synovial fluid, which is a thick, slippery fluid that provides lubrication to reduce friction between the bones of the joint. This fluid also acts as a shock absorber and provides nourishment to the articular cartilage that does not contain blood vessels. Friction between the bones at a synovial joint is also prevented by the presence of articular cartilage on the ends of the bones, allowing the articulating bones to move smoothly past each other without damaging the underlying bone tissue. Synovial joints allow for free movement between bones and are the most common joints of the body. See Figure 6.51[7] for an illustration of a synovial joint.

Outside of their articulating surfaces, bones are connected together by ligaments, which are strong bands of fibrous connective tissue. These strengthen and support the joint by anchoring the bones together and preventing their separation. Ligaments allow for normal movements at a joint, but limit the range of these motions, thus preventing excessive or abnormal joint movements.

Types of Synovial Joints

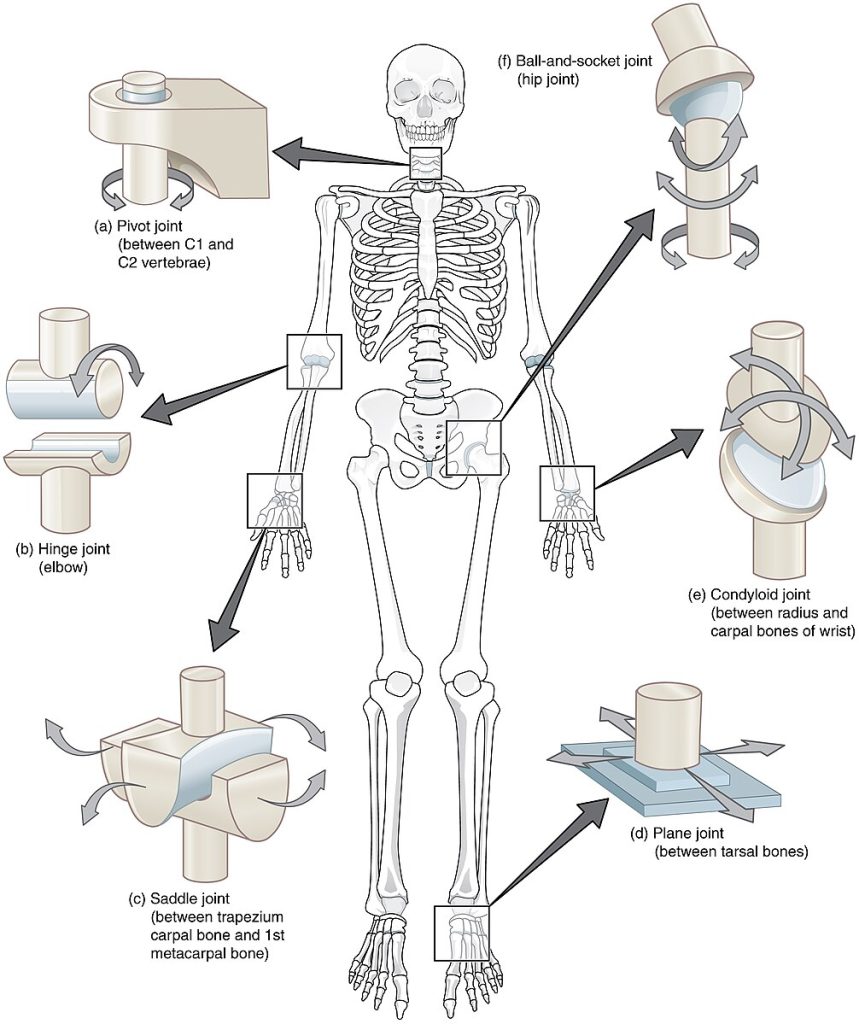

Synovial joints are subdivided based on the shapes of the articulating surfaces of the bones that form each joint. The six types of synovial joints are pivot, hinge, condyloid, saddle, plane, and ball-and socket joints:

- Ball and Socket: Synovial joint formed between the spherical end (ball) of one bone that fits into a cuplike depression (socket) of a second bone. The hip and shoulder joints are ball and socket joints.

- Hinge: Synovial joint formed by the convex surface of one bone meeting with the concave surface of a second bone. Hinge joints include the elbow, knee, and interphalangeal joints.

- Saddle: Synovial joint in which the ends of the bones have a saddle shape, which is concave in one direction and convex in the other. This allows the two bones to fit together like a rider sitting on a saddle. The joint at the base of the thumb is a saddle joint.

- Plane: Synovial joint formed between the flattened surfaces of two bones. The joints between the tarsals of the foot are an example of plane joints.

- Pivot: Synovial joint where the rounded portion of a bone rotates within a ring formed by a ligament and a bone. The joint between the atlas (C1) and the axis (C2) is an example of a pivot joint.

- Condyloid: Synovial joint formed by the shallow depression at the end of one bone receiving a rounded end from an adjacent bone or bones. They are found at the metacarpophalangeal joints of the fingers or the radiocarpal joint of the wrist. This joint is also known as an ellipsoid joint.

See 6.52[8] for an illustration of the different types of synovial joints.

Read more about movements at joints caused by the contraction of muscles in the “Skeletal Muscle” section of the “Muscular System” chapter.

View a supplementary YouTube video[9] demonstrating movement at synovial joints: Body Movement Terms Anatomy | Body Planes of Motion | Synovial Joint Movement Terminology.

Other Features of Synovial Joints

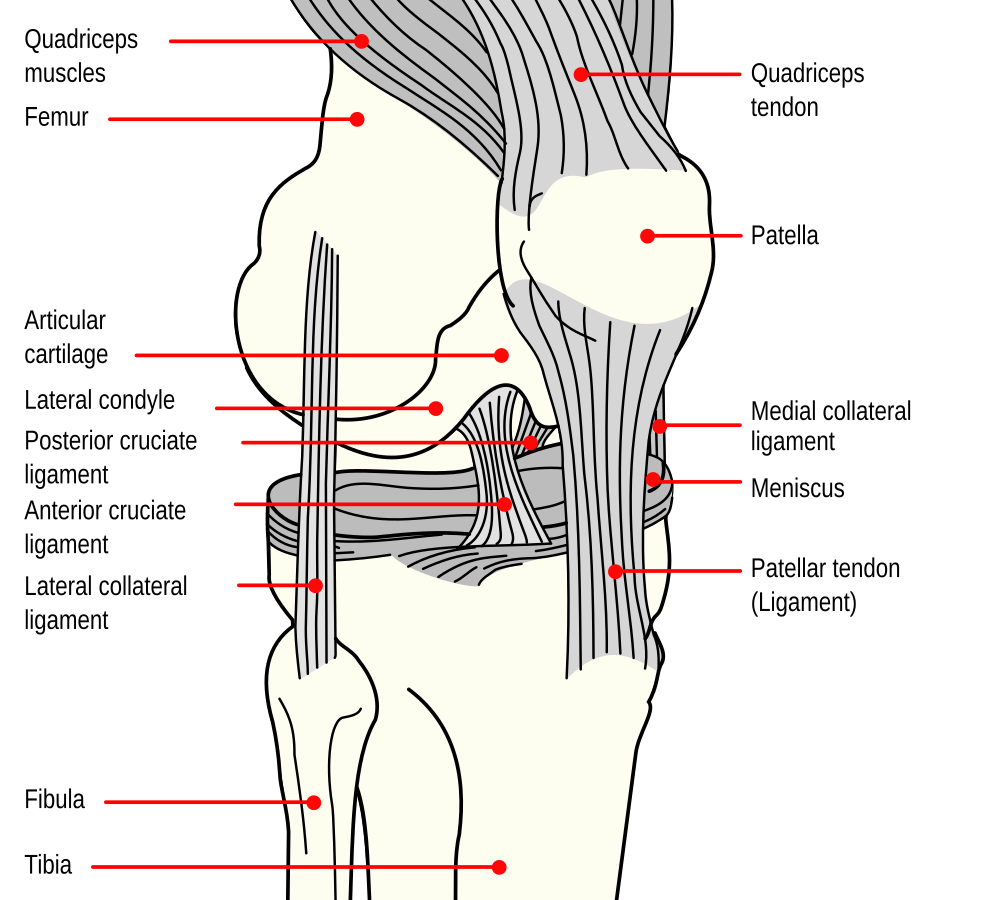

A few synovial disjoints of the body have a fibrocartilage structure located between the bones called an articular disc or meniscus. Articular discs are generally small and oval-shaped whereas a meniscus is larger and C-shaped. For example, the knee connects the femur (upper leg bone) to the tibia (one of the lower leg bones) with a meniscus and will be discussed in detail below.

In addition to the meniscus, the knee also contains ligaments, tendons, and additional cartilage. Ligaments in the knee include the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), lateral collateral ligament (LCL), medial collateral ligament (MCL), and posterior cruciate ligament (PCL). See Figure 6.53[10] for an illustration of these structures in the knee joint.

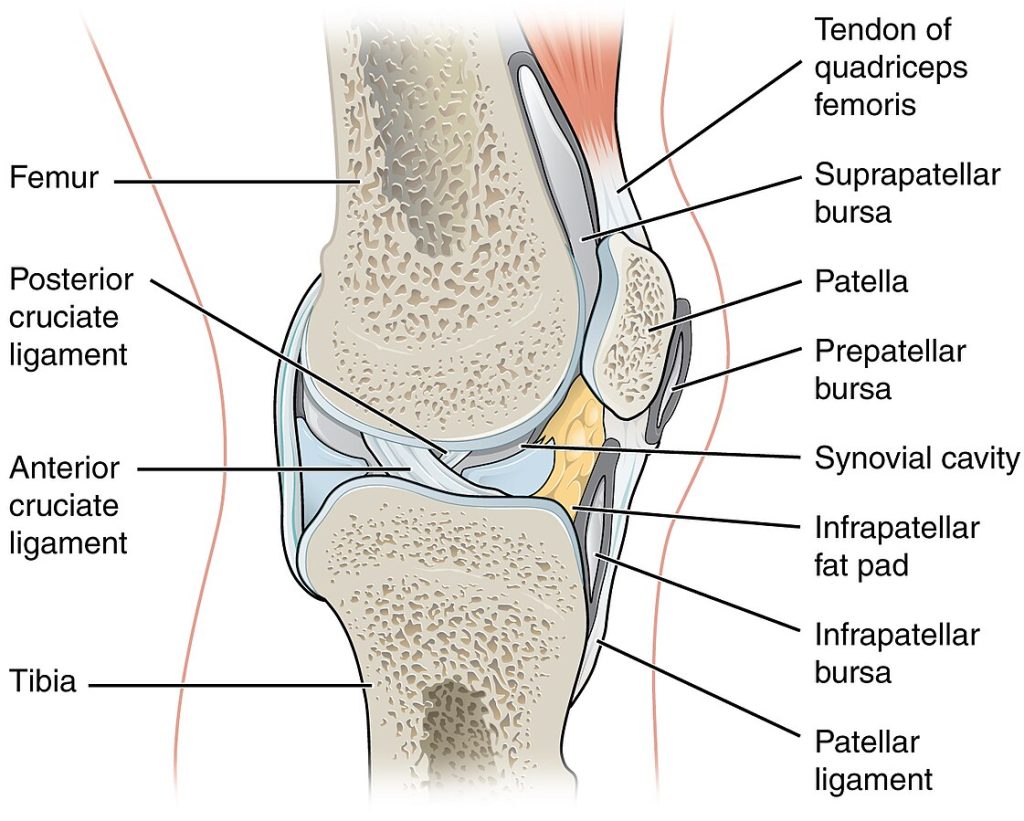

Another structure found superficial to a synovial joint is a bursa. A bursa is a thin connective tissue sac filled with fluid, and they are typically found in areas where skin, ligaments, muscles, or tendons rub against each other. Bursae are classified by their location. For example, a subcutaneous bursa is located between the skin and an underlying bone and allows skin to move smoothly over the bone. Examples of subcutaneous bursae are the suprapatellar bursa, prepatellar bursa, and infrapatellar bursa located in the knee, as seen in Figure 6.54.[11]

View a supplementary YouTube video[12] on joints: Joints: Crash Course Anatomy & Physiology #20.

- Ernstmeyer, K., & Christman, E. (Eds.). (2024). Medical terminology 2e. Open RN | WisTech Open. https://wtcs.pressbooks.pub/medterm/ ↵

- “901_Skull_Sutures” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “902_Intervertebral_disk-02” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “903_Multiaxial_Joint” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “904_Fibrous_Joints” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “906_Cartiliginous_Joints” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “907_Synovial_Joints” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- “909_Types_of_Synovial_Joints” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- RegisteredNurseRN. (2021, June 7). Body movement terms anatomy | Body planes of motion | Synovial joint movement terminology [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. Reused with permission. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=KO4nUzO7xoo ↵

- “Knee_diagram.svg” by Mysid is licensed in the Public Domain. ↵

- “908_Bursa.jpg” by OpenStax College is licensed under CC BY 3.0 ↵

- CrashCourse. (2015, May 26). Joints: Crash Course Anatomy & Physiology #20 [Video]. YouTube. All rights reserved. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=DLxYDoN634c ↵

Where two bones, bone and cartilage, or bone and teeth meet and connect together. Also known as articulations or arthroses.

The degree of movement between the bones, ranging from immobile, freely mobile or immovable, slightly mobile, to freely moveable joints.

An immobile or nearly immobile joint.

A joint that has limited mobility.

A freely mobile joint.

Classification which considers how the bones are connected together.

A fluid-filled space.

Bones held together by fibrous connective tissue.

A fixed (immobile) joint between bones of the skull.

A joint held together by a ligament, a type of connective tissue that connects bones together.

A narrow fibrous joint between the roots of a tooth and the bony socket in the jawbone into which the tooth fits.

Bones are joined by cartilage.

A strong, flexible connective tissue that protects your joints and bones.

The bones are not directly connected, but instead come together within a joint cavity filled with a lubricating fluid called synovial fluid.

Lubricating fluid within a joint cavity.

A type of connective tissue membrane that lines the cavity of a freely movable joint.

A thin layer of hyaline cartilage that reduces friction in joints and acts as a shock absorber.

Strong connective tissue bands that connect bones to other bones.

Synovial joint formed between the spherical end (ball) of one bone that fits into a cuplike depression (socket) of a second bone.

Synovial joint formed by the convex surface of one bone meeting with the concave surface of a second bone.

Synovial joint in which the ends of the bones have a saddle shape, which is concave in one direction and convex in the other.

An imaginary two-dimensional surface that passes through the body.

Synovial joint where the rounded portion of a bone rotates within a ring formed by a ligament and a bone.

Synovial joint formed by the shallow depression at the end of one bone receiving a rounded end from an adjacent bone or bones.

Small, oval-shaped fibrocartilage structure located between the bones.

Large C-shaped fibrocartilage located between the bones.

A key ligament within the knee joint that connects the thigh bone (femur) to the shin bone (tibia).

A band of tissue on the outside of the knee that connects the femur (thighbone) to the fibula (smaller lower leg bone).

A broad, thick ligament located on the inner side of the knee, connecting the thigh bone (femur) to the shin bone (tibia).

One of the four major ligaments in the knee joint, located at the back of the knee.

A thin connective tissue sac filled with fluid.